Old Spanish

Old Spanish, also known as Old Castilian (Spanish: castellano antiguo; Old Spanish: romance castellano [roˈmantse kasteˈʎano]) or Medieval Spanish (Spanish: español medieval), was originally a dialect of Vulgar Latin spoken in the former provinces of the Roman Empire that provided the root for the early form of the Spanish language that was spoken on the Iberian Peninsula from the 10th century until roughly the beginning of the 15th century, before a consonantal readjustment gave rise to the evolution of modern Spanish. The poem Cantar de Mio Cid (The Poem of the Cid), published around 1200, remains the best known and most extensive work of literature in Old Spanish.

| Old Spanish | |

|---|---|

| Old Castilian | |

| romance castellano | |

| Pronunciation | [roˈmantse kasteˈʎano] |

| Native to | Crown of Castile |

| Region | Iberian peninsula |

| Ethnicity | Castilians, later Spaniards |

| Era | 10th–15th centuries |

| Latin | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | osp |

osp | |

| Glottolog | olds1249 |

Phonology

| Spanish language |

|---|

|

| Overview |

| History |

| Grammar |

| Dialects |

| Dialectology |

| Interlanguages |

| Teaching |

The phonological system of Old Spanish was quite similar to that of other medieval Romance languages.

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | labialised | |||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | (ŋ) | ||

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | k | kʷ | |

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | ɡʷ | ||

| Affricate | voiceless | t͡s | t͡ʃ | |||

| voiced | d͡z | d͡ʒ ~ ʒ | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | ||

| voiced | v | z | ʒ ~ d͡ʒ | |||

| Approximant | central | j | w | |||

| lateral | l | ʎ, jl | ||||

| Rhotic | r | |||||

| Flap | ɾ | |||||

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Close-mid | e | o | |

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɔ | |

| Open | a |

Sibilants

Among the consonants, there were seven sibilants, including three sets of voiceless/voiced pairs:

- Voiceless alveolar affricate /t͡s̻/: represented by ⟨ç⟩ before ⟨a⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨u⟩, and by ⟨c⟩ before ⟨e⟩ or ⟨i⟩

- Voiced alveolar affricate /d͡z̻/: represented by ⟨z⟩

- Voiceless apicoalveolar fricative /s̺/: represented by ⟨s⟩ in word-initial and word-final positions and before and after a consonant, and by ⟨ss⟩ between vowels

- Voiced apicoalveolar fricative /z̺/: represented by ⟨s⟩ between vowels and before voiced consonants

- Voiceless postalveolar fricative /ʃ/: represented by ⟨x⟩ (pronounced like the English digraph ⟨sh⟩)

- Voiced postalveolar fricative /ʒ/: represented by ⟨j⟩, and (often) by ⟨g⟩ before ⟨e⟩ or ⟨i⟩ (pronounced like the si in English vision)

- Voiceless postalveolar affricate /t͡ʃ/: represented by ⟨ch⟩

The set of sounds is identical to that found in medieval Portuguese and almost the same as the system present in the modern Mirandese language.

The Modern Spanish system evolved from the Old Spanish one with the following changes:

- The affricates /t͡s̻/ and /d͡z̻/ were simplified to laminodental fricatives /s̻/ and /z̻/, which remained distinct from the apicoalveolar sounds /s̺/ and /z̺/ (a distinction also present in Basque).

- The voiced sibilants then all lost their voicing and so merged with the voiceless ones. (Voicing remains before voiced consonants, such as mismo, desde, and rasgo, but only allophonically.)

- The merged /ʃ/ was retracted to /x/.

- The merged /s̻/ was drawn forward to /θ/. In some parts of Andalusia and the Canary Islands, however (and so then in Latin America), the merged /s̺/ was instead drawn forward, merging into /s̻/.

Changes 2–4 all occurred in a short period of time, around 1550–1600. The change from /ʃ/ to /x/ is comparable to the same shift occurring in Modern Swedish (see sj-sound).

