Battle of McDowell

The Battle of McDowell, also known as the Battle of Sitlington's Hill, was fought on May 8, 1862, near McDowell, Virginia, as part of Confederate Major General Stonewall Jackson's 1862 Shenandoah Valley campaign during the American Civil War. After suffering a tactical defeat at the First Battle of Kernstown, Jackson withdrew to the southern Shenandoah Valley. Union forces commanded by Brigadier Generals Robert Milroy and Robert C. Schenck were advancing from what is now West Virginia towards the Shenandoah Valley. After being reinforced by troops commanded by Brigadier General Edward Johnson, Jackson advanced towards Milroy and Schenck's encampment at McDowell. Jackson quickly took the prominent heights of Sitlington's Hill, and Union attempts to recapture the hill failed. The Union forces retreated that night, and Jackson pursued, only to return to McDowell on 13 May. After McDowell, Jackson defeated Union forces at several other battles during his Valley campaign.

| Battle of McDowell | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Robert H. Milroy Robert C. Schenck |

Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson Edward Johnson | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 6,000[2]–6,500[3] | 6,000[3]–9,000[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 256–259 | c. 500–532 | ||||||

Background

In March 1862, Union forces commanded by Major General Nathaniel P. Banks moved into the Shenandoah Valley with the goal of supporting Major General George B. McClellan's advance up the Virginia Peninsula. Confederate resistance to Banks' advance consisted of a small army commanded by Major General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson. On March 21, the Union high command ordered the majority of Banks' command out of the Shenandoah Valley, leaving only a division commanded by Brigadier General James Shields to deal with Jackson. Shields left his camp at Strasburg and began moving north towards Winchester. On March 23, Jackson caught up with Shields' division near Kernstown. Faulty intelligence led Jackson to believe that only a small portion of Shields' force was at Kernstown, so he ordered an assault. Instead, Shields was in the area with his entire force, and a sharp battle was opened. The Confederates took a position behind a stone wall, but after Confederate Brigadier General Richard B. Garnett's brigade retreated after running low on ammunition, the flank of the Confederate position was exposed, forcing Jackson to withdraw from the field. Despite having defeated Jackson at Kernstown, Union high command was concerned by the aggressive behavior the Confederate army had shown, and began to send more troops to the Shenandoah Valley area, including the two divisions of Banks' army that had been moved out earlier.[4]

After the retreat from Kernstown, Jackson's force remained in the southern Shenandoah Valley awaiting orders and preparing for battle. In April, Jackson received orders to keep the Union forces in the Valley occupied with the goal of preventing them from joining McClellan's army near Richmond. Also coming to Jackson's camp were reinforcements commanded by Major General Richard Ewell.[5] Meanwhile, another Union force was moving against Jackson's army. Major General John C. Frémont's Mountain Department was moving towards Jackson from the west, across the Allegheny Mountains. Frémont's advance force consisted of 3,500 men commanded by Brigadier General Robert Milroy. Milroy reached the town of McDowell in early May, and was reinforced by another 2,500 men under Brigadier General Robert C. Schenck on 8 May.[6]

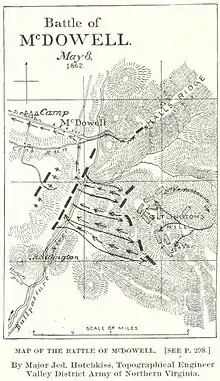

Jackson's columns departed their camps in the area of West View and Staunton, on the morning of 7 May. Jackson had been further reinforced by elements of Brigadier General Edward "Allegheny" Johnson's brigade.[7] The area around McDowell contained several points of high ground; a peak known as Jackson's Mountain was located west of the town, and Bull Pasture Mountain was east of McDowell. A road known as the Parkersburg and Staunton Turnpike ran roughly east to west through the area. A hill known as Sitlington's Hill was located south of the road, and Hull's Hill was north of the road. The Bull Pasture River ran between the town of McDowell and Sitlington's Hill and Hull's Hill. Expecting an attack, the Union commanders sent out small forces to serve as skirmishers. A portion of an artillery battery was also sent to the southern portion of Hull's Hill, where it kept up a regular fire despite not having a clear view of any Confederates. Union skirmishers from the 32nd Ohio Infantry, 73rd Ohio Infantry, and 3rd West Virginia Infantry made contact with the Confederate forces.[8]

