Betar (fortress)

Betar fortress (Hebrew: בֵּיתַּר) was an ancient, terraced farming village in the Judean highlands.[1][2][3] The Betar fortress was the last standing Jewish fortress in the Bar Kokhba revolt of the 2nd century CE, destroyed by the Roman army of Emperor Hadrian in the year 135.

Walls of the Betar fortress. | |

Shown within the West Bank | |

| Location | West Bank |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 31.73°N 35.135556°E |

The site of historic Betar (also spelled Beitar or Bethar), next to the modern Palestinian village of Battir, southwest of Jerusalem, is known as Khirbet al-Yahud in Arabic (meaning "ruin of the Jews"). Today, the Israeli settlement and city Beitar Illit is also located nearby.

Etymology

Bet tar in ancient Hebrew means the place of the blade. Based on the variant spelling found in the Jerusalem Talmud (Codex Leiden), where the place name is written בֵּיתתֹּר,[4] the name may have simply been a contraction of two words: בית + תר, 'bet + tor', meaning, "the house of a dove."

History and archaeology

Early mentions

The origins of Betar are likely in the Iron Age Kingdom of Judea. It is not mentioned in the canonical Hebrew Bible, but is added in the Septuagint as one of the cities of the Tribe of Judah.

The location produced archaeological finds of pottery beginning from 8th century BCE and until late period of the Kingdom of Judah and again from early Roman period. In the early second century the town was a major stronghold and urban center in the Bethlehem area.

Bar Kokhba revolt

| Siege of Betar | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Fourth Phase of Bar Kokhba Revolt | |||||||

Fortifications of ancient Betar | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Jews | Roman Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Simon Bar Kokhba | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Legio V[5] Legio XI[5] | |||||||

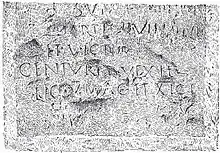

The city was the stronghold of Bar Kokhba, the leader of the Jewish Revolt against Roman occupation and took place in the days of Emperor Hadrian. After losing many of their strongholds, Bar Kokhba and the remnants of his army withdrew to the fortress of Betar, which subsequently came under siege in the summer of 135. Based on an inscription found there, the Legio V Macedonica and Legio XI Claudia have taken part in the siege.[6] A stone inscription bearing Latin characters and discovered near the city shows that the Fifth Macedonian Legion and the Eleventh Claudian Legion took part in the siege.[5]

Aftermath

The destruction of Betar in 135 put an end to the Jewish–Roman wars against Rome, and effectively quashed any Jewish hopes for self-governance in that period. Following the Fall of Betar, the Romans went on a systematic campaign of wiping out the remaining Judean villages, and hunting down refugees and the remaining rebels, with the last pockets of resistance being eliminated by the spring of 136.[7]

Talmud narrative and Jewish tradition

According to the Jerusalem Talmud, also known as the Palestinian Talmud, Betar remained a thriving town fifty-two years after the destruction of the Second Temple, until it came to its demise.[8]

Siege

According to the Jerusalem Talmud, the city was besieged for three and a half years before it finally fell (Jerusalem Talmud, Taanit 4:5 [24a]). According to Jewish tradition, the fortress was breached and destroyed on the fast of Tisha B'av, in the year 135, on the ninth day of the lunar month Av, a day of mourning for the destruction of the First and the Second Jewish Temple. Earlier, when the Roman army had circumvallated the city (from Latin, circum- + vallum, round-about + rampart), some sixty men of Israel went down and tried to make a breach in the Roman rampart, but to no avail. When they had not returned and were assumed as dead, the Sages of Israel permitted their wives to remarry, even though their husbands' bodies had not been retrieved.[9]

Massacre

The massacre perpetrated against all defenders, including the children who were found in the city, is described by the Palestinian Talmud.[10]

The Jerusalem Talmud relates that the number of dead in Betar was enormous, that the Romans "went on killing until their horses were submerged in blood to their nostrils."[11] The Romans killed all the defenders except for one Jewish youth whose life was spared, viz. Simeon ben Gamliel.[12]

Hadrian had prohibited the burial of the dead, and so all the bodies remained above ground. According to Jewish legend, they miraculously did not decompose.[13] Many years later Hadrian's successor, Antoninus (Pius), allowed the dead to be afforded a decent burial.

