Bayern-class battleship

The Bayern class was a class of four super-dreadnought battleships built by the German Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy). The class comprised Bayern, Baden, Sachsen, and Württemberg. Construction started on the ships shortly before World War I; Baden was laid down in 1913, Bayern and Sachsen followed in 1914, and Württemberg, the final ship, was laid down in 1915. Only Baden and Bayern were completed, due to shipbuilding priorities changing as the war dragged on. It was determined that U-boats were more valuable to the war effort, and so work on new battleships was slowed and ultimately stopped altogether. As a result, Bayern and Baden were the last German battleships completed by the Kaiserliche Marine.[1]

SMS Bayern | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Operators: |

|

| Preceded by: | König class |

| Succeeded by: | L 20e α class (planned) |

| Built: | 1913–1917 |

| In commission: | 1916–1919 |

| Planned: | 4 |

| Completed: | 2 |

| Lost: | 2 |

| Scrapped: | 1 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Super-dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement: | |

| Length: | |

| Beam: | 30 m (98 ft 5 in) |

| Draft: | 9.39 m (30 ft 10 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range: | 5,000 nmi (9,300 km; 5,800 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Complement: | 1,187–1,271 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

Bayern and Baden were commissioned into the fleet in July 1916 and March 1917, respectively. This was too late for either ship to take part in the Battle of Jutland on 31 May and 1 June 1916. Bayern was assigned to the naval force that drove the Imperial Russian Navy from the Gulf of Riga during Operation Albion in October 1917, though the ship was severely damaged by a mine and had to be withdrawn to Kiel for repairs. Baden replaced Friedrich der Grosse as the flagship of the High Seas Fleet, but saw no combat.

Both Bayern and Baden were interned at Scapa Flow following the Armistice in November 1918. Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter, the commander of the interned German fleet, ordered his ships be sunk on 21 June 1919; Bayern was successfully scuttled, though British guards managed to beach Baden to prevent her from sinking. The ship was expended as a gunnery target in 1921. Sachsen and Württemberg, both at various stages of completion when the war ended, were broken up for scrap metal. Bayern was raised in 1934 and broken up the following year.

Design

Design work on the class began as early as 1910, with great consideration given to the armament of the new vessels. It had become clear that other navies were moving to guns larger than 30.5 cm (12 in), and so the next German battleship would also have to incorporate larger guns. The Weapons Department suggested a 32 cm (13 in) gun, but during a meeting on 11 May 1910, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, the State Secretary of the Reichsmarineamt (Imperial Naval Office), decided that budgetary constraints precluded the adoption of larger weapons. The following year, in the aftermath of the Agadir Crisis, Tirpitz quickly seized on public outcry over the British involvement in the crisis to pressure the Reichstag (Imperial Diet) into appropriating additional funds for the Navy. This provided the opening for more powerful battleships, so Tirpitz requested funds for ships armed with 34 cm (13.4 in) guns in mid-1911.[2][3]

In August that year, the design staff prepared studies for ships armed with 35 cm (13.8 in), 38 cm (15 in), and 40 cm (15.7 in) guns; the 40 cm caliber was set as the maximum, since it was (incorrectly) assumed that British wire-wound guns larger than that could not be built. During a meeting the following month, the preferred designs were a ship armed with ten 35 cm guns in five turrets or eight 40 cm guns in four turrets. The Weapons Department advocated the 35 cm gun ship, pointing out that it would have a 25% greater chance of hitting its target. Tirpitz inquired about a mixed battery of twin and triple turrets,[2][3] but after examining the gun turrets of the Austro-Hungarian dreadnoughts of the Tegetthoff class, it was determined that the triple gun turrets still had too many problems. Among these deficiencies were increased weight, reduced ammunition supply and rate of fire, and loss of fighting capability if one of the turrets was disabled.[1]