The Old Spanish spelling of the sibilants was identical to modern Portuguese spelling, which, unlike Spanish, still preserves most of the sounds of the medieval language, and so is still a mostly faithful representation of the spoken language. Spanish spelling was altered in 1815 to reflect the changed pronunciation:[1]

- passar "to pass" vs. casar "to marry" (Modern Spanish pasar, casar, cf. Portuguese passar, casar)

- osso "bear" vs. oso "I dare" (Modern Spanish oso in both cases, cf. Portuguese urso [a borrowing from Latin], ouso)

- foces "sickles" vs. fozes "base levels" (Modern Spanish hoces in both cases, cf. Portuguese foices, fozes)

- coxo "lame" vs. cojo "I seize" (Modern Spanish cojo in both cases, cf. Portuguese coxo, colho)

- xefe "chief" (Modern Spanish jefe, cf. Portuguese chefe)

- Xeres (Modern Spanish Jerez, cf. Portuguese Xerez)

- oxalá "if only" (Modern Spanish ojalá, cf. Portuguese oxalá)

- dexar "leave" (Modern Spanish dejar, cf. Portuguese deixar)

- roxo "red" (Modern Spanish rojo, cf., Portuguese roxo "purple")

- fazer or facer "make" (Modern Spanish hacer, cf. Portuguese fazer)

- dezir "say" (Modern Spanish decir, cf. Portuguese dizer)

- lança "lance" (Modern Spanish lanza, cf. Portuguese lança)

The Old Spanish origins of jeque and jerife reflect their Arabic origins, xeque from Arabic sheikh and xerife from Arabic sharif.

b and v

The letters ⟨b⟩ and ⟨v⟩ still had distinct pronunciations; ⟨b⟩ still represented a stop consonant [b] in all positions, and ⟨v⟩ was likely pronounced as a voiced bilabial fricative or approximant [β] or [β̞] (although word-initially, it may have been pronounced [b]). The use of ⟨b⟩ and ⟨v⟩ in Old Spanish largely corresponded to their use in Modern Portuguese, which distinguishes the two sounds except in northern European dialects. The phonological distinction of the two sounds also occurs in several dialects of Catalan (central and southern Valencian, an area in southern Catalonia, the Balearic dialect and Alguerese), though not in Standard Catalan from eastern Catalonia. When Spanish spelling was reformed in 1815, words with ⟨b⟩ and ⟨v⟩ were respelled etymologically to match the Latin spelling whenever possible:

- aver (Modern Spanish haber, compare Latin habēre, Portuguese haver)

- caber (Modern Spanish caber, compare Latin capere, Portuguese caber)

- bever (Modern Spanish beber, compare Latin bibere; Portuguese beber < older bever)

- bivir or vivir (Modern Spanish vivir, compare Latin vīvere, Portuguese viver)

- amava (Modern Spanish amaba, compare Latin amābam/amābat, Portuguese amava)

- saber (Modern Spanish saber, compare Latin sapere, Portuguese saber)

- livro (Modern Spanish libro, compare Latin līber, Portuguese livro)

- palavra (Modern Spanish palabra, compare Latin parabola, Portuguese palavra)

f and h

Many words now written with an ⟨h⟩ were written with ⟨f⟩ in Old Spanish, but it was likely pronounced [h] in most positions (but [ɸ] or [f] before /r/, /l/, [w] and possibly [j]). The cognates of the words in Portuguese and most other Romance languages have [f]. Other words now spelled with an etymological ⟨h⟩ were spelled without any such consonant in Old Spanish: haber, written aver in Old Spanish). Such words have cognates in other Romance languages without [f] (e.g. French avoir, Italian avere, Portuguese haver with silent etymological ⟨h⟩):

- fablar (Modern Spanish hablar, Portuguese falar)

- fazer or facer (Modern Spanish hacer, Portuguese fazer)

- fijo (Modern Spanish hijo, Portuguese filho)

- foces "sickles", fozes "base levels" (Modern Spanish hoces, Portuguese foices, fozes)

- follín (Modern Spanish hollín)

- ferir (Modern Spanish herir, Portuguese ferir)

- fiel (Modern Spanish fiel, Portuguese fiel)

