Knesset

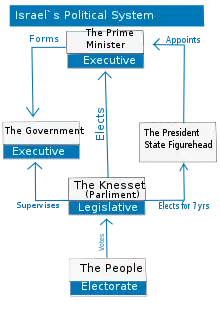

The Knesset (Hebrew: הַכְּנֶסֶת [ha ˈkneset] (![]() listen); lit. "gathering"[1] or "assembly") is the unicameral national legislature of Israel. As the legislative branch of the Israeli government, the Knesset passes all laws, elects the president and prime minister (although the latter is ceremonially appointed by the President), approves the cabinet, and supervises the work of the government. In addition, the Knesset elects the state comptroller. It also has the power to waive the immunity of its members, remove the president and the state comptroller from office, dissolve the government in a constructive vote of no confidence, and to dissolve itself and call new elections. The prime minister may also dissolve the Knesset. However, until an election is completed, the Knesset maintains authority in its current composition.[2] The Knesset is located in Givat Ram, Western Jerusalem. The Knesset was elected on 2 March 2020.[3] On 23 December 2020, the Knesset officially dissolved after a failure to come to a budget agreement and will not be restored until a new election is held.[4]

listen); lit. "gathering"[1] or "assembly") is the unicameral national legislature of Israel. As the legislative branch of the Israeli government, the Knesset passes all laws, elects the president and prime minister (although the latter is ceremonially appointed by the President), approves the cabinet, and supervises the work of the government. In addition, the Knesset elects the state comptroller. It also has the power to waive the immunity of its members, remove the president and the state comptroller from office, dissolve the government in a constructive vote of no confidence, and to dissolve itself and call new elections. The prime minister may also dissolve the Knesset. However, until an election is completed, the Knesset maintains authority in its current composition.[2] The Knesset is located in Givat Ram, Western Jerusalem. The Knesset was elected on 2 March 2020.[3] On 23 December 2020, the Knesset officially dissolved after a failure to come to a budget agreement and will not be restored until a new election is held.[4]

The Knesset הכנסת HaKnesset | |

|---|---|

| 23rd Knesset | |

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Leadership | |

Speaker | |

| Structure | |

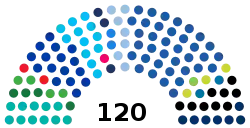

| Seats | 120 |

| |

Political groups | Caretaker government (67)

Opposition (53)

|

| Elections | |

| Party-list proportional representation D'Hondt method | |

Last election | 2 March 2020 |

Next election | 23 March 2021 |

| Meeting place | |

.JPG.webp) | |

| Knesset, Givat Ram, West Jerusalem, Israel | |

| Website | |

| Official website | |

| Part of a series on |

| Jerusalem |

|---|

-Aerial-Temple_Mount-(south_exposure).jpg.webp) |

| Sieges |

| Places |

| Political status |

| Other topics |

Name

The term "Knesset" is derived from the ancient Knesset HaGdola (Hebrew: כְּנֶסֶת הַגְּדוֹלָה) or "Great Assembly", which according to Jewish tradition was an assembly of 120 scribes, sages, and prophets, in the period from the end of the Biblical prophets to the time of the development of Rabbinic Judaism – about two centuries ending c. 200 BCE.[5] There is, however, no organisational continuity and aside from the number of members, there is little similarity, as the ancient Knesset was a religious, completely unelected body.

Members

Members of the Knesset are known in Hebrew as חֲבֵר הַכְּנֶסֶת (Haver HaKnesset), if male, or חַבְרַת הַכְּנֶסֶת (Havrat HaKnesset), if female.

Role in Israeli government

As the legislative branch of the Israeli government, the Knesset passes all laws, elects the president, approves the cabinet, and supervises the work of the government through its committees. It also has the power to waive the immunity of its members, remove the President and the State Comptroller from office, and to dissolve itself and call new elections.

The Knesset has de jure parliamentary supremacy, and can pass any law by a simple majority, even one that might arguably conflict with the Basic Laws of Israel, unless the basic law includes specific conditions for its modification; in accordance with a plan adopted in 1950, the Basic Laws can be adopted and amended by the Knesset, acting in its capacity as a Constituent Assembly.[6] The Knesset itself is regulated by a Basic Law called "Basic Law: the Knesset".

