Beeswax

Beeswax (cera alba) is a natural wax produced by honey bees of the genus Apis. The wax is formed into scales by eight wax-producing glands in the abdominal segments of worker bees, which discard it in or at the hive. The hive workers collect and use it to form cells for honey storage and larval and pupal protection within the beehive. Chemically, beeswax consists mainly of esters of fatty acids and various long-chain alcohols.

Beeswax has been used since prehistory as the first plastic, as a lubricant and waterproofing agent, in lost wax casting of metals and glass, as a polish for wood and leather, for making candles, as an ingredient in cosmetics and as an artistic medium in encaustic painting.

Beeswax is edible, having similarly negligible toxicity to plant waxes, and is approved for food use in most countries and in the European Union under the E number E901.

Production

The wax is formed by worker bees, which secrete it from eight wax-producing mirror glands on the inner sides of the sternites (the ventral shield or plate of each segment of the body) on abdominal segments 4 to 7.[1] The sizes of these wax glands depend on the age of the worker, and after many daily flights, these glands gradually begin to atrophy.

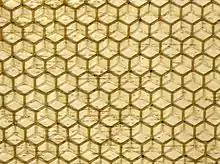

The new wax is initially glass-clear and colorless, becoming opaque after chewing and being contaminated with pollen by the hive worker bees, becoming progressively yellower or browner by incorporation of pollen oils and propolis. The wax scales are about three millimetres (0.12 in) across and 0.1 mm (0.0039 in) thick, and about 1100 are needed to make a gram of wax.[2] Worker bees use the beeswax to build honeycomb cells. For the wax-making bees to secrete wax, the ambient temperature in the hive must be 33 to 36 °C (91 to 97 °F).

The book, Beeswax Production, Harvesting, Processing and Products, suggests one kilogram (2.2 lb) of beeswax is sufficient to store 22 kg (49 lb) of honey.[3]:41 Another study estimated that one kilogram (2.2 lb) of wax can store 24 to 30 kg (53 to 66 lb) of honey.[4][5]

Honey in fat cells associated with wax glands is metabolized by bees into beeswax.[6] The amount of honey used by bees to produce wax has not been accurately determined, but according to Whitcomb's 1946 experiment, 6.66 to 8.80 kg (14.7 to 19.4 lb) of honey yields one kilogram (2.2 lb) of wax.[3]:35

Processing

When beekeepers extract the honey, they cut off the wax caps from each honeycomb cell with an uncapping knife or machine.

Beeswax may arise from such cappings, or from an old comb that is scrapped, or from the beekeeper removing unwanted burr comb and brace comb and suchlike. Its color varies from nearly white to brownish, but most often is a shade of yellow, depending on purity, the region, and the type of flowers gathered by the bees. The wax from the brood comb of the honey bee hive tends to be darker than wax from the honeycomb because impurities accumulate more quickly in the brood comb. Due to the impurities, the wax must be rendered before further use. The leftovers are called slumgum, and is derived from old breeding rubbish (pupa casings, cocoons, shed larva skíns, etc), bee droppings, propolis, and general rubbish.

The wax may be clarified further by heating in water. As with petroleum waxes, it may be softened by dilution with mineral oil or vegetable oil to make it more workable at room temperature.

Bees reworking old wax

When bees, needing food, uncap honey, they drop the removed cappings and let them fall to the bottom of the hive. It is known for bees to rework such an accumulation of fallen old cappings into strange formations.[7]

Physical characteristics

| Wax content type | Percentage |

| Hydrocarbons | 14% |

| Monoesters | 35% |

| Diesters | 14% |

| Triesters | 3% |

| Hydroxy monoesters | 4% |

| Hydroxy polyesters | 8% |

| Acid esters | 1% |

| Acid polyesters | 2% |

| Free fatty acids | 12% |

| Free fatty alcohols | 1% |

| Unidentified | 6% |

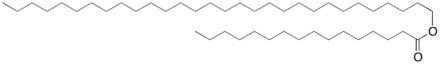

Beeswax is a fragrant solid at room temperature. The colors are light yellow, medium yellow, or dark brown and white. Beeswax is a tough wax formed from a mixture of several chemical compounds. An approximate chemical formula for beeswax is C15H31COOC30H61.[8] Its main constituents are palmitate, palmitoleate, and oleate esters of long-chain (30–32 carbons) aliphatic alcohols, with the ratio of triacontanyl palmitate CH3(CH2)29O-CO-(CH2)14CH3 to cerotic acid CH3(CH2)24COOH, the two principal constituents, being 6:1. Beeswax can be classified generally into European and Oriental types. The saponification value is lower (3–5) for European beeswax, and higher (8–9) for Oriental types.The analytical characterization can be done by high-temperature Gas Chromatography.[9]

Beeswax has a relatively low melting point range of 62 to 64 °C (144 to 147 °F). If beeswax is heated above 85 °C (185 °F) discoloration occurs. The flash point of beeswax is 204.4 °C (400 °F).[10]

