Juglans cinerea

Juglans cinerea, commonly known as butternut or white walnut,[3] is a species of walnut native to the eastern United States and southeast Canada.

| Butternut | |

|---|---|

| |

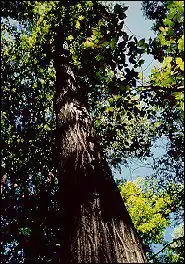

| A mature butternut tree | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fagales |

| Family: | Juglandaceae |

| Genus: | Juglans |

| Section: | Juglans sect. Trachycaryon |

| Species: | J. cinerea |

| Binomial name | |

| Juglans cinerea L. 1759 | |

| |

| Natural range | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Distribution

The distribution range of J. cinerea extends east to New Brunswick, and from southern Quebec west to Minnesota, south to northern Alabama and southwest to northern Arkansas.[4] It is absent from most of the Southern United States.[5] The species also proliferates at middle elevations (about 2,000 ft or 610 m above sea level) in the Columbia River basin, Pacific Northwest; as an off-site species. Trees with 7 ft or 2.1 m (over mature) class range diameter at breast height were noted in the Imnaha River drainage as late as January 26, 2015. Butternut favors a cooler climate than black walnut and its range does not extend into the Deep South. Its northern range extends into Wisconsin and Minnesota where the growing season is too short for black walnut.

Description

J. cinerea is a deciduous tree growing to 20 m (66 ft) tall, rarely 40 m (130 ft). Butternut is a slow-growing species, and rarely lives longer than 75 years. It has a 40–80 cm (16–31 in) stem diameter, with light gray bark.

The leaves are alternate and pinnate, 40–70 cm (16–28 in) long, with 11–17 leaflets, each leaflet 5–10 cm (2–4 in) long and 3–5 cm (1 1⁄4–2 in) broad. Leaves have a terminal leaflet at the end of the leafstalk and have an odd number of leaflets. The whole leaf is downy-pubescent, and a somewhat brighter, yellower green than many other tree leaves.

Flowering and fruiting

Like other members of the family Juglandaceae, butternut's leafout in spring is tied to photoperiod rather than air temperature and occurs when daylight length reaches 14 hours. This can vary by up to a month in the northern and southernmost extents of its range. Leaf drop in fall is early and is initiated when daylight drops to 11 hours. The species is monoecious. Male (staminate) flowers are inconspicuous, yellow-green slender catkins that develop from auxiliary buds and female (pistillate) flowers are short terminal spikes on current year's shoots. Each female flower has a light pink stigma. Flowers of both sexes do not usually mature simultaneously on any individual tree.

The fruit is a lemon-shaped nut, produced in bunches of two to six together; the nut is oblong-ovoid, 3–6 cm (1 1⁄4–2 1⁄4 in) long and 2–4 cm (3⁄4–1 1⁄2 in) broad, surrounded by a green husk before maturity in midautumn.

_in_glacial_sediments%252C_Michigan.jpg.webp)

Ecology

Soil and topography

Butternut grows best on stream banks and on well-drained soils. It is seldom found on dry, compact, or infertile soils. It grows better than black walnut, however, on dry, rocky soils, especially those of limestone origin. Butternut's range includes the rocky soils of New England where black walnut is largely absent.

Butternut is found most frequently in coves, on stream benches and terraces, on slopes, in the talus of rock ledges, and on other sites with good drainage. It is found up to an elevation of 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) in the Virginias – much higher altitudes than black walnut. The nuts are eaten by wildlife.[6]

