Battle of Fontenoy

The Battle of Fontenoy was a major engagement of the War of the Austrian Succession, fought on 11 May 1745, 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) outside Tournai, Belgium. A French army of 50,000 under Marshal Saxe defeated a Pragmatic Army [lower-alpha 1] of 52,000, led by the Duke of Cumberland. Along with his son the Dauphin, Louis XV of France was present and thus technically in command, a fact later used to bolster the regime's prestige.

| Battle of Fontenoy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Austrian Succession | |||||||

.jpg.webp) The Battle of Fontenoy by Pierre L'Enfant. Oil on canvas. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

50,000 men 110 guns |

52,000 men 101 guns | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 7,000 - 8,000 killed or wounded [1] |

10,000 - 12,000 killed, wounded or missing [2] 40 guns [3] | ||||||

At the end of 1744, the French were struggling to finance the war but held the initiative in the Austrian Netherlands. This offered the best opportunity for a decisive victory, and in late April 1745 they besieged Tournai. Its position on the upper Scheldt made it a vital link in the North European trading network, and Saxe knew the Allies would have to attempt its relief.

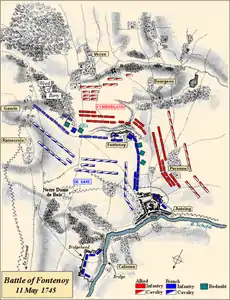

Leaving 22,000 men in front of Tournai, Saxe placed his main force in the villages of St Antoine, Vezin and Fontenoy, along a naturally strong feature which he strengthened with defensive works. After a number of unsuccessful flank assaults, the Allies attacked the French centre with an infantry column of 15,000 men. A series of cavalry charges and counterattacks by the Irish Brigade and Gardes Françaises, inflicted heavy casualties, and forced them to withdraw.

The Allies retreated toward Brussels, leaving the French in control of the battlefield; Tournai fell shortly afterwards, quickly followed by Ghent, Oudenarde, Bruges, and Dendermonde. In October, British troops were withdrawn to deal with the 1745 Jacobite Rising, facilitating the capture of Ostend and Nieuwpoort; by the end of 1745, France occupied much of the Austrian Netherlands, threatening British links with Europe. Saxe cemented his reputation as one of the most talented generals of the era, and restored French military superiority in Europe.

However, by December 1745, Louis XV's Finance Minister warned him France faced bankruptcy, leading to peace talks in May 1746 at the Congress of Breda. Despite victories at Rocoux in 1746, Lauffeld in 1747, and Maastricht in 1748, the cost of the war and the British naval blockade meant the French economic position continued to deteriorate. As a result, their gains in the Austrian Netherlands were returned after the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in November 1748.

Background

.jpg.webp)

The immediate cause of the War of the Austrian Succession was the death in 1740 of Emperor Charles VI, the last male Habsburg in the direct line. Since the Habsburg Monarchy[lower-alpha 2] was governed by Salic law, Maria Theresa, his eldest daughter and heir, was technically excluded from the throne, a condition waived by the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713.[4]

The closest male heir was Charles of Bavaria, who challenged the legality of Maria Theresa's succession. A family inheritance dispute became a European issue because the Monarchy dominated the Holy Roman Empire, a federation of mostly German states, headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. Technically an elected position, in January 1742 Charles became the first non-Habsburg Emperor in 300 years, supported by France, Prussia and Saxony. Maria Theresa was backed by the so-called Pragmatic Allies; Austria, Britain, Hanover, and the Dutch Republic.[5]

After four years of conflict, the main beneficiary was Prussia, which captured the Austrian province of Silesia during the First Silesian War (1740-1742). The richest province in the Empire, Silesian taxes provided 10% of total Imperial income and contained large mining, weaving and dyeing industries. Regaining it was a priority for Maria Theresa and led to the 1744–1745 Second Silesian War.[6]

Shortly after Charles died in January 1745, the Austrians over-ran Bavaria and on 15 April, defeated a Franco-Bavarian force at Pfaffenhofen. Charles' son, Maximilian III Joseph, now sued for peace and supported the election of Maria Theresa's husband, Francis Stephen, as the new Emperor. With Bavaria out of the war, Austria could focus on Silesia, while France was released from its involvement in Germany, and could concentrate on Italy and the Low Countries.[7]

