Brooke Mansion (Birdsboro, Pennsylvania)

The Edward Brooke II Mansion (1887–88), also known as "Brookeholm," is a Queen Anne country house at 301 Washington Street in Birdsboro, Pennsylvania.[1]:284 Designed by architect Frank Furness and completed in 1888, it was Edward Brooke II's wedding present to his bride, Anne Louise Clingan.[2]:60

| Edward Brooke II Mansion | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Queen Anne |

| Address | 301 Washington Street |

| Town or city | Birdsboro, Pennsylvania |

| Coordinates | 40°15′38.2″N 75°48′44.7″W |

| Construction started | 1887 |

| Completed | 1888 |

| Renovated | 1893 |

| Technical details | |

| Material | brownstone block wood shingles |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Frank Furness |

| Architecture firm | Furness, Evans & Company |

| Main contractor | Levi H. Focht Company |

| Website | |

| www | |

Five years later, Edward II himself designed a major addition to the mansion.[3]:224 Following their parents' deaths, the Brooke children sold the property in the 1940s.[3]:225 The mansion served as a nursing home for thirty years, and recently as a bed and breakfast.[3]:225

The property spent fourteen years on and off the real estate market, before being sold at auction on September 29, 2018, for $572,000.[4]

Brooke family

Birdsboro was named for ironmaker William Bird, who established a forge near the mouth of Hay Creek, about 1740.[5] In 1771, his son Marcus founded Hopewell Furnace, on Hay Creek about five miles upstream.[5] By the time of the Revolutionary War, Marcus Bird was the largest American producer of iron.[5][lower-alpha 1] He cast iron cannon, shot and shell for the Continental Army, and served in the Pennsylvania Militia.[7] In the post-war depression he lost both forges to creditors in 1788.[5] The creditors hired John Louis Barde to operate the forges, and Barde purchased the Birdsboro forge in 1796.[5] He hired Matthew Brooke III to assist him, and after Barde's 1799 death Matthew continued to operate the forges for Barde's widow.[5] In 1800, Matthew's father and uncles formed Brooke & Buckley and bought the Hopewell forge, with Matthew's brother Clement in charge.[lower-alpha 2] In 1805, at age 43, Matthew married Barde's 17-year-old daughter Elizabeth.[10]

Matthew and Elizabeth Brooke had five children, three of whom lived to adulthood: Edward (1816–1878); George (1818–1912); and Elizabeth Mary (1825–1870).[lower-alpha 3] Matthew died in 1827 and Elizabeth in 1828, leaving their orphaned children under the guardianship of Matthew's brother Clement. The Birdsboro forge was leased out to Brooke & Buckley until Edward and George attained their majorities. The Schuylkill Canal (completed 1825) passed through Birdsboro and, prior to railroads, was the primary means of transporting anthracite coal to Philadelphia and elsewhere.[13] The young brothers took charge of the business in 1837, and diversified its holdings.[lower-alpha 4] They modernized the furnaces to run on anthracite (instead of charcoal), expanded their businesses, and consolidated them in 1867 as the Birdsboro Iron Forge Company.[13] The Reading Railroad and the Pennsylvania Railroad both built lines through Birdsboro. The Brookes were behind the building of the Wilmington & Northern Railroad, a subsidiary of the Reading Company, that connected to their iron ore mines, and continued south to Wilmington, Delaware.[14] Edward served as the railroad's first president.[13] After their sister's 1870 death, the brothers bought out her interest and split the company into two entities – the E. & G. Brooke Land Company (coal and iron ore mines) and the E. & G. Brooke Iron Company (iron and steel manufacture).[5] The E. & G. Brooke Iron Company became Birdsboro Steel in 1905.[13]:998

Both Brooke brothers were keenly interested in architecture, and were clients of Frank Furness. Edward built a Greek Revival mansion, "Brooke Manor" (1844, demolished 1968) on a hill overlooking the town.[3] In the mid-1870s, he hired Furness to modernize and expand it.[15] George designed and oversaw construction of St. Michael's Episcopal Church, in the early 1850s.[lower-alpha 5] Twenty years later, he did the same for its Sunday school building (1872–73), which he and his brother donated.[16]:30–31 George designed his own Second Empire mansion, "Brookewood" (1860, burned 1917), and its many additions.[3]:225 After Edward's 1878 death, George selected Furness to design a major expansion of St. Michael's Church, 1884–85.[1]:262–63 This included the addition of transepts, a chancel and choir, a bell tower, and new church furniture (possibly executed by Daniel Pabst).[16]:32 George again oversaw the project, and he and his family paid for the expansion.[16]:33 The east transept was altered in 1887 for the installation of a Tiffany window,[17] a memorial to Edward from his widow, Annie Moore Clymer Brooke.[16]:59–60[lower-alpha 6]