- fuerte (Modern Spanish fuerte, Portuguese forte)

- flor (Modern Spanish flor, Portuguese flor)

Modern words with ⟨f⟩ before a vowel mostly represent learned or semi-learned borrowings from Latin: fumar "to smoke" (compare inherited humo "smoke"), satisfacer "to satisfy" (compare hacer "to make"), fábula "fable, rumor" (compare hablar "to speak"). Certain modern words with ⟨f⟩ that have doublets in ⟨h⟩ may represent dialectal developments or early borrowings from nearby languages: fierro "branding iron" (compare hierro "iron"), fondo "bottom" (compare hondo "deep"), Fernando "Ferdinand" (compare Hernando).

ch

Old Spanish had ⟨ch⟩, just as Modern Spanish does, which mostly represents a development of earlier */jt/ (still preserved in Portuguese and French), from the Latin ct. The use of ⟨ch⟩ for /t͡ʃ/ originated in Old French and spread to Spanish, Portuguese, and English despite the different origins of the sound in each language:

- leche "milk" from earlier leite (Latin lactem, cf. Portuguese leite, French lait)

- mucho "much", from earlier muito (Latin multum, cf. Portuguese muito, French moult (rare, regional))

- noche "night", from earlier noite (Latin noctem, cf. Portuguese noite, French nuit)

- ocho "eight", from earlier oito (Latin octō, cf. Portuguese oito, French huit)

- hecho "made" or "fact", from earlier feito (Latin factum, cf. Portuguese feito, French fait)

Palatal nasal

The palatal nasal /ɲ/ was written ⟨nn⟩ (the geminate nn being one of the sound's Latin origins), but it was often abbreviated to ⟨ñ⟩ following the common scribal shorthand of replacing an ⟨m⟩ or ⟨n⟩ with a tilde above the previous letter. Later, ⟨ñ⟩ was used exclusively, and it came to be considered a letter in its own right by Modern Spanish. Also, as in modern times, the palatal lateral /ʎ/ was indicated with ⟨ll⟩, again reflecting its origin from a Latin geminate.

Spelling

Greek digraphs

The Graeco-Latin digraphs (digraphs in words of Greek-Latin origin) ⟨ch⟩, ⟨ph⟩, ⟨(r)rh⟩ and ⟨th⟩ were reduced to ⟨c⟩, ⟨f⟩, ⟨(r)r⟩ and ⟨t⟩, respectively:

- christiano (Modern Spanish cristiano)

- triumpho (Modern Spanish triunfo)

- myrrha (Modern Spanish mirra)

- theatro (Modern Spanish teatro)

Word-initial Y to I

Word-initial [i] was spelled Y, which was simplified to letter I.

Morphology

In Old Spanish, perfect constructions of movement verbs, such as ir ('(to) go') and venir ('(to) come'), were formed using the auxiliary verb ser ('(to) be'), as in Italian and French: Las mugieres son llegadas a Castiella was used instead of Las mujeres han llegado a Castilla ('The women have arrived in Castilla').

Possession was expressed with the verb aver (Modern Spanish haber, '(to) have'), rather than tener: Pedro ha dos fijas was used instead of Pedro tiene dos hijas ('Pedro has two daughters').

In the perfect tenses, the past participle often agreed with the gender and number of the direct object: María ha cantadas dos canciones was used instead of Modern Spanish María ha cantado dos canciones ('María has sung two songs'). However, that was inconsistent even in the earliest texts.

Personal pronouns and substantives were placed after the verb in any tense or mood unless a stressed word was before the verb.