The 1745 Campaign in the Austrian Netherlands

In the first half of 1744, France made significant advances in the Austrian Netherlands, before being forced to divert resources to meet threats elsewhere. Maurice de Saxe persuaded Louis XV this was the best place to inflict a decisive defeat on Britain, whose military and financial resources were central to the Allied war effort. His plan for 1745 was to bring the Pragmatic Army to battle on a ground of his choosing, before they could establish significant numerical superiority.[8]

France held a number of important advantages in the Austrian Netherlands, the most important being a unified command, in comparison to divisions among the Allies, who constantly quarrelled over strategy and objectives. Others included a highly competent commander in Saxe, and a marked superiority in numbers of troops available.[9]

Often referred to as Flanders, the area was a compact area 160 kilometres wide, the highest point only 100 metres above sea level, dominated by rivers running east to west. Until the advent of railways in the 19th century, commercial goods were largely transported by water and wars in this theatre were fought for control of major waterways, including the Lys, Sambre and Meuse.[10]

The most important was the River Scheldt (see Map), which began in Northern France and ran for 350-kilometre (220 mi) before entering the North Sea at Antwerp. Saxe planned to attack Tournai, a town close to the French border which controlled access to the upper Scheldt basin, making it a vital link in the trading network for Northern Europe.[11] It was also the strongest of the Barrier Forts, positions in the Austrian Netherlands held by the Dutch, with a garrison of 8,000; these factors meant the Allies would be compelled to fight for it.[12]

In March 1745, George Wade was replaced as Allied commander in Flanders by the 24-year-old Duke of Cumberland, advised by the experienced Earl Ligonier. In addition to British and Hanoverian troops, the Pragmatic Army included a large Dutch contingent, commanded by Prince Waldeck, with a small number of Austrians, led by Count Königsegg.[13] Cumberland's inexperience was magnified by his tendency to ignore advice, while as in previous years, the Allies were deeply divided. Flanders was not a military priority for Austria, Dutch commander Waldeck was unpopular with his subordinates, who often disputed his orders, while the British and Hanoverians resented and mistrusted each other.[14]

On 21 April, a French cavalry detachment under d'Estrées feinted towards Mons and Cumberland prepared to march to its relief.[15] Although it soon became clear this was a diversion, French intentions remained unclear until the siege of Tournai began on 28 April.[16] This uncertainty, combined with intelligence estimates that Saxe had only 30,000 men, meant the Allies failed to reinforce their field army with garrison troops, including 8,000 at Namur and Charleroi.[17]

Battle

After confirming the Allies were approaching from the south-east, Saxe left 22,000 men to continue the siege and placed his main force around the villages of Fontenoy and St Antoine, 8-kilometre (5.0 mi) from Tournai.[18] As Saxe considered his infantry inferior in training and discipline to their opponents, where possible he placed them behind defensive works or redoubts and fortified the villages.[19]

The main defensive line ran along the crest of a plateau, the right resting on the Scheldt, Fontenoy in the centre and the Bois de Barry on his left, supported by the Redoubt d'Eu, and the Redoubt de Chambonas. The ground in front of Fontenoy sloped down to the small hamlets of Vezon and Bourgeon (see Map). Known as the Chemin de Mons, this meant a direct attack on the French centre would be exposed to prolonged fire from in front and enfilade fire from the flanks.[20]

The Allies made contact with French outposts on the evening of 9 May, but a hasty reconnaissance by Cumberland and his staff failed to identify the Redoubt d'Eu. Next day, British and Hanoverian cavalry under James Campbell pushed the French out of Vezon and Bourgeon. Campbell's deputy, the Earl of Crawford, recommended infantry clear the Bois de Barry, while the cavalry swung around the wood to outflank the French left. Dutch hussars were sent to reconnoitre the route but withdrew when fired on by French troops in the wood, and the plan abandoned.[21]

The attack was postponed until the following day, both armies camping overnight on their positions.[22] At 4:00 am on 11 May, the Allies formed up, British and Hanoverians on the right and centre, Dutch on the left, with the Austrians in reserve. The Dutch were ordered to take Fontenoy and St Antoine, while a brigade under Richard Ingoldsby captured the Redoubt de Chambonas, and cleared the Bois de Barry. Once both flanks were engaged, massed Allied infantry in the centre under Ligonier would advance up the slope, and dislodge the main French army. As soon as it was light, the Allied artillery opened fire on the defences around Fontenoy, but the bombardment had little effect on the dug-in French infantry.[23]

