Battle of Rhone Crossing

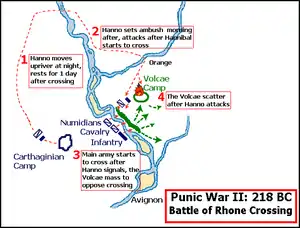

The Battle of the Rhône Crossing took place during the Second Punic War. The Carthaginian army under Hannibal Barca, while marching to Italy in the autumn of 218 BC, fought an army of the ethnically-Gaulish Volcae tribe on the east bank of the Rhone River. The pro-Roman Volcae, acting on behalf of a Roman army camped on the east bank near Massalia, intended to prevent the Carthaginians from crossing and invading Italy. Devising a plan to circumvent the Volcae, the Carthaginians, before crossing the river to attack the Gauls, had sent a detachment upriver under Hanno, son of Bomilcar, to cross at a different point and take position behind the Gauls. Hannibal led the main army across after Hanno sent smoke signals saying that the ambush was in place. As the Gauls massed to oppose Hannibal’s force, Hanno attacked them from behind and routed their army. Although the battle was not fought against a Roman army, the result of the battle had a profound effect on the war. Had the Carthaginians been prevented from crossing the Rhone, the 218 invasion of Italy might not have taken place. This is the first major battle that Hannibal fought outside the Iberian Peninsula.

| Battle of the Rhone Crossing | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Punic War | |||||||

Hannibal's army crossing the Rhone | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Carthage | Volcae, a tribe of Gauls | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Hannibal Barca | Unknown | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

38,000 infantry 8,000 cavalry 37 elephants | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

Background

Pre-war

.jpg.webp)

The First Punic War was fought between Carthage and Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC struggled for supremacy primarily on the Mediterranean island of Sicily and its surrounding waters, and also in North Africa.[1] The war lasted for 23 years, from 264 to 241 BC, until the Carthaginians were defeated.[2][3] The Treaty of Lutatius was signed by which Carthage evacuated Sicily and paid an indemnity of 3,200 talents[note 1] over ten years.[5] Four years later Rome seized Sardinia and Corsica on a cynical pretence and imposed a further 1,200 talent indemnity.[note 2][6][7] The seizure of Sardinia and Corsica by Rome and the additional indemnity fuelled resentment in Carthage.[8][9] Polybius considered this act of bad faith by the Romans to be the single greatest cause of war with Carthage breaking out again nineteen years later.[10]

Shortly after Rome's breach of the treaty the leading Carthaginian general Hamilcar Barca led many of his veterans on an expedition to expand Carthaginian holdings in south-east Iberia (modern Spain and Portugal); this was to become a quasi-monarchial, autonomous Barcid fiefdom.[11] Carthage gained silver mines, agricultural wealth, manpower, military facilities such as shipyards and territorial depth which encouraged it to stand up to future Roman demands.[12] Hamilcar ruled as a viceroy and was succeeded by his son-in-law, Hasdrubal, in the early 220s BC and then his son, Hannibal, in 221 BC.[13] In 226 BC the Ebro Treaty was agreed, specifying the Ebro River as the northern boundary of the Carthaginian sphere of influence.[14] A little later Rome made a separate treaty with the city of Saguntum, well south of the Ebro.[15] In 218 BC a Carthaginian army under Hannibal besieged, captured and sacked Saguntum.[16][17] In spring 219 BC Rome declared war on Carthage.[18] The Romans probably did not mobilize immediately after declaring war to aid Saguntum because of their preoccupation with the Second Illyrian War and Rome did not act hastily against Carthage.[19][note 3]

Roman Preparations

The Roman navy had been mobilized in 219 BC, fielding 220 quinqueremes for the Second Illyrian War.[23] It was the long-standing Roman procedure to elect two men each year, known as consuls, to each lead an army,[24] and Rome in 218 BC decided to raise two consular armies and strike simultaneously at Iberia and Africa.