The future and the conditional tenses were not yet fully grammaticalised as inflections; rather, they were still periphrastic formations of the verb aver in the present or imperfect indicative followed by the infinitive of a main verb. [2] Pronouns, therefore, by the general placement rules, could be inserted between the main verb and the auxiliary in these periphrastic tenses, as still occurs with Portuguese (mesoclisis):

- E dixo: ― Tornar-m-é a Jherusalem. (Fazienda de Ultra Mar, 194)

- Y dijo: ― Me tornaré a Jerusalén. (literal translation into Modern Spanish)

- E disse: ― Tornar-me-ei a Jerusalém. (literal translation into Portuguese)

- And he said: "I will return to Jerusalem." (English translation)

- En pennar gelo he por lo que fuere guisado (Cantar de mio Cid, 92)

- Se lo empeñaré por lo que sea razonable (Modern Spanish equivalent)

- Penhorá-lo-ei pelo que for razoável (Portuguese equivalent)

- I will pawn them it for whatever it be reasonable (English translation)

When there was a stressed word before the verb, the pronouns would go before the verb: non gelo empeñar he por lo que fuere guisado.

Generally, an unstressed pronoun and a verb in simple sentences combined into one word. In a compound sentence, the pronoun was found in the beginning of the clause: la manol va besar = la mano le va a besar.

The future subjunctive was in common use (fuere in the second example above) but it is generally now found only in legal or solemn discourse and in the spoken language in some dialects, particularly in areas of Venezuela, to replace the imperfect subjunctive.[3] It was used similarly to its Modern Portuguese counterpart, in place of the modern present subjunctive in a subordinate clause after si, cuando etc., when an event in the future is referenced:

- Si vos assi lo fizieredes e la ventura me fuere complida

- Mando al vuestro altar buenas donas e Ricas (Cantar de mio Cid, 223–224)

- Si vosotros así lo hiciereis y la ventura me fuere cumplida,

- Mando a vuestro altar ofrendas buenas y ricas (Modern Spanish equivalent)

- Se vós assim o fizerdes e a ventura me for comprida,

- Mando a vosso altar oferendas boas e ricas. (Portuguese equivalent; 'ventura' is an obsolete word for 'luck'.)

- If you do so and fortune is favourable toward me,

- I will send to your altar fine and rich offerings (English translation)

Vocabulary

| Latin | Old Spanish | Modern Spanish | Modern Portuguese |

|---|---|---|---|

| acceptare, captare, effectum, respectum | acetar, catar, efeto, respeto | aceptar, captar, efecto, respecto and respeto | aceitar, captar, efeito, respeito |

| et, non, nos, hic | e, et; non, no; nós; í | y, e; no; nosotros; ahí | e; não; nós; aí |

| stabat; habui, habebat; facere, fecisti | estava; ove, avié; far/fer/fazer, fezist(e)/fizist(e) | estaba; hube, había; hacer, hiciste | estava; houve, havia; fazer, fizeste |

| hominem, mulier, infantem | omne/omre/ombre, mugier/muger, ifante | hombre, mujer, infante | homem, mulher, infante |

| cras, mane (maneana); numquam | cras, man, mañana; nunqua/nunquas | mañana, nunca | manhã, nunca |

| quando, quid, qui (quem), quo modo | quando, que, qui, commo/cuemo | cuando, que, quien, como | quando, que, quem, como |

| fīlia | fyia, fija | hija | filha |

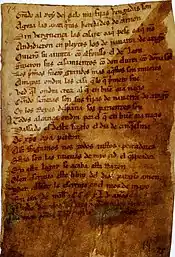

Sample text

The following is a sample from Cantar de Mio Cid (lines 330–365), with abbreviations resolved, punctuation (the original has none), and some modernized letters.[4] Below is the original Old Spanish text in the first column, along with the same text in Modern Spanish in the second column and an English translation in the third column.

An extract with the presumed pronunciation of old Spanish can be heard in this audio.

|

|

|

See also

- History of the Spanish language

- Early Modern Spanish (Middle Spanish)

References

- Ortografía de la lengua castellana – Real Academia Española –. Imprenta real. 1815. Retrieved 2015-05-22 – via Internet Archive.

ortografía 1815.

- A History of the Spanish Language. Ralph Penny. Cambridge University Press. Pag. 210.

- Diccionario de dudas y dificultades de la lengua española. Seco, Manuel. Espasa-Calpe. 2002. Pp. 222–3.

- A recording with reconstructed mediaeval pronunciation can be accessed here, reconstructed according to contemporary phonetics (by Jabier Elorrieta).