Battle of Hubbardton

The Battle of Hubbardton was an engagement in the Saratoga campaign of the American Revolutionary War fought in the village of Hubbardton, Vermont. Vermont was then a disputed territory sometimes called the New Hampshire Grants, claimed by New York, New Hampshire, and the newly organized and not yet recognized but de facto independent government of Vermont. On the morning of July 7, 1777, British forces, under General Simon Fraser, caught up with the American rear guard of the forces retreating after the withdrawal from Fort Ticonderoga. It was the only battle in Vermont during the revolution. (The Battle of Bennington was fought in what is now Walloomsac, New York.)

| Battle of Hubbardton | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

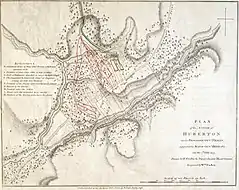

Detail of a 1780 map showing the area around Fort Ticonderoga | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Iroquois | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,000 men[3] | 1,030 men[4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

41-150 killed 96-457 wounded[5] 230 captured[6][7] |

49–60 killed[8][5] 141–168 wounded[8][5] | ||||||

The American retreat from Fort Ticonderoga began late on July 5 after British cannons were seen on top of high ground, Mount Defiance (a.k.a. Rattlesnake Mountain and Sugar Loaf Hill) that commanded the fort. The bulk of General Arthur St. Clair's army retreated through Hubbardton to Castleton, while the rear guard, commanded by Seth Warner, stopped at Hubbardton to rest and pick up stragglers.

General Fraser, alerted to the American withdrawal early on July 6, immediately set out in pursuit, leaving a message for General John Burgoyne to send reinforcements as quickly as possible. That night Fraser camped a few miles short of Hubbardton, and the German General Friedrich Adolf Riedesel, leading reinforcements, camped a few miles further back. Rising early in the morning, Fraser reached Hubbardton, where he surprised some elements of the American rear, while other elements managed to form defensive lines. In spirited battle, the Americans were driven back, but had almost succeeded in turning Fraser's left flank when Riedesel and his German reinforcements arrived, eventually scattering the American forces.

The battle took a large enough toll on the British forces that they did not further pursue the main American army. The many American prisoners were sent to Ticonderoga while most of the British troops made their way to Skenesboro to rejoin Burgoyne's army. Most of the scattered American remnants made their way to rejoin St. Clair's army on its way toward the Hudson River.

Background

General John Burgoyne began his 1777 campaign for control of the Hudson River valley by moving an army of 8,000 down Lake Champlain in late June, arriving near Fort Ticonderoga on July 1.[9] On July 5, General Arthur St. Clair's American forces defending Fort Ticonderoga and its supporting defenses discovered that Burgoyne's men had placed cannons on a position overlooking the fort. They evacuated the fort that night, with the majority of the army marching down a rough road (now referred to locally as the 1776 Hubbardton Military Road) toward Hubbardton in the disputed New Hampshire Grants territory.[10][11] The day was hot and sunny, and the pace was rapid and grueling; most of the army marched 30 miles (48 km) to Castleton before making camp on the evening of July 6.[12]

British troops give chase

The British general, a Scotsman named Simon Fraser discovered early on July 6 that the Americans had abandoned Ticonderoga. Leaving a message for General Burgoyne, he set out in pursuit with companies of grenadiers (9th, 29th, 34th, and 62nd Foot) and light infantry (24th, 29th, 34th, 53rd, and 62nd), as well as two companies of the 24th Regiment and about 100 Loyalists and Indian scouts.[13] Burgoyne ordered Riedesel to follow; he set out with a few companies of Brunswick jägers and grenadiers, leaving orders for the rest of his troops to come as rapidly as possible.[14] Fraser's advance corps was only a few miles behind Colonel Ebenezer Francis' 11th Massachusetts Regiment, which acted as St. Clair's rear guard.[14]

American general St. Clair paused at Hubbardton to give the main army's tired and hungry troops time to rest while he hoped the rear guard would arrive. When it did not arrive in time, he left Colonel Seth Warner and the Green Mountain Boys behind, along with the 2nd New Hampshire Regiment under Colonel Nathan Hale, at Hubbardton to wait for the rear while the main army marched on to Castleton.[15] When Francis' and Hale's men arrived, Warner decided, against St. Clair's orders, that they would spend the night there, rather than marching on to Castleton. Warner, who had experience in rear-guard actions while serving in the invasion of Quebec, arranged the camps in a defensive position on Monument Hill, and set patrols to guard the road to Ticonderoga.[16]