Consul Tiberius Sempronius Longus received 4 legions (2 Romans and 2 allied, (consisting of 8,000 Roman and 16,000 allied infantry, 600 Roman and 1,800 allied horse) with instructions to sail for Africa escorted by 160 quinqueremes.[25] Publius Cornelius Scipio, the other consul, for 218 BC, received orders from the Senate to confront Hannibal in the theatre of the Ebro or the Pyrenees.[26][27][28][29][30] and received 4 legions (8,000 Roman and 14,000 allied infantry, 600 Roman and 1,600 allied horse)[31] and was to sail for Iberia escorted by 60 ships.[29][27] His brother Gnaeus accompanied him as a legate.

War in Cisalpine Gaul

The Boii and the Insubres, two major Gallic tribes in Cisalpine Gaul (modern northern Italy), antagonized by the founding of several Roman towns on traditionally Gallic territory, attacked the Roman colonies of Placentia and Cremona, causing the Romans to flee to Mutina, which the Gauls then besieged. Praetor L. Manlius Vulso marched from Ariminium with 600 Roman Horse, 10,000 allied infantry and 1,000 allied cavalry towards Cisalpine Gaul to aid the besieged Romans in the Summer of 218 BC.[32] This army was ambushed twice on the way, losing 1,200 men, and, although the siege of Mutina was raised, the army itself fell under a loose siege a few miles from Mutina at Tannetum.[33] The Roman Senate detached one Roman and one allied legion from the army of Scipio and sent it to the PO valley. The Scipio had to raise fresh troops to replace these and thus could not set out for Iberia until September.[34]

Punic preparations

Hannibal had dismissed his army to winter quarters after the Siege of Saguntum. When the army assembled in the summer of 218 BC, Hannibal stationed Hasdrubal Barca, his younger brother at the head of 12,650 infantry, 2,550 cavalry and 21 elephants (11,580 African foot, 300 Ligurains,500 Balearic slingers, 450 Liby-Phoenician[35] and mostly African cavalry)[36]to guard the Carthaginian possessions south of the Ebro.[37] and sent 20,000 mostly Iberian soldiers to Africa, including 13,850 foot, 1,200 horse and 870 Balearic slingers[38] and a contingent of 4,000 garrisoning Carthage itself.[39] Hannibal marched from Cartagena in May 90,000 foot and 12,000 cavalry, and 37 elephants. The elephants were reported by Appian; there is no mention of the elephants by Polybius or Livy, so it has been speculated that the elephants may have been carried to Emporiae by sea.[40][41] The Iberian contingent of the Punic navy, which numbered 50 quinqueremes (only 32 were manned) and 5 triremes, remained in Iberian waters, having shadowed Hannibal's army for some way.[42][43]

Campaigns in Northeast Spain

The Carthaginian Army crossed the Ebro River in three columns, the northernmost crossed at the confluence of the Ebro and Sicoris River and then proceeded along the river valley and into the mountain countries,[44] the central column crossed the Ebro at the oppidum of Mora and marched inland,[44] the main column under Hannibal, along with the treasure chest and elephants, crossed the Ebro at the town of Edeba,[45] and proceeded directly along the coast through Tarraco, Barcino, Gerunda, Emporiae and Illiberis.[44] The separate detachments marched in a way to provide mutual support if needed,[44] and the costal detachment under Hannibal was also tasked with countering any possible Roman intervention.[44]

Hannibal spent the months of July and August of 218 BC conquering the area north of the Ebro River, mainly confronting the Illergetes, the Bargusii, the Aeronosii, and the Andosini tribes.[46] Hannibal stormed a number of unspecified cities and this campaign aimed to subdue region as quickly as possible, leading to Carthaginian casualties.[47] After subduing the Iberian tribes, but leaving the Greek cities unmolested, Hannibal crossed over into Gaul to continue his march to Italy, leaving a certain Hanno with 10,000 infantry and 1,000 cavalry to garrison the newly conquered territory north of the Ebro, who had been identified various authors as Hannibal’s nephew[48] (son of Hasdrubal the Fair), a brother,[49] or no Barcid relation, who based himself to specifically watch over the Bargusii, whom he had reason to distrust due to their affiliation with the Romans. The Carthaginian army now consisted of 50,000 infantry and 9,000 cavalry as they crossed the Pyrenees Mountains into Gaul.[50] after Hannibal released 11,000 less reliable troops to return to their homes..[51] Hannibal had lost 22,000 soldiers, possibly to desertion of raw recruits[52] and heavy losses storming walled cities.[53]

Prelude

Hannibal had used diplomacy to pacify the Gallic tribes beyond the Pyrenees, and his march was not contested until they reached the territory of the Volcae on the banks of the Rhône by late September. By then, the army had shrunk to 38,000 foot and 8,000 horsemen. After reaching the west bank of the river, Hannibal decided to rest for three days. The Carthaginians collected boats and built rafts as they prepared to cross the river. Although the Volcae inhabited both banks of the river, they had retreated to the eastern where they encamped and awaited the Carthaginian crossing attempt.

