Bitola inscription

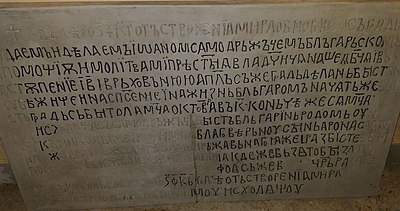

The Bitola inscription is a medieval Bulgarian stone inscription written in the Old Church Slavonic language in the Cyrillic alphabet.[1] Currently, it is located at the Institute and Museum of Bitola, North Macedonia among the permanent exhibitions as a significant epigraphic monument, described as "a marble slab with Cyrillic letters of Ivan Vladislav from 1015/17".[2]

History

Finding

The inscription was found in Bitola in 1956 during the demolition of the Sungur Chaush-Bey mosque. The mosque was the first mosque that was built in Bitola, in 1435. It is located on the left bank of the River Dragor near the old Sheep Bazaar.[3] The stone inscription was found under the doorstep of the main entrance and it is possible that it was taken as a building material from the ruins of the medieval fortress. The medieval fortress was destroyed by the Ottomans during the conquest of the town in 1385. According to the inscription, the fortress of Bitola was reconstructed on older foundations in the period between the autumn of 1015 and the spring of 1016. At that time Bitola was a capital and central military base for the First Bulgarian Empire. After the death of John Vladislav in the Battle of Dyrrhachium in 1018, the local boyars surrendered the town to the Byzantine emperor Basil II. This act saved the fortress from destruction. The old fortress was located most likely on the place of the today Ottoman Bedesten of Bitola.[4]

Decryption

After the inscription was found, information about the plate was immediately announced in the city. It was brought to Bulgaria with the help of the local activist Pande Eftimov. A fellow told him that he had found a stone inscription while working on a new building and that the word "Bulgarians" was on it.[5] The following morning, they went to the building where Eftimov took a number of photographs which were later given to the Bulgarian embassy in Belgrade.[6] His photos were sent to diplomatic channels in Bulgaria and were classified. In 1959, the Bulgarian journalist Georgi Kaloyanov sent his own photos of the inscription to the Bulgarian scientist Aleksandar Burmov, who published them in Plamak magazine. Meanwhile, the plate was transported to the local museum repository. At that time, Bulgaria avoided publicising this information as Belgrade and Moscow had significantly improved their relations after the Tito-Stalin split in 1948. However, after 1963, the official authorities openly began criticizing the Bulgarian position on the Macedonian Question, and thus changed its position.

In 1966, a new report on the inscription by Vladimir Moshin, a Russian emigrant living in Yugoslavia, was published.[7] As a result Bulgarian scientists Yordan Zaimov and his wife, Vasilka Tapkova-Zaimova, travelled to Bitola in 1968.[6] At the Bitola Museum, they made a secret rubbing from the inscription.[8] Zaimova claims that no one stopped them from working on the plate in Bitola.[6] As such, they deciphered the text according to their own interpretation of it, which was published by the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences in 1970.[9] Finally, the Macedonian researcher Ugrinova-Skalovska published her translation of the inscription in 1975.

Text

Part of the text is missing, as the inscription was used as a step of the Sungur Chaush-Bey mosque and therefore the first row was destroyed. The reconstruction of the Macedonian scientist prof. Radmila Ugrinova-Skalovska[10] is very similar to the following reconstruction made by the Yugoslav/Russian researcher Vladimir Moshin (1894–1987),[11] which is different than the reconstruction of the Bulgarian Prof. Yordan Zaimov (1921–1987). Zaimov version of the text reads as follows:[12]

