Shenandoah Valley

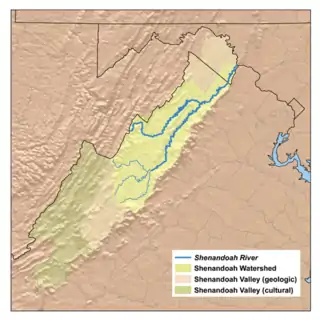

The Shenandoah Valley (/ˌʃɛnənˈdoʊə/) is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia in the United States. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians (excluding Massanutten Mountain), to the north by the Potomac River and to the south by the James River. The cultural region covers a larger area that includes all of the valley plus the Virginia highlands to the west, and the Roanoke Valley to the south. It is physiographically located within the Ridge and Valley province and is a portion of the Great Appalachian Valley.

| Shenandoah Valley | |

|---|---|

A view across the Shenandoah Valley | |

| Floor elevation | 500–1,500 feet (150–460 m) |

| Long-axis direction | Northeast to southwest |

| Geography | |

| Location | Virginia, Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia |

| Population centers | Winchester Harrisonburg Staunton Lexington Martinsburg, West Virginia |

| Borders on | Blue Ridge Mountains (east) Ridge and Valley Appalachians (west) Potomac River (north) James River (south) |

| Traversed by | |

Geography

Named for the river that stretches much of its length, the Shenandoah Valley encompasses eight counties in Virginia and two counties in West Virginia.

- Augusta County, Virginia

- Clarke County, Virginia

- Frederick County, Virginia

- Page County, Virginia

- Rockbridge County, Virginia

- Rockingham County, Virginia

- Shenandoah County, Virginia

- Warren County, Virginia

- Berkeley County, West Virginia

- Jefferson County, West Virginia

The antebellum composition included four additional counties that are now in West Virginia as well as four additional Virginia counties.[1]

- Morgan County, West Virginia

- Hampshire County, West Virginia

- Hardy County, West Virginia

- Pendleton County, West Virginia

- Botetourt County, Virginia

- Alleghany County, Virginia

- Bath County, Virginia

- Highland County, Virginia

The cultural region includes five more counties in Virginia:

Between the Roanoke Valley in the south and Harpers Ferry in the north, where the Shenandoah River joins the Potomac, the Valley cultural region contains 10 independent cities:

The central section of the Shenandoah Valley is split in half by the Massanutten Mountain range, with the smaller associated Page Valley lying to its east and the Fort Valley within the mountain range.

Notable caves

The Shenandoah Valley contains a number of geologically and historically significant limestone caves:

- Skyline Caverns

- Luray Caverns, designated a National Natural Landmark in 1974

- Shenandoah Caverns

- Endless Caverns

- Grand Caverns, designated a National Natural Landmark in 1973

- Dixie Caverns

Etymology

The word Shenandoah is of unknown Native American origin. It has been described as being derived from the Anglicization of Native American terms, resulting in words such as Gerando, Gerundo, Genantua, Shendo and Sherando. The meaning of these words is of some question. Schin-han-dowi, the "River Through the Spruces"; On-an-da-goa, the "River of High Mountains" or "Silver-Water"; and an Iroquois word for "Big Meadow", have all been proposed by Native American etymologists. The most popular, romanticized belief is that the name comes from a Native American expression for "Beautiful Daughter of the Stars".[2]

Another legend relates that the name is derived from the name of the Iroquoian chief Sherando (Sherando was also the name of his people), who fought against the Algonquian Chief Opechancanough, ruler of the Powhatan Confederacy (1618–1644). Opechancanough liked the interior country so much that he sent his son Sheewa-a-nee from the Tidewater with a large party to colonize the valley. Sheewa-a-nee drove Sherando back to his former territory near the Great Lakes. According to this account, descendants of Sheewanee's party became the Shawnee. According to tradition, another branch of Iroquoians, the Senedo, lived in present-day Shenandoah County. They were exterminated by "Southern Indians" (Catawba or Cherokee) before the arrival of white settlers.[3][4]

Another story dates to the American Revolutionary War. Throughout the war, Chief Skenandoa of the Oneida, an Iroquois nation based in New York, persuaded many of the tribe to side with the colonials against the British. Four Iroquois nations became British allies, and caused many fatalities and damage in the frontier settlements west of Albany. Skenandoa led 250 warriors against the British and Iroquois allies. According to Oneida oral tradition, during the harsh winter of 1777–1778 at Valley Forge, where the colonials suffered, Chief Skenando provided aid to the soldiers. The Oneida delivered bushels of dry corn to the troops to help them survive. Polly Cooper, an Oneida woman, stayed some time with the troops to teach them how to cook the corn properly and care for the sick. General Washington gave her a shawl in thanks, which is displayed at Shako:wi, the museum of the Oneida Nation near Syracuse, New York. Many Oneida believe that after the war, George Washington named the Shenandoah River and valley after his ally.[5][6]

History

First European explorers

Despite the valley's potential for productive farmland, colonial settlement from the east was long delayed by the barrier of the Blue Ridge Mountains. These were crossed by explorers John Lederer at Manassas Gap in 1671, Batts and Fallam the same year, and Cadwallader Jones in 1682. The Swiss Franz Ludwig Michel and Christoph von Graffenried explored and mapped the Valley in 1706 and 1712, respectively. Von Graffenried reported that the Indians of Senantona (Shenandoah) had been alarmed by news of the recent Tuscarora War in North Carolina.