In addition to the absence of a formal constitution, and with no Basic Law thus far being adopted which formally grants a power of judicial review to the judiciary, the Supreme Court of Israel has since the early 1990s asserted its authority, when sitting as the High Court of Justice, to invalidate provisions of Knesset laws it has found to be inconsistent with Basic Law.[6] The Knesset is presided over by a Speaker and a Deputy Speaker.

Committees

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Israel |

|

|

The Knesset is divided into committees, which amend bills on various appropriate subjects. Committee chairpersons are chosen by their members, on recommendation of the House Committee, and their factional composition represents that of the Knesset itself. Committees may elect sub-committees and delegate powers to them, or establish joint committees for issues concerning more than one committee. To further their deliberations, they invite government ministers, senior officials, and experts in the matter being discussed. Committees may request explanations and information from any relevant ministers in any matter within their competence, and the ministers or persons appointed by them must provide the explanation or information requested.[2]

There are four types of committees in the Knesset. Permanent committees amend proposed legislation dealing with their area of expertise, and may initiate legislation. However, such legislation may only deal with Basic Laws and laws dealing with the Knesset, elections to the Knesset, Knesset members, or the State Comptroller. Special committees function in a similar manner to permanent committees, but are appointed to deal with particular manners at hand, and can be dissolved or turned into permanent committees. Parliamentary inquiry committees are appointed by the plenum to deal with issues viewed as having special national importance. In addition, there are two types of committees that convene only when needed: the Interpretations Committee, made up of the Speaker and eight members chosen by the House Committee, deals with appeals against the interpretation given by the Speaker during a sitting of the plenum to the Knesset rules of procedure or precedents, and Public Committees, established to deal with issues that are connected to the Knesset.[7][8]

Permanent committees:

- House Committee

- Finance Committee

- Economic Affairs Committee

- Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee

- Interior and Environment Committee

- Immigration, Absorption, and Diaspora Affairs Committee

- Education, Culture, and Sports Committee

- Constitution, Law, and Justice Committee

- Labour, Welfare, and Health Committee

- Science and Technology Committee

- State Control Committee

- Committee on the Status of Women

Special committees:

- Committee on Drug Abuse

- Committee on the Rights of the Child

- Committee on Foreign Workers

- Israeli Central Elections Committee

- Public Petitions Committee

The other committees are the Arrangements Committee and the Ethics Committee. The Ethics Committee is responsible for jurisdiction over Knesset members who violate the rules of ethics of the Knesset, or involved in illegal activities outside the Knesset. Within the framework of responsibility, the Ethics Committee may place various sanctions on a member, but is not allowed to restrict a members' right to vote. The Arrangements Committee proposes the makeup of the permanent committees following each election, as well as suggesting committee chairs, lays down the sitting arrangements of political parties in the Knesset, and the distribution of rooms in the Knesset building to members and parties.[9]

Caucuses

Knesset members often join together in formal or informal groups known as "lobbies" or "caucuses", to advocate for a particular topic. There are hundreds of such caucuses in the Knesset. The Knesset Christian Allies Caucus and the Knesset Land of Israel Caucus are two of the largest and most active caucuses.[10][11]

Size

The Knesset numbers 120 members, after the size of the Great Assembly. The subject of Knesset membership has often been a cause for proposed reforms. In 1996, then-Justice Minister Yossi Beilin, backed the ultimately unsuccessful institution of the so-called "Norwegian law", which would require appointed members of the cabinet to resign their seats in the Knesset and allow other members of their parties to take their positions while they serve in the cabinet; this would have resulted in more active members of the legislature being present in regular sessions and committee meetings. This proposed law has also been favoured by other politicians, including Benjamin Netanyahu.[12]

Elections

The 120 members of the Knesset (MKs)[13] are popularly elected from a single nationwide electoral district to concurrent four-year terms, subject to calls for early elections (which are quite common). All Israeli citizens 18 years or older may vote in legislative elections, which are conducted by secret ballot.

Knesset seats are allocated among the various parties using the D'Hondt method of party list proportional representation. A party or electoral alliance must pass the election threshold of 3.25%[14] of the overall vote to be allocated a Knesset seat. Parties select their candidates using a closed list. Thus, voters select the party of their choice, not any specific candidate.