† Въ лѣто Ѕ ҃Ф ҃К ҃Г ҃ отъ створенїа мира обнови сѧ съ градь зидаемъ и дѣлаемъ Їѡаном самодрьжъцемъ блъгарьскомь и помощїѫ и молїтвамї прѣс ҃тыѧ влад ҃чицѧ нашеѧ Б ҃чѧ ї въз()стѫпенїе І ҃В ҃ i връховънюю ап ҃лъ съ же градь дѣлань бысть на ѹбѣжище и на сп҃сенѥ ї на жизнь бльгаромъ начѧть же бысть градь сь Битола м ҃ца окто ҃вра въ К ҃. Конъчѣ же сѧ м ҃ца ... исходѧща съ самодрьжъць быстъ бльгарїнь родомь ѹнѹкъ Николы же ї Риѱимиѧ благовѣрьнѹ сынь Арона Самоила же брата сѫща ц ҃рѣ самодрьжавьнаго ꙗже i разбїсте въ Щїпонѣ грьчьскѫ воїскѫ ц ҃рѣ Васїлїа кде же взѧто бы злато ... фоѧ съжев ... ц҃рь разбїенъ бы ц҃рѣмь Васїлїемь Ѕ ҃Ф ҃К ҃В ҃ г. лтѣ оть створенїѧ мира ... їѹ съп() лѣтѹ семѹ и сходѧщѹ

In the year 6523 since the creation of the world [1015/1016? CE], this fortress, built and made by Ivan, Tsar of Bulgaria, was renewed with the help and the prayers of Our Most Holy Lady and through the intercession of her twelve supreme Apostles. The fortress was built as a haven and for the salvation of the lives of the Bulgarians. The work on the fortress of Bitola commenced on the twentieth day of October and ended on the [...] This Tsar was Bulgarian by birth, grandson of the pious Nikola and Ripsimia, son of Aaron, who was brother of Samuil, Tsar of Bulgaria, the two who routed the Greek army of Emperor Basil II at Stipon where gold was taken [...] and in [...] this Tsar was defeated by Emperor Basil in 6522 (1014) since the creation of the world in Klyutch and died at the end of the summer.

Significance

During the 10th century the Bulgarians established a form of national identity, that despite far from modern nationalism, helped them to survive as a distinct entity through history.[13] The inscription confirms that Tsar Samuel and his successors considered their state Bulgarian.[14] The stone plate reveals, the Cometopuli also had incipient Bulgarian ethnic consciousness.[15] The proclamation announced the first use of the Slavic title "samodŭrzhets", that means "autocrat".[16] The name of the city of Bitola, is mentioned for the first time in the inscription.[17] The Bitola inscription is a constructional one – it announces the reconstruction of a fortress. The text contains valuable information about the genealogy of the ruler Ivan. It becomes clear from it, that this ruler was the grandson of Nicholas and Ripsimia and the son of Aaron, Samuel's brother. The inscription also mentions the victory of the Bulgarians over the Byzantine emperor Basil II at the Trayanovi Vrata pass in 986, and the defeat of Samuel in the battle near the village of Klyuch in 1014.[18]

In North Macedonia, the official historiography refers to John Vladislav as one of the first Macedonian Tsars, and ruler of the "Slavic Macedonian Empire",[19] but there is no historical support for such assertions.[20] Moreover, the stone definitively reveals the ethnic self-identification of the last ruler of the First Bulgarian Empire before its conquest by Byzantium.[21] Even, according to Ugrinova-Skalovska, the claim on his Bulgarian ancestry is in accordance with the Cometopuli's insistence, to bound their dynasty to the political traditions of the Bulgarian Empire. Per Skalovska, all Western and Byzantine writers and chroniclers at that time, called the inhabitants of their kingdom Bulgarians.[22] The mainstream academics support the view that the inscription is an original artefact, made during the rule of Ivan Vladislav.[23]