Design studies suggested that the 35 cm ship would displace around 29,000 t (29,000 long tons) and cost around 59.7 million marks, while the 40 cm proposal would cost approximately 60 million marks and displace 28,250 t (27,800 long tons), but both of these ships were deemed to be too expensive. The Construction Department proposed a 28,100 t (27,700 long tons) ship armed with eight 38 cm guns, which reduced the cost to 57.5 million marks per vessel. This design was adopted as the basis for the next class of battleship on 26 September, and the decision to adopt the 38 cm gun was formally taken on 6 January 1912.[2] Work continued on the design into 1912, and included further developing the armor layout that had been adopted in the previous König class. The ships were originally projected to be armed with eight 8.8 cm (3.5 in) anti-aircraft guns, though they were not completed with any. Since the development of diesel engines was proving to be problematic, the design staff adopted traditional steam turbines for the ships, though it was hoped that by the time the third member of the class was ready to begin construction, reliable diesel engines would be available.[4]

Funding for the vessels was allocated under the fourth Naval Law, which was passed in 1912. The Fourth Naval Law secured funding for three new dreadnoughts, two light cruisers, and an increase of an additional 15,000 officers and men in the ranks of the Navy for 1912.[5] The capital ships laid down in 1912 were the Derfflinger-class battlecruisers; funding for Bayern and Baden was allocated the following year.[6][7] Funding for Sachsen was allocated in the 1914 budget, while Württemberg was funded in the War Estimates.[8] The last remaining Brandenburg-class pre-dreadnought, Wörth, was to be replaced, as well as two elderly Kaiser Friedrich III-class pre-dreadnoughts, Kaiser Wilhelm II and Kaiser Friedrich III. Baden was ordered as Ersatz Wörth, Württemberg as Ersatz Kaiser Wilhelm II, and Sachsen as Ersatz Kaiser Friedrich III; Bayern was regarded as an addition to the fleet, and was ordered under the provisional name "T".[9][lower-alpha 1]

General characteristics

Bayern and Baden were 179.4 m (588 ft 7 in) long at the waterline, and an even 180 m (590 ft 7 in) long overall. Sachsen and Württemberg were slightly longer: 181.8 m (596 ft 5 in) at the waterline and 182.4 m (598 ft 5 in) overall. All four ships had a beam of 30 m (98 ft 5 in), and had a draft of between 9.3 and 9.4 m (30 ft 6 in and 30 ft 10 in). Bayern and Baden were designed to displace 28,530 t (28,080 long tons) at a normal displacement; at full combat load, the ships displaced up to 32,200 t (31,700 long tons). Württemberg and Sachsen were slightly heavier, at 28,800 t normal and 32,500 t fully laden. The ships were constructed with transverse and longitudinal steel frames, over which the outer hull plates were riveted. The hull was divided into 17 watertight compartments, and included a double bottom that ran for 88 percent of the length of the hull.[9]

Bayern and Baden were regarded as exceptional sea boats by the German navy. Bayern and her sisters were stable and very maneuverable. The ships suffered slight speed loss in heavy seas; with the rudders hard over, the ships lost up to 62% speed and heeled over 7 degrees. With a metacentric height of 2.53 m (8 ft 4 in),[10] larger than that of their British equivalents, the vessels were stable gun platforms for the confined waters of the North Sea.[11][lower-alpha 2] The ships of the Bayern class had a standard crew of 42 officers and 1,129 enlisted men; when serving as a squadron flagship, an additional 14 officers and 86 men were required. The vessels carried several smaller craft, including one picket boat, three barges, two launches, two yawls, and two dinghies.[10]

Machinery

Bayern and Baden were equipped with eleven coal-fired Schulz-Thornycroft boilers and three oil-fired Schulz-Thornycroft boilers in nine boiler rooms. Three sets of Parsons turbines drove three-bladed screws that were 3.87 m (12.7 ft) in diameter. Bayern's and Baden's power plant was designed to run at 34,521 shaft horsepower (25,742 kW) at 265 revolutions per minute; on trials the ships achieved 55,201 shp (41,163 kW) and 55,505 shp (41,390 kW), respectively. Both ships were capable of a maximum speed of 22 knots (41 km/h; 25 mph). The first two ships were designed to carry 900 t (890 long tons) of coal and 200 t (200 long tons) of oil, though the use of additional spaces in the hull increased the total bunkerage to 3,400 t (3,300 long tons) of coal and 620 t (610 long tons) of oil. This enabled a range of 5,000 nautical miles (9,300 km; 5,800 mi) at a speed of 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph). At 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph), the range decreased to 4,485 nmi (8,306 km; 5,161 mi), at 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph) the range fell to 3,740 nmi (6,930 km; 4,300 mi), and at 21.5 knots (39.8 km/h; 24.7 mph) the ships could steam for only 2,390 nmi (4,430 km; 2,750 mi). The ships carried eight diesel generators; these supplied each ship with a total of 2,400 kilowatts of electrical power at 220 volts.[9]

