Beekeeping in Australia

Beekeeping in Australia is a commercial industry with around 12,000 registered beekeepers owning over 520,000 hives by 2013-2014.[1] Most are to be found in the eastern states of Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania.

Beekeepers or apiarists, and their bees, produce honey, beeswax, package bees, queen bee pollen, royal jelly and provide pollination services for fruit trees and a variety of ground crops. These pollination services to agriculture alone are valued at between 8 and 19 billion Australian dollars a year.[2] The 30,000 tons or so of honey produced each year is worth around Aus$90 million.

Australia is the fourth largest honey exporting nation after China, Argentina and Mexico.[3] The high quality and unique flavours of Australian honey allows exporters to charge a premium price.

There are also beekeeping hobbyists in Australia who produce honey for home consumption or to be made into products, such as mead. A few are involved in domesticating native bees.

Pre-1788

Prior to European settlement Australian aboriginals consumed “sugarbag”, honey from native bees.[4] There are over 1,500 species of native bees. Some are social while others live alone. Most Australian native bees are either stingless or their stings are not generally dangerous to humans. However, native bees generally don't produce a large amount of honey.[5]

Introduction of European bees

The first imported honey bees to be successfully acclimatized in Australia were in seven hives that arrived on the convict transport ship Isabella which reached Sydney in March 1822.[6] Dr T.B. Wilson RN, surgeon-superintendent on the convict transport John that arrived Hobart on 28 January 1831[7] brought the first honey-bees to Tasmania.[8]

Later, other species were introduced from Italy, Yugoslavia, and North America.[9] The milder climate in Australia meant less honey had to be left in the hive to feed the bees through winter compared to Europe and North America.

Bee-farming develops

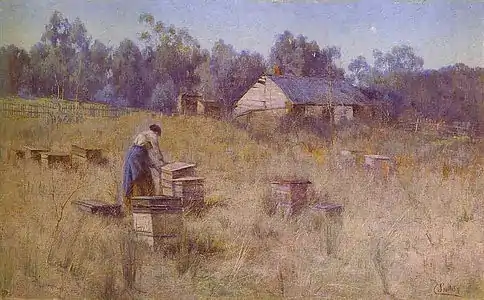

Australian farmers wishing to diversify and develop additional sources of income in the nineteenth century sometimes turned to bee-keeping as a side-line.[10] A row of gin cases on a rural property was a sign that bee-farming was in progress as they were frequently used as bee hives. Bee-keeping remained largely a part-time activity for farmers and people living on the outskirts of towns and cities till dedicated full-time beekeepers began to emerge.

The British author Anthony Trollope (1815-1882) visited Australia in 1871 and commented on the popularity of honey as a favourite food.

The wild bee of the country is not nearly so common as the much more generous and busier bee from Europe,- with which the bush many miles from the coast is already so plentifully filled that honey is a customary delicacy with all the settlers.[11]

The South Australian Beekeepers Society was established in 1884 and a beekeepers association was founded in Victoria in 1886.[12] The Victorian Apiarists Association started in 1900.[13]

In February 1903, Victorian bee-farmer Thomas Bolton (1863-1928) questioned the wisdom of clearing the forest in the Dunkeld area of the Western District. He said the blossom from the trees was annually converted by bees into honey worth £150 per square mile of forest. The land was being cleared to create grazing pastures for sheep which he claimed annually returned just £80 per square mile.[14] Bolton sent a test shipment of honey to China early in the 20th century. He reported, “The ships company thought so highly of his honey that empty cases were they only part of the consignment left when the ship reached port.”[15]

In 1921-22, Australia produced 7,370,790 pounds weight of honey.[16] Honey exports that year were worth £84,417. Beeswax was also exported.

Drawbacks to beekeeping in Australia include bushfires, frequent droughts and the tendency for beeswax to melt during very hot conditions. The distance from export markets is another issue. So too is the use of pesticides in agriculture.

The export of honey may have started in 1845 when an experimental shipment of honey and honeycomb was shipped from New South Wales to Britain in wooden casks.[17]

The production of honey and bees-wax fluctuates greatly and is determined by the flow of nectar from flora, particularly from the eucalypts, which varies greatly from year to year. Production in 1948-49 was 53,200,000 lbs (24,152,800 kg), a record high. The average returns from productive hives in 1958-59 was 103 lb. (46.8 kgs) of honey per hive and the average quantity of wax was 1.3 lb. (.59 kg) per productive hive.[18] Australia had 451,000 hives in 1958-59 of which 315,000 were regarded as productive. Total production during that period from all hives was 32,487,000 lbs (15,723,708 kg) with a gross value of £1,803,000. The amount of bees wax produced in 1958-59 was 417,000 lbs (189,318 kg) worth £105,000.[19]

Victoria has long been one of the main honey producing states. In 1971, there were 1,278 registered beekeepers in the state with 103,454 hives that produced 9,804,000 lbs of honey worth $984,000, plus 120,000 lbs of beeswax valued at $68,000.[20]

About 70% of Australian honey comes from nectar from native plants. Demand for pollination services for almonds and other crops is growing. Bee-brokers co-ordinate bee-keepers for pollination services for such crops.