Alternative views

The professor Horace Lunt, promoted the idea that the plate might have been made during the reign of Ivan Asen II ca. 1230, or that the inscription might be composed of two pieces, lettered at different times.[24] His findings are based on the photos, as well as the latex mold genuine reprint of the inscription, made by the professor Ihor Sevchenko of Dumbarton Oaks,[24] unlike the approach of Zaimovs, that created the re-print copy of the left over text, with special paper and water, when they visited Bitola in 1968.[6] Professor Lunt notes, that the Zaimov's arguments are inaccurate, stating that there are no reliable set of criteria to date early South Slavic Cyrillic. He quotes Moshin, that the date on the inscription is worn away and therefore Moshin and Zaimov "restored" most of the text inaccurately. In order for Moshin and Zaimov to restore the year of Ѕ ҃Ф ҃К ҃Г ҃ (6522–1014), they were missing the clear evidence of existence of those numbers (letters). Lunt notes that the letter " ҃Ф" (that stands for 500), can also be a "ѱ" (that stands for 700), this number is followed by a space in which the letter "M" (that stands for 40) can be fitted in, therefore the final dating of the year according to Lunt, can be 1234 – the period of the Bulgarian ruler Ivan Asen II and not Ivan Vladislav. Lunt, who is called a midwife of the Macedonian language,[25] supports also the alternative theory[26] that Samuel was a Macedonian king,[27][28][29] who ruled a separate Macedonian state,[30] with distinct Slavic Macedonian population.[31] Lunt was funded by the authorities of Yugoslavia and the Socialist Republic of Macedonia for his work.[32][33]

One of the latest approach of this problem insists also on possible pre-dating.[34] On the 23th International Congress of Byzantine Studies, (held in 2016), two archeologists: Elena Kostić and the Greek prof. Georgios Velenis, who worked on the field with the plate itself found out that, on the very top part of the plate there were holes and channels to fit Π-shaped metal joints.[35] Therefore, the plate could not have the 13th row (which was made-up by the Zaimov couple) and that it was more likely that the plate was part of much older object from the Roman period. They are giving a date close to that of Lunt, i.e. 1202–1203, when Kaloyan was Bulgarian ruler.[34] Though, both authors have summarized, most of the researchers believe that the inscription is the last written source of the First Bulgarian Empire with an accurate dating, while some others argue it is from the 13th century, and only a single study proclaims it as a forgery.[35] Some modern researchers from North Macedonia also deny the dating of the inscription, claiming the existence of the contemporary Bulgarian ethnic identification was impossible, knowing that often time Byzantines, whilst also disputing the original size of the inscription, the titles of the rulers inside the text, the specific way of invoking the saints’ help, its authenticity, etc., insisting Vladislav was Macedonian tsar.[36][37]

Criticism

The researchers presenting the thesis that the inscription was from the time of the Second Bulgarian Empire, do not give an explanation of where the Bulgarian ruler at that time, had detailed information about some events from end of the First Bulgarian Empire. It is about the kinship of the Comitopuli, as well as on some historical battles. It is not clear why this Bulgarian ruler called Ivan, who according to them was not Ivan Vladislav, pointed to be the grandson of Nikola and Ripsimia, and son of Aaron, who was Samuel's brother.[38]

Controversy

The inscription was found in SR Macedonia, then part of SFR Yugoslavia, where for political reasons any direct link between the Cometopuli and the First Bulgarian Empire was denied.[39] Originally exhibited in the local museum, the stone was locked away in 1970, after Bulgarian scientists made a rubbing and published a book on the inscription. Immediately after this publication, a big Bulgarian-Yugoslav political scandal arose. The museum director was fired for letting such a mistake happen.[40] After the collapse of Yugoslavia, the stone was re-exposed in the medieval section of the museum, but without any explanation about its text.[41] The historical and political importance of the inscription was the reason for another controversial event in the Republic of Macedonia in 2006 when the French consulate in Bitola sponsored and prepared a tourist catalogue of the town. It was printed with the entire text of the inscription on its front cover, with the word Bulgarian clearly visible on it. News about that had spread prior to the official presentation of the catalogue and was a cause for confusion among the officials of the Bitola municipality. The French consulate was warned, the printing of the new catalogue was stopped and the photo on the cover was changed.[42]

Footnotes

- Vasilka Tăpkova-Zaimova, Bulgarians by Birth: The Comitopuls, Emperor Samuel and their Successors According to Historical Sources and the Historiographic Tradition, East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450, BRILL, 2018, ISBN 9004352996, pp. 17–18.