18th century

Governor Alexander Spotswood's legendary Knights of the Golden Horseshoe Expedition of 1716 crossed the Blue Ridge at Swift Run Gap and reached the river at Elkton, Virginia. Settlers did not immediately follow, but someone who heard the reports and later became the first permanent settler in the Valley was Adam Miller (Mueller), who in 1727 staked out claims on the south fork of the Shenandoah River, near the line that now divides Rockingham County from Page County.[7]

The Great Wagon Road (later called the Valley Pike or Valley Turnpike) began as the Great Warriors Trail or Indian Road, a Native road through common hunting grounds shared by several tribes settled around the periphery, which included Iroquoian, Siouan and Algonquian-language family tribes. Known native settlements within the Valley were few, but included the Shawnee occupying the region around Winchester, and Tuscarora around what is now Martinsburg, West Virginia. In the late 1720s and 1730s, Quakers and Mennonites began to move in from Pennsylvania. They were tolerated by the natives, while "Long Knives" (English settlers from coastal Virginia colony) were less welcomed. During these same decades, the valley route continued to be used by war parties of Seneca (Iroquois) and Lenape en route from New York, Pennsylvania and New Jersey to attack the distant Catawba in the Carolinas, with whom they were at war. The Catawba in turn pursued the war parties northward, often overtaking them by the time they reached the Potomac. Several fierce battles were fought among the warring nations in the Valley region, as attested by the earliest European-American settlers.[8]

Later colonists called this route the Great Wagon Road; it became the major thoroughfare for immigrants' moving by wagons from Pennsylvania and northern Virginia into the backcountry of the South. The Valley Turnpike Company improved the road by paving it with macadam prior to the Civil War and set up toll gates to collect fees to pay for the improvements. After the advent of motor vehicles, the road was refined and paved appropriately for their use. In the 20th century, the road was acquired by the Commonwealth of Virginia, which incorporated it into the state highway system as U.S. Route 11. For much of its length, the newer Interstate 81, constructed in the 1960s, parallels the old Valley Pike.

Along with the first German settlers, known as "Shenandoah Deitsch", many Scotch-Irish immigrants came south in the 1730s from Pennsylvania into the valley, via the Potomac River. The Scotch-Irish comprised the largest group of non-English immigrants from the British Isles before the Revolutionary War, and most migrated into the backcountry of the South.[9] This was in contrast to the chiefly English immigrants who had settled the Virginia Tidewater and Carolina Piedmont regions.

Governor Spotswood had arranged the Treaty of Albany with the Iroquois (Six Nations) in 1721, whereby they had agreed not to come east of the Blue Ridge in their raiding parties on tribes farther to the South. In 1736, the Iroquois began to object, claiming that they still legally owned the land to the west of the Blue Ridge; this led to a skirmish with Valley settlers in 1743. The Iroquois were on the verge of declaring war on the Virginia Colony as a result, when Governor Gooch paid them the sum of 100 pounds sterling for any settled land in the Valley that was claimed by them. The following year at the Treaty of Lancaster, the Iroquois sold all their remaining claim to the Valley for 200 pounds in gold.[10]

The few Shawnees who still resided in the Valley abruptly headed westward in 1754, having been approached the year before by emissaries from their kindred beyond the Alleghenies.[11]

19th century

The Shenandoah Valley was known as the breadbasket of the Confederacy during the Civil War and was seen as a backdoor for Confederate raids on Maryland, Washington, and Pennsylvania. Because of its strategic importance it was the scene of three major campaigns. The first was the Valley Campaign of 1862, in which Confederate General Stonewall Jackson defended the valley against three numerically superior Union armies. The final two were the Valley Campaigns of 1864. First, in the summer of 1864, Confederate General Jubal Early cleared the valley of its Union occupiers and then proceeded to raid Maryland, Pennsylvania, and D.C. Then during the autumn, Union General Philip Sheridan was sent to drive Early from the valley and once-and-for-all destroy its use to the Confederates by putting it to the torch using scorched-earth tactics. The valley, especially in the lower northern section, was also the scene of bitter partisan fighting as the region's inhabitants were deeply divided over loyalties, and Confederate partisan John Mosby and his Rangers frequently operated in the area.

20th century

A series of newspaper mergers, ending in 1914, established the Daily News-Record of Harrisonburg as the daily newspaper of the Shenandoah Valley.

In the late 20th century, the valley's vineyards began to reach maturity. They constituted the new industry of the Shenandoah Valley American Viticultural Area.