The electoral threshold was previously set at 1% from 1949 to 1992, then 1.5% from 1992 to 2003, and then 2% until March 2014 when the current threshold of 3.25% was passed (effective with elections for the 20th Knesset).[15] As a result of the low threshold, a typical Knesset has 10 or more factions represented. With so many parties, it is nearly impossible for one party or faction to govern alone, let alone win a majority. No party or faction has ever won the 61 seats necessary for a majority; the closest being the 56 seats won by the Alignment in the 1969 elections (the Alignment had briefly held 63 seats going into the 1969 elections after being formed shortly beforehand by the merger of several parties, the only occasion on which any party or faction has ever held a majority). Every Israeli government has been a coalition of two or more parties.

After an election, the president meets with the leaders of every party that won Knesset seats and asks them to recommend which party leader should form the government. The president then nominates the party leader who is most likely to command the support of a majority in the Knesset (though not necessarily the leader of the largest party/faction in the chamber). The prime minister-designate has 42 days to put together a viable coalition (extensions can be granted and often are), and then must win a vote of confidence in the Knesset before taking office.

Current composition

The table below lists the parliamentary factions represented in the 23rd Knesset.

Functioning

Despite numerous motions of no confidence being tabled in the Knesset, a government has only been defeated by one once,[16] when Yitzhak Shamir's government was brought down on 15 March 1990 as part of a plot that became known as "the dirty trick" (Hebrew: התרגיל המסריח, HaTargil HaMasriaḥ, lit. "the stinking trick").

However, several governments have resigned as a result of no-confidence motions, even when they were not defeated. These include the fifth government, which fell after Prime Minister Moshe Sharett resigned in June 1955 following the abstention of the General Zionists (part of the governing coalition) during a vote of no-confidence;[17] the ninth government, which fell after Prime Minister Ben-Gurion resigned in January 1961 over a motion of no-confidence on the Lavon Affair;[18] and the seventeenth government, which resigned in December 1976 after the National Religious Party (part of the governing coalition) abstained in a motion of no-confidence against the government.

History

The Knesset first convened on 14 February 1949, following the 20 January elections, replacing the Provisional State Council which acted as Israel's official legislature from its date of independence on 14 May 1948 and succeeding the Assembly of Representatives that had functioned as the Jewish community's representative body during the Mandate era.

The Knesset compound sits on a hilltop in western Jerusalem in a district known as Sheikh Badr before the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, now Givat Ram. The main building was financed by James de Rothschild as a gift to the State of Israel in his will and was completed in 1966. It was built on land leased from the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem.[19] Over the years, significant additions to the structure were constructed, however, these were built at levels below and behind the main 1966 structure as not to detract from the original assembly building's appearance.

Before the construction of its permanent home, the Knesset met in the Jewish Agency building in Jerusalem, the Kessem Cinema building in Tel Aviv and the Froumine building in Jerusalem.[20]

Location and construction timeline

- 14 February 1949: First meeting of the Constituent Assembly, Jewish Agency, Jerusalem

- 8 March 1949 – 14 December 1949: Kessem Cinema in Tel Aviv (the Opera Tower, Migdal HaOpera, is situated there today)

- 26 December 1949 – 8 March 1950: Jewish Agency, Jerusalem

- 13 March 1950: Froumine Building, King George Street, Jerusalem.

- 1950–1955: Israeli government holds architectural competitions for the permanent Knesset building. Ossip Klarwein's original design won the competition

- 1955: Government approves plans to build the Knesset in its current location

- 1957: James de Rothschild informs Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion of his desire to finance the construction of the building

- 14 October 1958: Cornerstone-laying for new Knesset building

- 31 August 1966: Dedication of new building (during the sixth Knesset)

- 1981: Construction of new wing begins

- 1992: New wing opens

- 2001: Construction starts on a large new wing that essentially doubles the overall floorspace of the Knesset compound.

- 2007: New large wing opens

Knesset assemblies

Each Knesset session is known by its election number. Thus the Knesset elected by Israel's first election in 1949 is known as the First Knesset. The current Knesset, elected in 2020, is the Twenty-third Knesset.