Sachsen and Württemberg were intended to be one knot faster than the earlier pair of ships.[12] Württemberg received more powerful machinery that would have produced 47,343 shp (35,304 kW) for a designed speed of 22 knots. On Sachsen, a MAN diesel engine producing 11,836 bhp (8,826 kW) was to be installed on the center shaft, while steam turbines powered the outboard shafts, but the diesel engine was not ready by the end of the war, and it was only completed in 1919 for testing by the Naval Inter-Allied Control Commission. The combined power plant would have produced 53,261 shp (39,717 kW) for a designed speed of 22.5 knots.[9][13]

Armament

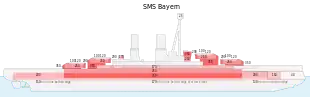

The Bayern-class battleships were armed with a main battery of eight 38 cm (15 in) SK L/45 guns[lower-alpha 3] in four Drh LC/1913 twin gun turrets. These turrets allowed for depression of the guns to −8 degrees and elevation to 16 degrees. The guns had to be returned to 2.5 degrees to reload them. The gun mountings for Bayern were later modified to allow elevation up to 20 degrees, though the changes reduced depression to −5 degrees. As originally configured, the guns had a maximum range of 20,250 m (66,440 ft), but Bayern's modified guns could reach 23,200 m (76,100 ft). Each turret was fitted with a stereo rangefinder. The main battery was supplied with a total of 720 shells or 90 rounds per gun; these were 750-kilogram (1,650 lb) shells that were light for guns of their caliber. The shell allotment was divided between armor piercing and high explosive versions, with 60 of the former and 30 of the latter. At a range of 20,000 m (66,000 ft), the armor-piercing shells could penetrate up to 336 mm (13.2 in) of steel plate. The guns had a rate of fire of around one shell every 38 seconds. Muzzle velocity was 805 meters per second (2,640 ft/s).[10][14][15]

Post-war tests conducted by the British Royal Navy showed that the guns on Baden could be ready to fire again 23 seconds after firing; this was significantly faster than their British contemporaries, the Queen Elizabeth class, which took 36 seconds between salvos. While the German guns were faster to reload, the British inspectors found German anti-flash precautions to be significantly inferior to those that had been adopted by the Royal Navy after 1917, though this was to some degree mitigated by the brass propellant cases, which were far less susceptible to flash detonations than the silk-bagged British cordite. The guns that had been constructed for the battleships Sachsen and Württemberg were used as long-range, heavy siege guns on the Western Front, as coastal guns in occupied France and Belgium, and a few as railway guns; these guns were referred to as Langer Max.[16]

The ships were also armed with a secondary battery of sixteen 15 cm (5.9 in) SK L/45 quick-firing guns, each mounted in armored casemates in the side of the top deck. These guns were intended for defense against torpedo boats, and were supplied with a total of 2,240 shells. The guns could engage targets out to 13,500 m (44,300 ft), and after improvements in 1915, their range was extended to 16,800 m (55,100 ft). The guns had a sustained rate of fire of 5 to 7 rounds per minute. The shells were 45.3 kg (99.8 lb), and were loaded with a 13.7 kg (31.2 lb) RPC/12 propellant charge in a brass cartridge. The guns fired at a muzzle velocity of 835 meters per second (2,740 ft/s). The guns were expected to fire around 1,400 shells before they needed to be replaced. Bayern and Baden were also equipped with a pair of 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK L/45 flak guns, which were supplied with 800 rounds.[10] The guns were emplaced in MPL C/13 mountings, which allowed depression to −10 degrees and elevation to 70 degrees. These guns fired 9 kg (19.8 lb) shells, and had an effective ceiling of 9,150 m (30,020 ft) at 70 degrees.[17][18]

