Battle of Ilipa

The Battle of Ilipa (/ˈɪlɪpə/) was an engagement considered by many as Scipio Africanus’s most brilliant victory in his military career during the Second Punic War in 206 BC.

| Battle of Ilipa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Punic War | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Roman Republic | Carthage | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Publius Cornelius Scipio |

Mago Barca Hasdrubal Gisco | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Polybius: 48,000 men • 45,000 infantry • 3,000 cavalry Livy: 55,000 men |

Polybius: 74,000 men • 70,000 infantry • 4,000 cavalry 32 war elephants Livy: 54,500 men • 50,000 infantry • 4,500 cavalry Unknown number of elephants | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 7,000 killed | 48,500 killed or captured | ||||||

Location within Spain | |||||||

It may have taken place on a plain east of Alcalá del Río, Seville, Spain, near the village of Esquivel, the site of the Carthaginian camp.[1]

Though it may not seem to be as original as Hannibal’s tactic at Cannae, Scipio's pre-battle maneuver and his reverse Cannae formation stands as the acme of his tactical ability, in which he forever broke the Carthaginian hold in Iberia, thus denying any further land invasion into Italy and cutting off a rich base for the Barca dynasty both in silver and manpower.

Prelude

After the Battle of Baecula and Hasdrubal Barca’s departure, further Carthaginian reinforcements were landed in Iberia in early 207 BC under Hanno, who soon joined Mago Barca. Together they were raising a powerful army by the heavy recruitment of Celtiberian mercenaries. Meanwhile, Hasdrubal Gisco also advanced his army from Gades into Andalusia. Thus Scipio was facing two concentrated enemy forces, one of which would no doubt fall on his rear if he tried to attack the other.

After careful planning, Scipio decided to send a detachment under Marcus Junius Silanus to strike Mago first. Marching with great speed, Silanus was able to achieve complete surprise when he fell on the Carthaginian camps, which resulted in the dispersion of Mago's Celtiberians and Hanno's capture.

Thus Hasdrubal was left alone in facing Scipio's concentrated force, but the Carthaginian general was able to avoid battle by splitting his troops among fortified cities. The Iberian campaign of 207 BC ended without any further major action.

Pre-battle maneuver

The next spring, the Carthaginians launched their last great effort to recover their Iberian holdings. Mago was joined at Ilipa by Hasdrubal Gisco, creating a force estimated at 54,000 to 74,000, considerably larger than Scipio's army of 48,000 men, which was composed of a large number of Spanish allies who were not as seasoned as Roman legionaries. Livy's figures, however, give the Carthaginian army 50,000 infantry and 4,500 cavalry (where he mentioned other sources give the figure of 70,000, such as Polybius at 11.20, but Livy believes it was the lesser number), whilst he puts Scipio's force at 55,000 men, so it was also possible Scipio outnumbered the Carthaginians by a slight margin.[2]

Upon the arrival of the Romans, Mago unleashed a daring attack on the Roman camp with most of his cavalry, under his Numidian ally Masinissa. However, this was foreseen by Scipio, who had concealed his own cavalry behind a hill, which charged into the Carthaginian flank, and threw back the enemy with heavy losses on Mago's side.

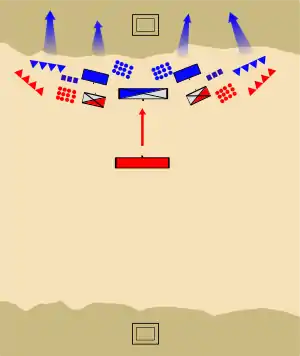

The two opponents spent the next few days observing and testing each other, with Scipio always waiting to lead out his troops only after the Carthaginians had advanced from their camp first. The Roman formation always presented the legions in the center and Iberians on the wings, thus leading Hasdrubal and Mago to believe that this would be the Roman arrangement on the day of battle.

Battle

Believing his deception had taken a firm hold on the Carthaginian commanders, Scipio made his move. First he ordered the army to be fed and armed before daylight. He then promptly sent his cavalry and light troops (velites) against the Carthaginian outposts at daybreak, while advancing with his main force behind, all the way to the front of the Carthaginian position. This day his legions stood at the wings and the Iberians in the centre.

