Blue Collar (film)

Blue Collar is a 1978 American crime drama film directed by Paul Schrader, in his directorial debut. Written by Schrader and his brother Leonard, the film stars Richard Pryor, Harvey Keitel and Yaphet Kotto.[3] The film is both a critique of union practices and an examination of life in a working-class Rust Belt enclave. Although it has minimal comic elements provided by Pryor, it is mostly dramatic.

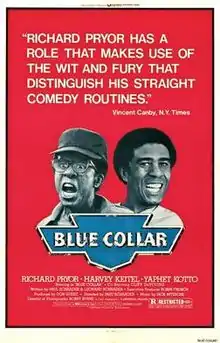

| Blue Collar | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Paul Schrader |

| Produced by | Don Guest |

| Written by | Paul Schrader Leonard Schrader |

| Based on | an article by Sydney A. Glass |

| Starring | Richard Pryor Harvey Keitel Yaphet Kotto |

| Music by | Jack Nitzsche |

| Cinematography | Bobby Byrne |

| Edited by | Tom Rolf |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 114 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.7 million[1] |

| Box office | $6.5 million[2] |

Schrader, who was a screenwriter renowned for his work on Taxi Driver (1976), recalls the shooting as being very difficult because of the artistic and personal tensions he had with the actors (including the stars themselves). Schrader has also stated that while making the film, he suffered an on-set mental breakdown, which made him seriously reconsider his career.[4]

The film was shot in Detroit and Kalamazoo, Michigan.

Plot

A trio of Wayne County, Michigan auto workers, two black—Ezekiel "Zeke" Brown from Detroit, Michigan (Pryor) and two-time ex-con convicted murderer Smokey James from Mississippi who spent time in Michigan State Prison (Kotto)—and one white— Polish-American from Hamtramck, Michigan, Jerry Bartowski (Keitel)—are fed up with mistreatment at the hands of both management and union brass. Smokey is in debt to a loan shark over a numbers game, Jerry works a second job as a gas station attendant to get by and finds himself unable to pay for the orthodontics work that his daughter needs, and Zeke commits tax evasion by filing false claims to the IRS in order to improve his family's income.[5]

Coupled with the financial hardships on each man's end, the trio hatch a plan to rob a safe at United Auto Workers union headquarters. They commit the caper but find only a few scant bills in the process. More importantly, they also come away with a ledger which contains evidence of the union's illegal loan operation and ties to organized crime syndicates in Las Vegas, Nevada, Chicago, Illinois and New York City, New York. They attempt to blackmail the union with the information but the union retaliates strongly and begins to turn the tables on the three friends. A suspicious accident at the plant results in Smokey's death that is investigated as a work accident caused by negligent safety protocols, which Zeke and Jerry realize was a murder coordinated by the union bosses in retaliation for the trio's blackmail.

A FBI agent John Burrows attempts to coerce Jerry into material witness on the union's corruption, which would make him an adversary of his co-workers as well as the union bosses. At the same time, corrupt union bosses succeed in coopting Zeke to work for them with promises of upward mobility being promoted to shop steward and increased remuneration. Zeke, happy with his new duties and higher pay, pragmatically prescinds from seeking justice for Smokey's murder, as it would jeopardize his newfound standing within the ranks of the union. Jerry attempts to convince Zeke to take steps to avenge Smokey's death, but Zeke rebukes him, telling Jerry that nothing will bring Smokey back and that they should just move forward. Disgusted with Zeke's capitulation, Jerry decides to cooperate with the FBI and a United States Congress Select or special committee (United States Congress) that have been investigating the union. Two gunmen, hired by Zeke try to shoot Jerry in a drive-by shooting when in the Detroit–Windsor tunnel but Jerry crashes his car and is rescued by the police. In the end, Zeke confronts Jerry, as Jerry enters the plant with federal agents. Once friends, Jerry and Zeke now turn on each other, and attack each other, confirming the prescient earlier narrative that union corruption divides workers against one another.

Cast

- Richard Pryor as Zeke Brown

- Harvey Keitel as Jerry Bartowski

- Yaphet Kotto as Smokey James

- Ed Begley Jr. as Bobby Joe

- Harry Bellaver as Eddie Johnson

- George Memmoli as Jenkins

- Lucy Saroyan as Arlene Bartowski

- Lane Smith as Clarence Hill

- Cliff DeYoung as John Burrows

- Borah Silver as Dogshit Miller

- Chip Fields as Caroline Brown

- Harry Northup as Hank

- Leonard Gaines as Mr Berg, IRS Man

- Milton Selzer as Sumabitch

- Sammy Warren as Barney

- Jimmy Martinez as Charlie T. Hernandez

Production

The film was shot on location at the Checker plant in Kalamazoo, Michigan and at locales around Detroit, including the Ford River Rouge Complex on the city's southwest side and the MacArthur Bridge to Belle Isle.

The three main actors did not get along and were continually fighting throughout the shoot. The tension became so great that at one point Richard Pryor (supposedly in a drug-fueled rage) pointed a gun at Schrader and told him that there was "no way" that he would ever to do more than three takes for a scene, an incident that may have caused Schrader's nervous breakdown.[4]

Schrader states that during the filming of one take, Harvey Keitel became so irritated by Pryor's lengthy improvisations that he flung the contents of an ashtray into the camera lens, ruining the take. Pryor and his bodyguard responded by pinning Keitel to the floor and pummeling him with their fists.[6]

Jack Nitzsche's blues-flavored score includes "Hard Workin' Man", a collaboration with Captain Beefheart.[7]

Reception

Blue Collar was universally praised by critics. The film holds a 100% "Fresh" rating on the review aggregate website Rotten Tomatoes.[8] Both Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel lauded the film; Ebert awarded the film four stars[9] and Siskel placed the film fourth on his list of the ten best of 1978.[10]

Filmmaker Spike Lee included the film on his essential film list "Films All Aspiring Filmmakers Must See".[11] The New York Times placed the film on its Best 1000 Movies Ever list.[12]

In his autobiography Born to Run, Bruce Springsteen names Blue Collar and Taxi Driver as two of his favorite films of the 1970s.[13]

See also

References

- Kilday, Gregg (Apr 6, 1977). "Writing His Way to the Top". Los Angeles Times. p. e20.

- "Blue Collar Box Office Information". Box Office Mojo.

- "Blue Collar". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- The Back Row, Robin's Underrated Gems: Blue Collar (1978)

- Schrader, Paul. "Blue Collar | Film Review | Spirituality & Practice". www.spiritualityandpractice.com.

- Henry, David; Henry, Joe (2014-01-01). Furious Cool: Richard Pryor and the World That Made Him. Algonquin Books. ISBN 978-1-61620-447-1.

- Metz, Nina (August 24, 2017). "No shadows or trenchcoats: Why a 1978 Richard Pryor movie unexpectedly qualifies as film noir". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- Blue Collar, Movie Reviews. Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- Roger Ebert reviews Blue Collar. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- Siskel and Ebert Top 10. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- List of Films All Aspiring Filmmakers Must See. IndieWire. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made. The New York Times via Internet Archive. Published April 29, 2003. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- Springsteen, Bruce (2016). Born to Run. London: Simon & Schuster. p. 313.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Blue Collar (film) |