Hannibal put Hanno, son of Bomilcar, in charge of a mobile column made up of infantry and cavalry on the third night, and sent this force upriver under cover of darkness to find another suitable crossing place. Led by local guides, Hanno located a crossing about 25 miles (40 km) to the north of the Carthaginian camp near an "island",[54] and crossed the river undetected. His Spanish fighters, which composed most of his forces probably on the account of being their best swimmers,[55] crossed the river with their shields over inflated animal skins, being followed by the rest of the detachment on hastily built rafts.[56] The force then rested for a day, and they then moved south on the following night (the second night after leaving the main army) and arrived behind the Volcae camp at dawn.

Opposing Armies

Carthaginian Army

The Carthaginian army at Rhone numbered 38,000 foot and 8,000 Horse, and a corps of 37 elephants. Carthage normally recruited mercenaries from various nations to augment a core of citizen soldiers and officers, Hannibal’s army was no exception, the uniting factor for the Carthaginian army was the personal tie each group had with Hannibal.[57][58] The cavalry arm contained at least 4,000 Numidian and 2,000 Iberians among the 8,000 troops, since these were the numbers had survived the crossing of the Alps to reach Italy. [59] The balance may have come from Numidians, Iberians, Celtiberians, Lusitanians, Gaetulians and Libyan-Phoenicians.

The Numidian cavalry were very lightly equipped, they rode short hardy ponies which was ridded bareback, wore no armor, carried javelins and a small hide bossless shields, and a short dagger or axe for close quarter combat.[60] The Gaetulian cavalry were equipped in similar fashion as the Numidians.[61] Although Numidian cavalry was outclassed by Roman Cavalry in close quarters fighting, they normally fought in loose groups and were excellent skirmishers.[62] The heavier Iberian cavalry may have included Celtiberans and Lusitanians along with other Spanish tribes among their numbers.[63] carried round shields, swords, javelins and thrusting spears. Along with iron or bronze helmets and short purple bordered tunics, some of the cavalry may have carried a small round shields, two javelins and a falcata, and wore no body armor, while others wore cuirasses, large oval shields and a thrusting spear along with swords, acting as genuine shock troops. [64][65] Celtiberian and Lusitanian horsemen wore mailshirts and carried small round shields along with javelins and slashing swords.[64]

When Hannibal reached Italy after crossing the Alps, he had 12,000 African and 8,000 Iberian infantry[59] along with 8,000 light troops,[66] so the 38,000 infantry present at the Rhone included these soldiers in their ranks as well. The Iberian contingent probably held Celtiberians and Lusitanians along with Iberians.[63] The African or Libyan infantry wore helmets and mail carried circular or oval shields with a metal boss, spears and swords, which were probably modeled after the Spanish falcata,[59] while the light infantry wore short sleeved tunics, carried javelins and a small round hide shield.[67] The light infantry was used for skirmishing while their heavier counterpart probably fought in a phalanx formation, or as swordsmen.[35]

The Iberian infantry fought with falcatas, wore no armor over their purple bordered dazzling white tunics, and carried large oval shields and a heavy javelin, and often wore a crested helmet made of animal sinews, while the light infantry carried a smaller shield and several javelins.[68] Celtiberians and Lusitanians used straight gladii,[64] as well as javelins and various types of spears.[60] Celtiberians wore black cloaks, carried wicker shields covered in hide or light shields similar to the Gauls used, wore sinew greaves and bronz, red crested helmets, while the Lusatanian skirmishers sinew helmets and linen cuirasses, aside from swords carried a small shield and several javelins.[64] Aside from the Numidian, Iberian, Libyan and Lusatinian light troops, Hannibal also had anauxiliary skirmisher contingent consisting of 1,000–2,000 Balearic slingers.[69] The Carthaginians also famously employed the war elephants which Hannibal had brought over the Alps; North Africa had indigenous African forest elephants at the time.[note 4][71][72] The sources are not clear as to whether they carried towers containing fighting men.[73]

