Battle of Kesselsdorf

The Battle of Kesselsdorf was fought on 15 December 1745, between the Kingdom of Prussia and the combined forces of the Archduchy of Austria and the Electorate of Saxony during the part of the War of the Austrian Succession known as the Second Silesian War. The Prussians were led by Leopold I, Prince of Anhalt-Dessau, while the Austrians and Saxons were led by Field Marshal Rutowsky. The Prussians were victorious over the Royal Saxon Army and the Imperial Army of the Holy Roman Emperor.

| Battle of Kesselsdorf | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Silesian War (War of the Austrian Succession) | |||||||

Leopold von Dessau & Frederick Augustus Rutowsky | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

32,000[2] 33 field guns additional battalion guns |

35,000:

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

5,100:

|

10,500:

| ||||||

Preliminary maneuvers

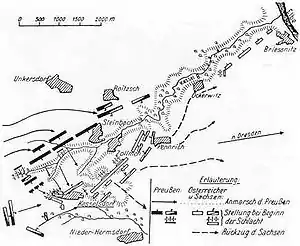

Two Prussian columns, one led by Frederick, the second by the Leopold the 'Old Dessauer' were converging on Dresden, the capital of Saxony, which was then an Austrian ally. Interposed between Leopold and Dresden was Rutowsky with an army of Saxons. Rapidly marching towards Dresden and Rutowsky was prince Charles who hoped to be able to reinforce both. Leopold moved slowly and deliberately forward entering Saxon territory on 29 November and advanced on Rutowsky at Leipzig, whereupon Rutowsky retired towards Dresden. By 12 December, Leopold reached Meissen and joined with a corps under Lehwaldt. Rutowsky was reinforced by some Austrians under Grünne and took up a position at Kesselsdorf, 5 miles west of Dresden, that covered Dresden while leaving him closer to the advancing Charles than Leopold was to Frederick. The Saxons deployed along a ridge that ran from Kesselsdorf to the river Elbe and that was fronted by a stream and marshy ground. The 7,000 Austrians under Grünne formed on the right near the Elbe. The line was long and there was a considerable gap in its center between the Saxons and the Austrians. On the fifteenth, Leopold finally came up. There was much snow and ice on the field.

Battle

The Prussians were slightly outnumbered 35,000 to 32,000. Additionally, the Saxons and Austrians had the advantage of the ground. Dessauer, a long experienced general now sixty eight years old, perceived that by taking the town of Kesselsdorf the enemies flank could be turned and concentrated his efforts against the Saxon portion of the army. The Saxons had the town defended with twenty-four heavy cannons,[4] their engineers and carpenters enhancing its defensibility. Leopold made dispositions for an attack by an elite force of infantry and grenadiers, however the ground was very difficult and the first attack was repulsed with considerable loss, including the officer leading the attack, General Hertzberg. A second, reinforced attack was made and this too failed with the Prussians fleeing in disorder. The Prussians had suffered some 1,500 casualties from the attacking forces of 3,500.

The Saxon grenadiers seeing the flight of the Prussians left their strong defensive position and made an impetuous pursuit of the Prussians which exposed them to a massed charge by the dragoons of the Prussian cavalry. The shock of the charge sent the Saxons tumbling back and through their former position in Kesselsdorf, driving them from the field. At this same time, Leopold's son, Prince Moritz, personally led an infantry regiment which broke through the Saxon center. The regiment, although isolated, held its ground while other Prussian regiments attempted but failed to link up with it due to the stubbornness of the Saxon defence. Eventually, Leopold's success in taking Kesselsdorf bore fruit and the Saxon flank was turned causing the Saxon line to collapse and their army to flee at nightfall.

The Prussians' losses amounted to over sixteen hundred killed and more than three thousand wounded, while the Saxon losses were less than four thousand killed and wounded with almost seven thousand Saxons taken prisoner as well as forty eight cannon and seven standards.[5] During the battle, the Austrians on the right never fired a shot, while Charles, who had reached Dresden and could hear the cannon, failed to march to the aid of his ally.

Aftermath

The Saxons fled in a wild panic into Dresden. There, despite the presence of Charles and his army of 18,000 and the Austrians' willingness to renew battle, they continued to flee. Leopold then linked up his forces with those of Frederick, who was so delighted by the victory that he embraced Leopold personally. The Saxons then abandoned Dresden, which Fredrick and Leopold occupied on the eighteenth after demanding its unconditional surrender. The Austrians subsequently began to negotiate the peace of Dresden immediately, ultimately ending the Second Silesian War and leaving Prussia's ally, France, to conduct the rest of the war of the Austrian Succession alone.

Notes

-

- "The Austrian imperial standard has, on a yellow ground, the black double-headed eagle, on the breast and wings of which are imposed shields bearing the arms of the provinces of the empire . The flag is bordered all round, the border being composed of equal-sided triangles with their apices alternately inwards and outwards, those with their apices pointing inwards being alternately yellow and white, the others alternately scarlet and black" (Chisholm 1911, p. 461)

- "The imperial banner was a golden yellow cloth...bearing a black eagle...The double-headed eagle was finally established by Sigismund as regent..." (Smith 1975, pp. 114–119)

- Tuttle 1888, p.42

- Cust 1862, p.74.

- Holcroft 1789, p. 278.

- Tuttle 1888, pp. 43-44.

References

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 454–463.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cust, Edward (1862). Annals of the wars of the eighteenth century. I. London.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Posthumous works of Frederic II. King of Prussia. 1. Translated by Holcroft, Thomas. London. 1789. p. 278.

- Smith, Whitney (1975). Flags through the ages and across the world. England: McGraw-Hill. pp. 114–119. ISBN 0-07-059093-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tuttle, Herbert (1888). History of Prussia. III. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Chandler, David (1990). The Art of Warfare in the Age of Marlborough. Spellmount. ISBN 0-946771-42-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Alexander Querengässer: Kesselsdorf 1745. Eine Entscheidungsschlacht im 18. Jahrhundert, Berlin 2020.