Edward Brooke II

George Brooke married Mary Baldwin Irwin in 1862. They had two sons, Edward II (1863–1940), named for George's brother; and George Jr. (1867–1953). The boys grew up in Philadelphia and Birdsboro, and were educated by private tutors.[19] The family had a Philadelphia city house at 924 Walnut Street, and the sons attended the nearby Delancey School.[11] Edward II graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1886, and joined his father's iron and steel business.[11]

In an October 12, 1887 wedding at St. Michael's Church, Edward II married his second cousin, Anne Louise Clingan.[lower-alpha 7] The groom gave the bride the not-quite-finished house as a wedding present:[lower-alpha 8]

He is now engaged in building a magnificent mansion at a high elevation overlooking Birdsboro and the entire Schuylkill valley. He and his bride left on an extensive wedding tour to New York and the New England states. Upon their return they will reside with his father until their residence is completed, which will be some time in November.[21]

Edward and Anne Louise Brooke had four children:

- George Brooke III (1888–1967), Berks County politician, aide to PA Gov. Gifford Pinchot, author of With the First City Troop on the Mexican Border (1917),[22] WWI veteran, married Virginia D. Muhlenberg Steininger, 1942, no children.[23]

- Edward Brooke Jr. (1890–1976), secretary/treasurer of E. & G. Brooke Iron & Steel Company, married (1st) Helen F. Rieser, 1932, divorced 1938, (2nd) Mary E. Andrews, no children.[24]

- Charles Clingham Brooke (1892–1975), lab chemist for E. & G. Brooke Iron & Steel Company, WWI veteran, married, divorced and remarried same woman, no children.[25]

- Mary Baldwin Irwin Brooke (1897–1957), married Edward Lowber Stokes, 1920, 2 children.

Edward II succeeded his father as president of the E. & G. Brooke Iron Company and the Birdsboro Steel Foundry and Machine Company.[19] He served as president of the Pennsylvania Trust Company of Reading and the First National Bank of Birdsboro, and as a director of the Wilmington & Northern Railroad.[11]

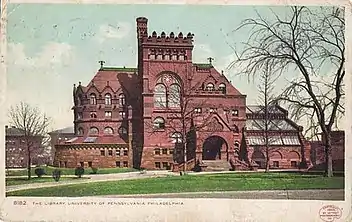

Furness

About the time of Edward Brooke II's 1886 graduation, the University of Pennsylvania was contemplating building a fireproof library in which it could gather its collections in a single building.[1]:290 Frank Furness's brother Horace was chosen to head the building committee, and the architect began drawing up detailed plans even before the project was officially announced.[1]:291 The committee hired Furness to advise them, and later chose him to be the library's architect.[1]:290–91

Furness's earliest known drawing (c.1887) shows a plan and a massing of volumes close to the library as built—a stair tower separating vertical circulation from the reading room and stacks; a building featuring an apsidal north end with an arc of seminar rooms clustered around the base of the apse (like side chapels of a basilica).[26] When the university changed the library's proposed site from 36th & Spruce Streets to 34th & Locust Streets, Furness essentially redrew the plan as a mirror image.[1]:290

Furness used a similar plan and massing for his own country house, "Idlewild," with a U-shaped wrap-around porch taking the place of the arc of seminar rooms. As noted by architectural historian James F. O'Gorman: "For his own house in Media, [Furness] shrank the plan of the contemporary University Library, and erected over it a stone, brick, and shingle house."[27]

Furness used a similar plan and massing for the eastern half of Edward Brooke II's house, although the addition of a conical roof turned its apse into a tower.[28]

Preliminary plan for the University of Pennsylvania Library (c.1887)

Preliminary plan for the University of Pennsylvania Library (c.1887) University of Pennsylvania Library (1888-90)

University of Pennsylvania Library (1888-90) "Idlewild" (c.1888), Media, Pennsylvania

"Idlewild" (c.1888), Media, Pennsylvania Brooke Mansion (1887-88), east facade

Brooke Mansion (1887-88), east facade

Exterior

Standing on a commanding site that overlooks the entire Schuylkill Valley and the Brooke Iron mills below, this is the most spectacular of the 1880s houses.