The Gauls

The Gauls were brave, fierce warriors who fought in tribes and clans in massed infantry formation, but lacked the discipline of their Roman and Carthaginian opponents. The Infantry wore no armor, fought naked or stripped to the waist in plaid trousers and a loose cloak, a variety of metal bossed different size and shaped shields made of oak or linden covered with leather[74] and iron slashing swords.[75] Chieftains, Noblemen and their retainers made up the cavalry, wore helmets and mail, and used thrusting spears and swords.[74] Both Cavalry and Infantry carried spears and javelins for close quarter and ranged combat.[76]

The battle

Hanno signalled Hannibal by lighting a beacon and using smoke. The main Punic army started to cross the 1000 yard wide river. The rafts carrying Numidian cavalry were furthest upstream,[77] while boats carrying dismounted cavalry crossed below them, with three or four horses in tow, tied to their boats. These took the brunt of the river's current and the mobile infantry in canoes were placed below them. Some soldiers may have crossed the river by swimming. Hannibal himself was among the first to cross, and the rest of the Carthaginian army assembled on the western bank to cheer their comrades while they waited their turn to cross.

The Gauls, seeing the boats being launched, massed on the eastern riverbank to oppose the Carthaginians. Battle was soon joined on the eastern shore but the Carthaginians managed to establish a foothold. Hanno, timing his attack, sent part of his force to set the Volcae camp on fire while the rest of his force fell on the rear of the Gallic army just as Hannibal’s group established a foothold. Some of the Gauls then moved to defend the camp, while some immediately took flight. Soon the whole enemy force was scattered.

Aftermath

The majority of the Carthaginian army crossed the river on the day of the battle using rafts, boats and canoes in relays. Hannibal took measures to have his elephants ferried across the river the following day. Either the elephants were ferried across on rafts covered by dirt, or they swam across. Once the army had gathered on the eastern bank, scouting parties were sent out, as Hannibal had received word that a Roman fleet had reached Massalia. One group of Numidians met a group of Roman and Gallic cavalry while scouting and retreated after a brief skirmish.

Publius Scipio had sailed from Pisa and reached Massalia after sailing five days along the Ligurian coast, and there had disembarked his army. Learning from the locals that Hannibal had already crossed into Gaul, he sent 300 Roman horsemen and some Gallic mercenaries up the east bank of the Rhône to locate the Carthaginian army. These troops met and scattered the aforementioned force of Numidian cavalry out scouting for Hannibal, and managed to locate the Carthaginian camp as well.

Scipio, after learning Hannibal's location, loaded his heavy baggage onto the ships and marched north with his army to confront Hannibal. Despite outnumbering Scipio at this point, Hannibal decided to push towards the Alps and started marching north following the eastern bank of the Rhone. Scipio arrived at the deserted Carthaginian camp, and finding that the Carthaginians were three days' march away, returned to Massalia. He put his army under the command of his brother Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Calvus, then serving as his legate, and ordered him to sail for Iberia. Publius Scipio himself returned to Italy to organise the defences against Hannibal's anticipated invasion.

Battle site location

Historians disagree on the specific location of the battle site, identifying various locations starting from Bourg Saint-Andéol (De Beer, 1969, p. 122-3), Beaucaire[78] and Fourques on the Rhône, based on different hypotheses. Polybius (3.42.1) identified the battle site as being four days march from the sea. Assuming a 12–16 kilometres (7.5–9.9 mi) march limit per day for the Carthaginian army, the site is likely between Avignon and Orange, upstream of the Durance river, based on the probable ancient coastline, which has advanced further south because of silting from the Rhône since 218 BC.[79]

