Bernoulli polynomials

In mathematics, the Bernoulli polynomials, named after Jacob Bernoulli, combine the Bernoulli numbers and binomial coefficients. They are used for series expansion of functions, and with the Euler–MacLaurin formula.

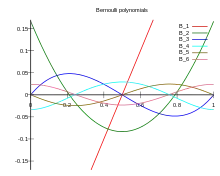

These polynomials occur in the study of many special functions and, in particular the Riemann zeta function and the Hurwitz zeta function. They are an Appell sequence (i.e. a Sheffer sequence for the ordinary derivative operator). For the Bernoulli polynomials, the number of crossings of the x-axis in the unit interval does not go up with the degree. In the limit of large degree, they approach, when appropriately scaled, the sine and cosine functions.

A similar set of polynomials, based on a generating function, is the family of Euler polynomials.

Representations

The Bernoulli polynomials Bn can be defined by a generating function. They also admit a variety of derived representations.

Generating functions

The generating function for the Bernoulli polynomials is

The generating function for the Euler polynomials is

Representation by a differential operator

The Bernoulli polynomials are also given by

where D = d/dx is differentiation with respect to x and the fraction is expanded as a formal power series. It follows that

cf. integrals below. By the same token, the Euler polynomials are given by

Representation by an integral operator

The Bernoulli polynomials are also the unique polynomials determined by

on polynomials f, simply amounts to

This can be used to produce the inversion formulae below.

Another explicit formula

An explicit formula for the Bernoulli polynomials is given by

That is similar to the series expression for the Hurwitz zeta function in the complex plane. Indeed, there is the relationship

where ζ(s, q) is the Hurwitz zeta function. The latter generalizes the Bernoulli polynomials, allowing for non-integer values of n.

The inner sum may be understood to be the nth forward difference of xm; that is,

where Δ is the forward difference operator. Thus, one may write

This formula may be derived from an identity appearing above as follows. Since the forward difference operator Δ equals

where D is differentiation with respect to x, we have, from the Mercator series,

As long as this operates on an mth-degree polynomial such as xm, one may let n go from 0 only up to m.

An integral representation for the Bernoulli polynomials is given by the Nörlund–Rice integral, which follows from the expression as a finite difference.

An explicit formula for the Euler polynomials is given by

The above follows analogously, using the fact that

Sums of pth powers

Using either the above integral representation of or the identity , we have

(assuming 00 = 1). See Faulhaber's formula for more on this.

The Bernoulli and Euler numbers

The Bernoulli numbers are given by

This definition gives for .

An alternate convention defines the Bernoulli numbers as

The two conventions differ only for since .

The Euler numbers are given by

Explicit expressions for low degrees

The first few Bernoulli polynomials are:

The first few Euler polynomials are:

Maximum and minimum

At higher n, the amount of variation in Bn(x) between x = 0 and x = 1 gets large. For instance,

which shows that the value at x = 0 (and at x = 1) is −3617/510 ≈ −7.09, while at x = 1/2, the value is 118518239/3342336 ≈ +7.09. D.H. Lehmer[1] showed that the maximum value of Bn(x) between 0 and 1 obeys

unless n is 2 modulo 4, in which case

(where is the Riemann zeta function), while the minimum obeys

unless n is 0 modulo 4, in which case

These limits are quite close to the actual maximum and minimum, and Lehmer gives more accurate limits as well.

Differences and derivatives

The Bernoulli and Euler polynomials obey many relations from umbral calculus:

(Δ is the forward difference operator). Also,

These polynomial sequences are Appell sequences:

Translations

These identities are also equivalent to saying that these polynomial sequences are Appell sequences. (Hermite polynomials are another example.)

Symmetries

Zhi-Wei Sun and Hao Pan [2] established the following surprising symmetry relation: If r + s + t = n and x + y + z = 1, then

where

Fourier series

The Fourier series of the Bernoulli polynomials is also a Dirichlet series, given by the expansion

Note the simple large n limit to suitably scaled trigonometric functions.

This is a special case of the analogous form for the Hurwitz zeta function

This expansion is valid only for 0 ≤ x ≤ 1 when n ≥ 2 and is valid for 0 < x < 1 when n = 1.

The Fourier series of the Euler polynomials may also be calculated. Defining the functions

and

for , the Euler polynomial has the Fourier series

and

Note that the and are odd and even, respectively:

and

They are related to the Legendre chi function as

and

Inversion

The Bernoulli and Euler polynomials may be inverted to express the monomial in terms of the polynomials.

Specifically, evidently from the above section on integral operators, it follows that

and

Relation to falling factorial

The Bernoulli polynomials may be expanded in terms of the falling factorial as

where and

denotes the Stirling number of the second kind. The above may be inverted to express the falling factorial in terms of the Bernoulli polynomials:

where

denotes the Stirling number of the first kind.

Multiplication theorems

The multiplication theorems were given by Joseph Ludwig Raabe in 1851:

For a natural number m≥1,

Integrals

Two definite integrals relating the Bernoulli and Euler polynomials to the Bernoulli and Euler numbers are:

Periodic Bernoulli polynomials

A periodic Bernoulli polynomial Pn(x) is a Bernoulli polynomial evaluated at the fractional part of the argument x. These functions are used to provide the remainder term in the Euler–Maclaurin formula relating sums to integrals. The first polynomial is a sawtooth function.

Strictly these functions are not polynomials at all and more properly should be termed the periodic Bernoulli functions, and P0(x) is not even a function, being the derivative of a sawtooth and so a Dirac comb.

The following properties are of interest, valid for all :

References

- D.H. Lehmer, "On the Maxima and Minima of Bernoulli Polynomials", American Mathematical Monthly, volume 47, pages 533–538 (1940)

- Zhi-Wei Sun; Hao Pan (2006). "Identities concerning Bernoulli and Euler polynomials". Acta Arithmetica. 125: 21–39. arXiv:math/0409035. Bibcode:2006AcAri.125...21S. doi:10.4064/aa125-1-3.

- Milton Abramowitz and Irene A. Stegun, eds. Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables, (1972) Dover, New York. (See Chapter 23)

- Apostol, Tom M. (1976), Introduction to analytic number theory, Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics, New York-Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-90163-3, MR 0434929, Zbl 0335.10001 (See chapter 12.11)

- Dilcher, K. (2010), "Bernoulli and Euler Polynomials", in Olver, Frank W. J.; Lozier, Daniel M.; Boisvert, Ronald F.; Clark, Charles W. (eds.), NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-19225-5, MR 2723248

- Cvijović, Djurdje; Klinowski, Jacek (1995). "New formulae for the Bernoulli and Euler polynomials at rational arguments". Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society. 123: 1527–1535. doi:10.2307/2161144.

- Guillera, Jesus; Sondow, Jonathan (2008). "Double integrals and infinite products for some classical constants via analytic continuations of Lerch's transcendent". The Ramanujan Journal. 16 (3): 247–270. arXiv:math.NT/0506319. doi:10.1007/s11139-007-9102-0. (Reviews relationship to the Hurwitz zeta function and Lerch transcendent.)

- Hugh L. Montgomery; Robert C. Vaughan (2007). Multiplicative number theory I. Classical theory. Cambridge tracts in advanced mathematics. 97. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. pp. 495–519. ISBN 0-521-84903-9.