- "Among the most significant findings of this period presented in the permanent exhibition is the epigraphic monument a marble slab with Cyrillic letters of Jovan Vladislav from 1015/17." The official site of the Institute for preservation of monuments of culture, Museum and Gallery Bitola

- Present location opposite the trade center Javor on the left side of the street Philip II of Macedonia. For more see: Chaush-Bey Mosque – one of the oldest mosques in the Balkans (demolished in 1956), on Bitola.info

- Robert Mihajlovski, Circulation of Byzantine lead seals as a contribution to the location of medieval Bitola on International Symposium of Byzantologists, Nis and Byzantyum XVIII, "800 years since the Аutocephaly of the Serbian Church (1219–2019): Church, Politics and Art in Byzantium and neighboring countries" pp. 573 – 588; 574.

- Николова, В., Куманов, М., България. Кратък исторически справочник, том 3, стр. 59.

- Камъкът на страха, филм на Коста Филипов.

- Битољска плоча из 1017 године. Македонски jазик, XVII, 1966, 51–61.

- сп. Факел. Как Йордан Заимов възстанови Битолския надпис на Иван Владислав? 3 декември 2013, автор: Василка Тъпкова-Заимова.

- „Битолския надпис на Иван Владислав, самодържец български. Старобългарски паметник от 1015 – 1016 година.", БАН. 1970 г.

- Угриновска-Скаловска, Радмила. Записи и летописи. Maкедонска книга, Скопје 1975. стр. 43–44.

- Мошин, Владимир. Битољска плоча из 1017. год. // Македонски jазик, XVII, 1966, с. 51–61

- Заимов, Йордан. Битолският надпис на цар Иван Владислав, самодържец български. Епиграфско изследване, София 1970 For criticism of this reconstruction, see: Lunt, Horace G. (1972): [review of Zaimov]. Slavic Review 31: 499.

- Crampton, R. J. A Concise History of Bulgaria (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0-521-61637-9, p. 15.

- Dennis P. Hupchick, The Bulgarian-Byzantine Wars for Early Medieval Balkan Hegemony: Silver-Lined Skulls and Blinded Armies, Springer, 2017, ISBN 3319562061, p. 314.

- Michael Palairet, Macedonia: A Voyage through History, Volume 1, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016, ISBN 1443888435, p. 245.

- Ivan Biliarsky, Word and Power in Mediaeval Bulgaria, Volume 14 of East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450, BRILL, 2011, ISBN 9004191453, p. 215.

- Room, Adrian, Placenames of the world: origins and meanings of the names for 6,600 countries, cities, territories, natural features, and historic sites, Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, ISBN 0-7864-2248-3, 2006, p. 60.

- Деница Петрова, Битолски надпис на Иван Владислав. Scripta Bulgariaca.

- An outline of Macedonian history from ancient times to 1991. Macedonian Embassy London. Retrieved on April 28, 2007.

- D. Hupchick, The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism, Springer, 2002, ISBN 0312299133, p. 53.

- Kiril Petkov, The Voices of Medieval Bulgaria, Seventh-Fifteenth Century: The Records of a Bygone Culture, BRILL, 2008, ISBN 9047433750, p. 39.

- Битолската плоча: „помлада е за околу 25 годни од Самуиловата плоча...[ок. 1018 г.] Направена е по заповед на Јоан Владислав, еден од наследниците на Самуила. …Истакнувањето на бугарското потекло од страна на Јоан Владислав е во согласност со настојувањето на Самуиловиот род да се поврзе со државноправната традиција на Симеоновото царство. Од друга страна, и западни и византиски писатели и хроничари, сите жители на царството на Петар [бугарски цар, владее од 927 до 969 г.], наследникот на бугарскиот цар Симеон, ги наречувале Бугари." Дел од содрината на плочата, според преводот на Скаловска:„Овој град [Битола] се соѕида и се направи од Јоан самодржец [цар] на бугарското (блъгарьскаго) цраство... Овој град (крепост) беше направен за цврсто засолниште и спасение на животот на Бугарите (Блъгаромь)... Овој цар и самодржец беше родум Бугарин (Блъгарїнь), тоест внук на благоверните Никола и Рипсимија, син на Арона, постариот брат на самодржавниот цар Самуил..." (Р.У. Скаловска, Записи и летописи. Скопје 1975. 43–44.)

