Bluntnose stingray

The bluntnose stingray or Say's stingray (Dasyatis say, often misspelled sayi) is a species of stingray in the family Dasyatidae, native to the coastal waters of the western Atlantic Ocean from the U.S. state of Massachusetts to Venezuela. It is a bottom-dwelling species that prefers sandy or muddy habitats 1–10 m (3.3–32.8 ft) deep, and is migratory in the northern portion of its range. Typically growing to 78 cm (31 in) across, the bluntnose stingray is characterized by a rhomboid pectoral fin disc with broadly rounded outer corners and an obtuse-angled snout. It has a whip-like tail with both an upper keel and a lower fin fold, and a line of small tubercles along the middle of its back.

| Bluntnose stingray | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | Myliobatiformes |

| Family: | Dasyatidae |

| Genus: | Dasyatis |

| Species: | D. say |

| Binomial name | |

| Dasyatis say (Lesueur, 1817) | |

| |

| Range of the bluntnose stingray | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

.jpg.webp)

External anatomy of a male bluntnose stingray

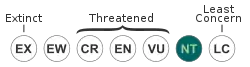

More active at night than during the day when it is usually buried in sediment, the bluntnose stingray is a predator of small benthic invertebrates and bony fishes. This species is aplacental viviparous, in which the unborn young are nourished initially by yolk, and later histotroph ("uterine milk") produced by their mother. Females give birth to 1–6 pups every May after a gestation period of 11–12 months, most of which consists of a period of arrested embryonic development. The venomous tail spine of the bluntnose stingray is potentially dangerous to unwary beachgoers. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has listed this species as near threatened.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

French naturalist Charles Alexandre Lesueur originally described the bluntnose stingray from specimens collected in Little Egg Harbor off the U.S. State of New Jersey. He published his account in an 1819 volume of the Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, and named the new species Raja say in honor of Thomas Say, one of the founding members of the Academy.[2][3] The species was moved to the genus Dasyatis by subsequent authors. In 1841, German biologists Johannes Peter Müller and Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle erroneously gave the specific epithet as sayi in their Systematische Beschreibung der Plagiostomen, which thereafter became the typical spelling used in literature.[1][2] Recently, there has been a push to use the correct original spelling again, though it has also been proposed that the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) officially emend the spelling to sayi, for consistency with previous usage.[1][4]

Lisa Rosenberger's 2001 phylogenetic analysis, based on morphological characters, found that the bluntnose stingray is one of the more basal members of its genus, and that it is a sister species to the diamond stingray (D. dipterura) of the western Pacific Ocean. The two species likely diverged before or with the formation of the Isthmus of Panama, some three million years ago.[5]

Distribution and habitat

The bluntnose stingray is found in the western Atlantic Ocean, from Long Island, New York southward through the Florida Keys, the northern Gulf of Mexico, and the Greater and Lesser Antilles; on rare occasions it is found as far north as Massachusetts, as far south as Venezuela, and as far west as Mexico. It is absent from the southern Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean coast of Central America.[1][6] Reports of this species from off Brazil and Argentina likely represent misidentifications of the groovebelly stingray (D. hypostigma).[1]

Common in coastal habitats such as bays, lagoons, and estuaries, the bluntnose stingray is a bottom-dwelling species usually found at a depth of 1–10 m (3.3–32.8 ft), though it has been recorded from as deep as 20 m (66 ft). It frequents sandy or muddy flats, preferring water with a salinity of 25–43 ppt and a temperature of 12–33 °C (54–91 °F).[1][7][8] Adult bluntnose stingrays are seldom found in seagrass meadows or shoals, though the latter serves as a habitat for young rays. Along the U.S. East Coast, schools of bluntnose stingrays migrate long distances northward into bays and estuaries to spend the summer, and move back to southern offshore waters for winter.[9][10]

Description

The bluntnose stingray has a diamond-shaped pectoral fin disc about a sixth wider than long, with broadly rounded outer corners. The leading margins of the disc are nearly straight and converge at the tip of the snout at up to a 130° angle; the anterior disc shape distinguishes this species from the similar Atlantic stingray (D. sabina), which has a longer, more acute snout. The mouth is curved, with a central projection on the upper jaw that fits into an indentation on the lower jaw. There is a row of five papillae across the floor of the mouth, with the outermost pair smaller and set apart from the others. There are 36–50 upper tooth rows; the teeth have quadrangular bases and are arranged with a quincunx pattern into flattened surfaces. The tooth crowns are rounded in females and juveniles, while those of males in breeding condition are triangular and pointed. The pelvic fins are triangular with rounded tips.[6][11]

