Benjamin Zephaniah

Benjamin Obadiah Iqbal Zephaniah (born 15 April 1958)[1] is a British writer, dub poet and Rastafarian. He was included in The Times list of Britain's top 50 post-war writers in 2008.[2]

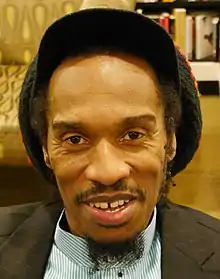

Benjamin Zephaniah | |

|---|---|

Benjamin Zephaniah, Waterstones, Piccadilly, London, December 2018 | |

| Born | Benjamin Obadiah Iqbal Zephaniah 15 April 1958 Handsworth, Birmingham, England |

| Occupation | Poet, playwright, author |

| Nationality | British |

| Genre | Poetry, teen fiction |

| Literary movement | Rastafari movement |

| Years active | 1980 – present |

| Spouse | Amina (m. 1990, divorced 2001) |

| Website | |

| benjaminzephaniah | |

Life and work

Zephaniah was born and raised in the Handsworth district of Birmingham,[3] which he has called the "Jamaican capital of Europe". He is the son of a Barbadian postman and a Jamaican nurse.[4][5] A dyslexic, he attended an approved school but left aged 13 unable to read or write.[5]

He writes that his poetry is strongly influenced by the music and poetry of Jamaica and what he calls "street politics". His first performance was in church when he was eleven, and by the age of fifteen, his poetry was already known among Handsworth's Afro-Caribbean and Asian communities.[6] He received a criminal record with the police as a young man and served a prison sentence for burglary.[5][7] Tired of the limitations of being a black poet communicating with black people only, he decided to expand his audience, and headed to London at the age of twenty-two.[4]

He became actively involved in a workers' co-operative in Stratford, London, which led to the publication of his first book of poetry, Pen Rhythm (Page One Books, 1980). Three editions were published. Zephaniah has said that his mission is to fight the dead image of poetry in academia, and to "take [it] everywhere" to people who do not read books, so he turned poetry readings into concert-like performances.[4]

His second collection of poetry, The Dread Affair: Collected Poems (1985), contained a number of poems attacking the British legal system. Rasta Time in Palestine (1990), an account of a visit to the Palestinian occupied territories, contained poetry and travelogue.

His 1982 album Rasta, which featured The Wailers' first recording since the death of Bob Marley as well as a tribute to the political prisoner (later to become South African president) Nelson Mandela, gained him international prestige[8] and topped the Yugoslavian pop charts.[6][8] It was because of this recording that he was introduced to Mandela, and in 1996, Mandela requested that Zephaniah host the president's Two Nations Concert at the Royal Albert Hall, London. Zephaniah was poet in residence at the chambers of Michael Mansfield QC, and sat in on the inquiry into Bloody Sunday and other cases, these experiences leading to his Too Black, Too Strong poetry collection (2001).[5] We Are Britain! (2002) is a collection of poems celebrating cultural diversity in Britain.

Zephaniah's first book of poetry for children, called Talking Turkeys, was reprinted after six weeks. In 1999 he wrote a novel for teenagers, Face, the first of four novels to date.

Zephaniah lived for many years in East London but in 2008 began dividing his time between Beijing and a village near Spalding, Lincolnshire.[9]

He was married for twelve years to Amina, a theatre administrator, whom he divorced in 2001.[10]

In 2011, Zephaniah accepted a year-long position as poet in residence at Keats House in Hampstead, London.

Zephaniah is a supporter of Aston Villa F.C. and is the patron for an Aston Villa supporters' website.[11]

In 2020, he appeared as a panellist on the BBC television show QI, on the episode "Roaming".

Views

Zephaniah is an honorary patron of The Vegan Society,[12] Viva! (Vegetarians' International Voice for Animals),[13] EVOLVE! Campaigns,[14] the anti-racism organisation Newham Monitoring Project with whom he made a video[15] in 2012 about the impact of Olympic policing on black communities, Tower Hamlets Summer University and is an animal rights advocate. In 2004, he wrote the foreword to Keith Mann's book From Dusk 'til Dawn: An insider's view of the growth of the Animal Liberation Movement, a book about the Animal Liberation Front. In August 2007, he announced that he would be launching the Animal Liberation Project, alongside People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals.[16] He became a vegan when he read poems about "shimmering fish floating in an underwater paradise, and birds flying free in the clear blue sky".

