Bible translations in the Middle Ages

Bible translations in the Middle Ages discussions are rare in contrast to Late Antiquity, when the Bibles available to most Christians were in the local vernacular. In a process seen in many other religions, as languages changed, and in Western Europe languages with no tradition of being written down became dominant, the prevailing vernacular translations remained in place, despite gradually becoming sacred languages, incomprehensible to the majority of the population in many places. In Western Europe, the Latin Vulgate, itself originally a translation into the vernacular, was the standard text of the Bible, and full or partial translations into a vernacular language were uncommon until the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period.

Classical and Late Antique translations

Greek texts and versions

The books of the Bible were not originally written in Latin. The Old Testament was written in Hebrew (with some parts in Greek and Aramaic[2]) and the New Testament in Greek. The Septuagint, still used in the Greek Orthodox church, is a Jewish translation of the Old Testament into Koine Greek completed in the 1st century BC in Alexandria for Jews who spoke Greek as their primary language.

The whole Christian Bible was therefore available in Koine Greek by about 100 AD; so were numerous apocryphal Gospels. Deciding which books should be included in the Biblical canon took about another two centuries; some differences remain between churches to the present day. The Septuagint also included some books that are not in the Hebrew Bible, which the church accepted due to their use at the time of Christ and because Christ quoted directly from and/or referenced these books in the Gospels of the New Testament.

Other early versions

The Bible was translated into various languages in late antiquity; the most important of these translations are those in the Syriac dialect of Aramaic (including the Peshitta and the Diatessaron gospel harmony), the Ge'ez language of Ethiopia, and, in Western Europe, Latin. The earliest Latin translations are collectively known as the Vetus Latina, but in the late fourth century, Jerome re-translated the Hebrew and Greek texts into the normal vernacular Latin of his day, in a version known as the Vulgate (Biblia vulgata) (meaning "common version", in the sense of "popular"). Jerome's translation gradually replaced most of the older Latin texts, and also gradually ceased to be a vernacular version as the Latin language developed and divided. The earliest surviving complete manuscript of the entire Latin Bible is the Codex Amiatinus, produced in eighth century England at the double monastery of Wearmouth-Jarrow. By the end of late antiquity the Bible was therefore available and used in all the major written languages then spoken by Christians.

Vetus Latina, or the Old Latin

Usage of the Vetus Latina as the backbone of the church and liturgy continued well into the Twelfth Century. Perhaps the most complete, and certainly the largest surviving example is Codex Gigas, which can be seen in its entirety online.[3] Housed in the National Library of Sweden, the massive Bible opens with the Five Books of Moses and ends with Third Book of Kings.

Latin Vulgate, or Jerome's Revision of the Vetus Latina

When Jerome's revision, or update of the Vetus Latina, was read aloud in the churches in North Africa, riots and protests erupted since the new readings differed - the turn of the phrase - from the more familiar reading in the Vetus Latina. Jerome's Latin Vulgate did not take complete traction among the churches in the West until the time of Charlemagne, when he sought to standardize script, texts, and rites within Western Christendom.

Early medieval vernacular translations

During the Migration Period Christianity spread to various peoples who had not been part of the old Roman Empire, and whose languages had as yet no written form, or only a very simple one, like runes. Typically the Church itself was the first to attempt to capture these languages in written form, and Bible translations are often the oldest surviving texts in these newly written-down languages. Meanwhile, Latin was evolving into new distinct regional forms, the early versions of the Romance languages, for which new translations eventually became necessary. However, the Vulgate remained the authoritative text, used universally in the West for scholarship and the liturgy since the early development of the Romance languages had not come to full fruition, matching its continued use for other purposes such as religious literature and most secular books and documents. In the early Middle Ages, anyone who could read at all could often read Latin, even in Anglo-Saxon England, where writing in the vernacular (Old English) was more common than elsewhere. A number of pre-reformation Old English Bible translations survive, as do many instances of glosses in the vernacular, especially in the Gospels and the Psalms.[4] Over time, biblical translations and adaptations were produced both within and outside the church, some as personal copies for religious or lay nobility, others for liturgical or pedagogical purposes.[5][6]

Innocent III, "heretical" movements and "translation controversies"