The species most commonly used for bee keeping in Australia are European bees (Apis mellifera). Most commercial bee keepers have between 400 and 800 hives, but some large operators have up to 10,000.[21]

Australia produces 25,000 to 30,000 tonnes of honey annually.[22] Some is marketed as being from a single flowering species while other honey is produced from multiple types of flowering plants. Popular types of honey include Leatherwood, Blue Gum, Yellow Box and Karri, each named after the trees that produce the pollen and nectar gathered by the bees. The purity, taste and variety of Australian honey makes it popular in Asia and elsewhere.

Bushfires in the summer of 2019-20 caused massive losses of commercial honey bees, feral bees, native bees and other nectar-loving insects. Together they normally contribute about $14 billion to the Australian economy via the pollination of agricultural and broad-acre crops.[23] Canola and almonds are particularly dependant on honey bees. The fires also devastated some of the best nectar producing forests where bees forage. The reduced honey bee population is expected to take between three and twenty years to recover.

Diseases and parasites

Foul brood

In New South Wales in 1889 The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser uses a leaflet from the Beekeepers' Association of South Australia to outline how to recognise American foul brood (caused by Bacillus alvei) in a hive and how to treat it.[24] In South Australia, by 1891 an article in the South Australian Chronicle indicates that there was already an act in that state to attempt to control the spread of American foul brood.[25]

Small hive beetle

The small hive beetle was detected in Australia by 2003.[26]

Varroa Mite

The Varroa Mite (Varroa destructor) is a dangerous parasite that causes the honeybee population of hives to collapse. It is not yet present in Australia but it remains a threat.

Australian beekeepers

References

- Bee Aware website Industry Retrieved May 13, 2016

- Australian Honey Bee Industry Council, Monthly News, March 2018, honeybee.org.au

- vff.org.au

- Aussie Bee website Australian Stingless Bees Retrieved May 13, 2016

- Aussie Bee website Common Questions about Australian Native Bees Retrieved May 13, 2016

- Cumpston, J.S., (1977), Shipping arrivals & departures Sydney, 1788-1825, Canberra, Roebuck, p.132. ISBN 0909434158

- Nicholson, Ian Hawkins (1983), Shipping arrivals and departures Tasmania Vol 1, 1803-1833, Canberra, Roebuck, p.180. ISBN 0909434220

- The Hobart Town Courier, 10 August 1832, p.2

- Honeybee.org.au "The Wonderful Story of Australian Honey" Retrieved May 13, 2016

- Peel, Lynette (1974), Rural industry in the Port Phillip Region 1835-1880, Melbourne University Press, p.117. ISBN 0522840647

- Trollope, Anthony (1873), Australia and New Zealand, London, Tapman and Hall, p.190

- The South Australian Advertiser, 3 October 1884, p.9

- Bolton (1976), p.296

- "The Beekeper - Forest Destruction," The Australasian (Melbourne), 21 February 1903, p.10

- Bolton (1976), p.299

- The Illustrated Australian Encyclopaedia, vol 1, (1925) Sydney, Angus & Robertson, p.148

- “The Honey Trade,” Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, 29 August 1846, p.2

- Official year book of the Commonwealth of Australia, No.46, 1960, Canberra, Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics, p.1,001

- Commonwealth year book, 1960, p.1,002

- Victorian year book 1973, No.87, Melbourne, Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics, Victorian Office, p.902. ISBN 0642952965

- agrifutures.com.au, accessed 17 September 2019

- agrifutures.com.au, accessed 16 September 2019

- “Croppers to feel the yield sting from devastating bee losses,” The Land, 5 March 2020

- "Foul Brood" The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1871 - 1912) Sat 14 Dec 1889 Page 1305. Trove: National Library of Australia. Retrieved 9 March 2019

- "Foul Brood in Bees Deputation to the Commissioner of Crown Lands" South Australian Chronicle (Adelaide, SA : 1889 - 1895) Sat 18 Apr 1891 Page 13. Trove: National Library of Australia. Retrieved 9 March 2019

- Harman, Alan, “Small hive beetle in Australia,” Bee Culture, 131 (1) January 2003, p.59

Other published sources

- Bolton, Professor H.C., "Thomas Bolton: A pioneer bee-keeper in Victoria," The Victorian Historical Journal, Vol 47 (4) November 1976, 295-305

- Beekeeping in Victoria (1981), Melbourne, Victorian Department of Agriculture, 139p

- Honey flora of Victoria (1973), Melbourne, Victorian Department of Agriculture, 148p

- Klumpp, John, (2007), Australian stingless bees: A guide to Sugarbag Beekeeping, Earthing Enterprises. ISBN 9780975713815

- Rayment, Rayment (1914) [First published 1914]. Money in bees in Australasia: A practical treatise on the profitable management of the honey bee in Australasia, and a Special Section Dealing with the Nectariferous Value of Indigenous Flora (1st ed.). Whitcombe and Tombs Ltd. pp. 1–293. OCLC 762734838.

External links

- Beekeeper Digitised newspapers & Government Gazettes, Trove: National Library of Australia.

- Australian Beekeeping Guide (2014) Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation Publication No. 14/098

- Biosecurity Manual for Beekeepers Version 1.1 (2016) (Plant Health Australia and Australian Honey Bee Industry Council)

- Australian Honey Bee Industry Biosecurity Code of Practice (2014) Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Beekeeping in Australia. |