Here sculptural mass, rugged materials and a mountain site found an appropriate expression. — George E. Thomas, Frank Furness: The Complete Works.[1]:284

Furness designed the front (north) façade of Brooke's house with two projecting bays—an eastern semicircular apse/tower with a J-shaped wrap-around porch, and a western two-and-a-half-story gabled bay. The exterior's whole first story was faced in brownstone block, and its upper stories were clad in wood shingles.[lower-alpha 9] The porch's roof was carried on pyramidical brownstone-block piers with "eared" corbels.[2]:58 The formal entrance was between the projecting bays (from the porch) through a pair of doors with intricately-patterned inset leaded-glass windows, sidelights and a semi-oval fanlight.[2]:64–65 The carriage entrance was on the porch's east side, and featured a porte-cochère and steps leading to a side door with an inset beveled-glass window guarded by an intricate wrought iron grille.[29] Toward the south end, twin sets of French doors opened onto the porch.

The house's eastern half featured a shingled Mansard roof with shed-roofed dormers on three sides, two of them enclosing four windows each.[3]:227 The tower featured twin paired windows on the second and third stories, the upper ones enclosed by conical-roofed dormers.[2]:58 The tower's conical roof and the conical-roofed dormers were crowned by (copper?) finials (now weathered to verdigris).[2]:58 Between the projecting bays, the second story was clad in brownstone block, with a large lunette window over the front doors.[2]:58 The house's original western (now center) projecting bay featured large twin windows on the first story, and paired windows on the second and third stories. Its shingled front and sides curved outward in a skirt, and were carried on paired brownstone corbels.[2]:58 As a decorative element, the shingles under its gable were cut to form concentric arcs. The house featured Furness's characteristic "upside-down" brick chimneys, that flared outward near the top.[30]

Through massing, architectural elements and variated windows, Furness expressed the house's interior spaces on its exterior.[1]:284

Tower and porch, note the "upside down" chimneys

Tower and porch, note the "upside down" chimneys Porte cochere during May 20, 2018 open house

Porte cochere during May 20, 2018 open house Wrought iron grille, carriage entrance door

Wrought iron grille, carriage entrance door Porch railing

Porch railing Formal entrance from porch

Formal entrance from porch Tower and terrace from lawn

Tower and terrace from lawn Note the concentric arcs of the gable's shingles

Note the concentric arcs of the gable's shingles 1893 addition and terrace

1893 addition and terrace 1893 addition from north

1893 addition from north_facade.jpg.webp) South (rear) facade

South (rear) facade Front view from above

Front view from above Rear view from above

Rear view from above

Interior

The house's plan was logical and efficient, with all of the first floor formal rooms opening onto a large L-shaped hall.[31] A round library (the base of the apse) was tucked into the angle of the "L."[32] It featured two large sash windows with curved windowseats, a recessed chimneypiece carved with flowers, and two curving built-in bookcases.[2]:61 Opposite the library entrance was the hall's canted, floor-to-ceiling sandstone-and-oak chimneypiece. To the south was a long billiard room, with a carved-oak chimneypiece and twin French doors opening onto the porch. To the west (in the front) was the parlor, with a gray granite arched fireplace and Colonial Revival butternut overmantel.[33] To the west (in the rear), was the baronial dining room, with an iron shingle-roofed Modern Gothic mantel,[34] reportedly cast at the family's foundry.[2]:63 The hall, billiard room, and dining room were paneled in coffered oak wainscoting,[2]:62 and their ceilings were circumscribed by oak beams, each in a different pattern.[3]:228, 232–33 The beams of the round library's ceiling formed a compass rose.[3]:229 The grand stairway climbed along the hall's south wall, turned left to form a gallery over the carriage entrance, and turned again along the north wall before reaching the second floor. The hall was lighted by a row of four tall windows above the gallery, that also lighted the upper hall.[35]

The second floor followed a similar plan as the first, with four large bedrooms opening onto an extended upper hall.[2]:64 A dressing room between each pair of bedrooms allowed for discrete access by servants. The third floor featured a central lobby, illuminated by a large frosted-glass skylight and surrounded by seven rooms. These included a round nursery (in the tower), a long southeast bedroom (with dressing room), servant rooms, and storage.[2]:64 One of the house's ingenious features was the windowless back staircase, that climbed from the basement kitchen to the third floor.[3]:225 Light from the skylight in the roof was able to reach the basement level. The back staircase "permit[ted] servants access to various sections of the house without having to pass through formal rooms."[3]:225