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Church attitudes toward written translations and the use of the vernacular in Mass varied by the translation, the date and location. For example, whereas the acts of Saint-Gall contain a reference to the use of a vernacular interpreter in Mass as early as the seventh century, and the 813 Council of Tours acknowledge the need for translation and encouraged such,[7] in 1079, Duke Vratislaus II of Bohemia asked Pope Gregory VII for permission to use Old Church Slavonic translations of the liturgy, to which Gregory did not consent.[8]

In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, demand for vernacular translations came from groups outside the Roman Catholic Church such as the Waldensians, Paterines and Cathars. This was probably related to the increased urbanization of the twelfth-century, as well as increased literacy among educated urban populations.[9][10]

A well-known group of letters from Pope Innocent III to the diocese of Metz, where the Waldensians were active, is sometimes taken by post-reformation scholars as evidence that Bible translations were forbidden by the church, especially since Innocent's first letter was later incorporated into canon law.[11]

Margaret Deanesly's study of this matter in 1920 was influential in maintaining this notion for many years, but later scholars have challenged its conclusions. Leonard Boyle has argued that, on the contrary, Innocent was not particularly concerned with the translations, but rather with their use by unauthorized and uneducated preachers.[12] "There is not in fact the slightest hint that Innocent ever spoke in any way, hypothetically or not, of suppressing the translations at all."[13] The thirteenth-century chronicler Alberic of Trois Fontaines does say that translations were burned in Metz in 1200, and Deanesly understood this to mean it was ordered by Innocent in his letters from the previous year, but Boyle pointed out that nowhere in the letters did Innocent actually prohibit the translations.[14] While the documents are inconclusive about the fate of the specific translations in question and their users, Innocent’s general remarks suggest a rather permissive attitude toward translations and vernacular commentaries provided that they are produced and used within the scope of Christian teachings or with church oversight.

There is no evidence of any official decision to universally disallow translations following the incident at Metz until the Council of Trent, at which time the Reformation threatened the Catholic Church, and the rediscovery of the Greek New Testament presented new problems for translators. However, some specific translations were condemned, and regional bans were imposed during the Albigensian Crusade: Toulouse in 1229, Taragona in 1234 and Beziers in 1246.[15][16] Pope Gregory IX incorporated Innocent III’s letter into his Decretals and instituted these bans presumably with the Cathars in mind as well as the Waldensians, who continued to preach using their own translations, spreading into Spain and Italy, as well as the Holy Roman Empire. Production of Wycliffite Bibles would later be officially banned in England at the Oxford Synod in the face of Lollard anticlerical sentiment, but the ban was not strictly enforced and since owning earlier copies was not illegal, books made after the ban are often simply inscribed with a date prior to 1409 to avoid seizure.

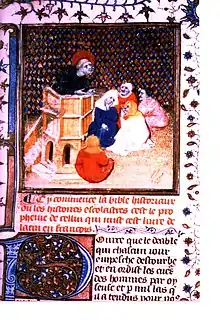

As Rosemarie Potz McGerr has argued, as a general pattern, bans on translation responded to the threat of strong heretical movements; in the absence of viable heresies, a variety of translations and vernacular adaptations flourished between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries with no documented institutional opposition at all.[17] Still, translations came late in the history of the European vernaculars and were relatively rare in many areas. According to the Cambridge History of the Bible, this was mainly because "the vernacular appeared simply and totally inadequate. Its use, it would seem, could end only in a complete enfeeblement of meaning and a general abasement of values. Not until a vernacular is seen to possess relevance and resources, and, above all, has acquired a significant cultural prestige, can we look for acceptable and successful translation."[18] The cost of commissioning translations and producing such a large work in manuscript was also a factor; the three copies of the Vulgate produced in 7th century Northumbria, of which the Codex Amiatinus is the only survivor, are estimated to have required the skins of 1,600 calves.[19] Manuscript copies of the Bible historiale and, even more so, the usually lushly illuminated Bible moralisée were large, deluxe manuscripts, which only the wealthiest nobility (such as the French royal family) could afford.