In 2016, Zephaniah curated We Are All Human, an exhibition at the Southbank Centre presented by the Koestler Trust which exhibited art works by prisoners, detainees and ex-offenders.[17]

The poet joined Amnesty International in speaking out against homophobia in Jamaica, saying: "For many years Jamaica was associated with freedom fighters and liberators, so it hurts when I see that the home of my parents is now associated with the persecution of people because of their sexual orientation."[18]

Zephaniah is a Rastafari.[19] He gave up smoking cannabis in his thirties.[20]

In 2003, Zephaniah was offered appointment as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire, but publicly rejected it.[21] In a subsequent article for The Guardian he elaborated upon his reaction to learning about being considered for the award and his reasons for rejecting it: "Me? I thought, OBE me? Up yours, I thought. I get angry when I hear that word 'empire'; it reminds me of slavery, it reminds of thousands of years of brutality, it reminds me of how my foremothers were raped and my forefathers brutalised...Benjamin Zephaniah OBE – no way Mr Blair, no way Mrs Queen. I am profoundly anti-empire."[22]

Zephaniah has spoken in favour of a British Republic and the dis-establishment of the crown.[23] In 2015 he called for Welsh and Cornish to be taught in English schools, saying "Hindi, Chinese and French are taught [in schools], so why not Welsh? And why not Cornish? They're part of our culture."[24]

Zephaniah self-identifies as an anarchist.[25] He appeared in literature to support changing the British electoral system from first-past-the-post to alternative vote for electing members of parliament to the House of Commons in the Alternative Vote referendum in 2011.[26] In a 2017 interview, commenting on the ongoing Brexit negotiations, Zephaniah stated that "For left-wing reasons, I think we should leave the EU but the way that we’re leaving is completely wrong".[27]

In December 2019, along with 42 other leading cultural figures, Zephaniah signed a letter endorsing the Labour Party under Jeremy Corbyn's leadership in the 2019 general election. The letter stated that "Labour's election manifesto under Jeremy Corbyn's leadership offers a transformative plan that prioritises the needs of people and the planet over private profit and the vested interests of a few."[28][29]

Zephaniah is a supporter of the Palestine Solidarity Campaign and has joined demonstrations calling for an end to the Israeli occupation of Palestinian lands, describing the activism as the "Anti Apartheid movement".[30][31]

Achievements

Zephaniah won the BBC Young Playwright's Award.[1] He has been awarded honorary doctorates by the University of North London (in 1998),[1] the University of Central England (in 1999), Staffordshire University (in 2001),[32] London South Bank University (in 2003), the University of Exeter and the University of Westminster (in 2006). On 17 July 2008 Zephaniah received an honorary doctorate from the University of Birmingham.[33] He was listed at 48 in The Times list of 50 greatest postwar writers.[2]

He has released several albums of original music.[34] He was awarded Best Original Song in the Hancocks 2008, Talkawhile Awards for Folk Music (as voted by members of Talkawhile.co.uk[35]) for his version of Tam Lyn Retold recorded with The Imagined Village. He collected the Award live at The Cambridge Folk Festival on 2 August 2008 and described himself as a "Rasta Folkie".[36]

Books

Poetry

- Pen Rhythm (1980)

- The Dread Affair: Collected Poems (1985) Arena

- City Psalms (1992) Bloodaxe Books

- Inna Liverpool (1992) AK Press

- Talking Turkeys (1994) Puffin Books

- Propa Propaganda (1996) Bloodaxe Books

- Funky Chickens (1997) Puffin

- School's Out: Poems Not for School (1997) AK Press

- Funky Turkeys (Audiobook) (1999) AB hntj

- White Comedy (Unknown)

- Wicked World! (2000) Puffin

- Too Black, Too Strong (2001) Bloodaxe Books

- The Little Book of Vegan Poems (2001) AK Press

- Reggae Head (Audiobook) 57 Productions

Novels

- Face (1999) Bloomsbury (published in children's and adult editions)

- Refugee Boy (2001) Bloomsbury

- Gangsta Rap (2004) Bloomsbury

- Teacher's Dead (2007) Bloomsbury

- Terror Kid (2014) Bloomsbury[37]

Children's books

- We are Britain (2002) Frances Lincoln

- Primary Rhyming Dictionary (2004) Chambers Harrap

- J is for Jamaica (2006) Frances Lincoln

- My Story (2011), Collins

- When I Grow Up (2011), Frances Lincoln

Other

- Kung Fu Trip (2011), Bloomsbury

- The Life And Rhymes of Benjamin Zephaniah (2018), Simon & Schuster[38]

Plays

- Playing the Right Tune (1985)

- Job Rocking (1987). Published in Black Plays: 2, ed. Yvonne Brewster, Methuen Drama, 1989.

- Delirium (1987)

- Streetwise (1990)

- Mickey Tekka (1991)

- Listen to Your Parents (included in Theatre Centre: Plays for Young People – Celebrating 50 Years of Theatre Centre (2003) Aurora Metro, also published by Longman, 2007)

- Face: The Play (with Richard Conlon)

Acting roles

- Didn't You Kill My Brother? (1987) – Rufus

- Farendj (1989) – Moses

- Dread Poets' Society (1992) – Andy Wilson

- Truth or Dairy (1994) – The Vegan Society (UK)

- Crucial Tales (1996) – Richard's father

- Making the Connection (2010) – Environment Films / The Vegan Society (UK)

- Peaky Blinders (2013–present) – Jeremiah Jesus

Discography

Albums

- Rasta (1982) Upright (reissued 1989) Workers Playtime (UK Indie #22)[39]

- Us An Dem (1990) Island

- Back to Roots (1995) Acid Jazz

- Belly of De Beast (1996) Ariwa

- Naked (2005) One Little Indian

- Naked & Mixed-Up (2006) One Little Indian (Benjamin Zephaniah Vs. Rodney-P)