-

- Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, Dimitar Bechev, Scarecrow Press, 2009 ISBN 0810855658, p. 195.

- Reuter, Timothy, ed. (2000). The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 3, c.900–c.1024. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 600. ISBN 9781139055727..

- The legend of Basil the Bulgar-slayer, Paul Stephenson, Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-521-81530-4, pp. 29–30.

- Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250, Cambridge medieval textbooks, Florin Curta, Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-521-81539-8, p. 246.

- Basil II and the governance of Empire (976–1025), Oxford studies in Byzantium, Catherine Holmes, Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-19-927968-3, pp. 56–57.

- Das makedonische Jahrhundert: von den Anfängen der nationalrevolutionären Bewegung zum Abkommen von Ohrid 1893–2001; ausgewählte Aufsätze, Stefan Troebst, Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2007, ISBN 3-486-58050-7, S. 414.

- Krieg und Kriegführung in Byzanz: Die Kriege Kaiser Basileios II. Gegen die Bulgaren (976–1019), Paul Meinrad Strässle, Böhlau Verlag Köln Weimar 2006, ISBN 341217405X, p. 172.

- Византийский временник, Институт истории (Академия наук СССР), Институт славяноведения и балканистики (Академия наук СССР), Институт всеобщей истории (Российская академия наук) Изд-во Академии наук СССР, 1973, стр. 266.

- Bŭlgarski ezik, Institut za bŭlgarski ezik (Bŭlgarska akademiia na naukite) 1981, p. 372.

- Срђан Пириватрић, „Самуилова држава. Обим и карактер", Византолошки институт Српске академије науке и уметности, посебна издања књига 21, Београд, 1997, стр. 183.

- Ivan Vladislav. In Prosopographie der mittelbyzantinischen Zeit (2013). Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- Иван Микулчиќ, Средновековни градови и тврдини во Македонија. (Македонска академија на науките и уметностите — Скопје, 1996), стр. 140–141.

- Horace Lunt, Review of "Bitolski Nadpis na Ivan Vladislav Samodurzhets Bulgarski: Starobulgarski Pametnik ot 1015–1016 Godina" by Iordan Zaimov and Vasilka Zaimova, Slavic Review, vol. 31, no. 2 (Jun. 1972), p.499

- James Franklin Clarke Jr., The Pen and the Sword: Studies in Bulgarian History, edited by Dennis P. Hupchick, Boulder: East European Monographs ; New York: Distributed by Columbia University Press, 1988.

- Michael Palairet, Macedonia: A Voyage through History (Vol. 1, From Ancient Times to the Ottoman Invasions), Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016; ISBN 1443888435, p. 245.

- Rossos, Andrew (June 6, 2008). Macedonia and the Macedonians: A History. Hoover Institution. p. 30. ISBN 9780817948825.

- Antoljak, Stjepan (1985). Samuel and his state. Skopje: Macedonian Review Editions.

- Pop-Atanasov, Gjorgi (2017). Occasional papers on Religion in Eastern Europe. Volume 37, Issue 4: Ohrid Literary School in the Period of Tzar Samoil and the Beginnings of the Russian Church Literature. Portland, Oregon: George Fox University.

- Horace G. Lunt, Old Church Slavonic Grammar, edition 7, Walter de Gruyter, 2010; ISBN 3110876884, pp. 2-3.

- C. Bartusis, Mark (1992). The Late Byzantine Army: Arms and Society, 1204–1453. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 64, 256.

- Lunt, Horace (1952). A Grammar of the Macedonian Literary Language. Državno knigoizdatelstvo na NR Makedonija. pp. XII. ISBN 9786082181608.

Finally, I wish to thank the Yugoslav Council for Science and Culture and the Macedonian Ministry of Education, Science and Culture for the financial aid which they granted me, thus enabling me to prolong my stay in Macedonia and study the language more thoroughly.

- Horace G. Lunt and the beginning of Macedonian studies in the United States of America (Victor A. Friedman), p. 117.