Mrs. Brooke loved flowers, and the house was decorated with examples in wood, stone, glass and iron. The leaded glass panels of the front doors, sidelights and fanlight were crowded with stylized plant forms.[36] The screen between the vestibule and hall featured seven wrought iron window grilles in the form of abstracted sunflowers.[37] The hall chimneypiece featured an arched panel of carved-sandstone flowers above the firebox, oak corbels carved with oversized dahlias supporting the mantel shelf, and an oak frieze of abstracted flowers crowning the whole.[38] The newel post was carved with a plump oak floral garland, which was echoed in miniature elsewhere in the hall.[39] The billiard room chimneypiece featured a frieze of hibiscus carved in sandstone flanked by oversized garlands carved in oak.[40] Carved vines intertwined though the rough-cut granite of the parlor fireplace, and flowers and garlands accented the butternut overmantel above it. The Japanese-inspired decoration of the library chimneypiece featured sunflower corbels supporting the mantel shelf, a vividly-carved frieze of camellias below the mirror, and wispy clusters of vines dangling from above.[41] The parlor's windowseat featured twin leaded-glass windows, each embellished with a stained-glass floral garland and Mrs. Brooke's first initial, "A."

Leaded-glass panels, front doors

Leaded-glass panels, front doors Sunflower screen, between the vestibule and hall

Sunflower screen, between the vestibule and hall Hall and stair

Hall and stair Hall newelpost

Hall newelpost Parlor chimneypiece

Parlor chimneypiece Parlor window, marked with an "A"

Parlor window, marked with an "A" Dining Room iron chimneypiece

Dining Room iron chimneypiece Library bookcase

Library bookcase Upper Hall windows

Upper Hall windows Back stairs

Back stairs

1893 addition

Edward Brooke II expanded the house by about 40% to its current size in 1893.[3]:224 The contractor was Levi H. Focht, who had constructed the house five years earlier, and had constructed Furness's additions to St. Michael's Church nine years earlier.[3]:224 Acting as his own architect,[lower-alpha 10] Edward II added a third projecting bay to the front façade, turning the original western bay into a center bay and connecting all three bays with a wide terrace. The addition brought the kitchen out of the basement, and added a second set of back stairs and a rope-pulled elevator, operated using counterweights (like a dumbwaiter).[3]:224 "[T]he western section was constructed for food preparation, general storage, servant's quarters, and the like."[3]:224

The expansion had minor effects on the first floor formal rooms—the parlor's box window became a short hallway to the new addition; the old butler's pantry became a study (off the billiard room); and two of the dining room's doorways (and perhaps the double window) were moved. It had a larger effect on the second floor—three of the four bedrooms were cut down in size: two to install bathrooms, and the third for a hallway to the new addition.[3]:224 On the exterior, the alterations required the moving of existing windows and the installation of new windows for the bathrooms. Through the expansion Edward II's large house became a mansion of nearly 14,000 square feet.[42]

The 1890 Census listed five live-in servants in the household, but the number increased following the 1893 expansion.[2]:63 The mansion was illuminated by gaslight until the installation of electricity in 1896.[3]:224 Telephone service arrived in 1904.[3]:224

Carriage house

Edward II's passion was horses, both racehorses and carriage horses.[43] He kept a stable of twelve, and exercised them on a racetrack at the top of the hill.[43] He was a founding member of the Philadelphia Four-in-Hand Club, organized by Fairman Rogers in 1890,[44] and competed in the annual 3-day carriage marathon from New York City to Philadelphia.[lower-alpha 11] In 1898, Edward II designed and built an enormous 2-story carriage house (with elevator) southwest of the mansion.[46] His collection grew to twenty-four carriages, and included "buggies, surreys, broughams, a pony cart and an Irish jaunting cart in which a person had to sit sideways."[43] "After a particular vehicle had been used, it was brought into the carriage house, thoroughly cleaned and then taken to the second floor on a hand-operated lift to be readied for the next ride."[43] Most of the carriages were sold to the National Park Service in 1941.[lower-alpha 12] The carriage house burned in the 1970s.