When natural beeswax is cold, it is brittle, and its fracture is dry and granular. At room temperature (conventionally taken as about 20 °C (68 °F)), it is tenacious and it softens further at human body temperature (37 °C (99 °F)). The specific gravity of beeswax at 15 °C (59 °F) is from 0.958 to 0.975; that of melted beeswax at 98 to 99 °C (208.4 to 210.2 °F) (compared with water at 15.5 °C (59.9 °F)) is 0.9822.[11]

Uses

Candle-making has long involved the use of beeswax, which burns readily and cleanly, and this material was traditionally prescribed for the making of the Paschal candle or "Easter candle". Beeswax candles are purported to be superior to other wax candles, because they burn brighter and longer, do not bend, and burn "cleaner".[12] It is further recommended for the making of other candles used in the liturgy of the Roman Catholic Church.[13] Beeswax is also the candle constituent of choice in the Orthodox Church.[14][15]

Refined beeswax plays a prominent role in art materials both as a binder in encaustic paint and as a stabilizer in oil paint to add body.[16]

| Top five beeswax producers (2012, in tonnes) | |

|---|---|

| 23,000 | |

| 5,000 | |

| 4,700 | |

| 4,235 | |

| 3,063 | |

| World total | |

|

| |

Beeswax is an ingredient in surgical bone wax, which is used during surgery to control bleeding from bone surfaces; shoe polish and furniture polish can both use beeswax as a component, dissolved in turpentine or sometimes blended with linseed oil or tung oil; modeling waxes can also use beeswax as a component; pure beeswax can also be used as an organic surfboard wax.[18] Beeswax blended with pine rosin is used for waxing, and can serve as an adhesive to attach reed plates to the structure inside a squeezebox. It can also be used to make Cutler's resin, an adhesive used to glue handles onto cutlery knives. It is used in Eastern Europe in egg decoration; it is used for writing, via resist dyeing, on batik eggs (as in pysanky) and for making beaded eggs. Beeswax is used by percussionists to make a surface on tambourines for thumb rolls. It can also be used as a metal injection moulding binder component along with other polymeric binder materials.[19]

Beeswax was formerly used in the manufacture of phonograph cylinders. It may still be used to seal formal legal or royal decree and academic parchments such as placing an awarding stamp imprimatur of the university upon completion of postgraduate degrees.

Purified and bleached beeswax is used in the production of food, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals. The three main types of beeswax products are yellow, white, and beeswax absolute. Yellow beeswax is the crude product obtained from the honeycomb, white beeswax is bleached or filtered yellow beeswax, and beeswax absolute is yellow beeswax treated with alcohol. In food preparation, it is used as a coating for cheese; by sealing out the air, protection is given against spoilage (mold growth). Beeswax may also be used as a food additive E901, in small quantities acting as a glazing agent, which serves to prevent water loss, or used to provide surface protection for some fruits. Soft gelatin capsules and tablet coatings may also use E901. Beeswax is also a common ingredient of natural chewing gum. The wax monoesters in beeswax are poorly hydrolysed in the guts of humans and other mammals, so they have insignificant nutritional value.[20] Some birds, such as honeyguides, can digest beeswax.[21] Beeswax is the main diet of wax moth larvae.[22]

The use of beeswax in skin care and cosmetics has been increasing. A German study found beeswax to be superior to similar barrier creams (usually mineral oil-based creams such as petroleum jelly), when used according to its protocol.[23] Beeswax is used in lip balm, lip gloss, hand creams, salves, and moisturizers; and in cosmetics such as eye shadow, blush, and eye liner. Beeswax is also an important ingredient in moustache wax and hair pomades, which make hair look sleek and shiny.

In oil spill control, beeswax is processed to create Petroleum Remediation Product (PRP). It is used to absorb oil or petroleum-based pollutants from water.[24]

Historical uses

Beeswax was among the first plastics to be used, alongside other natural polymers such as gutta-percha, horn, tortoiseshell, and shellac. For thousands of years, beeswax has had a wide variety of applications; it has been found in the tombs of Egypt, in wrecked Viking ships, and in Roman ruins. Beeswax never goes bad and can be heated and reused. Historically, it has been used:

- As candles - the oldest intact beeswax candles north of the Alps were found in the Alamannic graveyard of Oberflacht, Germany, dating to 6th/7th century AD

- In the manufacture of cosmetics

- As a modelling material in the lost-wax casting process, or cire perdue[25]

- For wax tablets used for a variety of writing purposes

- In encaustic paintings such as the Fayum mummy portraits[26]

- In bow making

- To strengthen and preserve sewing thread, cordage, shoe laces, etc.

- As a component of sealing wax

- To strengthen and to forestall splitting and cracking of wind instrument reeds

- To form the mouthpieces of a didgeridoo, and the frets on the Philippine kutiyapi – a type of boat lute

- As a sealant or lubricant for bullets in cap and ball firearms

- To stabilize the military explosive Torpex – before being replaced by a petroleum-based product

- In producing Javanese batik[27]

- As an ancient form of dental tooth filling[28][29]

- As the joint filler in the slate bed of pool and billiard tables.

See also

References

- Sanford, M.T.; Dietz, A. (1976). "The fine structure of the wax gland of the honey bee (Apis mellifera L.)" (PDF). Apidologie. 7 (3): 197–207. doi:10.1051/apido:19760301.