Opposing forces

Union

Schenck had overall command of the Union force, although he still retained nominal command of his brigade. Milroy's brigade contained six regiments of infantry, two artillery batteries, and a regiment of cavalry. All of the units in Milroy's brigade were from the states of Ohio and West Virginia. Schenck's brigade consisted of three regiments of infantry, one battery of artillery, and a battalion of cavalry. Units from Ohio, West Virginia, and Connecticut were represented in Schenck's brigade.[9]

Confederate

The Confederate army consisted of the three brigades of Jackson's original force and the two brigades of Johnson's attached force. Jackson's original force contained a brigade of five regiments of infantry and two artillery batteries commanded by Brigadier General Charles S. Winder, a brigade of three infantry regiments, an infantry battalion, and two artillery batteries commanded by Colonel John A. Campbell, and a brigade of three infantry regiments and one artillery battery commanded by Brigadier General William B. Taliaferro. Johnson's force was composed of a brigade of three infantry regiments commanded by Colonel Zephaniah T. Conner and a second brigade of three infantry regiments commanded by Colonel William C. Scott. All of the units in the Confederate army were from Virginia, except for one Georgia regiment in Conner's brigade.[10]

Battle

Jackson then sent troops to take the lightly-defended crest of Sitlington's Hill. Scott's brigade led the way. The 52nd Virginia Infantry aligned in skirmishing formation on the Confederate left, and the 44th Virginia Infantry and 58th Virginia Infantry aligned between the 52nd Virginia and the road at the other end of Sitlington's Hill. The 12th Georgia Infantry of Conner's brigade supported the Virginians.[11] Jackson and Johnson moved to the top of the hill to have a point from which they could observe the Union position with the hopes of finding a path suitable for a flanking attack. However, Milroy ordered his Union troops to attack the Confederate position on Sitlington's Hill, disrupting the Confederate plans.[12] The rough terrain had led Jackson to decide against supporting his line on Sitlington's Hill with artillery.[3]

Milroy and Schenck decided to send five regiments against the Confederate line. The 25th Ohio Infantry and 75th Ohio Infantry (both from Milroy's brigade) aimed for where the Union commanders thought the center of the Confederate line was located. The 82nd Ohio Infantry of Schenck's brigade and 32nd Ohio Infantry of Milroy's brigade aligned to the right of the 25th and 75th Ohio, and the 3rd West Virginia Infantry advanced along the road on the Union left.[13] The fact that the Confederates held the high ground would prove to be a disadvantage for them: the sun was setting behind the Confederate line, silhouetting the soldiers against the sky. The hill also cast shadows that helped conceal the Union troops.[14] The 12th Georgia had been posted in an exposed position in front of the main Confederate line, and made first contact with the Union assault. The Georgians' position and outdated muskets gave them a decided disadvantage in the fighting. Further down the line, the 32nd and 82nd Ohio hit the main Confederate line, which had been reinforced by the 25th Virginia Infantry and the 31st Virginia Infantry of Conner's brigade.[15] The fighting became very heavy, with reports describing the battle as "fierce and sanguinary"[3] and "very terrific".[16] At one point, Confederates fighting against the 82nd Ohio attempted to use the bodies of dead soldiers as breastworks.[17]

The fifth Union regiment in the charge, the 3rd West Virginia, encountered skirmishers from the 52nd and 31st Virginia who were guarding the Confederate right flank. The Confederates then received further reinforcements from Campbell's and Taliaferro's brigades. The 10th Virginia Infantry of Taliaferro's brigade moved to the Confederate left, and Taliaferro's 23rd Virginia Infantry and 37th Virginia Infantry relieved the 25th Virginia in the main Confederate line. Towards the center of the Confederate line, the 12th Georgia, bloodied and out of ammunition, was forced to withdraw and was replaced by Campbell's 48th Virginia Infantry. Milroy shifted some of his regiments around, moving the 32nd Ohio to support the 75th Ohio near where the Georgians had been driven off, and bringing the 3rd West Virginia from the flank to the position formerly occupied by the 32nd Ohio. While the added weight of the 32nd Ohio forced the 48th Virginia to vacate its advanced position quickly, the outnumbered Union assailants broke off the assault. The fighting ended around 9:00 pm.[18]