Because Cumberland had badly under-estimated French numbers, he assumed their main force was in the centre and failed to appreciate the strength of the flanking positions. As Ingoldsby moved forward, he ran into the Redoubt d'Eu, and only then did the real strength of the French left become apparent. He requested artillery support, and the advance halted while his men skirmished with light troops in the woods, known as Harquebusiers de Grassins.[24] These numbered no more than 900 but uncertain of their strength, Ingoldsby hesitated; given the earlier failure to detect the redoubt, his caution was understandable but delayed the main attack.[25]

Growing impatient, at 7:00 am Cumberland ordered Ingoldsby to ignore the redoubt, and join the main column, although he failed to inform Ligonier of this change. As the Dutch advanced on Fontenoy, they came under heavy fire from French infantry in the nearby walled cemetery, and were repulsed with heavy losses. At 9:00 am, Ligonier sent an aide instructing Ingoldsby to attack the Redoubt d'Eu immediately; when Ingoldsby shared his new orders, Ligonier was apparently horrified.[27]

At 10:30, the Dutch attacked Fontenoy again, supported by the 42nd Foot; after some initial success, they were forced to retreat, and at 12:30 pm Cumberland ordered the central column to move forward.[28] This is generally agreed to have contained some 15,000 men, deployed in two lines.[d] Led by Cumberland and Ligonier, the infantry advanced up the slope, pausing at intervals to redress their lines and despite heavy casualties, retained formation as they reached the crest.[25]

Just before reaching the French position, the Allied column halted to check formation; having done so, the British Guards in the front rank allegedly invited the Gardes Françaises to fire first. The opening volley was so important commanders often preferred their opponents to fire first, particularly if they considered their troops better disciplined. [29] Thus goaded, the French fired prematurely, greatly reducing the impact of their first volley, while that of the British killed or wounded 700 to 800 men. The French front line broke up in confusion; many of their reserves had been transferred to meet the Dutch attack on Fontenoy, and the Allies now advanced into this gap.[30]

From their position near Notre Dame de Bois, Louis XV, his son the Dauphin, Noailles and Richelieu saw their forces fall back in disorder. Noailles implored Louis to seek safety, but Saxe assured him the battle was not lost; his deputy Löwendal ordered a series of cavalry attacks, which succeeded in forcing the Allies back.[31] With Cumberland isolated from the battle, no attempt was made to relieve pressure on Allied centre by ordering fresh attacks on Fontenoy, or the Redoubt d'Eu. Under fire from both flanks and in front, the column now formed a hollow, three sided square, reducing their firepower advantage.[32]

Although poorly co-ordinated, the French cavalry charges had allowed their infantry to reform; at 14:00, Saxe brought up his remaining artillery, which fired into the Allied square at close range. This was followed by a general assault, led by the Irish Brigade, who lost 656 men wounded or killed, including one-quarter of their officers, among them Colonel James Dillon of Dillon's Regiment.[33][lower-alpha 3]

Led by Saxe and Löwendahl, the Gardes Françaises attacked once more, while D'Estrées and Richelieu brought up the elite Maison du roi cavalry. The Allies were driven back with heavy losses; the 23rd Foot took 322 casualties, the three Guards regiments over 700.[35] Despite this, discipline and training allowed them to make a fighting withdrawal, the rearguard turning at intervals to fire on their pursuers.[36] Once they reached Vezon, the cavalry provided cover as they moved into columns of march, before retreating to Ath with little interference from the French.[1]

Aftermath

.PNG.webp)

Casualties at Fontenoy were the highest in western Europe since Malplaquet in 1709; the French lost around 7,000 or 8,000 killed and wounded, the Allies 10,000 to 12,000, including prisoners. Although later criticised for not following up, Saxe explained his troops were exhausted, while both the Allied cavalry and large parts of their infantry remained intact and fresh.[37] In great pain from edema or 'dropsy', he exercised command while being carried around the battlefield in a wicker chair.[38] These critics did not include Louis XV or Frederick the Great, who viewed Fontenoy as a tactical masterpiece and invited him to Sanssouci to discuss it.[39]

In contrast to Saxe, Cumberland performed poorly; he ignored advice from his more experienced subordinates, failed to follow through on clearing the Bois de Barry and gave Ingoldsby conflicting orders. Although praised for his courage, the inactivity of the Allied cavalry was partly due to his participation in the infantry attack, and loss of strategic oversight.[40] Ligonier and others viewed Fontenoy as a 'defeat snatched from the jaws of victory'; understandable for a 24 year old in his first major engagement, the same faults were apparent at the Battle of Lauffeld in 1747.[41]