Hannibal’s vanishing soldiers

Hannibal might have mobilized 137,000 (Hannibal’s army: 102,000 troops, Hasdrubal's 15,000, army in Africa: 20,000)[80] soldiers before setting out for Italy. After subduing the lands north of Ebro in Catalonia, Hannibal left Hanno there with 11,000 soldiers, and released another 10,000 troops from service. Hannibal’s army numbered 59,000 soldiers when he crossed the Pyrenees. It seems that 22,000 soldiers had vanished since crossing the Ebro, without any information being available about their specific fate. On the Rhône, Hannibal had 46,000 soldiers available; another 13,000 had disappeared although the army had fought no battles between the Pyrenees and the Rhône. When the Carthaginian army finally reached Italy, it supposedly numbered 26,000 (Polybius 3.56.4). The Punic army had lost 75% of its starting strength during the journey to Italy. The cause of this drastic reduction is speculated as: large scale desertion by new recruits,[81] high casualties suffered north of the Ebro from direct assaults on walled towns,[82] garrisoning of parts of Gaul,[83] severe winter conditions faced on the Alps, and the unreliability of the figures given by Polybius.

Hans Delbruck proposed another hypothesis: Hannibal had mobilized a total of 82,000 troops, not 137,000. After leaving 26,000 in Iberia (with Hasdrubal Barca and Hanno), and releasing 10,000 prior to crossing the Pyrenees, he arrived in Italy with at least 34,000 soldiers.[84] The balance was lost in battles or to the Alpine elements. The basis of this theory is:

- Hannibal received no Iberian/African troops as reinforcements before 215 BC, when Bomilcar landed 4,000 Numidians at Lorci.

- At the Battle of Trebia, there is mention of 8,000 slingers and other light infantry of non Celtic/Gaulish or Italian origins.

Given that Hannibal had at least 6,000 cavalry, 20,000 heavy infantry and 8,000 light infantry before the Gauls joined him, a total of 34,000 troops when he reached Italy. Which means that the Carthaginian army had still lost 25% of its starting strength on the march to Italy.

Notes, citations and sources

Notes

- 3,200 talents was approximately 82,000 kg (81 long tons) of silver.[4]

- 1,200 talents was approximately 30,000 kg (30 long tons) of silver.[4]

- The Romans may have reasoned that if they raised an army (25,000 to 45,000 strong) and fleet and attacked Hannibal in Spain, they risked defeat as Hannibal was stronger in Spain. If they directly attacked Carthage, Hannibal would be able to leave part of his army to maintain the siege of Saguntum, cross over and defeat the Romans in Africa. If the Romans chose to strike simultaneously at Spain and Africa, Hannibal could still defeat the Roman armies in detail. Hannibal had mobilized at least 82,000 troops in 218 BC,[20] while the Romans in their two consular armies, had deployed a combined of 4 Roman and 4 allied legions, a total of 50,600 troops (Sempronius 24,000 foot and 2400 Horse, Scipio 22,000 foot and 2,200 Horse),[21] so Hannibal could engage the Romans over his familiar terrain with numerical superiority as well all his tactical genius.[22]

- These elephants were typically about 2.5 metres (8 ft) at the shoulder, and should not be confused with the larger African bush elephant.[70]

Citations

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 82.

- Lazenby 1996, p. 157.

- Bagnall 1999, p. 97.

- Lazenby 1996, p. 158.

- Miles 2011, p. 196.

- Scullard 2006, p. 569.

- Miles 2011, pp. 209, 212–213.

- Hoyos 2015, p. 211.

- Miles 2011, p. 213.

- Lazenby 1996, p. 175.

- Miles 2011, p. 220.

- Miles 2011, pp. 219–220, 225.

- Miles 2011, pp. 222, 225.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 143–144.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 144.

- Collins 1998, p. 13.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 144–145.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 145.

- Delbruck, Hans, Warfare in Antiquity, Volume 1, p 353 ISBN 0-8032-9199-X

- Delbruck, Hans, Warfare in Antiquity, Volume 1, p 353 ISBN 0-8032-9199-X

- Lazenby, J.F., Hannibal’s War, p 71 ISBN 0-8061-3004-0

- Delbruck, Hans, Warfare in Antiquity, Volume 1, p 353 ISBN 0-8032-9199-X

- Lazenby, J.F., Hannibal’s War, p 71 ISBN 0-8061-3004-0

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 50.