Baron Riedesel caught up with Fraser around 4 pm, and insisted that his men could not go further before making camp.[17] Fraser, who acquiesced to this as Riedesel was senior to him in the chain of command, pointed out that he was authorized to engage the enemy, and would be leaving his camp at 3 am the next morning. He then advanced until he found a site about three miles (4.8 km) from Hubbardton, where his troops camped for the night. Riedesel waited for the bulk of his men, about 1,500 strong, and also made camp.[18]

Attack

Fraser's men were up at 3 am, but did not make good time due to the darkness. Riedesel left his camp at 3 am with a picked group of men, and was still behind Fraser when the latter arrived at Hubbardton near dawn and very nearly surprised elements of Hale's regiment, which were scattered in the early fighting.[19] A messenger had arrived from General St. Clair delivering news that the British had reached Skenesboro, where the elements of the retreating army had planned to regroup, and that a more circuitous route to the Hudson River was now required. St. Clair's instructions were to follow him immediately to Rutland. Francis' men had formed a column to march out around 7:15 when the British vanguard began cresting the hill behind them.[20] Rapidly reforming into a line behind some cover, the Massachusetts men unleashed a withering volley of fire at the winded British.[21] General Fraser took stock of the situation, and decided to send a detachment around to flank the American left, at the risk of exposing his own left, which he hoped would hold until Riedesel arrived.[22] Riedesel reached the top of another hill, where he observed that the American line, now including parts of Hale's regiment, was in fact pressing on Fraser's left. He therefore sent his grenadiers to support Fraser's flank and directed the jägers against the American center.[23]

At some point early in the conflict, St. Clair was made aware of the gunfire off in the distance. He immediately dispatched Henry Brockholst Livingston and Isaac Dunn to send the militia camped closest to Hubbardton down the road in support of the action.[22] When they reached the area of those camps they found those militia companies in full retreat away from the gunfire in the distance, and no amount of persuasion could convince the men to turn around. Livingston and Dunn continued riding toward Hubbardton.[24]

Falling back to a secure position on Monument Hill, the Americans repulsed several vigorous British assaults, although Colonel Francis was hit in the arm by a shot.[24] He soldiered on, directing troops to a perceived weakness on Fraser's left. The tide of the battle turned when, after more than an hour of battle, Riedesel's grenadiers arrived. These disciplined forces entered the fray singing hymns to the accompaniment of a military band to make them appear more numerous than they actually were.[25] The American flanks were turned, and they were forced to make a desperate race across an open field to avoid being enveloped. Colonel Francis fell in a volley of musket fire as the troops raced away from the advancing British and scattered into the countryside.[26]

Aftermath

The scattered remnants of the American rear laboriously made their way toward Rutland in order to rejoin the main army. Harassed by Fraser's scouts and Indians, and without food or shelter, it took some of them five days to reach the army, which was by then nearing Fort Edward.[27] Others, including Colonel Hale and a detachment of 230 men, were captured by the British as they mopped up the scene.[28] Colonel Francis, in a sign of respect from his opponents, was buried with the Brunswick dead.[29]

Baron Riedesel and the Brunswickers departed for Skenesboro the next day, much to General Fraser's chagrin. Their departure left him in "the most disaffected part of America, every person a Spy", with 600 tired men, a sizable contingent of prisoners and wounded, and no significant supplies.[30] On July 9 he sent the 300 prisoners, under light guard but with threats of retaliation should they try to escape, toward Ticonderoga while he marched his exhausted forces toward Castleton and then Skenesboro.[6]

Livingston and Dunn, the two men sent toward the battle by St. Clair, were met by retreating Americans on the Castleton road after the battle was over. They returned to Castleton with the bad news, and the army marched off, eventually reaching the American camp at Fort Edward on July 12.[31][32]