- First Knesset (1949–1951)

- Second Knesset (1951–1955)

- Third Knesset (1955–1959)

- Fourth Knesset (1959–1961)

- Fifth Knesset (1961–1965)

- Sixth Knesset (1965–1969)

- Seventh Knesset (1969–1974)

- Eighth Knesset (1974–1977)

- Ninth Knesset (1977–1981)

- Tenth Knesset (1981–1984)

- Eleventh Knesset (1984–1988)

- Twelfth Knesset (1988–1992)

- Thirteenth Knesset (1992–1996)

- Fourteenth Knesset (1996–1999)

- Fifteenth Knesset (1999–2003)

- Sixteenth Knesset (2003–2006)

- Seventeenth Knesset (2006–2009)

- Eighteenth Knesset (2009–2013)

- Nineteenth Knesset (2013–2015)

- Twentieth Knesset (2015–2019)

- Twenty-first Knesset (2019)

- Twenty-second Knesset (2019–2020)

- Twenty-third Knesset (2020)

Tourism

The Knesset holds morning tours in Hebrew, Arabic, English, French, Spanish, German, and Russian on Sunday and Thursday, and there are also live session viewing times on Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday mornings.[21]

Security

The Knesset is protected by the Knesset Guard, a protective security unit responsible for the security of the Knesset building and Knesset members. Guards are stationed outside the building to provide armed protection, and ushers are stationed inside to maintain order. The Knesset Guard also plays a ceremonial role, participating in state ceremonies, which includes greeting dignitaries on Mount Herzl on the eve of Israeli Independence Day.

Public perception

A poll conducted by the Israeli Democracy Institute in April and May 2014 showed that while a majority of both Jews and Arabs in Israel are proud to be citizens of the country, both groups share a distrust of Israel's government, including the Knesset. Almost three quarters of Israelis surveyed said corruption in Israel's political leadership was either "widespread or somewhat prevalent". A majority of both Arabs and Jews trusted the Israel Defense Forces, the President of Israel, and the Supreme Court of Israel, but Jews and Arabs reported similar levels of mistrust, with little more than a third of each group claiming confidence in the Knesset.[22]

See also

Notes

References

- The Oxford Dictionary of English, Oxford University Press, 2005

- The Knesset. Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- Raoul Wootliff (5 March 2020). "Final results show Likud with 36 seats, Netanyahu bloc short of majority with 58". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- Hezki Baruch (22 December 2020). "23rd Knesset dissolved, Israel going to elections". Arutz Sheva. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- Synagogue, The Great (Heb. כְּנֶסֶת הַגְּדוֹלָה, Keneset ha-Gedolah) Jewish Virtual Library

- "Basic Laws - Introduction". Knesset. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- Legislation. Knesset.gov.il. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- Knesset Committees. Knesset.gov.il. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- The Organisation of the Work of the Knesset. Knesset.gov.il (17 February 2003). Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- "Lobbies of the Twentieth Knesset". knesset.gov.

- Ahren, Raphael (11 June 2013). "Coalition chief heading caucus that seeks to retain entire West Bank". The Times of Israel.

Knesset caucuses, sometimes called lobbies, are informal groups of parliamentarians that gather around a certain cause or topic. There are hundreds of such caucuses, but the one Levin and Strock now head is one of the largest — if not the largest, with 20-30 members in the last Knesset — and most active.

- Netanyahu considering forcing ministers to vacate Knesset seats Haaretz, 13 February 2009

- "All 120 incoming Knesset members". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- www.knesset.gov.il

- Lis, Jonathan (12 March 2014). "Israel raises electoral threshold to 3.25 percent". Haaretz. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- The Plenum - Motions of No-Confidence Knesset website

- Factional and Government Make-Up of the Second Knesset Knesset website

- Factional and Government Make-Up of the Fourth Knesset Knesset website

- Defacement in Jerusalem monastery threatens diplomatic crisis Haaretz, 8 October 2006

- Beit Froumine. Knesset.gov.il (30 August 1966). Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- Knesset Times to Visit. Knesset.gov.il. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- Pileggi, Tamar (4 January 2015). ""Tamar Pileggi 'Jews and Arabs proud to be Israeli, distrust government: Poll conducted before war shows marked rise in support for state among Arabs; religious establishment scores low on trust'". The Times of Israel.

External links

- Official website

(in English)

(in English)