- Lazenby, J.F., Hannibal’s War, p 71 ISBN 0-8061-3004-0

- Dodge, Theodore (1994). Hannibal. Mechanicsburg, PA: Greenhill Books.

- Dodge 1994, p. 177

- Walbank, Polybius; transl. by Ian Scott-Kilvert; selected with an introduction by F.W. (1981). The rise of the Roman Empire (Reprint. ed.). Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-044362-2.

- Walbank 1979, p. 213

- Mommsen, Theodor (2009). The history of Rome (Digitally printed version ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-00974-4.

- Lazenby, J.F., Hannibal’s War, p 71 ISBN 0-8061-3004-0

- Goldsworthy, Adrian, The Fall of Carthage, p 151 ISBN 0-304-36642-0

- Goldsworthy, Adrian, The Fall of Carthage, p 151 ISBN 0-304-36642-0

- Zimmermann 2015, p. 283.

- Daly 2002, p. 90.

- Bath 1981, p. 42.

- Lazanby, John Francis, Hannibal's War, p32, ISBN 0-8061-3004-0

- Bath 1981, p. 41.

- Lazenby (1998) p. 32

- Lazenby (1998) p. 33, from Appian Hannibalic War 1.4.

- Peddie (2005) p. 18

- Dodge, Theodore A., Hannibal, p 172 ISBN 0-306-81362-9

- Peddie (2005) p. 14

- Dodge 1994, p. 173

- Dodge 1994, p. 172

- Dodge 1994, p. 171

- Walbank 1979, p. 211

- Bagnall, Nigel, The Punic Wars, p157, ISBN 0-312-34214-4

- Cottrell, Leonard, Hannibal: Enemy of Rome, p24, ISBN 0-306-80498-0

- Walbank 1979, p. 212

- Peddie, John, Hannibal's War, p 19 ISBN 0-7509-3797-1

- Goldsworthy (2003) pp. 159 & 167

- Bagnall (1990) p. 160

- Goldsworthy (2003) p. 160

- Ernle Bradford, Hannibal, Open Road Media, 2014

- Livy 21: 27

- Daly 2002, pp. 29–32.

- Daly 2002, pp. 81–112.

- Daly 2002, pp. 84.

- Goldsworthy 2001, p. 54.

- Daly 2002, pp. 99.

- Bath (1981) p.28

- Daly 2002, pp. 94.

- Daly 2002, pp. 100.

- Bath (1981) p.29

- Delbruck (1975) p.361

- Bath (1981) p.29

- Goldsworthy (2001) p.54

- Daly 2002, pp. 106.

- Miles 2011, p. 240.

- Bagnall 1999, p. 9.

- Lazenby 1996, p. 27.

- Sabin 1996, p. 70, n. 76.

- Daly 2002, pp. 103.

- Bath (1981) p.29

- Goldsworthy (2001) p.56

- Cottrell (1992) p. 44

- Lazenby (1998) p. 35

- Lancel (1999) p. 68

- Lazenby (1998) pp. 32-33

- Goldsworthy (2003) pp. 159 & 167

- Bagnall (1990) p. 160

- Lazenby (1998) p. 34

- Delbruck (1990) p. 364

Sources

- Bagnall, Nigel (1999). The Punic Wars: Rome, Carthage and the Struggle for the Mediterranean. London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-6608-4.

- Briscoe, John (2006). "The Second Punic War". In Astin, A. E.; Walbank, F. W.; Frederiksen, M. W.; Ogilvie, R. M. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History: Rome and the Mediterranean to 133 B.C. VIII. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 44–80. ISBN 978-0-521-23448-1.

- Champion, Craige B. (2015) [2011]. "Polybius and the Punic Wars". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 95–110. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Collins, Roger (1998). Spain: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285300-4.

- Curry, Andrew (2012). "The Weapon That Changed History". Archaeology. 65 (1): 32–37. JSTOR 41780760.

- Daly, Gregory (2002). Cannae: The Experience of Battle in the Second Punic War. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-26147-0.

- Edwell, Peter (2015) [2011]. "War Abroad: Spain, Sicily, Macedon, Africa". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 320–338. ISBN 978-1-119-02550-4.