Aftermath

Milroy and Schenck ordered a general retreat the night after the battle, after burning supplies they were unable to take on the retreat and disposing of extra ammunition by dumping it into the Bull Pasture River. Jackson began a pursuit of the Union column on 9 May, and the Union troops reached Franklin, West Virginia on 11 May. Jackson's pursuit reached as far as the vicinity of Franklin, but the Confederates broke off the retreat and fell back to McDowell on 13 May.[19]

Estimates of casualties vary between sources. One source places Confederate losses as 146 killed, 382 wounded, and four captured, for a total of 532; the same source gives Union losses as 26 killed, 230 wounded, and 3 missing, for a total of 259.[20] Others place losses as 256 for the Union and about 500 for the Confederates.[14][21] Of the Confederate losses, approximately 180 were suffered by the 12th Georgia alone.[14] Additionally, Confederate losses included Johnson, who had been shot in the ankle and severely wounded.[22]

Despite retreating from the field, some sources have argued that the Union forces achieved a draw by fighting Jackson to essentially a standstill. However, the defeat of the Union force and Milroy and Schenck's withdrawal from the Shenandoah Valley provided the Confederates with a strategic victory.[3] Jackson would later summarize the battle in the single sentence "God blessed our arms with victory at McDowell yesterday." Jackson continued his Valley campaign after McDowell. His next battle was against an outpost of Banks' army on 23 May, and the Confederates then defeated Banks' main force on 25 May. Further victories at the battles of Cross Keys on June 8 and Port Republic on June 9 restored Confederate control of the Shenandoah Valley.[23]

Battlefield preservation

The Civil War Trust (a division of the American Battlefield Trust) and its partners have acquired and preserved 583 acres (2.36 km2) of the battlefield as of 2019.[24] The battlefield is in a good state of preservation, with some of the wartime buildings still standing. A trail leads to the site of some of the fighting on Sitlington's Hill, and the site of the battle is commemorated with markers. Some of the soldiers killed during the battle are buried in a cemetery in McDowell.[25]

See also

Notes

- Kennedy 1998, p. 450.

- Kennedy 1998, p. 79.

- "McDowell (8 May 1862)". National Park Service. Archived from the original on October 28, 2004.

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 74–78.

- Davis 1988, pp. 173–174.

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 78–79.

- Cozzens 2008, pp. 260–261.

- Cozzens 2008, pp. 263–265.

- Cozzens 2008, p. 516.

- Cozzens 2008, p. 518.

- Cozzens 2008, pp. 265–266.

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 79–80.

- Cozzens 2008, pp. 266–267.

- Kennedy 1998, p. 80.

- Cozzens 2008, pp. 267–269.

- Tanner 1996, p. 191.

- Cozzens 2008, pp. 269–270.

- Cozzens 2008, pp. 270–272.

- Cozzens 2008, p. 274–275.

- Cozzens 2008, p. 273.

- Eicher 2001, p. 259.

- Cozzens 2008, p. 272.

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 80–87.

- "Saved Land 2019". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- "McDowell Battlefield". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

References

- Cozzens, Peter (2008). Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3200-4.

- Eicher, David J. (2001). The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Davis, Burke (1988). They Called Him Stonewall (reprint ed.). New York: Fairfax Press. ISBN 0-517-66204-3.

- Kennedy, Frances H. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). New York/Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Tanner, Robert G. (1996). Stonewall in the Valley: Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's Shenandoah Valley Campaign, Spring 1862. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0811720649.

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "NPS report on battlefield condition".

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "NPS report on battlefield condition".

External links

- Battle of McDowell in Encyclopedia Virginia

- The Battle of McDowell: Battle maps, history articles, photos, and preservation news (Civil War Trust)

- CWSAC Report Update