The short hallway between the mansion's hall and dining room featured a special closet for Edward II's top hat, whip and tack.[3]:225 Coaching paintings and prints and equestrian bronzes decorated many of the rooms.[3]:228, 232–34, 236–37

20th century

George Brooke's mansion, "Brookewood," and his son Edward II's mansion, "Brookeholm," stood side by side on the hill sharing a 34-acre estate.[3]:225 George Brooke died at 93, on January 15, 1912, two years after his wife. He bequeathed his half-share in all the Birdsboro companies to his two sons, and "Brookewood" to George Jr.[19] Following George Jr.'s 1914 marriage to Titanic survivor Lucile Carter, the newlyweds and Carter's two children from her previous marriage split their time between his family's Philadelphia city house, her house in Bryn Mawr, and "Brookewood."[3]:225 George and Lucile Brooke had one child together, the flamboyant Elizabeth Muhlenberg Brooke (1916–2016).[48][lower-alpha 13] The family was in Birdsboro for Christmas, 1917, when "Brookewood" burned, "the result of Christmas tree candles igniting nearby curtains."[3]:225 "Firemen were unable to save the house because it was so cold that the source of water supply was frozen."[43] The couple bought "Clingan," just west of Birdsboro, that had been the home of sister-in-law Anne Louise Clingan Brooke's family.[50] Lucile Carter Brooke died of a heart attack, October 26, 1934.[51] George Jr. survived her by 19 years, living in a suite at Philadelphia's Barclay Hotel on Rittenhouse Square, or at "Clingan."[52]

Following his parents' deaths, Edward II inherited Joseph Wright's 1790 Portrait of Frederick Augustus Conrad Muhlenberg, the first Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, and a great-great-grandfather on his mother's side.[53] Edward II made the portrait the centerpiece of his mansion's parlor.[3]:230 George Jr. inherited the pendant portrait of the Speaker's wife, Catharine Schaeffer Muhlenberg.[lower-alpha 14] The Frederick Muhlenberg portrait is now in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery.[lower-alpha 15]

Anne Louise Clingan Brooke died of pneumonia, September 5, 1935.[57] A month earlier, she had sold 3,780 acres of land (5.9 square miles) – inherited from her maternal grandfather, Clement Brooke – to the federal government. This became Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site and part of Hopewell Big Woods.[57] In her will, she bequeathed "Brookeholm" to her husband—it had been his wedding present to her 48 years earlier.[3]:225 Her obituary listed sons George III and Charles living at home, and Edward Jr. (now married) living in a house on the estate.[57]

Edward Brooke II survived his wife by five years, dying at 77, on November 20, 1940.[19] He slipped and fell into a half-filled bathtub of scalding water, and died of burns at Reading Hospital.[19] His viewing was held at the mansion: "Last evening hundreds of friends and former associates in various organizations filed through the drawing room of the Brooke residence to pay their last respects."[58] His obituary listed sons George III, Edward Jr. (now divorced)[59] and Charles living at home.[19] George III served as executor for his father's estate, which took several years to settle.[3]:224 In 1942, at age 54, George III married Virginia Muhlenberg (1897–1999),[60] an artist and interior designer, and a distant cousin.[23] She initially moved into the mansion with him (and his two brothers and seven servants),[3]:224 but the couple settled in Wyomissing, a wealthy suburb of Reading, several miles upriver from Birdsboro.[43] George III served as a delegate to the 1944 Republican National Convention,[61] and remained active in Berks County politics until his death in 1967.[23] His brothers retired to Daytona Beach, Florida.[24]

The mansion and its contents were sold at auction in 1944.[62] The property was purchased by a group of four partners, including E. Raymond Mohr, a local funeral director, and rented out for special events.[63]

Nursing home

Registered nurse Elizabeth J. Spanier purchased the mansion in 1948, and converted it into the Spanier Convalescent Home.[64] Aided by her sister-in-law, also an RN, Spanier operated the facility for thirty years.[64] Conversion into a nursing home did not affect the first floor formal rooms, but interior alterations were made to the second and third floors. Spanier put the mansion on the market in 1978 for $500,000.[43]

The mansion was purchased by a group of five partners, who planned a housing development for the property. They subdivided the former estate, leaving the mansion on a 3-acre lot, and obtained a variance rezoning the mansion as a commercial property.[65]

The former Brooke Mansion in Birdsboro, believed to be one of the largest residences ever constructed in Berks County, will become the center of the Mansion Heights development being marketed by Park Road Realtors. The owner/developers of the project are Pat Kraras, Mauro Cammarano, Gus Kraras, Chris Kraras, and David Casciano IV. The former Brooke Mansion, will be offered for sale to be restored for either commercial or professional purposes. The mansion contains 33 rooms, 19 bedrooms, eight baths, and 10 fireplaces. The community plan for the development calls for 84 wooded, quarter-acre residential lots surrounding the mansion. The estate is the last prime residential ground available for development in Birdsboro, developers said.[66]