The whip-like tail measures over one and a half times as long as the disc and bears one or two long, serrated stinging spines on top, about a quarter of the tail length back from the base.[6][12] The second spine, if present, is a replacement that periodically grows in front of the existing spine.[13] Behind the spine, there are well-developed upper and lower fin folds, with the lower fold longer and wider than the upper. Small thorns or tubercles are found in a midline row from behind the eyes to the base of the tail spine, increasing in number with age. Adults also have prickles before and behind the eyes and on the outer parts of the disc. The dorsal coloration is grayish, reddish, or greenish brown; some individuals also possess bluish spots, are darker towards the sides and rear, or have a thin white disc margin. The ventral surface is whitish, sometimes with a dark disc margin or dark blotches.[6][7][11] A record off French Guiana gives the maximum disc width of this species as 1 m (3.3 ft), but that specimen may have been misidentified and other sources give a maximum disc width of no more than 0.78 m (2.6 ft).[10] Females grow larger than males.[7]

Biology and ecology

The bluntnose stingray has generally nocturnal habits and spends much of the day buried in the substrate.[10][14] It has been known to follow the rising tide to forage in water barely deep enough to cover its body.[15] This species preys upon small invertebrates, including crustaceans, annelid worms, and bivalve and gastropod molluscs, and bony fishes.[7] It mainly targets benthic and burrowing organisms, but also opportunistically takes free-swimming prey. In Delaware Bay, this species feeds predominantly on the shrimp Cragon septemspinosa and the blood worm Glycera dibranchiata, and its overall dietary composition is virtually identical to that of the roughtail stingray (D. centroura), with which it shares the bay.[14] The bluntnose stingray is preyed upon by larger fishes such as the bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas).[7] Known parasites of this species include the tapeworms Acanthobothrium brevissime and Kotorella pronosoma,[16][17] the monogenean Listrocephalos corona,[18] and the trematodes Monocotyle pricei and Multicalyx cristata.[19][20]

Like other stingrays, the bluntnose stingray is aplacental viviparous. with the embryos initially sustained by yolk. Later in development, finger-like extensions of the uterine epithelium called "trophonemata" surround the embryo and deliver protein and lipid-rich histotroph ("uterine milk") produced by the mother.[10][21] Only the left ovary and uterus in adult females are functional.[22] Mating occurs during a well-defined period from April to June, peaking in May, with the males presumably using their pointed teeth to grasp the females for copulation.[7][10] However, embryonic development halts at the blastoderm stage, shortly after the formation of the zygote, and does not resume for approximately ten months. In the spring of the following year, the embryos rapidly mature over a period of 10–12 weeks. This period of embryonic diapause may reflect the greater availability of food in the spring.[10][23]

Including the extended period of diapause, the gestation period lasts around 11–12 months, with 1–6 young being born in mid to late May.[1][7][23] In 1941, in a shallow channel between Chincoteague Island and Cape Charles, Virginia, several large bluntnose stingrays were observed repeatedly breaking the surface and swimming rapidly in straight lines, some with their tails thrashing in the air; others were seen rising slowly to the surface and "hanging" for several minutes. One of the rays was hooked and the shock of capture caused it to release five near-term fetuses, suggesting that this activity may have been related to parturition. The aborted young were pale with small yolk sacs, and a swelling in the place of their tail spines.[22] Females begin ovulating a new batch of eggs immediately after giving birth, indicating that they have an annual reproductive cycle.[10] Newborn rays measure 15–17 cm (5.9–6.7 in) across and weigh 170–250 g (6.0–8.8 oz). Males mature sexually at disc width of 30–36 cm (12–14 in) and a weight of 3–6 kg (6.6–13.2 lb), while females mature at a disc width of 50–54 cm (20–21 in) and a weight of 7–15 kg (15–33 lb).[1][7]

Human interactions

The bluntnose stingray is not aggressive, though it will defend itself if stepped on or otherwise incited. Its tail spine can inflict an excruciating injury, and can easily pierce leather or rubber footwear.[3][7] The paralytic venom delivered may have potentially life-threatening effects on those with heart or respiratory problems, and is the subject of biomedical and neurobiological research.[24] This species is popular with ecotourist divers.[7] Abundant and widespread, the bluntnose stingray is caught incidentally by commercial trawl and gillnet fisheries operating in nearshore U.S. waters; these activities are not a threat to its population, as most captured rays are released alive. The impact of fishing in the southern parts of its range is uncertain, but is unlikely to significantly affect the species as a whole as these activities occur outside its centers of distribution. The International Union for Conservation of Nature has listed the bluntnose stingray as near threatened.[1]

References

- Carlson, J., Charvet, P., Blanco-Parra, MP, Briones Bell-lloch, A., Cardenosa, D., Derrick, D., Espinoza, E., Herman, K., Morales-Saldaña, J.M., Naranjo-Elizondo, B., Pacoureau, N., Schneider, E.V.C. & Simpson, N.J. (2020). "Hypanus say". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2021.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eschmeyer, W.N. and R. Fricke (eds). say, Raja Archived 2012-02-21 at the Wayback Machine. Catalog of Fishes electronic version (January 15, 2010). Retrieved on February 17, 2010.

- Smith, H.M. (1907). The Fishes of North Carolina. E.M. Uzzell & Co. pp. 44–45.