- Georgios Velenis, Elena Kostić (2017). Texts, Inscriptions, Images: The Issue of the Pre-Dated Inscriptions in Contrary with the Falsified. The Cyrillic Inscription from Edessa. Sofia: Институт за изследване на изкуствата, БАН. pp. 113–127. ISBN 978-954-8594-65-3.

- Georgios Velenis, Elena Kostić (2016). Proceedings of the 23rd International Congress of Byzantine Studies. Belgrade: The Serbian National Committee of AIEB and the contributors 2016. p. 128. ISBN 978-86-83883-23-3.

- Mitko B. Panov, The Blinded State: Historiographic Debates about Samuel Cometopoulos and His State (10th–11th Century); BRILL, 2019, ISBN 900439429X, p. 74.

- Стојков, Стојко (2014) Битолската плоча – дилеми и интерпретации. Во: Самуиловата држава во историската, воено-политичката, духовната и културната традиција на Македонија, 24–26 октомври 2014, Струмица, Македонија.

- Georgi Mitrinov, Contributions of the Sudzhov family to the preservation of Bulgarian cultural and historic heritage in Vardar Macedonia, Sofia University St. Kliment Ohridski, language; Bulgarian, Journal: Българска реч. 2016, Issue No: 2, pp. 104–112.

- Who are the Macedonians? Hugh Poulton, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2000, ISBN 1850655340, p. 20.

- Камъкът на страха – филм на Коста Филипов – БНТ.

- J. Pettifer ed., The New Macedonian Question, St Antony's Series, Springer, 1999, ISBN 0230535798, p. 75.

- Исправена печатарска грешка, Битола за малку ќе се претставуваше како бугарска. Дневник-online, 2006.Archived February 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

References

- Божилов, Иван. Битолски надпис на Иван Владислав // Кирило-методиевска енциклопедия, т. І, София, 1985, с. 196–198. (in Bulgarian)

- Бурмов, Александър. Новонамерен старобългарски надпис в НР Македония // сп. Пламък, 3, София, 1959, 10, с. 84–86. (in Bulgarian)

- Заимов, Йордан. Битолски надпис на Иван Владислав, старобългарски паметник от 1015–1016 // София, 1969. (in Bulgarian)

- Заимов, Йордан. Битолският надпис на цар Иван Владислав, самодържец български. Епиграфско изследване // София, 1970. (in Bulgarian)

- Заимов, Йордан. Битольская надпись болгарского самодержца Ивана Владислава, 1015–1016 // Вопросы языкознания, 28, Москва, 1969, 6, с. 123–133. (in Russian)

- Мошин, Владимир. Битољска плоча из 1017. год. // Македонски jазик, XVII, Скопје, 1966, с. 51–61 (in Macedonian)

- Мошин, Владимир. Уште за битолската плоча од 1017 година // Историја, 7, Скопје, 1971, 2, с. 255–257 (in Macedonian)

- Томовић, Г. Морфологиjа ћирилских натписа на Балкану // Историjски институт, Посебна издања, 16, Скопје, 1974, с. 33. (in Serbian)

- Џорђић, Петар. Историја српске ћирилице // Београд, 1990, с. 451–468. (in Serbian)

- Mathiesen, R. The Importance of the Bitola Inscription for Cyrilic Paleography // The Slavic and East European Journal, 21, Bloomington, 1977, 1, pp. 1–2.

- Угринова-Скаловска, Радмила. Записи и летописи // Скопје, 1975, 43–44. (in Macedonian)

- Lunt, Horace. On dating Old Church Slavonic bible manuscripts. // A. A. Barentsen, M. G. M. Tielemans, R. Sprenger (eds.), South Slavic and Balkan linguistics, Rodopi, 1982, p. 230.

- Georgios Velenis, Elena Kostić, (2017). Texts, Inscriptions, Images: The Issue of the Pre-Dated Inscriptions in Contrary with the Falsified. The Cyrillic Inscription from Edessa.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Inscription of Bitola. |

- Macedonian Question

- Macedonism