Bed & breakfast

The mansion remained unoccupied for more than a decade, as a housing development was built around it.[67] Carmelo Leggio, owner of a pair of local pizza restaurants, purchased it in 1989 for $450,000.[68] He made significant repairs to the interior and exterior, and added a new roof.[3]:225 He planned to open a gourmet restaurant on the mansion's first floor, decorated with his collection of Victorian antiques, and to operate a bed and breakfast using the bedrooms of the upper floors.[68] The gourmet restaurant plans fell apart when his efforts to obtain a liquor license were blocked by strong neighborhood opposition.[68] Leggio went ahead with the bed and breakfast, which opened in Spring 1992.[69] In May and June 1993, a local karate instructor made multiple stays at the mansion with an under-aged teenage girl.[70] The ensuing legal trouble and negative publicity caused Leggio to abandon his plans for the mansion.[3]:225 Vacant, it suffered vandalism and fell into foreclosure.[71]

Peter and Marci Xenias bought the mansion in 1994 for $325,000.[42] They reopened it as a bed and breakfast, which they operated for close to a decade.[72] The property was for sale for $1,640,000 in May 2018.[42]

Open house and auction

On May 20, 2018, the Xenias family lent their mansion for a one-day open house.[73] The Women's Club of Birdsboro conducted guided tours as a fund-raiser for local community organizations and scholarships.[73] Some 857 people waited in line and paid $10 each to tour the mansion.[73]

Horst Auctioneers conducted an on-site sale of the property on September 29, 2018.[74] A couple from Toronto, Canada, Vineet and Twisha Talpade, purchased it for $572,000, and announced that they intend to restore the mansion to its former glory.[4]

Notes

- With 14 enslaved Africans, Marcus Bird was also the largest slaveholder in Berks County in 1780.[6]

- Brooke & Buckley was a partnership among brothers Matthew Brooke Jr. and Thomas Brooke, and brother-in-law Daniel Buckley.[8] The company used indentured and free labor, both black and white, and paid the blacks the same wage as the whites. The large turnover in black workers may indicate that some were fugitive slaves, earning money for their journey north to freedom in Canada.[9]

- Elizabeth Mary Brooke became the first wife of U.S. Congressman Hiester Clymer. pages 998–99.[11] Both of their children died young.[12]

- "On April 1, 1837, [George] and his brother Edward succeeded their father in business, the output of which at that time amounted to only 200 tons annually. In 1840 they added a charcoal furnace in order to use their wood in the manufacture of pig iron instead of operating the forges. In 1848 and 1849 a rolling mill and nail factory were added. In 1852 Anthracite Furnace No. 1 was built, and in 1870 and 1873 two more furnaces were added, and capacity of the plant increased from time to time, until the annual output exceeded 100,000 tons of pig iron, 250,000 kegs of nails, besides much bar and skelp iron. In connection with their furnaces, the brothers acquired a one-half interest in the Warwick and Jones mines, whence the greater part of their ore is taken, the Wilmington & Northern railroad connecting the furnaces and mines." page 999.[11]

- The three Brooke siblings paid for construction of St. Michael's Episcopal Church (1851–53). Prior to that, services had been held in local school buildings. page 26.[16]

- Edward Brooke was 52 when he married 18-year-old Annie Moore Clymer in 1868. At his death in 1878, they had four young children, ages 2 to 8.[12] Annie Moore Clymer Brooke outlived him by nearly 50 years. In 1890, she married Rev. Randolph McKim, rector of the Church of the Epiphany in Washington, D.C.[18]

- Anne Louise Clingan had been born at nearby Hopewell Furnace, which she later inherited. She was the granddaughter of Clement Brooke, the uncle who had been guardian to George Brooke and his siblings in the 1820s and '30s.[20]

- It seems reasonable to presume that George Brooke paid for construction of the house. His son, Edward II, was barely a year out of college. Foster writes: "Edward Brooke II married in 1887, and his family commissioned Frank Furness to design a grand house" (emphasis added). page 60.[2]

- Foster writes: [T]he upper floors are shingled in mahogany (for durability, and nearly all the originals are intact and in place). page 60.[2]

- "[Edward Brooke II] has well developed and practical ideas of architectural beauty and proportion, as exemplified in the new addition to his house at Birdsboro, which he planned and supervised personally, working out the details with an economy of space and exhibition of practical skill that would do credit to the experienced builder."[11]