- Brown, R, H. (1981) Beeswax (2nd edition) Bee Books New and Old, Burrowbridge, Somerset UK. ISBN 0-905652-15-0

- Beeswax Production, Harvesting, Processing and Products, Coggshall and Morse. Wicwas Press. 1984-06-01. ISBN 978-1878075062.

- Les Crowder (2012-08-31). Top-Bar Beekeeping: Organic Practices for Honeybee Health. Chelsea Green Publishing. ISBN 978-1603584616.

- Top-bar beekeeping in America Archived 2014-07-29 at the Wayback Machine.

- Collision, Clarence (31 March 2015). "A CLOSER LOOK: BEESWAX, WAX GLANDS". Bee Culture. beeculture.com. pp. 12–27. Retrieved 2020-06-16.

- Seeley, Thomas D. (2019-05-28). The Lives of Bees. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-18938-3.

- Umney, Nick; Shayne Rivers (2003). Conservation of Furniture. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 164.

- N. Limsathayourat, H.-U. Melchert: High-temperature capillary GLC of hydrocarbons, fatty-acid derivatives, cholesterol esters, wax esters and triglycerides in beeswax analysis. In: Fresenius’ Journal of Analytical Chemistry. 318, Nr. 6, 1984, S. 410–413, doi:10.1007/BF00533223.

- "MSDS for beeswax".. No reported autoignition temperature has been reported

- A Dictionary of Applied Chemistry, Vol. 5. Sir Edward Thorpe. Revised and enlarged edition. Longmans, Green, and Co., London, 1916. "Waxes, Animal and vegetable. Beeswax", p. 737

- Norman, Gary (2010). Honey Bee Hobbyist: The Care and Keeping of Bees. California, USA: BowTie Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-933958-94-1.

- 'Altar Candles", 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia

- , Use of Candles in the Orthodox Church

- Uwe Wolfmeier, Hans Schmidt, Franz-Leo Heinrichs, Georg Michalczyk, Wolfgang Payer, Wolfram Dietsche, Klaus Boehlke, Gerd Hohner, Josef Wildgruber "Waxes" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2002. doi:10.1002/14356007.a28_103.

- 1895-1979., Mayer, Ralph (1991). The artist's handbook of materials and techniques. Sheehan, Steven. (Fifth edition, revised and updated ed.). New York. ISBN 978-0670837014. OCLC 22178945.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Statistics from: Food And Agricultural Organization of United Nations: Economic And Social Department: The Statistical Division". UN Food and Agriculture Organization Corporate Statistical Database. Archived from the original on 2011-07-13.

- 'Raw Beeswax Uses" Archived 2013-11-06 at the Wayback Machine, MoreNature

- 'Metal Injection Molding Process (MIM)" Archived 2012-05-10 at the Wayback Machine, 2012 EngPedia

- Beeswax absorption and toxicity. Large amounts of such waxes in the diet pose theoretical toxicological problems for mammals.

- Downs, Colleen T; van Dyk, Robyn J; Iji, Paul (September 2002). "Wax digestion by the lesser honeyguide Indicator minor". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 133 (1): 125–134. doi:10.1016/s1095-6433(02)00130-7. PMID 12160878.

- Dadd, R.H. (December 1966). "Beeswax in the nutrition of the wax moth, Galleria mellonella (L.)". Journal of Insect Physiology. 12 (12): 1479–1492. doi:10.1016/0022-1910(66)90038-2.

-

Peter J. Frosch; Detlef Peiler; Veit Grunert; Beate Grunenberg (July 2003). "Wirksamkeit von Hautschutzprodukten im Vergleich zu Hautpflegeprodukten bei Zahntechnikern – eine kontrollierte Feldstudie. Efficacy of barrier creams in comparison to skincare products in dental laboratory technicians – a controlled trial". Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft (in German). 1 (7): 547–557. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0353.2003.03701.x. PMID 16295040.

CONCLUSIONS: The results demonstrate that the use of after-work moisturizers is highly beneficial and under the chosen study conditions even superior to barrier creams applied at work. This approach is more practical for many professions and may effectively reduce the frequency of irritant contact dermatitis.

- "Petroleum Remediation Product". spacefoundation.org. November 3, 2017. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- Congdon, L. O. K. (1985). "Water-Casting Concave-Convex Wax Models for Cire Perdue Bronze Mirrors". American Journal of Archaeology. 89 (3): 511–515. doi:10.2307/504365. JSTOR 504365.

- Egyptology online Archived 2007-08-08 at the Wayback Machine

- Ormeling, F. J. 1956. The Timor problem: a geographical interpretation of an underdeveloped island. Groningen and The Hague: J. B. Wolters and Martinus Nijhoff.

- "Oldest tooth filling may have been found – Light Years – CNN.com Blogs". Lightyears.blogs.cnn.com. Retrieved 2013-07-05.

- "Don't Use Your Teeth". Archived from the original on 2013-12-14. Retrieved 2013-12-13.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Beewax. |

| Look up beeswax in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- The chemistry of bees Joel Loveridge, School of Chemistry, University of Bristol, accessed November 2005