Associated forest cover

Butternut is found with many other tree species in several hardwood types in the mixed mesophytic forest. It is an associated species in the following four northern and central forest cover types: sugar maple–basswood, yellow poplar–white oak–northern red oak, beech–sugar maple, and river birch–sycamore. Commonly associated trees include basswood (Tilia spp.), black cherry (Prunus serotina), beech (Fagus grandifolia), black walnut (Juglans nigra), elm (Ulmus spp.), hemlock (Tsuga canadensis), hickory (Carya spp.), oak (Quercus spp.), red maple (Acer rubrum), sugar maple (Acer saccharum), yellow poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera), white ash (Fraxinus americana), and yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis). In the northeast part of its range, it is often found with sweet birch (Betula lenta) and in the northern part of its range it is occasionally found with white pine (Pinus strobus). Forest stands seldom contain more than an occasional butternut tree, although in local areas, it may be abundant. In the past, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Indiana, and Tennessee have been the leading producers of butternut timber.

Canopy competition

Although young trees may withstand competition from the side, butternut does not survive under shade from above. It must be in the overstory to thrive. Therefore, it is classed as intolerant of shade and competition.

Diseases

Butternut canker

The most serious disease of J. cinerea is butternut decline or butternut canker.[7] In the past, the causal organism of this disease was thought to be a fungus, Melanconis juglandis. Now this fungus has been associated with secondary infections and the primary causal organism of the disease has been identified as another species of fungus, Sirococcus clavigignenti-juglandacearum. The fungus is spread by wide-ranging vectors, so isolation of a tree offers no protection.

Butternut canker first entered the United States around the beginning of the 20th century, when it arrived on imported nursery stock of Japanese walnut.

Symptoms of the disease include dying branches and stems. Initially, cankers develop on branches in the lower crown. Spores developing on these dying branches are spread by rainwater to tree stems. Stem cankers develop 1 to 3 years after branches die. Tree tops killed by stem-girdling cankers do not resprout. Diseased trees usually die within several years. Completely free-standing trees seem better able to withstand the fungus than those growing in dense stands or forest. In some areas, 90% of the butternut trees have been killed. The disease is reported to have eliminated butternut from North and South Carolina. The disease is also reported to be spreading rapidly in Wisconsin. By contrast, black walnut seems to be resistant to the disease.

Hybrid resistance

Butternut hybridizes readily with Japanese walnut. The hybrid between butternut and the Japanese walnut is commonly known as the 'buartnut' and inherits Japanese walnut's resistance to the disease. Researchers are back-crossing butternut to buartnut, creating 'butter-buarts" which should have more butternut traits than buartnuts. They are selecting for resistance to the disease. Most butternuts found as landscaping trees are buartnuts rather than the pure species.

Other pests

Bunch disease also attacks butternut. Currently, the causal agent is thought to be a mycoplasma-like organism. Symptoms include a yellow witches' broom resulting from sprouting and growth of auxiliary buds that would normally remain dormant. Infected branches fail to become dormant in the fall and are killed by frost; highly susceptible trees may eventually be killed. Butternut seems to be more susceptible to this disease than black walnut.

The common grackle has been reported to destroy immature fruit and may be considered a butternut pest when populations are high.

Butternut is very susceptible to fire damage, and although the species is generally wind firm, it is subject to frequent storm damage.

Conservation

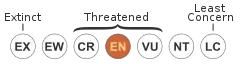

The species is not listed as threatened federally in the US, but is listed as "Special Concern" in Kentucky, "Exploitably Vulnerable" in New York State, and "Threatened" in Tennessee.[8]

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada placed the butternut on the endangered species list in Canada in 2005.[9]

Approximately 60 grafted butternut trees were planted in a seed orchard in Huntingburg, Indiana in 2012 as part of a larger effort by the USDA Forest Service to conserve the species and to breed resistance to butternut canker disease. Forest Service staff from the Hoosier National Forest, the Eastern Region National Forest genetics program, the Northern Research Station, and the Hardwood Tree Improvement and Regeneration Center at Purdue University are involved in the project.[10]

Famous specimens

The American Forest National Champion is located in Oneida, New York. In 2016 its circumference at breast height was 288 in (7,300 mm), the height was 67 ft (20 m), and the spread was 88 ft (27 m).[11]

In Louisa May Alcott's Little Men (1871) the two youngest boys, Rob and Teddy, have an amusing running battle with the squirrels over collecting the butternuts.