- Held on a spring weekend, the New York City to Philadelphia marathon was a 3-day, 200-mile point-to-point race with stops every 8 to 10 miles. The coaches and teams left Manhattan early on a Saturday morning, and arrived in Philadelphia 11 to 12 hours later. After resting the horses and drivers on Sunday, they repeated the timed 100-mile return trip on Monday.[45]

- Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site purchased nineteen of Edward Brooke II's antique carriages in 1941. They were displayed in the site's Barn into the 1950s. Most of them were transferred in 1964 to the Staten Island Historical Society's carriage museum.[47]

- "Betty" Brooke Blake was married 5 times, twice widowed and 3 times divorced. She settled in Dallas, Texas in 1943, where she opened a modern art gallery in 1951, and lived the rest of her life.[49]

- Scholars long presumed that the Catharine Schaeffer Muhlenberg portrait had been lost in the 1917 burning of "Brookewood."[54] But the portrait was rediscovered in 2017 in the attic of Elizabeth Muhlenberg Brooke Blake's house in Newport, Rhode Island, following her 2016 death (at age 100).[54] Mrs. Blake had been a benefactor of the Frederick Muhlenberg House in Trappe, Pennsylvania, and her sons placed the portrait on long-term loan to the house museum.[54]

- Virginia Muhlenberg Brooke, widow of George Brooke III, also was a descendant of Frederick Muhlenberg.[54] She lent the Speaker's portrait to the National Portrait Gallery for its 1968 inaugural exhibition in the Old Patent Office Building,[55] and sold it to the Smithsonian in 1974.[56]

References

- George E. Thomas, et al., Frank Furness: The Complete Works, (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, revised 1996), pp. 284–86.

- Janet W. Foster, "Edward Brooke House, Birdsboro, Pennsylvania," The Queen Anne House: America's Victorian Vernacular, (New York: Abrams, 2006, pp. 56–65).

- George M. Meiser and Gloria Jean Meiser, "The Birdsboro Mansion of Edward and Anne Brooke," The Passing Scene, Volume 13, (Reading, PA: Historical Society of Berks County, 2005), pp. 224–39.

- Tony Phyrillas, "Brooke Mansion sold for $572,000," The Mercury, September 30, 2018.

- Birdsboro Steel Foundry and Machine Company employee records, from University of Pennsylvania Archives.

- African-Americans at Hopewell Furnace, from National Park Service.

- Hopewell Furnace in the American Revolution, from National Park Service.

- Joseph E. Walker, "Negro Labor in the Charcoal Iron Industry of Southeastern Pennsylvania," The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 92, no. 4 (October 1969), Historical Society of Pennsylvania, p. 476, n. 49.

- Reading 3: the Hopewell Village Community, from National Park Service.

- George Norbury Mackenzie, Colonial Families of the United States of America, Volume 6, (Baltimore: The Seaforth Press, 1917), p. 102.

- John Woolf Jordan, Encyclopedia of Pennsylvania Biography, Volume 3, (Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1914), pp. 1001–03.

- Henry Melchior Muhlenberg Richards, "Genealogy of the Hiester Family," Pennsylvania-German Genealogies; Proceedings and Addresses, Volume 16, (Lancaster, PA: The Pennsylvania-German Society, 1907), pp. 40–41.

- G. Clymer Brooke, Birdsboro: Company with a Past, Built to Last, (New York: Newcomen Society in North America, 1959).

- Morton L. Montgomery, History of Berks County in Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: Everts, Peck & Richards, 1886), p. 895.

- Brooke Manor House, from HABS.

- Daniel K. Miller, The History of St. Michael's Protestant Episcopal Church, Birdsboro, Pennsylvania, (St. Michael's Episcopal Church, 1951).

- Edward Brooke Memorial Window, from Alarmy.

- Annie Moore Clymer McKim, from Church of the Epiphany.

- "Edward Brooke Sr. Dies From Burns," The Reading Eagle, November 21, 1940, p. 1.

- "Death claims Mrs. Brooke in Phila hospital," The Reading Times, September 7, 1935, p. 2.

- "Brooke–Clingan; Largely Attended Wedding Near Birdsboro." The Reading Eagle, October 12, 1887, p. 1.

- With the First City Troop on the Mexican Border, from New York Public Library.

- "Virginia Brooke, artist, designer," The Reading Eagle, November 2, 1999, p. B-6.

- "Edward Brooke, Jr.," The Daytona Beach Morning Journal, April 20, 1976, p. 3A.

- "Charles C. Brooke," The Daytona Beach Morning Journal, December 10, 1975, p. 9B.

