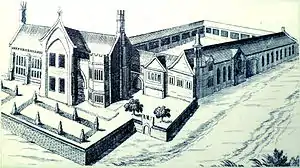

Blackfriars, Gloucester

Blackfriars, Gloucester, England, founded about 1239,[1] is one of the most complete surviving Dominican black friaries in England.[2] Now owned by English Heritage and restored in 1960, it is currently leased to Gloucester City Council and used for weddings, concerts, exhibitions, guided tours, filming, educational events and private hires. The former church, since converted into a house, is a Grade I listed building. [3]

History

The Monastery, known as Blackfriars from the black cloaks the friars wore, was founded on a site west of Southgate Street, with the city wall adjacent to the south. It comprised a church and a quadrangle formed by such buildings as the scriptorium (library), the dormitory with its renowned scissor-braced roof and the cloisters. It was established around 1239 under the patronage of Henry III and at its height was home to 30-40 friars.

The friary went into private hands after the Dissolution of the Monasteries, having been purchased for £240 in 1539 by Thomas Bell (died 1566), who converted the church to his residence and transformed the buildings of the cloister, including the scriptorium, into a cap manufactory.

The conversion of the church into a grand mansion was completed by 1545,[4] which Bell referred to in his will as "My howse called Bell Place".[5] The nave and chancel were shortened approximately each by a half, either side of the central crossing, of which latter the southern member, extending into the cloister, was removed. Upper floors and stone mullioned windows were added above the outer aisles, a semi-circular bay window being also added to the north side of the nave. The great window at the north end of the northern transept was built in, and replaced with several smaller windows.[6] In 1555 John Hooper, the Bishop of Gloucester, was burnt to death for his beliefs.[7] His widow, Anne Hooper and other Blackfriars clergy were exiled abroad. Hooper and her daughter, Rachel, died in Frankfurt in 1555 of the plague.[8] Anne left money to her son.[9]

A 1721 image of the complex by William Stukeley provides valuable information about the friary at that time.

In the 1930s Bell Place was converted into 2 dwellings. Restoration work on this former church was completed in 1984, when it was opened to the public.[10]

The cloister buildings were converted from former cap factory into dwellings in the 18th century, and part of the west range was heightened and converted into three houses. Bell bequeathed Blackfriars to his niece Joan and her husband Thomas Denys, son of Sir Walter Denys of Dyrham Park, in which family it remained until c. 1700. Both the ancient gateways to the Blackfriars have been removed, one before 1724, the other having collapsed c. 1750. One had become known as Lady Bell's Gate, which is memorialised in the modern street name "Ladybellegate", onto which the western cloister faces.

The site is today the most complete surviving Dominican priory in Britain, containing the oldest surviving purpose-built library in the country.[11] The friary includes a notable fine, scissor-braced, dormitory roof.[2]

References

- William Page (editor) (1907). "Friaries: Gloucester". A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 2. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 5 January 2012.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Blackfriars, English Heritage, 2011. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- "Name: BLACKFRIARS CHURCH AND PART OF EAST RANGE OF FRIARY List entry Number: 1245989". Historic England. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- A lease dated 1545 to Thomas Bell by Gloucester Corporation refers to "his mansion place new built...lately called the black friars and now Bell Place being of the yearly value of £9". Glos. Archives GBR/J/3/18 ff.44v-45.

- Will of Sir Thomas Bell the Elder: Glos. Archives, 1566/150.

- Alterations as described by VCH Glos, vol.4 & from comparison with an illustration of a theoretical reconstruction by Terry Ball.

- Rachel Basch, ‘Hooper, Anne (d. 1555)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, April 2016 accessed 7 June 2017

- J. Chappell; K. Kramer (19 November 2014). Women during the English Reformations: Renegotiating Gender and Religious Identity. Springer. pp. 47–48. ISBN 978-1-137-46567-2.

- Ben Lowe (2 March 2017). Commonwealth and the English Reformation: Protestantism and the Politics of Religious Change in the Gloucester Vale, 1483–1560. Routledge. pp. 297–. ISBN 978-1-351-95038-1.

- "Mary in Monmouth: Gloucester Blackfriars (2) and Newport (Novus Burgo-Castell Newydd ar Wsg)". maryinmonmouth.blogspot.com. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- VisitBritain website Archived 12 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Blackfriars, Gloucester. |