As was customary on capital ships of the period, the Bayern-class ships were armed with five 60 cm (24 in) submerged torpedo tubes. One tube was mounted in the bow and two on each broadside. A total of 20 torpedoes were carried per ship. When both Bayern and Baden struck mines in 1917, the damage incurred revealed structural weaknesses caused by the torpedo tubes and both ships had their lateral tubes removed.[10] The torpedoes were the H8 type, which were 9 m (30 ft) long and carried a 210 kg (463 lb) Hexanite warhead. The torpedoes had a range of 8,000 m (8,700 yd) when set at a speed of 35 knots (65 km/h; 40 mph); at a reduced speed of 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph), the range increased significantly to 15,000 m (16,000 yd).[19][20]

Armor

The Bayern-class ships were protected with Krupp cemented steel armor, as was the standard for German warships of the period. They had an armor belt that was 350 mm (14 in) thick in the central citadel of the ship, where the most important parts of the ship were located. This included the ammunition magazines and the machinery spaces. The belt was reduced in less critical areas, to 200 mm (7.9 in) forward and 170 mm (6.7 in) aft. The bow and stern were not protected by armor at all. A 50 mm (2 in)-thick torpedo bulkhead ran the length of the hull, several meters behind the main belt. The main armored deck was 60 mm (2.4 in) thick in most places, though the thickness of the sections that covered the more important areas of the ship was increased to 100 mm (3.9 in).[9]

The forward conning tower was protected with heavy armor: the sides were 400 mm (16 in) thick and the roof was 170 mm thick. The rear conning tower was less well armored; its sides were only 170 mm thick and the roof was covered with 80 mm (3.1 in) of armor plate. The main battery gun turrets were also heavily armored: the turret sides were 350 mm thick and the roofs were 200 mm thick. The 15 cm guns had 170 mm thick armor plating on the casemates; the guns themselves had 80 mm thick shields to protect their crews from shell splinters.[9]

Sachsen's armor layout was modified slightly as a result of the planned diesel engine, which was significantly taller than a turbine. A glacis over the diesel was added that was 200 mm thick on the sides, 140 mm (5.5 in) thick on either end, and 80 mm thick on top. Her belt was also slightly modified, with 30 mm (1.2 in) extending past the forward 200 mm thick section all the way to the stem.[21]

Construction

.jpg.webp)

The class was planned to include four ships. Bayern was built by Howaldtswerke in Kiel under construction number 590; she was laid down in 1913, launched on 18 February 1915, and completed on 15 July 1916. Baden was built by the Schichau shipyard in Danzig, under construction number 913. The ship was launched on 30 October 1915 and commissioned into the fleet on 14 March 1917. Sachsen was laid down at the Germaniawerft dockyard in Kiel, under construction number 210. She was launched on 21 November 1916, but not completed.[22] Sachsen was by then 9 months from completion.[23] Württemberg was constructed by AG Vulcan shipyard in Hamburg under construction number 19. She was launched on 20 June 1917, but she too was not completed and scrapped in 1921.[22] At the time of cancellation, Württemberg was approximately 12 months from completion.[23]

Ships

| Ship | Builder | Namesake | Laid down | Launched | Commissioned | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bayern | Howaldtswerke, Kiel[10] | Bavaria | 22 December 1913[24] | 18 February 1915[10] | 15 July 1916[10] | Scuttled at Scapa Flow, 21 June 1919[10] |

| Baden | Schichau-Werke, Danzig[10] | Baden | 20 December 1913[24] | 30 October 1915[10] | 14 March 1917[10] | Sunk as target, August 1921[10] |

| Sachsen | Germaniawerft, Kiel[10] | Saxony | 15 April 1914[25] | 21 November 1916[10] | Cancelled prior to completion, scrapped in 1921[10] | |

| Württemberg | AG Vulcan, Hamburg[10] | Württemberg | 4 January 1915[26] | 20 June 1917[10] | ||