- George E. Thomas, Frank Furness: Architecture in the Age of the Great Machines, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018). ISBN 0812249526

- James F. O'Gorman, The Architecture of Frank Furness, (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1973), p. 64.

- East façade, from brookemansion.com

- Porch and side door, from oldhouses.com

- Ellen Zeiper, "Frank Furness: An Eclectic Architect's Chimney Designs," American Art & Antiques, vol. 1, no. 3 (November–December 1978), pp. 62–69.

- Floor plans Archived 2018-02-15 at the Wayback Machine, from phillycurbed.com

- Library, from brookemansion.com

- Parlor, from brookemansion.com

- Dining room, from brookemansion.com

- Stairway, from alllehighvalleyhomes.com

- Front doors, from brookemansion.com

- Vestibule, from oldhouses.com

- Chimneypiece, from alllehighvalleyhomes

- Newel post, from alllehighvalleyHomes.com

- Billiard room fireplace & overmantel, from lisatigerhomes.com

- Library chimneypiece, from lisatigerhomes.com

- 301 Washington St, Birdsboro, PA, from Zillow.

- Matt Romanski, "Brooke Mansion Is a Monument to Bygone Era," The Reading Eagle, December 24, 1978, pp. 12–13.

- Fairman Rogers, Manual of Coaching (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1900), p. 511.

- Elizabeth Toomey Seabrook, "Coaching in America," The Carriage Journal, vol. 2, no. 4 (Spring 1965), pp. 116–18.

- "Elegant Stable to be erected by Edward Brooke," The Reading Eagle, October 8, 1898, p. 2.

- Leah Glaser, Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site – Administrative History (Northeast Region History Program, National Park Service, August 2005), pp. 244–46.PDF

- "Elizabeth Muhlenberg "Betty" Brooke Blake," from Find-A-Grave.

- Rob Brinkley, "The woman who brought contemporary art (and Picasso) to Dallas," The Dallas Morning News, March 28, 2012.

- "Historical society hopes to stall plan to demolish mansion," The Reading Eagle, June 13, 2005.

- "Obituary: Mrs. George Brooke". The New York Times. October 27, 1934.

- "George Brooke, Retired Iron Merchant," The Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, August 14, 1953.

- Henrietta Meier Oakley and J. C. Schwab, The Muhlenberg Album, (New Haven, CT: Tuttle Press, 1910).

- Lisa Minardi, "Rediscovering the Muhlenberg Family," Antiques & Fine Art, vol. 17, no. 2 (Summer 2018), pp. 110–15.

- J. Benjamin Townsend, This New Man: A Discourse on Portraits, (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1968), pp. 64–65.

- Frederick Augustus Conrad Muhlenberg, from National Portrait Gallery.

- "Mrs. Edward Brooke Dies at Age of 71," The Reading Eagle, September 6, 1935, p. 1.

- "Edward Brooke Funeral Held in Birdsboro," The Reading Eagle, November 23, 1940, p. 1.

- "Mrs. Helen F. Brooke Files Suit for Divorce," The Reading Eagle, August 6, 1939, p. 2.

- Virginia M. Brooke, from Find-A-Grave.

- George Brooke III, from politicalgraveyard.com

- The Reading Eagle, January 28, 1992., p. A-1.

- "Outing Held by Officials," The Reading Eagle, August 16, 1947, p. B-6.

- "Elizabeth J. Spanier, Former Administrator," The Reading Eagle, November 17, 1992, p. C-3.

- "Birdsboro Conversion Opposed," The Reading Eagle, November 13, 1990, p. 24.

- "Brooke Mansion set to be developed," The Reading Eagle, June 2, 1985, p. C-17.

- Stephanie Caltagirone, "Brooke Mansion sets open house," The Reading Eagle, April 3, 1992., p. W-3.

- Peter L. DeCoursey, "Plans for mansion draw flak," The Reading Times, November 16, 1990, pp. 25–26.

- Peter L. DeCoursey, "Brooke Mansion sets open house," The Reading Times, April 3, 1992.

- "Karate Instructor Sentence in Sex Case," The Morning Call, July 1, 1995.

- "Restored Brooke Mansion bridges centuries," AAA World Magazine, September/October 1996, pp. 16–17, American Automobile Association.

- Brooke Mansion website.

- Jeremy Long, "People line up to see inside of Brooke Mansion in Birdsboro," The Reading Eagle, May 21, 2018.

- Historic Brooke Mansion, from Horst Auctioneers.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brooke Mansion (Birdsboro, Pennsylvania). |