- Santos, S.; H. Ricardo & M.R. de Carvalho (June 30, 2008). "Raja say Le Sueur, 1817 (currently Dasyatis say; Chondrichthyes, Myliobatiformes, DASYATIDAE): proposed change of spelling to Raja sayi Le Sueur, 1817". Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 65 (Part 2): 119–123. doi:10.21805/bzn.v65i2.a14.

- Rosenberger, L.J.; Schaefer, S. A. (August 6, 2001). Schaefer, S. A. (ed.). "Phylogenetic Relationships within the Stingray Genus Dasyatis (Chondrichthyes: Dasyatidae)". Copeia. 2001 (3): 615–627. doi:10.1643/0045-8511(2001)001[0615:PRWTSG]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 1448284.

- McEachran, J.D. & J.D. Fechhelm (1998). Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico: Myxiniformes to Gasterosteiformes. University of Texas Press. pp. 179–180. ISBN 0-292-75206-7.

- Collins, J. Biological Profiles: Bluntnose Stingray. Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. Retrieved on January 14, 2010.

- Lippson, A.J. & R.L. Lippson (1997). Life in the Chesapeake Bay (second ed.). JHU Press. pp. 174–175. ISBN 0-8018-5475-X.

- Walker, S.M. (2003). Rays. Lerner Publications. p. 29. ISBN 1-57505-172-9.

- Snelson, F.F. (Jr.); S.E. Williams-Hooper & T.H. Schmid (1989). "Biology of the bluntnose stingray, Dasyatis sayi, in Florida coastal lagoons". Bulletin of Marine Science. 45 (1): 15–25.

- Bean, T.H. (1903). Catalogue of the Fishes of New York. University of the State of New York. pp. 55–56.

- McClane, A.J. (1978). McClane's Field Guide to Saltwater Fishes of North America. Macmillan. pp. 40–41. ISBN 0-8050-0733-4.

- Teaf, C.M. & T.C. Lewis (February 11, 1987). "Seasonal Occurrence of Multiple Caudal Spines in the Atlantic Stingray, Dasyatis sabina (Pisces: Dasyatidae)". Copeia. 1987 (1): 224–227. doi:10.2307/1446060. JSTOR 1446060.

- Hess, P.W. (June 19, 1961). "Food Habits of Two Dasyatid Rays in Delaware Bay". Copeia. 1961 (2): 239–241. doi:10.2307/1440016. JSTOR 1440016.

- Lythgoe, J. & G. Lythgoe (1991). Fishes of the Sea: The North Atlantic and Mediterranean. MIT Press. p. 43. ISBN 0-262-12162-X.

- Holland, N.D. & N.G. Wilson (2009). "Molecular identification of larvae of a tetraphyllidean tapeworm (Platyhelminthes: Eucestoda) in a razor clam as an alternative intermediate host in the life cycle of Acanthobothrium brevissime". Journal of Parasitology. 95 (5): 1215–1217. doi:10.1645/GE-1946.1. PMID 19366282.

- Palm, H.W.; A. Waeschenbach & D.T.J. Littlewood (June 2007). "Genetic diversity in the trypanorhynch cestode Tentacularia coryphaenae Bosc, 1797: evidence for a cosmopolitan distribution and low host specificity in the teleost intermediate host" (PDF). Parasitology Research. 101 (1): 153–159. doi:10.1007/s00436-006-0435-1. PMID 17216487. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-14.

- Bullard, S.A.; R.R. Payne & J.S. Braswell (December 2004). "New genus with two new species of capsalid monogeneans from dasyatids in the Gulf of California" (PDF). Journal of Parasitology. 90 (6): 1412–1427. doi:10.1645/GE-304R. PMID 15715238. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-02-21.

- Hargis W.J. (Jr.) (1955). "Monogenetic trematodes of Gulf of Mexico fishes. Part IV. The superfamily Capsaloidea Price, 1936". Transactions of the American Microscopical Society. 74 (3): 203–225. doi:10.2307/3224093. JSTOR 3224093.

- Hendrix, S.S. & R.M. Overstreet (October 1977). "Marine Aspidogastrids (Trematoda) from Fishes in the Northern Gulf of Mexico". The Journal of Parasitology. 63 (5): 810–817. doi:10.2307/3279883. JSTOR 3279883. PMID 915610.

- Wourms, J.P. (1981). "Viviparity: The maternal-fetal relationship in fishes". American Zoologist. 21 (2): 473–515. doi:10.1093/icb/21.2.473.

- Hamilton W.J. (Jr.) & R.A. Smith (September 30, 1941). "Notes on the Sting-Ray, Dasyatis say (Le Sueur)". Copeia. 1941 (3): 175. doi:10.2307/1437744. JSTOR 1437744.

- Morris, J.A., J. Wyffels, F.F. Snelson (Jr.) (1999). "Confirmation of embryonic diapause in the bluntnose stingray Dasyatis say". Abstract from the American Elasmobranch Society 1999 Annual Meeting, State College, Pennsylvania.

- Farren, R. (2003). Highroad Guide to Florida Keys and the Everglades. John F. Blair. p. 266. ISBN 0-89587-280-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bluntnose stingray. |