Service history

Fleet sortie of 18–19 August 1916

During the fleet sortie on 18–19 August 1916, I Scouting Group, which was the battlecruiser reconnaissance force of the High Seas Fleet and commanded by Admiral Franz von Hipper, was to bombard the coastal town of Sunderland in an attempt to draw out and destroy Beatty's battlecruisers. As Moltke and Von der Tann were the only two remaining German battlecruisers still in fighting condition after the Battle of Jutland, three dreadnoughts were assigned to the unit for the operation: Bayern, and the two König-class ships Markgraf and Grosser Kurfürst. Admiral Scheer and the rest of the High Seas Fleet, with 15 dreadnoughts of its own, would trail behind and provide cover.[27] The British were aware of the German plans and sortied the Grand Fleet to meet them. By 14:35, Scheer had been warned of the Grand Fleet's approach and, unwilling to engage the whole of the Grand Fleet just 11 weeks after the decidedly close call at Jutland, turned his forces around and retreated to German ports.[28]

Operation Albion

In early September 1917, following the German conquest of the Russian port of Riga, the German navy decided to evict the Russian naval forces that still held the Gulf of Riga. To this end, the Admiralstab (the Navy High Command) planned an operation to seize the Baltic islands of Ösel, particularly the Russian gun batteries on the Sworbe peninsula.[29] On 18 September, the order was issued for a joint Army-Navy operation to capture Ösel and Moon islands; the primary naval component was to comprise the flagship, the battlecruiser Moltke, along with III Battle Squadron of the High Seas Fleet. V Division included the four König-class battleships, and was by this time augmented with Bayern. VI Division consisted of the five Kaiser-class battleships. Along with nine light cruisers, 3 torpedo boat flotillas, and dozens of mine warfare ships, the entire force numbered some 300 ships, and were supported by over 100 aircraft and 6 zeppelins. The invasion force amounted to approximately 24,600 officers and enlisted men.[30] Opposing the Germans were the old Russian pre-dreadnoughts Slava and Tsesarevich, the armored cruisers Bayan, Admiral Makarov, and Diana, 26 destroyers, and several torpedo boats and gunboats. The garrison on Ösel numbered some 14,000 men.[31]

The operation began on 12 October, when Moltke, Bayern, and the Königs began firing on the Russian shore batteries at Tagga Bay. Simultaneously, the Kaisers engaged the batteries on the Sworbe peninsula; the objective was to secure the channel between Moon and Dagö islands, which would block the only escape route of the Russian ships in the gulf. Both Grosser Kurfürst and Bayern struck mines while maneuvering into their bombardment positions; damage to the former was minimal, and the ship remained in action. Bayern was severely damaged, and temporary repairs proved ineffective. The ship had to be withdrawn to Kiel for repairs; the return trip took 19 days.[31]

Fleet sortie of 23–24 April 1918

In late 1917, the High Seas Fleet began to conduct anti-convoy raids with light craft in the North Sea between Britain and Norway. On 17 October, the German light cruisers Brummer and Bremse intercepted a convoy of twelve ships escorted by a pair of destroyers and destroyed it; only three transports managed to escape. On 12 December, four German destroyers intercepted and annihilated another convoy of five ships and two escorting destroyers. This prompted Admiral David Beatty, the Commander in Chief of the Grand Fleet, to detach several battleships and battlecruisers to protect the convoys in the North Sea.[32] This presented to Admiral Scheer the opportunity for which he had been waiting the entire war: the chance to isolate and eliminate a portion of the Grand Fleet.[33]

At 05:00 on 23 April 1918, the entire High Seas Fleet, including Bayern and Baden, left harbor with the intention of intercepting one of the heavily escorted convoys. Wireless radio traffic was kept to a minimum to prevent the British from learning of the operation. At 05:10 on 24 April, the battlecruiser Moltke suffered severe mechanical problems and had to be towed back to Wilhelmshaven. By 14:10, the convoy had still not yet been located, and so Scheer turned the High Seas Fleet back towards German waters. In fact, there was no convoy sailing on 24 April; German naval intelligence had miscalculated the sailing date by one day.[33]