- Erdkamp, Paul (2015) [2011]. "Manpower and Food Supply in the First and Second Punic Wars". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 58–76. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Fronda, Michael P. (2011). "Hannibal: Tactics, Strategy, and Geostrategy". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 242–259. ISBN 978-1-405-17600-2.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2006). The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265–146 BC. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-304-36642-2.

- Hau, Lisa (2016). Moral History from Herodotus to Diodorus Siculus. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-4744-1107-3.

- Hoyos, Dexter (2005). Hannibal's Dynasty :Power and Politics in the Western Mediterranean, 247-183 BC. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35958-0.

- Hoyos, Dexter (2015) [2011]. A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Hoyos, Dexter (2015b). Mastering the West: Rome and Carthage at War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-986010-4.

- Jones, Archer (1987). The Art of War in the Western World. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-01380-5.

- Koon, Sam (2015) [2011]. "Phalanx and Legion: the "Face" of Punic War Battle". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 77–94. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Lazenby, John (1996). The First Punic War: A Military History. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2673-3.

- Lazenby, John (1998). Hannibal's War: A Military History of the Second Punic War. Warminster: Aris & Phillips. ISBN 978-0-85668-080-9.

- Mahaney, W.C. (2008). Hannibal's Odyssey: Environmental Background to the Alpine Invasion of Italia. Piscataway, New Jersey: Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-59333-951-7.

- Miles, Richard (2011). Carthage Must be Destroyed. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-101809-6.

- Mineo, Bernard (2015) [2011]. "Principal Literary Sources for the Punic Wars (apart from Polybius)". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 111–128. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Rawlings, Louis (1996). "Celts, Spaniards, and Samnites: Warriors in a Soldiers' War". Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. Supplement (67): 8195. JSTOR 43767904.

- Sabin, Philip (1996). "The Mechanics of Battle in the Second Punic War". Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. Supplement. 67: 59–79. JSTOR 43767903.

- Scullard, Howard H. (2006) [1989]. "Carthage and Rome". In Walbank, F. W.; Astin, A. E.; Frederiksen, M. W. & Ogilvie, R. M. (eds.). Cambridge Ancient History: Volume 7, Part 2, 2nd Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 486–569. ISBN 978-0-521-23446-7.

- Shutt, Rowland (1938). "Polybius: A Sketch". Greece & Rome. 8 (22): 50–57. doi:10.1017/S001738350000588X. JSTOR 642112.

- Sidwell, Keith C.; Jones, Peter V. (1998). The World of Rome: an Introduction to Roman Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38600-5.

- Tipps, G.K. (1985). "The Battle of Ecnomus". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 34 (4): 432–465. JSTOR 4435938.

- Walbank, F.W. (1990). Polybius. 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06981-7.

- Zimmermann, Klaus (2015) [2011]. "Roman Strategy and Aims in the Second Punic War". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 280–298. ISBN 978-1-405-17600-2.

- Baker, G. P. (1999). Hannibal. Cooper Square Press. ISBN 0-8154-1005-0.

- Cottrell, Leonard (1992). Hannibal: Enemy of Rome. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80498-0.

- Peddie, John (2005). Hannibal's War. Sutton Publishing Limited. ISBN 0-7509-3797-1.

- Prevas, John (1998). Hannibal Crosses The Alps. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81070-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cottrell, Leonard (1992). Hannibal: Enemy of Rome. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80498-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Peddie, John (2005). Hannibal’s War. Sutton Publishing Limited. ISBN 0-7509-3797-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lancel, Serge, English Translator: Antonia Nevill (1998). Hannibal. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-21848-3.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2003). The Fall of Carthage. Cassel Military Paperbacks. ISBN 0-304-36642-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Miles, Richard (2011). Carthage Must Be Destroyed. Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-141-01809-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lazanby, John Francis (1978). Hannibal’s War. Aris & Phillips. ISBN 0-8061-3004-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bath, Tony (1981). Hannibal’s Campaigns. Barns & Nobles, New York. ISBN 0-88029-817-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goldsworthy, Adrian, (2007) (2007). Cannae Hannibal’s Greatest Victory. Phoenix, London. ISBN 978-0-7538-2259-3.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Delbruck, Hans (1975). Warfare in Antiquity Volume 1. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-9199-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dodge, Theodore Ayrault (1981). Hannibal. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81362-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |