SMS Kronprinz

SMS Kronprinz[lower-alpha 1] was the last battleship of the four-ship König class of the German Imperial Navy. The battleship was laid down in November 1911 and launched on 21 February 1914. She was formally commissioned into the Imperial Navy on 8 November 1914, just over 4 months after the start of World War I. The name Kronprinz (Eng: "Crown Prince") refers to Crown Prince Wilhelm, and in June 1918, the ship was renamed Kronprinz Wilhelm in his honor. The battleship was armed with ten 30.5-centimeter (12.0 in) guns in five twin turrets and could steam at a top speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph).

SMS Kronprinz Wilhelm in Scapa Flow 1919 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Builder: | Germaniawerft, Kiel |

| Laid down: | November 1911 |

| Launched: | 21 February 1914 |

| Commissioned: | 8 November 1914 |

| Fate: | Scuttled 21 June 1919 in Gutter Sound, Scapa Flow |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | König-class battleship |

| Displacement: | |

| Length: | 175.4 m (575 ft 6 in) |

| Beam: | 29.5 m (96 ft 9 in) |

| Draft: | 9.19 m (30 ft 2 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range: | 8,000 nmi (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Complement: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

Along with her three sister ships, König, Grosser Kurfürst and Markgraf, Kronprinz took part in most of the fleet actions during the war, including the Battle of Jutland on 31 May and 1 June 1916. Although near the front of the German line, she emerged from the battle unscathed. She was torpedoed by the British submarine HMS J1 on 5 November 1916 during an operation off the Danish coast. Following repairs, she participated in Operation Albion, an amphibious assault in the Baltic, in October 1917. During the operation Kronprinz engaged the Tsesarevich and forced her to retreat.

After Germany's defeat in the war and the signing of the Armistice in November 1918, Kronprinz and most of the capital ships of the High Seas Fleet were interned by the Royal Navy in Scapa Flow. The ships were disarmed and reduced to skeleton crews while the Allied powers negotiated the final version of the Treaty of Versailles. On 21 June 1919, days before the treaty was signed, the commander of the interned fleet, Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter, ordered the fleet to be scuttled to ensure that the British would not be able to seize the ships. Unlike most of the other scuttled ships, Kronprinz was never raised for scrapping; the wreck is still on the bottom of the harbor.

Design

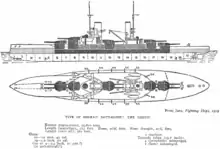

The four König-class battleships were ordered as part of the Anglo-German naval arms race; they were the fourth generation of German dreadnought battleships, and they were built in response to the British Orion class that had been ordered in 1909.[1] The Königs represented a development of the earlier Kaiser class, with the primary improvement being a more efficient arrangement of the main battery. The ships had also been intended to use a diesel engine on the center propeller shaft to increase their cruising range, but development of the diesels proved to be more complicated than expected, so an all-steam turbine powerplant was retained.[2]

Kronprinz displaced 25,796 t (25,389 long tons) as built and 28,600 t (28,100 long tons) fully loaded, with a length of 175.4 m (575 ft 6 in), a beam of 29.5 m (96 ft 9 in) and a draft of 9.19 m (30 ft 2 in). She was powered by three Parsons steam turbines, with steam provided by three oil-fired and twelve coal-fired Schulz-Thornycroft water-tube boilers, which developed a total of 45,570 shaft horsepower (33,980 kW) and yielded a maximum speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). The ship had a range of 8,000 nautical miles (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) at a cruising speed of 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph). Her crew numbered 41 officers and 1,095 enlisted men.[3]

She was armed with ten 30.5 cm (12 in) SK L/50 guns arranged in five twin gun turrets:[lower-alpha 2] two superfiring turrets each fore and aft and one turret amidships between the two funnels. Her secondary armament consisted of fourteen 15 cm (5.9 in) SK L/45 quick-firing guns and six 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK L/45 quick-firing guns, all mounted singly in casemates. As was customary for capital ships of the period, she was also armed with five 50 cm (19.7 in) underwater torpedo tubes, one in the bow and two on each beam.[5]

The ship's armored belt consisted of Krupp cemented steel that was 35 cm (13.8 in) thick in the central portion that protected the propulsion machinery spaces and the ammunition magazines, and was reduced to 18 cm (7.1 in) forward and 12 cm (4.7 in) aft. In the central portion of the ship, horizontal protection consisted of a 10 cm (3.9 in) deck, which was reduced to 4 cm (1.6 in) on the bow and stern. The main battery turrets had 30 cm (11.8 in) of armor plate on the sides and 11 cm (4.3 in) on the roofs, while the casemate guns had 15 cm (5.9 in) of armor protection. The sides of the forward conning tower were also 30 cm thick.[5]

Service history

Kronprinz was ordered under the provisional name Ersatz Brandenburg and built at the Germaniawerft shipyard in Kiel under construction number 182.[3][lower-alpha 3] Her keel was laid in May 1912 and she was launched on 21 February 1914.[6] The ship's namesake, Crown Prince Wilhelm, was to have given the launching speech, but he was sick at the time so Prince Heinrich, the General Inspector of the Navy, gave it in his place. Crown Princess Cecile christened the ship.[7] The ship was scheduled to be completed in early 1915, but work was expedited after the outbreak of World War I in mid-1914.[8] Fitting-out work was completed by 8 November 1914, the day she was commissioned into the High Seas Fleet.[5] Kronprinz was completed in November 1914; following her commissioning she joined III Battle Squadron of the High Seas Fleet.[9] Gottfried von Dalwigk zu Lichtenfels served as the ship's first commander.[10]

Kronprinz completed her sea trials on 2 January 1915. The first operation in which she participated was an uneventful sortie by the fleet into the North Sea on 29–30 March. Three weeks later, on 17–18 April, she and her sisters supported an operation in which the light cruisers of II Scouting Group laid mines off the Swarte Bank. Another sweep by the fleet occurred on 22 April; two days later III Squadron returned to the Baltic for another round of exercises.[11] On 8 May an explosion occurred in the center turret's right gun. The Baltic exercises lasted until 13 May, at which point III Squadron returned to the North Sea.[8] Another minelaying operation was conducted by II Scouting Group on 17 May, with the battleship again in support.[11]

Kronprinz participated in a fleet operation into the North Sea which ended without combat from 29 until 31 May 1915.[8] In August, Constanz Feldt replaced Dalwigk zu Lichtenfels as the ship's captain.[10] The ship supported a minelaying operation on 11–12 September off Texel. The fleet conducted another sweep into the North Sea on 23–24 October. Several uneventful sorties followed on 5–7 March 1916, 31 March and 2–3 April.[8] Kronprinz supported a raid on the English coast on 24 April 1916 conducted by the German battlecruiser force of I Scouting Group. The battlecruisers left the Jade Estuary at 10:55 CET,[lower-alpha 4] and the rest of the High Seas Fleet followed at 13:40. The battlecruiser Seydlitz struck a mine while en route to the target, and had to withdraw.[12] The other battlecruisers bombarded the town of Lowestoft unopposed, but during the approach to Yarmouth, they encountered the British cruisers of the Harwich Force. A short gun duel ensued before the Harwich Force withdrew. Reports of British submarines in the area prompted the retreat of I Scouting Group. At this point, Admiral Reinhard Scheer, who had been warned of the sortie of the Grand Fleet from its base in Scapa Flow, also withdrew to safer German waters.[13]

Battle of Jutland

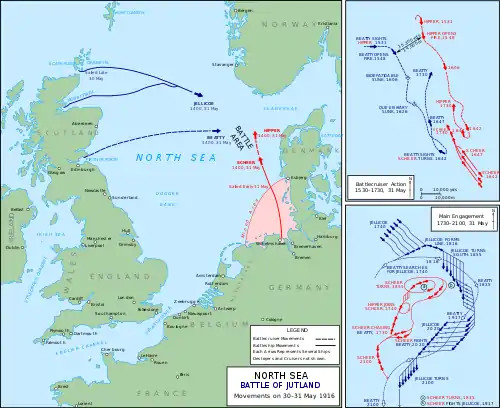

Kronprinz was present during the fleet operation that resulted in the battle of Jutland which took place on 31 May and 1 June 1916. The German fleet again sought to draw out and isolate a portion of the Grand Fleet and destroy it before the main British fleet could retaliate. Kronprinz was the rearmost ship of V Division, III Battle Squadron, the vanguard of the fleet. She followed her sisters König, the lead ship, Grosser Kurfürst, and Markgraf. III Battle Squadron was the first of three battleship units; directly astern were the Kaiser-class battleships of VI Division, III Battle Squadron. Directly astern of the Kaiser-class ships were the Helgoland and Nassau classes of II Battle Squadron; in the rear guard were the obsolescent Deutschland-class pre-dreadnoughts of I Battle Squadron.[14]

Shortly before 16:00, the battlecruisers of I Scouting Group encountered the British 1st Battlecruiser Squadron under the command of David Beatty. The opposing ships began an artillery duel that saw the destruction of Indefatigable, shortly after 17:00,[15] and Queen Mary, less than half an hour later.[16] By this time, the German battlecruisers were steaming south to draw the British ships toward the main body of the High Seas Fleet. At 17:30, König's crew spotted both I Scouting Group and the 1st Battlecruiser Squadron approaching. The German battlecruisers were steaming to starboard, while the British ships steamed to port. At 17:45, Scheer ordered a two-point turn to port to bring his ships closer to the British battlecruisers, and a minute later, the order to open fire was given.[17][lower-alpha 5]

Kronprinz's sisters opened fire on the British battlecruisers, but Kronprinz was not close enough to engage them. Instead, she and ten other German battleships fired at the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron.[18] Kronprinz fired at HMS Dublin from 17:51 to 18:00 at ranges of 17,000–18,600 m (55,800–61,000 ft), then shifted her fire to the fast battleship Malaya at 18:08 at a range of 17,000 m. Kronprinz fired first with semi-armor-piercing shells to find the range to her target, then with standard armor-piercing shells. By the time Malaya drew out of range 13 minutes later, only one hit had been reported by Kronprinz's gunners. According to naval historian John Campbell, this hit was more likely "the flash of the Malaya's guns seen through haze and smoke".[19] During this period, several salvos fell close to Kronprinz, though none struck her.[20] Kronprinz again reached a firing position against Malaya at 18:30, but was only able to fire for six minutes before the British ship again pulled away.[21]

Shortly after 19:00, several British destroyers attempted a torpedo attack against the leading ships of the German line. The destroyer Onslow fired a pair of torpedoes at Kronprinz at a range of 7,300 m (24,000 ft), though both missed.[22] The German cruiser Wiesbaden had been disabled by a shell from the British battlecruiser Invincible, and Rear Admiral Paul Behncke in König ordered his four ships to maneuver to cover the stricken cruiser.[23] Simultaneously, the British III and IV Light Cruiser Squadrons began a torpedo attack on the German line; while advancing to torpedo range, they smothered Wiesbaden with fire from their main guns. Kronprinz and her sisters fired heavily on the British cruisers, but failed to drive them off.[24] In the ensuing melee, the British armored cruiser Defence was struck by several heavy caliber shells from the German dreadnoughts. One salvo penetrated the ship's ammunition magazines and, in a massive explosion, destroyed the cruiser.[25] John Campbell notes that although Defence's destruction is usually attributed to the battlecruiser Lützow, there is a possibility that it was Kronprinz's fire that destroyed the ship.[26] After the destruction of Defence, Kronprinz shifted her fire to Warrior; the British cruiser was badly damaged and forced to withdraw from the battle. She was unable to reach port, and was abandoned the following morning.[27]

By 20:00, the German line was ordered to turn eastward to disengage from the British fleet.[28] Markgraf, directly ahead of Kronprinz, had engine problems and fell out of formation, then fell in behind Kronprinz.[29] Between 20:00 and 20:30, Kronprinz and the other III Squadron battleships engaged the British 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron as well as the battleships of the Grand Fleet. Kronprinz attempted to find the range by observing the British muzzle flashes, but the worsening visibility prevented her gunners from acquiring a target. As a result, she held her fire in this period.[30] Kronprinz was violently shaken by several near misses.[31] At 20:18, Scheer ordered the fleet to turn away a third time to escape from the murderous British gunfire; this turn reversed the order of the fleet and placed Kronprinz toward the end of the line.[32] After successfully withdrawing from the British, Scheer ordered the fleet to assume night cruising formation, though communication errors between Scheer aboard Friedrich der Grosse and Westfalen, the lead ship, caused delays. The fleet fell into formation by 23:30, with Kronprinz the 14th vessel in the line of 24 capital ships.[33]

Around 02:45, several British destroyers mounted a torpedo attack against the rear half of the German line; Kronprinz spotted several unidentified destroyers in the darkness. Kronprinz held her fire, and she and the other battleships turned away to avoid torpedoes.[34] One torpedo, fired by the destroyer Obedient, exploded about 100 yd (91 m) behind Kronprinz, in the battleship's wake. Both Obedient and Faulknor reported a hit on Kronprinz, though she was undamaged by the near miss.[35] Heavy fire from the German battleships forced the British destroyers to withdraw.[36] The High Seas Fleet had managed to punch through the British light forces and subsequently reached Horns Reef by 04:00 on 1 June,[37] and Wilhelmshaven a few hours later. The I Squadron battleships took up defensive positions in the outer roadstead, while Kronprinz, Kaiser, Kaiserin, and Prinzregent Luitpold stood ready just outside the entrance to Wilhelmshaven.[38]

In the course of the battle, Kronprinz had fired 144 armor-piercing and semi-armor-piercing rounds from her main battery guns,[39] though the exact numbers of each are unknown.[40] The ship did not fire her secondary 15 cm or 8.8 cm guns during the entire engagement.[41] Of the four König-class ships, only Kronprinz escaped damage during the battle.[8][42]

Subsequent operations

On 18 August 1916, Kronprinz took part in an operation to bombard Sunderland.[8] Admiral Scheer attempted a repeat of the original 31 May plan; the two serviceable German battlecruisers—Moltke and Von der Tann—supported by three dreadnoughts, were to bombard the coastal town of Sunderland in an attempt to draw out and destroy Beatty's battlecruisers. The rest of the fleet, including Kronprinz, would trail behind and provide cover.[43] The British were aware of the German plans and sortied the Grand Fleet to meet them. By 14:35, Admiral Scheer had been warned of the Grand Fleet's approach and, unwilling to engage the whole of the Grand Fleet just eleven weeks after the decidedly close call at Jutland, turned his forces around and retreated to German ports.[44]

Kronprinz participated in two uneventful fleet operations, one a month prior on 16 July to the north of Helgoland, and one into the North Sea on 18–20 October.[8] Kronprinz and the rest of III Squadron were sent to the Baltic directly afterward for training, which lasted until 2 November.[45] Upon returning from the Baltic, Kronprinz and the rest of III Squadron were ordered to cover the retrieval of a pair of U-boats that were stranded on the Danish coast. On the return trip, on 5 November 1916, Kronprinz was torpedoed by the British submarine J1 near Horns Reef.[9] The torpedo struck the ship beneath the forward-most gun turret and allowed approximately 250 metric tons (250 long tons; 280 short tons) of water into the ship. Kronprinz maintained her speed and reached port. The following day she was placed in drydock at the Imperial Dockyard in Wilhelmshaven for repairs, which lasted from 6 November to 4 December.[46][47] During this period, Bernhard Rösing took command of the vessel.[10]

After returning to III Squadron, Kronprinz took part in squadron training in the Baltic before conducting defensive patrols in the German Bight. In early 1917, the ship became the flagship of the deputy commander of the squadron, at that time Rear Admiral Karl Seiferling. During training maneuvers on 5 March 1917, Kronprinz was accidentally rammed by her sister ship Grosser Kurfürst in the Heligoland Bight. The collision caused minor flooding in the area abreast of her forward superfiring turret; Kronprinz shipped some 600 t (590 long tons; 660 short tons) of water. She again went into the drydock in Wilhelmshaven, from 6 March to 14 May. On 11 September, Kronprinz was detached for training in the Baltic. She then joined the Special Unit for Operation Albion.[46][47]

Operation Albion

In early September 1917, following the German conquest of the Russian port of Riga, the German navy decided to eliminate the Russian naval forces that still held the Gulf of Riga. The Admiralstab (the Navy High Command) planned an operation to seize the Baltic island of Ösel, and specifically the Russian gun batteries on the Sworbe Peninsula.[48] On 18 September, the order was issued for a joint operation with the army to capture Ösel and Moon Islands; the primary naval component was to comprise the flagship, Moltke, along with III Battle Squadron of the High Seas Fleet. V Division included the four König-class ships, and was by this time augmented with the new battleship Bayern. VI Division consisted of the five Kaiser-class battleships. Along with nine light cruisers, three torpedo boat flotillas, and dozens of mine warfare ships, the entire force numbered some 300 ships, supported by over 100 aircraft and six zeppelins. The invasion force amounted to approximately 24,600 officers and enlisted men.[49] Opposing the Germans were the old Russian pre-dreadnoughts Slava and Tsesarevich, the armored cruisers Bayan, Admiral Makarov, and Diana, 26 destroyers, and several torpedo boats and gunboats. The garrison on Ösel numbered some 14,000 men.[50]

The operation began on 12 October; at 03:00 König anchored off Ösel in Tagga Bay and disembarked soldiers. By 05:50, König opened fire on Russian coastal artillery emplacements,[51] joined by Moltke, Bayern, and the other three König-class ships. Simultaneously, the Kaiser-class ships engaged the batteries on the Sworbe peninsula; the objective was to secure the channel between Moon and Dagö islands, which would block the only escape route of the Russian ships in the Gulf. Both Grosser Kurfürst and Bayern struck mines while maneuvering into their bombardment positions, with minimal damage to the former. Bayern was severely damaged, and had to be withdrawn to Kiel for repairs.[50] After the bombardment, Kronprinz departed the area for Putziger Wiek, where she refueled. The ship passed through Irben Strait on 16 October.[46]

On 16 October, it was decided to detach a portion of the invasion flotilla to clear the Russian naval forces in Moon Sound; these included the two Russian pre-dreadnoughts. To this end, Kronprinz and König, along with the cruisers Strassburg and Kolberg and a number of smaller vessels, were sent to engage the Russian battleships, leading to the Battle of Moon Sound. They arrived by the morning of 17 October, but a deep Russian minefield thwarted their progress. The Germans were surprised to discover that the 30.5 cm guns of the Russian battleships out-ranged their own 30.5 cm guns.[lower-alpha 6] The Russian ships managed to keep the range long enough to prevent the German battleships from being able to return fire, while still firing effectively on the German ships, and the Germans had to take several evasive maneuvers to avoid the Russian shells. By 10:00, the minesweepers had cleared a path through the minefield, and Kronprinz and König dashed into the bay. At around 10:15, Kronprinz opened fire on Tsarevitch and Bayan, and scored hits on both. König, meanwhile, dispatched Slava. The Russian vessels were hit dozens of times, until at 10:30 the Russian naval commander, Admiral Bakhirev, ordered their withdrawal.[52]

On 18 October, Kronprinz was slightly grounded, though the damage was not serious enough to necessitate withdrawal for repairs.[46] By 20 October, the fighting on the islands was winding down; Moon, Ösel, and Dagö were in German possession. The previous day, the Admiralstab had ordered the cessation of naval actions and the return of the dreadnoughts to the High Seas Fleet as soon as possible.[53] On the 26th, Kronprinz was more seriously grounded on the return trip to Kiel. She managed to reach Kiel on 2 November, and subsequently Wilhelmshaven. Repairs were effected from 24 November to 8 January 1918.[46]

Advance of 23 April 1918

On 27 January, the Kaiser directed that the ship be renamed Kronprinz Wilhelm in honor of the Crown Prince.[9] The ship was formally renamed on 15 June 1918, the 30th anniversary of the Kaiser's reign.[5] By this time, German light forces had begun raiding coal convoys between Britain and Norway, prompting the Grand Fleet to detach battleships to escort the shipments. The Germans were now presented with an opportunity for which they had been waiting the entire war: a portion of the numerically stronger Grand Fleet was separated and could be isolated and destroyed. Admiral Franz von Hipper, now the fleet commander, planned the operation: I Scouting Group with its accompanying light cruisers and destroyers would attack one of the large convoys while the rest of the High Seas Fleet would stand by, ready to attack the British battle squadron.[54]

At 05:00 on 23 April 1918, the German fleet, including Kronprinz, departed from the Schillig roadstead. Hipper ordered wireless transmissions be kept to a minimum, to prevent radio intercepts by British intelligence. At 06:10 the German battlecruisers had reached a position approximately 60 kilometers (37 mi) southwest of Bergen when Moltke lost her inner starboard propeller, which severely damaged the ship's engines. The crew effected temporary repairs that allowed the ship to steam at 4 kn (7.4 km/h), but it was decided to take the ship under tow. Despite this setback, Hipper continued northward. By 14:00, Hipper's force had crossed the convoy route several times but had found nothing. At 14:10, Hipper turned his ships southward. By 18:37, the German fleet had made it back to the defensive minefields surrounding their bases. It was later discovered that the convoy had left port a day later than expected by the German planning staff.[55][56]

Kronprinz saw no further major activity for the remainder of the war. During this period, Rear Admiral Ernst Goette and now-Rear Admiral Feldt flew their flags on the ship during their tenures as squadron deputy commander. The vessel went to the Imperial Dockyard in Kiel in mid-September for periodic maintenance.[56]

Fate

Kronprinz Wilhelm and her three sisters were to have taken part in a final fleet action at the end of October 1918, days before the Armistice was to take effect. The bulk of the High Seas Fleet was to have sortied from their base in Wilhelmshaven to engage the British Grand Fleet; Scheer—by now the Grand Admiral (Großadmiral) of the fleet—intended to inflict as much damage as possible on the British navy, in order to retain a better bargaining position for Germany, despite the expected casualties. Many of the war-weary sailors felt the operation would disrupt the peace process and prolong the war.[57] On the morning of 29 October 1918, the order was given to sail from Wilhelmshaven the following day. Starting on the night of 29 October, sailors on Thüringen and then on several other battleships, including Kronprinz Wilhelm, mutinied.[58] The unrest ultimately forced Hipper and Scheer to cancel the operation.[59] Informed of the situation, the Kaiser stated "I no longer have a navy."[60]

Following the capitulation of Germany in November 1918, most of the High Seas Fleet, under the command of Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter, were interned in the British naval base in Scapa Flow.[59] Prior to the departure of the German fleet, Admiral Adolf von Trotha made clear to Reuter that he could not allow the Allies to seize the ships, under any conditions.[61] The fleet rendezvoused with the British light cruiser Cardiff, which led the ships to the Allied fleet that was to escort the Germans to Scapa Flow. The massive flotilla consisted of some 370 British, American, and French warships.[62] Once the ships were interned, their guns were disabled through the removal of their breech blocks, and their crews were reduced to 200 officers and men.[63]

The fleet remained in captivity during the negotiations that ultimately produced the Treaty of Versailles. Reuter believed that the British intended to seize the German ships on 21 June 1919, which was the deadline for Germany to have signed the peace treaty. Unaware that the deadline had been extended to the 23rd, Reuter ordered the ships to be sunk at the next opportunity. On the morning of 21 June, the British fleet left Scapa Flow to conduct training maneuvers, and at 11:20 Reuter transmitted the order to his ships.[61] Kronprinz Wilhelm sank at 13:15;[5] The British guard detail panicked in their attempt to prevent the Germans from scuttling the ships;[64] British soldiers aboard a nearby drifter shot and killed a stoker from Kronprinz Wilhelm.[46] In total, the guards killed nine Germans and wounded twenty-one. The remaining crews, totaling some 1,860 officers and enlisted men, were imprisoned.[64]

Kronprinz Wilhelm was never raised for scrapping, unlike most of the other capital ships that were scuttled.[5] Kronprinz Wilhelm and two of her sisters had sunk in deeper water than the other capital ships, which made a salvage attempt more difficult. The outbreak of World War II in 1939 put a halt to all salvage operations, and after the war it was determined that salvaging the deeper wrecks was financially impractical.[65] The rights to future salvage operations on the wreck were sold to Britain in 1962.[5] The depth in which the three battleships sank insulated them from the radiation released by the use of atomic weapons. As a result, Kronprinz Wilhelm and her sisters are one of the few remaining sources of radiation-free steel. The ships have occasionally had steel removed for use in scientific devices.[65] Kronprinz Wilhelm and the other vessels on the bottom of Scapa Flow are a popular dive site, and are protected by a policy barring divers from recovering items from the wrecks.[66]

In 2017, marine archaeologists from the Orkney Research Centre for Archaeology conducted extensive surveys of Kronprinz Wilhelm and nine other wrecks in the area, including six other German and three British warships. The archaeologists mapped the wrecks with sonar and examined them with remotely operated underwater vehicles as part of an effort to determine how the wrecks are deteriorating.[67] The wreck lies between 12 and 38 m (39 and 125 ft) and remains a popular site for recreational scuba divers. Unusually for ships of this size, some of her main guns remain exposed.[68]

The wreck at some point came into the ownership of the firm Scapa Flow Salvage, which sold the rights to the vessel to Tommy Clark, a diving contractor, in 1981. Clark listed the wreck for sale on eBay with a "buy-it-now" price of £250,000, with the auction lasting until 28 June 2019. Three other wrecks—those of Markgraf, König, and the light cruiser Karlsruhe—all also owned by Clark, were also placed for sale.[69] The wrecks of Kronprinz Wilhelm and her two sisters ultimately sold for £25,500 apiece to a company from the Middle East, while Karlsruhe sold to a private buyer for £8,500.[70]

Notes

Footnotes

- "SMS" stands for "Seiner Majestät Schiff" (English: His Majesty's Ship).

- In Imperial German Navy gun nomenclature, "SK" (Schnelladekanone) denotes that the gun is quick loading, while the L/50 denotes the length of the gun. In this case, the L/50 gun is 50 calibers, meaning that the gun is 45 times as long as it is in bore diameter.[4]

- German warships were ordered under provisional names. For new additions to the fleet, they were given a single letter; for those ships intended to replace older or lost vessels, they were ordered as "Ersatz (name of the ship to be replaced)". See Gröner, p. 28.

- The Germans were on Central European Time, which is one hour ahead of UTC, the time zone commonly used in British works.

- The compass can be divided into 32 points, each corresponding to 11.25 degrees. A two-point turn to port would alter the ships' course by 22.5 degrees.

- The Russian ships had had their main battery turrets modified to allow elevation of the guns to 30°. This was much greater than the elevation of the German guns. See Halpern, p. 218.

Citations

- Herwig, p. 70.

- Gardiner & Gray, pp. 147–148.

- Gröner, p. 27.

- Grießmer, p. 177.

- Gröner, p. 28.

- Campbell "Germany 1906–1922", p. 36.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 168–169.

- Staff, p. 36.

- Preston, p. 80.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 168.

- Staff, p. 29.

- Tarrant, p. 53.

- Tarrant, p. 54.

- Tarrant, p. 286.

- Tarrant, pp. 94–95.

- Tarrant, pp. 100–101.

- Tarrant, p. 110.

- Campbell Jutland, p. 54.

- Campbell Jutland, p. 99.

- Campbell Jutland, p. 100.

- Campbell Jutland, p. 104.

- Campbell Jutland, pp. 116–117.

- Tarrant, p. 137.

- Tarrant, p. 138.

- Tarrant, p. 140.

- Campbell Jutland, p. 181.

- Campbell Jutland, p. 153.

- Tarrant, p. 169.

- Campbell Jutland, p. 201.

- Campbell Jutland, pp. 204–205.

- Campbell Jutland, p. 206.

- Tarrant, pp. 172–174.

- Campbell Jutland, p. 275.

- Campbell Jutland, pp. 298–299.

- Campbell Jutland, p. 299.

- Campbell Jutland, pp. 300–301.

- Tarrant, pp. 246–247.

- Campbell Jutland, p. 320.

- Campbell Jutland, p. 348.

- Campbell Jutland, p. 349.

- Campbell Jutland, p. 359.

- Campbell Jutland, p. 352.

- Massie, p. 682.

- Massie, p. 683.

- Staff, pp. 36–37.

- Staff, p. 37.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 169.

- Halpern, p. 213.

- Halpern, pp. 214–215.

- Halpern, p. 215.

- Staff, p. 31.

- Halpern, p. 218.

- Halpern, p. 219.

- Massie, pp. 747–748.

- Massie, p. 748.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 170.

- Tarrant, pp. 280–281.

- Tarrant, pp. 281–282.

- Tarrant, p. 282.

- Herwig, p. 252.

- Herwig, p. 256.

- Herwig, pp. 254–255.

- Herwig, p. 255.

- Herwig, p. 257.

- Butler, p. 229.

- Konstam, p. 187.

- Gannon.

- "SMS Kronprinz Wilhelm: Scapa Flow Wrecks". Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- "Scapa Flow: Sunken WW1 battleships up for sale on eBay". BBC News. 19 June 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- "Sunken WW1 Scapa Flow warships sold for £85,000 on eBay". BBC News. 9 July 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

References

- Butler, Daniel Allen (2006). Distant Victory: The Battle of Jutland and the Allied Triumph in the First World War. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-99073-2.

- Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-1-55821-759-1.

- Campbell, John (1987). "Germany 1906–1922". In Sturton, Ian (ed.). Conway's All the World's Battleships: 1906 to the Present. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 28–49. ISBN 978-0-85177-448-0.

- Gannon, Megan (4 August 2017). "Archaeologists Map Famed Shipwrecks and War Graves in Scotland". Livescience.com. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Grießmer, Axel (1999). Die Linienschiffe der Kaiserlichen Marine: 1906–1918; Konstruktionen zwischen Rüstungskonkurrenz und Flottengesetz [The Battleships of the Imperial Navy: 1906–1918; Constructions between Arms Competition and Fleet Laws] (in German). Bonn: Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7637-5985-9.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7.

- Herwig, Holger (1998) [1980]. "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert & Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe (Band 5) [The German Warships (Volume 5)] (in German). Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7822-0456-9.

- Konstam, Angus (2002). The History of Shipwrecks. New York: Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1-58574-620-0.

- Massie, Robert K. (2003). Castles of Steel. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-40878-5.

- Preston, Anthony (1972). Battleships of World War I: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Battleships of all Nations, 1914–1918. Harrisburg: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0211-9.

- Staff, Gary (2010). German Battleships: 1914–1918. 2: Kaiser, König And Bayern Classes. Oxford: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-468-8.

- Tarrant, V. E. (2001) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-304-35848-9.