Notable medieval vernacular Bibles by language, region and type

English

There are a number of partial Old English Bible translations (from the Latin) surviving, including the Old English Hexateuch, Wessex Gospels and the Book of Psalms, partly in prose and partly in a different verse version. Others, now missing, are referred to in other texts, notably a lost translation of the Gospel of John into Old English by the Venerable Bede, which he is said to have completed shortly before his death around the year 735. Alfred the Great had a number of passages of the Bible circulated in the vernacular about 900, and in about 970 an inter-linear translation was added in red to the Lindisfarne Gospels.[20] These included passages from the Ten Commandments and the Pentateuch, which he prefixed to a code of laws he promulgated around this time. In approximately 990, a full and freestanding version of the four Gospels in idiomatic Old English appeared, in the West Saxon dialect; these are called the Wessex Gospels. According to the historian Victoria Thompson, "although the Church reserved Latin for the most sacred liturgical moments almost every other religious text was available in English by the eleventh century".[21]

After the Norman Conquest, the Ormulum, produced by the Augustinian monk Orm of Lincolnshire around 1150, includes partial translations of the Gospels and Acts of the Apostles from Latin into the dialect of East Midland. The manuscript is written in the poetic meter iambic septenarius.

Richard Rolle of Hampole (or de Hampole) was an Oxford-educated hermit and writer of religious texts. In the early 14th century, he produced English glosses of Latin Bible text, including the Psalms. Rolle translated the Psalms into a Northern English dialect, but later copies were written in Southern English dialects. Around the same time, an anonymous author in the West Midlands region produced another gloss of the Psalms — the West Midland Psalms.

In the early years of the 14th century, a French copy of the Book of Revelation was anonymously translated into English, and there were English versions of various French paraphrases and moralized versions.

In the late 14th century, John Wycliffe and perhaps Nicholas Hereford produced the first complete English language Bible. Wycliffe's Bible was revised in the last years of the 14th century, resulting in two major editions, the second more numerous than the first, both circulating widely despite their official prohibition at the Oxford Synod.

Western Continental Europe

The first French translation dates from the thirteenth century, as does the first Catalan Bible, and the Spanish Biblia Alfonsina. The most notable Middle English Bible translation, Wycliffe's Bible (1383), based on the Vulgate, was banned by the Oxford Synod of 1407-08, and was associated with the movement of the Lollards, often accused of heresy. The Malermi Bible was an Italian translation printed in 1471. In 1478, there was a Catalan translation in the dialect of Valencia. The Welsh Bible and the Alba Bible, a Jewish translation into Castilian, date from the 15th century.

French

Translations of individual books of the Bible and verse adaptations survive from the twelfth century, but the first prose Bible collections date from the mid thirteenth. These include the Acre Bible, an Old Testament produced in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, likely for King Louis IX of France,[22] the Anglo-Norman Bible and a glossed, complete translation of the Paris Bible known simply as the “Thirteenth-Century Bible” or “Old French Bible,” often referred to by the French title “Bible du XIIIe siècle” first coined by Samuel Berger.[23][24][25]

Completed with prologues in 1297 by Guyart des Moulins, the Bible historiale was by far the predominant medieval translation of the Bible into French throughout the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. It translates from the Latin Vulgate significant portions from the Bible accompanied by selections from the Historia Scholastica by Peter Comestor (d. ca. 1178), a literal-historical commentary that summarizes and interprets episodes from the historical books of the Bible and situates them chronologically with respect to events from pagan history and mythology. In many copies, Guyart’s translation has been supplemented with some individual biblical books from the ‘’Bible du XIIIe siècle’’.[26]

(Castilian) Spanish

The Biblia alfonsina, or Alfonsine Bible, is a 1280 translation of the Bible into Castilian Spanish. It represents the earliest Spanish translation of the Vulgate as well as the first translation into a European language. The work was commissioned by Alfonso X and carried out under the Toledo School of Translators. Only small fragments of the work survive today.[27] The Biblia de Alba or Alba Bible, is a translation of the Old Testament into Castilian Spanish from Hebrew, Aramaic, and Latin. It was commissioned by John II of Castile and Luis González de Guzmán, Master of the Order of Calatrava. The Alba Bible was completed between 1422 and 1433.[28]

German

An Old High German version of the gospel of Matthew dates to 748. In the late Middle Ages, Deanesly thought that Bible translations were easier to produce in Germany, where the decentralized nature of the Empire allowed for greater religious freedom. However, these translations were seized and burned by inquisitors whenever they were found.[29] Altogether there are 13 medieval German translations before the Luther Bible.[30] In 1466, Johannes Mentelin published the first printed Bible in the German language, the Mentelin Bible, one of the first printed books in the German language and also the first printed vernacular Bible. The Mentelin Bible was reprinted in the southern German region a further thirteen times by various printers up until the Luther Bible. About 1475 Günther Zainer of Augsburg printed an illustrated German edition of the Bible, with a second edition in 1477.