Rabbinical explanation

Rabbinical literature ascribes the defeat to Bar Kokhba killing his maternal uncle, Rabbi Elazar Hamudaʻi, after suspecting him of collaborating with the enemy, thereby forfeiting Divine protection.[14]

Sources

Accounts of the Fall of Betar in Talmudic and Midrashic writings reflect and amplify its importance in the Jewish psyche and oral tradition in the subsequent period. The best known is from the Babylonian Talmud, Gittin 57a-58a:

Rabbi Yohanan has related the following account of the massacre:[15] "The brains of three-hundred children were found upon one stone, along with three-hundred baskets of what remained of phylacteries (Hebrew: tefillin) were found in Betar, each and every one of which had the capacity to hold three measures (three seahs, or what is equivalent to about 28 liters). If you should come to take [all of them] into account, you would find that they amounted to three-hundred measures." Rabban [Shimon] Gamliel said: "Five-hundred schools were in Betar, while the smallest of them wasn't less than three-hundred children. They used to say, 'If the enemy should ever come upon us, with these styli [used in pointing at the letters of sacred writ] we'll go forth and stab them.' But since iniquities had caused [their fall], the enemy came in and wrapped up each and every child in his own book and burnt them together, and no one remained except me."

Legacy

Judaic religion

The fouth blessing that is said by Israel in the Grace over meals is said to have been enacted by the Sages of Israel in recognition of the dead at Betar who, although not afforded proper burial, their bodies did not putrefy and were, at last, brought to burial.[16]

Revisionist and Religious Zionism

The name of the Revisionist Zionist youth movement Betar[17] (בית"ר) refers to both the last Jewish fort to fall in the Bar Kokhba revolt, and to the slightly altered abbreviation of the Hebrew phrase "Berit Trumpeldor"[18] or "Brit Yosef Trumpeldor" (ברית יוסף תרומפלדור), lit. 'Joseph Trumpeldor Alliance'.[17]

The village of Mevo Betar was established on 24 April 1950 by native Israelis and immigrants from Argentina who were members of the Beitar movement, including Matityahu Drobles, later a member of the Knesset.[19] It was founded in the vicinity of the Betar fortress location, around a kilometre from the Green Line, which gave it the character of an exposed border settlement until the Six-Day War.

Beitar Illit, lit. Upper Beitar, is named after the ancient Jewish city of Betar, whose ruins lie 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) away. It was established by a small group of young families from the religious Zionist yeshiva of Machon Meir. The first residents settled in 1990.[20]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Betar (fortress). |

- David Ussishkin, "Soundings in Betar, Bar-Kochba's Last Stronghold"

- D. Ussishkin, Archaeological Soundings at Betar, Bar-Kochba's Last Stronghold, Tel Aviv 20, 1993, pp. 66-97.

- K. Singer, Pottery of the Early Roman Period from Betar, Tel Aviv 20, 1993, pp. 98-103.

- Jehiel ben Jekuthiel, ed. (1975). Talmud Yerushalmi (Codex Leiden, Scal. 3) (in Hebrew). 2. Makor Publishing Ltd. p. 644. OCLC 829454181.

- C. Clermont-Ganneau, Archaeological Researches in Palestine during the Years 1873–74, London 1899, pp. 263-270.

- Charles Clermont-Ganneau, Archaeological Researches in Palestine during the Years 1873–1874, London 1899, pp. 463-470

- Mohr Siebek et al. Edited by Peter Schäfer. The Bar Kokhba War reconsidered. 2003. P160. "Thus it is very likely that the revolt ended only in early 136."

- Jerusalem Talmud (Ta'anit 4:5 [24b])

- Tosefta (Yevamot 14:8)

- Palestinian Talmud, Taanit 4:5 (24a); Midrash Rabba (Lamentations Rabba 2:5).

- Ta'anit 4:5

- Palestinian Talmud, Taanit 4:5 (24a–b)

- Burial at Betar, blog.

- Jerusalem Talmud Ta'anit iv. 68d; Lamentations Rabbah ii. 2

- Midrash Rabba (Lamentations Rabba 2:5)

- Babylonian Talmud, Berakhot 48b

- "Youth Movements: Betar". Centenary of Zionism: 1897–1997. Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 4 August 1998. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- Shavit, Yaakov (1988). Jabotinsky and the Revisionist Movement 1925–1948. Frank Cass. p. 383.

- About Mevo Beitar

- Tzoren, Moshe Michael. "Some Talk Peace, Others Live It". Hamodia Israel News, November 21, 2018, pp. A18-A19.

Further reading

- Berenbaum, Michael; Skolnik, Fred, eds. (2007). "Bethar (Betar)". Encyclopaedia Judaica. Quoting from Gibson, Shimon. Encyclopaedia Hebraica (2 ed.). 3 (2 ed.). Thomson Gale. pp. 527–528. ISBN 978-0-02-865931-2.

- Ussishkin, David, "Archaeological Soundings at Betar, Bar-Kochba's Last Stronghold", in: Tel Aviv. Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University 20 (1993) 66ff.

External links

- Survey of Western Palestine, 1880 Map, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons Coordinates for Bittir (Khurbet el Yehudi): East longitude, 35.08; North latitude, 31.43

- Shimon Gibson (2006), Bethar, Encyclopedia Judaica, based on Encyclopedia Hebraica

- Prof. David Ussishkin, Soundings in Betar, Bar-Kochba's Last Stronghold.

- Other Midrashic sources can be seen here.