Ingoldsby was court-martialled for the delay in attacking the Redoubt d'Eu, although his claim to have received inconsistent orders was clearly supported by the evidence. He was wounded, while two regiments from his brigade, the 12th Foot and Böselager's Hanoverian Foot, suffered the largest casualties of any units involved. The court concluded delay arose 'from an error of judgement, not want of courage', but he was forced out of the army, a decision many considered unjust.[42]

Victory meant France regained its position as the leading military power in Europe, while dispelling the myth of British military superiority established by Marlborough.[43] However, while their leadership was found lacking, the superior discipline of the Allied infantry showed that despite Saxe's efforts, his infantry still remained inferior to their best.[1] Since his presence at Fontenoy technically made him the senior commander, Louis became the first French king to win a battlefield victory over the English since Louis IX.[44] This was used to bolster his prestige, supported by a propaganda campaign which included a laudatory poem by Voltaire, titled La Bataille De Fontenoy.[45]

In the recriminations that followed, many English accounts blamed the Dutch for not relieving pressure on the centre by attacking Fontenoy.[46] This view was shared by Dutch cavalry commander Casimir van Schlippenbach, who criticised his infantry for refusing to advance. Although some Dutch cavalry units fled in panic, and their officers were later cashiered as a result, the infantry maintained formation and retreated in good order; most accounts agree the failure to advance was due to lack of leadership, and confusion caused by Cumberland himself.[47]

With no hope of relief, Tournai surrendered on 20 June, followed by the loss of Ostend and Nieuport; in October, the British were forced to divert resources to deal with the Jacobite rising of 1745, and Saxe continued his advance in 1746.[48] By the end of 1747, France controlled most of the Austrian Netherlands and threatened the Dutch Republic, but their economy was being strangled by the British naval blockade.[49]

Despite their presence in the Pragmatic Army, France did not declare war on the Dutch until 1747; doing so made their financial situation even worse, since as neutrals, the Dutch had been the main carriers of French imports and exports.[50] In 1748, France withdrew from the Netherlands, as agreed in the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle; returning the gains that cost so much, in exchange for so little, popularised a French phrase "as stupid as the Peace".[51]

Historian Reed Browning describes the effect of the French victory at Fontenoy thus: "The margin of victory had been narrow; the fruits thereof were nevertheless abundant."[1] Napoleon later declared Fontenoy prolonged the French Ancien Régime by 30 years.[52]

Notes

- Supporters of the 1713 Pragmatic Sanction were generally known as the Pragmatic Allies

- Often referred to as 'Austria', this included Austria, Hungary, Croatia, Bohemia, the Austrian Netherlands, and Parma

- "The encounter between the British and Irish Brigade was fierce, the fire constant, and the slaughter great; but the loss on the side of the British was such, they were at length compelled to retire".[34]

References

- Browning 1995, p. 212.

- Smollett 1848, p. 472.

- Townshend 2015, p. 69.

- Anderson 1995, p. 3.

- Black 1999, p. 82.

- Armour 2012, pp. 99-101.

- Browning 1995, pp. 203–204.

- McNally 2017, p. 6.

- Anderson 1995, p. 143.

- Childs 2013, pp. 32–33.

- White 1962, p. 149.

- Starkey 2003, p. 107.

- Townshend 2015, pp. 51–52.

- McNally 2017, pp. 12.

- Browning 1995, p. 207.

- Skrine 2018, p. 141.

- McNally 2017, pp. 14.

- Skrine 2018, pp. 151-152.

- Chandler 1990, p. 105.

- Charteris 2012, p. 174.

- Oliphant 2015, p. 50.

- Charteris 2012, p. 178.

- Skrine 2018, pp. 149–150, 158–159.

- Mcintyre 2016, p. 190.

- Skrine 2018, p. 160.

- MacKinnon 1883, p. 368.

- Oliphant 2015, p. 53.

- Skrine 2018, p. 168.

- Coakley & Stetson 1975, p. 7.

- Starkey 2003, p. 120.

- Browning 1995, p. 211.

- Chandler 1990, p. 126.

- McGarry 2014, p. 99.

- Townshend 2015, p. 66.

- Skrine 2018, pp. 182, 190.

- Black 1998, p. 67.

- White 1962, p. 163.

- Weigley 1991, p. 207.

- MacDonogh 1999, p. 206.

- Weigley 1991, p. 208.