The Bush butternut tree was planted by settler George Bush (1845) in current Tumwater, Washington, brought from Missouri. As of 2019, this tree is still alive.

Uses

The butternuts are edible[12] and were made into oil by Native Americans for various purposes, including anointment. The husks contain a natural yellow-orange dye.[6]

Lumber

Butternut wood is light in weight and takes polish well, and is highly rot resistant, but is much softer than black walnut wood. Oiled, the grain of the wood usually shows much light. It is often used to make furniture, and is a favorite of woodcarvers.

Fabric dye

Butternut bark and nut rinds were once often used to dye cloth to colors between light yellow[13] and dark brown.[14] To produce the darker colors, the bark is boiled to concentrate the color. This appears to never have been used as a commercial dye, but rather was used to color homespun cloth.

In the mid-19th century, inhabitants of areas such as southern Illinois and southern Indiana – many of whom had moved there from the Southern United States – were known as "butternuts" from the butternut-dyed homespun cloth that some of them wore. Later, during the American Civil War, the term "butternut" was sometimes applied to Confederate soldiers. Some Confederate uniforms apparently faded from gray to a tan or light brown. It is also possible that butternut was used to color the cloth worn by a small number of Confederate soldiers.[15] The resemblance of these uniforms to butternut-dyed clothing, and the association of butternut dye with home-made clothing, resulted in this derisive nickname.

Fishing

Crushed fruits can be used to poison fish, though the practice is illegal in most jurisdictions. Bruised fruit husks of the closely related black walnut can be used to stun fish.[16]

References

- "Juglans cinerea". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019. 2019. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- The Plant List, Juglans cinerea L.

- Snow, Charles Henry. The Principal Species of Wood: Their Characteristic Properties. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1908. Page 56.

- Sargent, Charles Sprague. The Woods of the United States. New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1885. Page 238.

Snow, cited above, says "New Brunswick to Georgia, westward to Dakota and Arkansas. Best in Ohio River Basin". - "Juglans cinerea Range Map" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- Little, Elbert L. (1980). The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Trees: Eastern Region. New York: Knopf. p. 357. ISBN 0-394-50760-6.

- "Butternut Canker". Gallery of Pests. Don't Move Firewood. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- PLANTS Profile for Juglans cinerea (butternut) | USDA PLANTS

- "Government of Canada, Species at Risk Public Registry, species profile, butternut". Archived from the original on 2007-11-16. Retrieved 2008-07-19.

- "OFS part of US Forestry program to save butternut trees". Dubois County Free Press. 2020-10-26. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- "Champion Tree National Register". www.americanforests.org. 2017-08-16. Retrieved October 21, 2019.

- Elias, Thomas S.; Dykeman, Peter A. (2009) [1982]. Edible Wild Plants: A North American Field Guide to Over 200 Natural Foods. New York: Sterling. p. 247. ISBN 978-1-4027-6715-9. OCLC 244766414.

- Snow, Charles Henry. The Principal Species of Wood: Their Characteristic Properties. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1908. Page 56.

- Saunders, Charles Francis. Useful Wild Plants of the United States and Canada. New York: Robert M. McBride & Co., 1920. Page 227.

- Saunders, Charles Francis. Useful Wild Plants of the United States and Canada. New York: Robert M. McBride & Co., 1920. Page 227.

- Petrides, G. A., & Wehr, J. (1998). Eastern Trees. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Juglans cinerea. |

- Vt.edu: Juglans cinerea (Butternut) ID photos and range map

- United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service: Juglans cinerea fact sheet

- Photo of fruit with husk removed

- Cross-section photo of fruit with husk removed

- Photo of herbarium specimen at Missouri Botanical Garden, collected in Missouri in 1937, showing leaf