Czech

All medieval translations of the Bible into Czech were based on the Latin Vulgate. The Psalms were translated into Czech before 1300 and the gospels followed in the first half of the 14th century. The first translation of the whole Bible into Czech was done around 1360. Until the end of the 15th century this translation was revisioned and edited three times. After 1476 the first printed Czech New Testament was published in Pilsen. In 1488 the Prague Bible was published as the oldest Czech printed Bible, thus the Czech language became the fifth language in which the entire Bible was printed (after Latin, German, Italian and Catalan).

Eastern Europe

Some fragments of the Bible were probably translated into Lithuanian when that country was converted to Christianity in the 14th century. A Hungarian Hussite Bible appeared in the mid 15th century, of which only fragments remain.

Other Germanic and Slavonic languages

The earliest translation into a vernacular European language other than Latin or Greek was the Gothic Bible, by Ulfilas, an Arian who translated from the Greek in the 4th century in Italy.

The translation into Old Church Slavonic by Cyril and Methodius dates to the late 9th century though whether Cyril had to invent the Glagolitic alphabet for the purpose remains controversial. Versions of Church Slavonic language remain the liturgical languages of the Slavic Eastern Orthodox churches, though subject to some modernization.

Arabic

In the 10th century, Saadia Gaon translated the Old Testament in Arabic. Ishaq ibn Balask of Cordoba translated the gospels into Arabic in 946.[31] Hafs ibn Albar made a translation of the Psalms in 889.[32]

Poetic and pictorial works

Throughout the Middle Ages, Bible stories were always known in the vernacular through prose and poetic adaptations, usually greatly shortened and freely reworked, especially to include typological comparisons between Old and New Testaments. Some parts of the Bible stories were paraphrased in verse by Anglo-Saxon poets, e.g. Genesis and Exodus, and in French by Hermann de Valenciennes, Macé de la Charité, Jehan Malkaraume and others. Among the most popular compilations were the many varying versions of the Bible moralisée, Biblia pauperum and Speculum Humanae Salvationis. These were increasingly in the vernacular, and often illustrated. 15th century blockbook versions could be relatively cheap, and appear in the prosperous Netherlands to have included among their target market parish priests who would use them for instruction.[33]

Historical works

Historians also used the Bible as a source and some of their works were later translated into a vernacular language: for example Peter Comestor's popular commentaries were incorporated into Guyart des Moulins French translation, the Bible historiale and the Middle English Genesis and Exodus, and were an important source for a vast array of biblically-themed poems and histories in a variety of languages. It was the convention of many if not most historical chronicles to begin at Creation and include a few biblical events as well as secular ones from Roman and local history before reaching their real subject; the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle follows this convention.

Notes

- Walther & Wolf, pp. 242-47

- Parts of the Book of Daniel and Book of Ezra

- https://www.wdl.org/en/item/3042/

- For instance, see Roberts, Jane (2011). “Some Psalter Glosses in Their Immediate Context”, in Palimpsests and the Literary Imagination of Medieval England, eds. Leo Carruthers, Raeleen Chai-Elsholz, Tatjana Silec. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 61-79, which looks at three Anglo-Saxon glossed psalters and how layers of gloss and text, language and layout, speak to the meditative reader, or Marsden, Richard (2011), "The Bible in English in the Middle Ages", in The Practice of the Bible in the Middle Ages: Production, Reception and Performance in Western Christianity (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011), pp. 272-295.

- Deanesly, Margaret (1920) The Lollard Bible and Other Medieval Biblical Versions. Cambridge University Press, p. 19

- Lampe (1975)

- Gustave Masson (1866), pp. 81-83.

- Deanesly (1920), p. 24

- Kienzle, Beverly Mayne (1998) "Holiness and obedience"; pp. 259-60.

- Biller (1994)

- Deanesly (1920), p. 34.

- Boyle, Leonard E. (1985) "Innocent III and vernacular versions of Scripture"; p. 101.

- Boyle, pg. 105

- Boyle (1985), p. 105.

- McGerr (1983), p. 215

- Anderson, Trevor. "Vernacular Scripture in the Reformation Era: Re-examining the Narrative". The Regensburg Forum. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- McGerr (1983)

- Lampe, G. W. H. (ed.) (1975) The Cambridge History of the Bible, vol. 2: The West from the Fathers to the Reformation, p. 366.