- Oliphant 2015, p. 54.

- Skrine 2018, p. 233.

- Black 1999, p. 33.

- Starkey 2003, p. 109.

- Iverson 1999, pp. 207-228.

- Charteris 2012, pp. 178–179.

- McNally 2017, p. 46.

- Browning 1995, p. 219.

- McKay 1983, pp. 138–140.

- Scott 2015, p. 61.

- McLynn 2008, p. 1.

- Black 1999, p. 68.

Sources

- Anderson, M. S. (1995). The War of the Austrian Succession 1740–1748. Routledge. ISBN 978-0582059504.

- Armour, Ian (2012). A History of Eastern Europe 1740–1918. Bloomsbury Academic Press. ISBN 978-1849664882.

- Black, Jeremy (1998). Britain as a Military Power, 1688–1815. Routledge. ISBN 1-85728-772-X.

- Black, James (1999). From Louis XIV to Napoleon: The Fate of a Great Power. Routledge. ISBN 978-1857289343.

- Browning, Reed (1995). The War of the Austrian Succession. Griffin. ISBN 978-0312125615.

- Chandler, David G. (1990). The Art of Warfare in the Age of Marlborough. Spellmount. ISBN 0-946771-42-1.

- Charteris, Evan (2012) [1913]. William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland: His Early Life and Times (1721−1748) (repr. ed.). Forgotten Books.

- Childs, John (2013) [1991]. The Nine Years' War and the British Army, 1688−1697: The Operations in the Low Countries (2nd ed.). Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719089961.

- Coakley, Robert W; Stetson, Conn (1975). The War of the American Revolution. Center for Military History.

- Iverson, John R (1999). "Voltaire, Fontenoy, and the Crisis of Celebratory Verse". Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture. 28: 207–228. doi:10.1353/sec.2010.0146. S2CID 143582012.

- MacDonogh, Giles (1999). Frederick The Great. W & N. ISBN 978-0297817772.

- MacKinnon, Daniel (1883). Origins and Services of the Coldstream Guards, Volume I. Richard Bentley.

- McGarry, Stephen (2014). Irish Brigades Abroad: From the Wild Geese to the Napoleonic Wars. The History Press. ISBN 978-1-845887-995.

- Mcintyre, Jim (2016). The Development of British Light Infantry, Continental and North American Influences, 1740-1765. Winged Hussar. ISBN 978-0996365703.

- McKay, Derek (1983). The Rise of the Great Powers 1648–1815. Routledge. ISBN 978-0582485549.

- McLynn, Frank (2008). 1759: The Year Britain Became Master of the World. Vintage. ISBN 978-0099526391.

- McNally, Michael (2017). Fontenoy 1745: Cumberland's bloody defeat. Osprey. ISBN 978-1472816252.

- Oliphant, John (2015). John Forbes: Scotland, Flanders and the Seven Years' War, 1707–1759. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1472511188.

- Scott, Hamish (2015). The Birth of a Great Power System, 1740-1815. Routledge. ISBN 978-1138134232.

- Skrine, Francis Henry (2018) [1906]. Fontenoy and Great Britain's Share in the War of the Austrian Succession 1741–48 (repr. ed.). Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-0260413550.

- Smollett, Tobias (1848). History of England, from The Revolution to the Death of George the Second. II. London. OCLC 1019245095.

- Starkey, Armstrong (2003). War in the Age of Enlightenment 1700–1789. Praeger. ISBN 0-275-97240-2.

- Townshend, Charles Vere Ferrers (2015) [1901]. The military life of Field-Marshal George First Marquess Townshend 1724–1807. Books on Demand. ISBN 978-5519290968.

- Weigley, R.F (1991). Age of Battles: Quest for Decisive Warfare from Breitenfeld to Waterloo. Willey & Sons. ISBN 978-0253363800.

- White, J. E. M. (1962). Marshal of France: the Life and Times of Maurice, Comte De Saxe (1696–1750). Hmish Hamilton. OCLC 460730933.

Bibliography

- Geerdink-Schaftenaar, Marc (2018). For Orange and the States, part I: Infantry. Helion Publishing. ISBN 978-1911512158.

- Nimwegen, Olaf van (2010). The Dutch Army and the Military Revolutions, 1588–1688. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1843835752.

- Nimwegen, Olaf van (2002). De Republiek der Verenigde Nederlanden als grote mogendheid. De Bataafsche Leeuw. ISBN 978-9067075404.