Wilhelmshaven mutiny

In October 1918, Admiral Hipper, now the commander of the entire High Seas Fleet, planned for a final battle with the Grand Fleet. Admiral Reinhard Scheer, the Chief of the Naval Staff, approved the plan on 27 October; the operation was set for the 30th.[34] When the fleet was ordered to assemble in Wilhelmshaven on 29 October, war-weary crews began to desert or openly disobey their orders. Crews aboard the battleships König, Kronprinz, and Markgraf demonstrated for peace. The crew aboard Thüringen was the first to openly mutiny; Helgoland and Kaiserin joined as well.[35] By the evening of the 29th, red flags of revolution flew from the masts of dozens of warships in the harbor. In spite of this, Hipper decided to hold a last meeting aboard Baden—his flagship—to discuss the operation with the senior officers of the fleet. The following morning, it was clear the mutiny was too far gone to permit a fleet action. In an attempt to suppress the revolt, he ordered one of the battle squadrons to depart for Kiel.[36] By 5 November, red flags had been raised on every battleship in the harbor except König, though it too was commandeered by a sailors' council on 6 November.[37]

Fate

Following the armistice with Germany in November 1918, the majority of the High Seas Fleet was to be interned in the British naval base at Scapa Flow.[38] Bayern was listed as one of the ships to be handed over, though Baden initially was not. The battlecruiser Mackensen, which the British believed to be completed, was requested instead. When it became apparent to the Allies that Mackensen was still under construction, Baden was ordered to replace it.[39] On 21 November 1918, the ships to be interned, under the command of Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter, sailed from their base in Germany for the last time. The fleet rendezvoused with the light cruiser HMS Cardiff, before meeting a massive flotilla of some 370 British, American, and French warships for the voyage to Scapa Flow.[40] Baden arrived at Scapa Flow separately on 14 December 1918.[41]

When the ships were interned, they had their guns disabled through the removal of their breech blocks.[39] The fleet remained in captivity during the negotiations that ultimately produced the Versailles Treaty. It became apparent to Reuter that the British intended to seize the German ships on 21 June, which was the deadline for Germany to have signed the peace treaty.[lower-alpha 4] To prevent this, he decided to scuttle his ships at the first opportunity. On the morning of 21 June, the British fleet left Scapa Flow to conduct training maneuvers; at 11:20 Reuter transmitted the order to his ships.[42] Bayern sank at 14:30, but Baden was run aground by British guards; she was the only capital ship that was not sunk. After being refloated and thoroughly examined, Baden was expended as a gunnery target, finally being sunk on 16 August 1921 to the southwest of Portsmouth. Bayern was raised for scrapping on 1 September 1934 and broken up over the following year in Rosyth.[10]

The uncompleted Sachsen and Württemberg were stricken from the German Navy under the terms of Article 186 of the Versailles Treaty. Sachsen was sold for scrapping in 1920 to ship breakers at the Kiel Arsenal. Württemberg was sold the following year, and broken up in Hamburg.[10]

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bayern class battleship. |

Footnotes

- All German ships were ordered under provisional names; additions to the fleet were given a letter, while ships that were intended to replace older vessels were ordered as "Ersatz (ship name)." An example of this practice is the Derfflinger-class battlecruisers: the lead ship SMS Derfflinger was considered an addition to the fleet, and was ordered as "K", while her sisters Lützow and Hindenburg were ordered as Ersatz Kaiserin Augusta and Ersatz Hertha, being replacements for two older ships. See: Gröner, p. 56.

- Metacentric height (the distance between the center of gravity – G—and the metacenter – M—abbreviated as GM) determines a ship's tendency to roll in the water; if the GM is too low, the ship will tend to roll severely or even risk capsizing.