21st century

In 2018, a series of strikes and protests were held in Dayton's Cargill plant.[12][13]

Transportation

Transportation in the Shenandoah Valley consists mainly of road and rail and contains several metropolitan area transit authorities. The main north-south road transportation is Interstate 81, which parallels the old Valley Turnpike (U.S. Route 11) and the ancient Great Path of the Native Americans through its course in the valley. In the lower (northern) valley, on the eastern side, U.S. Route 340 also runs north-south, starting from Waynesboro in the south, running through the Page Valley to Front Royal, and on to Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, where it exits the valley into Maryland. Major east-west roads cross the valley as well, providing access to the Piedmont and the Allegheny Mountains. Starting from the north, these routes include U.S. Route 50, U.S. Route 522, Interstate 66, U.S. Route 33, U.S. Route 250, Interstate 64, and U.S. Route 60.

CSX Transportation operates several rail lines through the valley, including the old Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, the old Manassas Gap Railroad and the old Virginia Central Railroad. There are also more modern lines that run the length of the valley parallel to the Valley Pike and U.S. 340. The rail lines are primarily used for freight transportation, though Maryland Area Rail Commuter (MARC) trains utilize the old B&O line from stations in Martinsburg, Duffields, and Harper's Ferry to Washington Union Station and vice versa.

Several localities in the valley operate public transportation systems, including Front Royal Area Transit (FRAT), which provides weekday transit for the town of Front Royal; Page County Transit, providing weekday transit for the town of Luray and weekday service between Luray and Front Royal; and Winchester Transit, which provides weekday transit for the city of Winchester. In addition, Shenandoah Valley Commuter Bus Service offers weekday commuter bus service from the northern Shenandoah Valley, including Shenandoah County and Warren County, to Northern Virginia (Arlington County and Fairfax County) and Washington. Origination points in Shenandoah County include Woodstock. Origination points in Warren County include Front Royal and Linden.

In popular culture

The Shenandoah Valley serves as the setting for the 1965 film Shenandoah and its 1974 musical adaptation. Both stories follow the Anderson family during the Civil War. An associated song by James Stewart titled "The Legend of Shenandoah" was a very minor hit in 1965, reaching #133 on the Billboard Bubbling Under the Hot 100 chart. One of the most famous cultural references to the area does not mention the valley itself: West Virginia's state song, "Take Me Home, Country Roads" by John Denver, simply contains the words "Shenandoah River" in the first verse.

It is also featured in the fifth season of The 100.

See also

- Blue Ridge Community and Technical College

- Bridgewater College

- Christendom College

- Eastern Mennonite University

- Frontier Culture Museum of Virginia

- George Washington National Forest

- Harpers Ferry National Historical Park

- James Madison University

- Mary Baldwin University

- Museum of the Shenandoah Valley

- Natural Bridge (Virginia)

- Polyface Farm

- Shenandoah National Park

- Shenandoah University

- Shenandoah Valley Academy

- Shepherd University

- Southern Virginia University

- Valley Baseball League

- Virginia Military Institute

- Washington and Lee University

References

- Sheehan-Dean, Aaron, Why Confederates Fought, Family and Nation in Civil War Virginia, Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2007, pg. 26

- Julia Davis, "The Shenandoah", Rivers of America, New York: Farrar & Rinehart, Inc., 1945, pp. 20–21

- Carrie Hunter Willis and Etta Belle Walker, 1937, Legends of the Skyline Drive and the Great Valley of Virginia, pp. 15–16.

- Doddridge, p. 31.

- "Cultural Heritage: American Revolution", 5 July 2010, Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin

- "The Revolutionary War", 5 July 2010, Oneida Indian Nation

- John W. Wayland, Ph.D., 1912, A History of Rockingham County, Virginia p. 33–37

- Joseph Doddridge, 1850, A History of the Valley of Virginia p. 1–46

- David Hackett Fischer, Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America, New York: Oxford University Press, 1989, pp.605–608

- Joseph Solomon Walton, 1900, Conrad Weiser and the Indian Policy of Colonial Pennsylvania p. 76-121.

- Doddridge, p.44–45

- Barnett, Marina (November 21, 2017). "Community Solidarity with Poultry Workers call for changes at Cargill". WHSV-TV. Gray Television. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- Wood, Victoria (April 5, 2018). "Nine protesters arrested outside Cargill in Dayton". WHSV-TV. Gray Television. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shenandoah Valley. |

- Shenandoah Valley - Official state tourism website

- Visit Shenandoah website

- Shenandoah Valley Technology Council

- Shenandoah at War, the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation

- CivilWarTraveler.com - Virginia's Valley and Mountains

- Valley Conservation Council

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Shenandoah Valley

- "The Shenandoah Valley", Southern Spaces, 20 April 2004

- Virginia Historical Society article "Featuring 52 masterful landscape paintings by Washington, D.C. based artist Andrei Kushnir, Oh, Shenandoah: Landscapes of Diversity explores the extraordinary beauty of the Shenandoah Valley region and the diverse history of its settlement."