- Chris Grocock has some calculations in Mayo of the Saxons and Anglican Jarrow, Evidence for a Monastic Economy Archived 2012-02-26 at the Wayback Machine, according to which sheep required only one third as much land per page as calves. 1,600 calves seems to be the standard estimate, see John, Eric (1996), Reassessing Anglo-Saxon England, Manchester: Manchester University Press, p. 14, ISBN 0-7190-5053-7

- Lindisfarne Gospels British Library

- Thompson (2004), p. 4

- Nobel (2002)

- Berger (1884)

- Sneddon (2002)

- C. A. Robson, “Vernacular Scriputres in France” in Lampe, ‘’Cambridge History of the Bible’’ (1975)

- Berger (1884), pp. 109-220

- Serrano, Rafael (29 de enero de 2014). «La Biblia alfonsina». Historia de la Biblia en español. Accessed 22 June 2020.

- John Fletcher y Alfonso Ropero, Historia de las versiones castellanas de la Biblia, en Historia General del Cristianismo: Del Siglo I al Siglo XXI, Clie, 2008, ISBN 8482675192, pg. 479.

- Deanesly (1920), pp. 54-61.

- Walther & Wolf, p. 242

- Ann Christys, Christians in Al-Andalus, 2002, p. 155

- Ann Christys, Christians in Al-Andalus, 2002, p. 155

- Wilson & Wilson, especially pp. 26-30, 120

Sources

- Berger, Samuel. (1884) ‘’La Bible française au moyen âge: étude sur les plus anciennes versions de la Bible écrites en prose de langue d'oï’’l. Paris: Imprimerie nationale.

- Biller, Peter and Anne, eds. (1994). Hudson. Heresy and Literacy, 1000-1530. Cambridge Studies in Medieval Literature. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Boyle, Leonard E. (1985) "Innocent III and Vernacular Versions of Scripture", in The Bible in the Medieval World: essays in memory of Beryl Smalley, ed. Katherine Walsh and Diana Wood, (Studies in Church History; Subsidia; 4.) Oxford: Published for the Ecclesiastical History Society by Blackwell

- Deanesly, Margaret (1920) The Lollard Bible and Other Medieval Biblical Versions. Cambridge: University Press

- Kienzle, Beverly Mayne (1998) "Holiness and Obedience: denouncement of twelfth-century Waldensian lay preaching", in The Devil, Heresy, and Witchcraft in the Middle Ages: Essays in Honor of Jeffrey B. Russell, ed. Alberto Ferreiro. Leiden: Brill

- Lampe, G. W. H. (1975) The Cambridge History of the Bible, vol. 2: The West from the Fathers to the Reformation. Cambridge: University Press

- Masson, Gustave (1866). “Biblical Literature in France during the Middle Ages: Peter Comestor and Guiart Desmoulins.” ‘’The Journal of Sacred Literature and Biblical Record’’ 8: 81-106.

- McGerr, Rosemarie Potz (1983). “Guyart Desmoulins, the Vernacular Master of Histories, and His ‘’Bible Historiale’’.” ‘’Viator’’ 14: 211-244.

- Nobel, Pierre (2001). “Early Biblical Translators and their Readers: the Example of the ‘’Bible d'Acre and the Bible Anglo-Normande’’.” ‘’Revue de linguistique romane ‘’66, no. 263-4 (2002): 451-472.

- Salvador, Xavier-Laurent (2007). ‘’Vérité et Écriture(s).’’ Bibliothèque de grammaire et de linguistique 25. Paris: H. Champion.

- Sneddon, Clive R. (2002). “The 'Bible Du XIIIe Siècle': Its Medieval Public in Light of its Manuscript Tradition.” ‘’Nottingham Medieval Studies’’ 46: 25-44.

- Thompson, Victoria (2004). Dying and Death in Later Anglo-Saxon England. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-070-1.

- Walther, Ingo F. and Wolf, Norbert (2005) Masterpieces of Illumination (Codices Illustres), Köln: Taschen ISBN 3-8228-4750-X

- Wilson, Adrian, and Wilson, Joyce Lancaster (1984) A Medieval Mirror: "Speculum humanae salvationis", 1324-1500 . Berkeley: University of California Press online edition Includes a full set of woodcut pictures with notes from the Speculum Humanae Salvationis in Chapter 6.