Losses

The official casualty return for the British troops gives 39 British soldiers and 1 French-Canadian killed and 127 British and 2 French-Canadians wounded.[33] A separate return for the German troops has 10 killed and 14 wounded,[34] for a grand total of 50 killed and 143 wounded. Historian Richard M. Ketchum gives different British casualties of 60 killed and 168 wounded.[5] Ketchum gives American casualties as 41 killed, 96 wounded and 230 captured.[5][6] However, Lt. Anburey, present at the battle, states that the total dead and wounded of both sides found on the field in the aftermath amounted to 200 and 600 respectively. Subtracting the British-Canadian-German casualty returns from that gives American losses of 150 killed, 457 wounded and 230 captured.[28]

Hubbard Battlefield Historic Site

Hubbarton Battlefield Visitor Center | |

| |

| Location | 5696 Monument Hill Road Hubbardton, Vermont |

|---|---|

| Type | Visitor center |

| Owner | State of Vermont |

| Website | Hubbard Battlefield Historic Site |

A local body commissioned the erection of a monument on the battlefield site in 1859, and the state began acquiring battlefield lands in the 1930s for operation as a state historic site. The battlefield was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1971, and is the site of annual Revolutionary War reenactments.[4][35] The site's visitor center features a permanent exhibit which tells the story of the Battle of Hubbardton and places it in its context of the Revolutionary War. The Hubbardton Battlefield Trail features interpretive signs highlighting important points and locations of the battle.

In popular culture

The battle is used as the backdrop for the climax of the film Time Chasers. The battlefield is approximately 20 miles northwest of Rutland, Vermont, where most of the film's production was centered.

Notes

- Savas pg. 13

- Logusz pg. 129–30

- Anburey, pg.329

- Hubbardton Battlefield State Historic Site

- Ketchum (1997), p. 232

- Ketchum (1997), p. 215

- Anburey, pg.335

- Stanley, pp. 114–15

- Nickerson (1967), pp. 108,140

- Nickerson (1967), pp. 145–146

- At the time of this battle, the territory was claimed by both the state of New York and the Republic of Vermont, which declared its independence in January 1777, but did not actually adopt that name until July 8, the day after this action. Before that it was known as the Republic of New Connecticut.

- Nickerson (1967), pp. 147–148

- Morrissey (2000), p. 22

- Nickerson (1967), p. 147

- Ketchum (1997), p. 188

- Ketchum (1997), p. 190

- Ketchum (1997), p. 193

- Ketchum (1997), p. 194

- Ketchum (1997), pp. 194, 201

- Ketchum (1997), p. 198

- Ketchum (1997), p. 199

- Ketchum (1997), p. 200

- Ketchum (1997), p. 201

- Ketchum (1997), p. 203

- Nickerson (1967), pp. 151–153

- Ketchum (1997), p. 205

- Ketchum (1997), p. 209–210

- Anburey (1789) p. 336

- Ketchum (1997), p. 213

- Ketchum (1997), p. 214

- Nickerson (1967), p. 180

- Ketchum (1997), p. 216

- Stanley, p. 114

- Stanley, p. 115

- National Register Information System

References

- Anburey, Thomas (1923). Travels Through the Interior Parts of America 1776–1781, Volumes 1 and 2. Houghton Mifflin.

- Ketchum, Richard M (1997). Saratoga: Turning Point of America's Revolutionary War. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 978-0-8050-6123-9. OCLC 41397623. (Paperback ISBN 0-8050-6123-1)

- Logusz, Michael O. (2010). With Musket and Tomahawk: The Saratoga Campaign and the Wilderness War Of 1777. Casemate Publishers. ISBN 9781935149538.

- Morrissey, Brendan (2000). Saratoga 1777: Turning Point of a Revolution. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-862-4. OCLC 43419003.

- Nickerson, Hoffman (1967) [1928]. The Turning Point of the Revolution. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat. OCLC 549809.

- Savas, Theodore P. (2006). Guide to the Battles of the American Revolution. Casemate Publishers. ISBN 9781611210118.

- Pancake, John S (1977). 1777: The Year of the Hangman. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-5112-0. OCLC 2680804.

- Stanley, George F.G. (1961). For Want of a Horse: Being a Journal of the Campaigns against the Americans in 1776 and 1777 Conducted from Canada, By an Officer Who Served With Lt. Gen. Burgoyne. Sackville, New Brunswick: The Tribune Press Limited.

- "Hubbardton Battlefield State Historic Site". Vermont Division for Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on 12 October 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-17.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 24, 2008.