Surprised by the Romans' sudden attacks, the Carthaginians rushed to arm themselves and sallied forth without breakfast. Still believing that Scipio would arrange his force in the earlier fashion, Hasdrubal deployed his elite Africans in the centre and the Spanish mercenaries on his wings; he was not able to change formation after discovering the new Roman arrangement because the opposing army was too close, as Scipio had ordered his troops to form for battle closer to the Carthaginian camp.

For the next few hours Scipio held back his infantry behind the skirmishing light troops and thus amplified the effect of the missed breakfast on his enemy. When he finally decided to attack, the light troops were called back through the space between the maniples to position themselves behind the legions on the wings; then the main advance began. With his wings advancing at a faster pace than the Iberians in his center, Scipio formed a concave, or reverse Cannae, battle line. Furthermore, the Roman general expanded his wings by ordering the light troops to the flanks of the legionaries, and the cavalry to the flank of the light troops, thus enveloping the whole Carthaginian line on both sides.

Still refusing his center, Scipio's legions, light troops, and cavalry attacked the half-trained Spaniards on the Carthaginian wings from front, flank, and rear respectively. The Carthaginian center was helpless to reinforce its wings with the threat of the Iberian force that was looming large in the near distance but not yet attacking.

With the inevitable destruction of its wings, the Carthaginian center was further demoralized and confused by the trampling by their own maddened elephants, which were being driven towards the center by the Roman cavalry attacking the flanks. Combined with hunger and fatigue, the Carthaginians started to withdraw, at first in good order. But as Scipio now pressed his advantage by ordering his Iberian center into battle, the Carthaginians crumbled, and a massacre that might have rivaled the one in Cannae was only averted by a sudden downpour, which brought a hold to all actions on the field, and enabled the remaining Carthaginians to seek refuge in their camp.

After-battle maneuvers

Although temporarily safe in their camp, the Carthaginians were not able to rest. Facing the inevitable Roman attack the next morning, they were obliged to strengthen their defenses. But, as more and more Spanish mercenaries deserted the Carthaginians as night drew forward, Hasdrubal tried to slip away with his remaining men in darkness.

Scipio immediately ordered a pursuit. Led by the cavalry, the whole Roman army was hot on Hasdrubal's tail. When the Romans finally caught up with the Carthaginian host, the butchery began. Hasdrubal was left with only 6,000 men, who then fled to a mountain top without any water supply. This remnant of the Carthaginian army surrendered a short time later, but not before Hasdrubal and Mago had made good their escape.

Aftermath

After the battle, Hasdrubal Gisco departed for Africa to visit the powerful Numidian king Syphax, in whose court he was met by Scipio, who was also courting the favor of the Numidians.

Mago Barca fled to the Balearics, whence he would sail to Liguria and attempt an invasion of northern Italy.

After his final subjugation of Carthaginian Iberia and revenge upon the Iberian chieftains, whose betrayal had led to the death of his father and uncle, Scipio returned to Rome. He was elected consul in 205 BC with a near-unanimous nomination, and after receiving the Senate's consent, he would have the control of Sicily as proconsul, from where his invasion of the Carthaginian homeland would be realized.

References

- "The Search for the Battle-site of Ilipa: Back to Basics". www.academia.edu. Retrieved 2016-04-09.

- Livy, 28.13

- Adrian Goldsworthy; In the Name of Rome - The Men Who Won the Roman Empire; 2003; ISBN 0-297-84666-3

- B.H. Liddell Hart; Scipio Africanus: greater than Napoleon; 1926; ISBN 0-306-80583-9

- Nigel Bagnall; The Punic Wars; 1990; ISBN 0-312-34214-4

- Polybius; The Rise of the Roman Empire; Trans. Ian Scott-Kilvert; 1979; ISBN 0-14-044362-2

- Serge Lancel; Hannibal; Trans. Antonia Nevill; 2000; ISBN 0-631-21848-3

- Santiago Posteguillo; Las Legiones Malditas; 2008; ISBN 978-84-666-3768-8