- Revolutionary Minds (2017) Fane Productions

Singles, EPs

- Dub Ranting EP (1982) Radical Wallpaper

- "Big Boys Don't Make Girls Cry" 12-inch single (1984) Upright

- "Free South Africa" (1986)

- "Crisis" 12-inch single (1992) Workers Playtime

Guest appearances

- "Empire" (1995) Bomb the Bass with Zephaniah & Sinéad O'Connor

- Heading for the Door by Back to Base (2000) MPR Records

- Open Wide (2004) Dubioza kolektiv (C) & (P) Gramofon

- Rebel by Toddla T (2009) 1965 Records

- "Illegal" (2000) from "Himawari" by Swayzak

- "Theatricks" (2000) by Kinobe

See also

References

- Gregory, Andy (2002), International Who's Who in Popular Music 2002, Europa, p. 562. ISBN 1-85743-161-8.

- Benjamin Zephaniah, The 50 greatest postwar writers: 48 TimesOnline UK

- "Benjamin Zephaniah" Archived 3 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine, British Council. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

- "Biography" Archived 12 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine, BenjaminZephaniah.com. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

- Kellaway, Kate (2001) "Dread poet's society", The Guardian, 4 November 2001.

- Larkin, Colin (1998), The Virgin Encyclopedia of Reggae, Virgin Books, ISBN 0-7535-0242-9

- "ARTICLE: Interview with Raw Edge Magazine: Benjamin talks about how life in prison helped change his future as a poet. Archived 20 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine", Raw Edge magazine, issue 5, Autumn/Winter 1997.

- "Brighton Magazine – Benjamin Zephaniah: Well Read Rastafarian Poet Comes To Lewes". Magazine.brighton.co.uk.

- Lynn Barber interviews Benjamin Zephaniah, The Observer, 18 January 2009.

- Independent Arts and Books, 19 June 2009.

- "A Poet Called Benjamin Zephaniah". Benjaminzephaniah.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- "Honorary Patrons". Vegansociety.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- "Vegetarians International Voice for Animals". Viva!. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- "Evolve Campaigns". EVOLVE! Campaigns. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- "Benjamin Zephaniah – Put the Number in Your Phone". Newham Monitoring Project. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- Arkangel for Animal Liberation :: Online News Magazine Archived 17 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Bankes, Ariane. "Why we need to free art by prisoners from behind bars". Apollo Magazine. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- "Jamaica: Benjamin Zephaniah calls on Jamaicans everywhere to stand up against homophobia". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- Benjamin Zephaniah. "Has Snoop Dogg seen the Rastafari light, or is this just a midlife crisis?". The Guardian.

- Benjamin Zephaniah: ‘I don’t want to grow old alone’ The Guardian 6 May 2018

- Merope Mills, "Rasta poet publicly rejects his OBE", The Guardian, 27 November 2003. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- Zephaniah, Benjamin. "'Me? I thought, OBE me? Up yours, I thought'", The Guardian, 27 November 2003.

- "Statement of Principles". Republic. 29 April 2011. Archived from the original on 3 August 2009. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- "Benjamin Zephaniah calls for English schools to teach Welsh". BBC News. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- Benjamin Zephaniah, Why I Am an Anarchist, Dog Section Press, June 2019

- "Benjamin Zephaniah 'airbrushed from Yes to AV leaflets'". BBC News. 3 April 2011.

- "Benjamin Zephaniah Q&A: "My first racist attack was a brick in the back of the head"". New Statesman. 4 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Vote for hope and a decent future". The Guardian. 3 December 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- Proctor, Kate (3 December 2019). "Coogan and Klein lead cultural figures backing Corbyn and Labour". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- SagirSunday, Ceren; May 12; 2019 (12 May 2019). "Thousands in London call for an end to Israeli occupation of Palestine". Morning Star. Retrieved 14 July 2020.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Bratu, Alex (7 May 2019). "Birmingham poet Benjamin Zephaniah backs national demonstration for Palestine". I Am Birmingham. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- "Recipients of Honorary Awards". Staffordshire University. Archived from the original on 22 February 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- Collins, Tony (2008) "University honour for Doug Eliis",Birmingham Mail, 11 July 2008

- Perry, Kevin (7 March 2006). "Benjamin Zephaniah interview about Naked". London: The Beaver. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- "TalkAwhile UK Acoustic music forum". Talkawhile.co.uk. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- "Best Original Song". Talkawhile.co.uk. 3 August 2008. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- Zephaniah, Benjamin (2014). Terror Kid. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1471401770.

- Jonasson, Jonas (15 August 2017). "S&S scoops Zephaniah's memoir". The Bookseller. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- Lazell, Barry (1997) Indie Hits 1980–1989, Cherry Red Books, ISBN 0-9517206-9-4

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Benjamin Zephaniah |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Benjamin Zephaniah. |

- Official website

- Merope Mills, "Rasta poet publicly rejects his OBE", The Guardian, 27 November 2003.

- Benjamin Zephaniah – from The Black Presence in Britain

- Benjamin Zephaniah on Poetry, Politics and Revolution – video report by Democracy Now!