- In Imperial German Navy gun nomenclature, "SK" (Schnelladekanone) denotes that the gun is quick firing, while the L/45 denotes the length of the gun. In this case, the L/45 gun is 45 caliber, meaning that the gun barrel is 45 times as long as it is in bore diameter. See: Grießmer, p. 177.

- By this time, the Armistice had been extended to 23 June, though there is some contention as to whether von Reuter was aware of this. Admiral Sydney Fremantle stated that he informed von Reuter on the evening of the 20th, though von Reuter claims he was unaware of the development. For Fremantle's claim, see Bennett, p. 307. For von Reuter's statement, see Herwig, p. 256.

Citations

- Hore, p. 70.

- Friedman, p. 131.

- Dodson, p. 97.

- Dodson, pp. 97–98.

- Herwig, p. 77.

- Herwig, p. 81.

- Sturton, p. 38.

- Sturton, p. 41.

- Gröner, p. 28.

- Gröner, p. 30.

- Lyon & Moore, p. 104.

- Greger, p. 37.

- Dodson, p. 98.

- Friedman, pp. 131–133.

- Schmalenbach, p. 79.

- Friedman, p. 133.

- Friedman, pp. 143–144, 147.

- Gardiner & Gray, pp. 140, 155.

- Friedman, p. 339.

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 155.

- Dodson, p. 99.

- Gröner, pp. 28–30.

- Herwig, p. 83.

- Nottelmann, p. 298.

- Nottelmann, p. 317.

- Nottelmann, p. 320.

- Massie, p. 682.

- Massie, p. 683.

- Halpern, p. 213.

- Halpern, pp. 214–215.

- Halpern, p. 215.

- Massie, p. 747.

- Massie, p. 748.

- Tarrant, pp. 281–281.

- Tarrant, p. 281.

- Woodman, pp. 237–238.

- Schwartz, p. 48.

- Tarrant, p. 282.

- Herwig, p. 255.

- Herwig, pp. 254–255.

- Preston, p. 85.

- Herwig, p. 256.

References

- Bennett, Geoffrey (2005). Naval Battles of the First World War. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military Classics. ISBN 978-1-84415-300-8.

- Dodson, Aidan (2016). The Kaiser's Battlefleet: German Capital Ships 1871–1918. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-229-5.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations; An Illustrated Directory. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Greger, Rene (1997). Battleships of the World. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-069-X.

- Grießmer, Axel (1999). Die Linienschiffe der Kaiserlichen Marine: 1906–1918; Konstruktionen zwischen Rüstungskonkurrenz und Flottengesetz [The Battleships of the Imperial Navy: 1906–1918; Constructions between Arms Competition and Fleet Laws] (in German). Bonn: Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7637-5985-9.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7.

- Herwig, Holger (1998) [1980]. "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9.

- Hore, Peter (2006). Battleships of World War I. London: Southwater Books. ISBN 978-1-84476-377-1.

- Lyon, Hugh & Moore, John E. (1978). The Encyclopedia of the World's Warships. London: Salamander Books. ISBN 0-517-22478-X.

- Massie, Robert K. (2003). Castles of Steel. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-40878-5.

- Nottelmann, Dirk. "From Ironclads to Dreadnoughts: The Development of the German Navy, 1864–1918: Part XA, "Lost Ambitions"". Warship International. Toledo: International Naval Research Organization. 56 (4). ISSN 0043-0374.

- Preston, Anthony (1972). Battleships of World War I: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Battleships of all Nations, 1914–1918. Harrisburg: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0211-9.

- Schmalenbach, Paul (1993). Die Geschichte der Deutschen Schiffsartillerie [The History of German Naval Artillery] (in German). Herford: Koehler. ISBN 9783782205771.

- Schwartz, Stephen (1986). Brotherhood of the Sea: A History of the Sailors' Union of the Pacific, 1885–1985. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0-88738-121-8.

- Sturton, Ian, ed. (1987). Conway's All the World's Battleships: 1906 to the Present. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-448-0.

- Tarrant, V. E. (2001) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-304-35848-9.

- Woodman, Richard (2005). A Brief History of Mutiny. Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7867-1567-1.