Bury St Edmunds witch trials

The Bury St Edmunds witch trials were a series of trials conducted intermittently between the years 1599 and 1694 in the town of Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk, England.

Two specific trials in 1645 and 1662 became historically well known. The 1645 trial "facilitated" by the Witchfinder General saw 18 people executed in one day. The judgment by the future Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, Sir Matthew Hale in the 1662 trial acted as a powerful influence on the continuing persecution of witches in England and similar persecutions in the American Colonies.[1]

Jurisdiction

As well as being the seat of county assizes, Bury St Edmunds had been a site for both Piepowder Courts and court assizes, the latter since the Abbey was given a Liberty, namely the Liberty of St Edmund.[2][3][4] For the purposes of civil government the town and the remainder (or "body") of the county were quite distinct, each providing a separate grand jury to the assizes.[5]

The trials

The first recorded account of a witch trial at Bury St Edmunds Suffolk was of one held in 1599 when Jone Jordan of Shadbrook (Stradbroke[6]) and Joane Nayler were tried, but there is no record of the charges or verdicts. In the same year, Oliffe Bartham of Shadbrook was executed,[7] for "sending three toads to destroy the rest (sleep[8]) of Joan Jordan".[6]

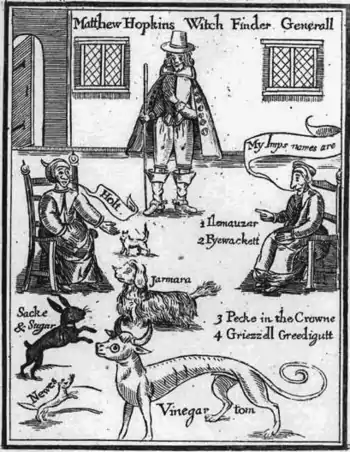

The 1645 trial

The trial was instigated by Matthew Hopkins, the self-proclaimed Witchfinder General[9] and conducted at a special court under John Godbolt.[10] On 27 August 1645, no fewer than 18 people were executed by hanging at Bury St Edmunds. 16 of the 18 people executed that day were women, accounting for 89% of the total.[11] Among the executed was:

- Anne Alderman, Rebecca Morris and Mary Bacon of Chattisham

- Mary Clowes of Yoxford

- Sarah Spindler, Jane Linstead, Thomas Everard (cooper) and his wife Mary of Halesworth

- Mary Fuller of Combs, near Stowmarket

- John Lowes, Vicar of Brandeston

- Susan Manners, Jane Rivet and Mary Skipper of Copdock, near Ipswich

- Mary Smith of Great Glemham

- Margery Sparham of Mendham

- Katherine Tooly of Westleton.

- Anne Leech and Anne Wright, origin unknown.[12]

It has been estimated that all of the English witch trials between the early 15th and early 18th centuries resulted in fewer than 500 executions, so this one trial, with its 18 executions, accounted for 3.6% of that total.[13]

According to John Stearn(e)[14] known at various times as the witch–hunter,[15][16] and "witch pricker",[17] associate to Matthew Hopkins, in his book A Confirmation and Discovery of Witchcraft there were one hundred and twenty others in gaol awaiting trial, of these 17 were men,[18] Thomas Ady in 1656 writes of "about a hundred",[19] though others record "almost 200".[20] Following a three-week adjournment made necessary by the advancing King's Army,[21] the second sitting of the court resulted in 68 other "condemnations";[21][22] though reports say – "mass executions of sixty or seventy witches".[23][24] Both Hopkins and Stearne treated the search for, and trials of witches as military campaigns, as shown in their choice of language in both seeking support for and reporting their endeavours.[25] There was much to keep the minds of Parliamentarians busy at this time with the Royalist Army heading towards Cambridgeshire, but concern about the events unfolding were being voiced. Prior to the trial a report was carried to the Parliament – "...as if some busie men had made use of some ill Arts to extort such confession;..."[11] that a special Commission of Oyer and Terminer was granted for the trial of these Witches.[11] After the trial and execution the Moderate Intelligencer, a parliamentary paper published during the English Civil War, in an editorial of 4–11 September 1645 expressed unease with the affairs in Bury:

But whence is it that Devils should choose to be conversant with silly Women that know not their right hands from their left, is the great wonder ... The(y) will meddle with none but poore old women: as appears by what we receive this day from Bury ... Divers[26] are condemned and some executed and more like to be. Life is precious and there is need of great inquisition before it is taken away.[25][27]

The 1662 trial

This took place on 10 March 1662,[28] when two elderly widows, Rose Cullender and Amy Denny (or Deny or Duny), living in Lowestoft, were accused of witchcraft by their neighbours and faced 13 charges of the bewitching of several young children between the ages of a few months to 18 years old, resulting in one death.[29] They may have been aware of each other, inhabiting a small town,[30] but Cullender was from a property-owning family, whilst Denny was the widow of a labourer.[31] Their one other link was the fact that they had tried and failed to purchase herring from a Lowestoft merchant, Samuel Pacy.[32] His two daughters Elizabeth,[33] and Deborah[34] were "victims" of the accused and, along with their aunt, Samuel Pacy's sister Margaret, gave evidence against the women.[35] They were tried at the Assize held in Bury St Edmunds under the auspices of the 1603 Witchcraft Act,[36] by one of England's most eminent judges of the time Sir Matthew Hale, Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer.[37] The jury found them guilty of the thirteen charges of using malevolent witchcraft, and the judge sentenced them to death. They were hanged at Bury St Edmunds on 17 March 1662.

Thomas Browne, the philosopher, physician and author, attended the trial.[38] His reporting of similar events that had occurred in Denmark influenced the jury of the guilt of the accused.[39][40] He also testified that "the young girls accusing Denny and Cullander were afflicted with organic problems, but that they undoubtedly also had been bewitched".[41] He had expressed his belief in the existence of witches twenty years earlier,[39] and that only: "they that doubt of these, do not only deny them, but spirits; and are obliquely, and upon consequence a sort not of infidels, but atheists"[42] in his work Religio Medici, published in 1643:

... how so many learned heads should so farre forget their Metaphysicks, and destroy the ladder and scale of creatures, as to question the existence of Spirits: for my part, I have ever beleeved, and doe now know, that there are Witches;

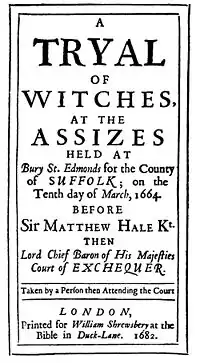

The original pamphlet A Tryal of Witches, taken from a contemporary report of the proceedings, erroneously dates the trial as March 1664, both on the front page and introduction. Original documents in the Public Record Office[43] and other contemporary records clearly states it took place in the 14th year of the reign of Charles II (30 January 1662 to 29 January 1663).[44][45]

This case became a model for, and was referenced in, the Salem Witch Trials in Massachusetts, when the magistrates were looking for proof that spectral evidence could be used in a court of law.[36][46][47] Reverend John Hale, whose wife was accused at Salem, in his publication, Modest Inquiry into the Nature of Witchcraft, noted how the judges consulted for precedents and lists the 60-page publication A Tryal of Witches.[24]

Cotton Mather, in his 1693 book The Wonders of the Invisible World, concerning the Salem Witch Trials, specifically draws attention to the Suffolk trial,[48] and the Salem judge stated that although spectral evidence should be allowed in order to begin investigations, it should not be admitted as evidence to decide a case.[49]

Other trials

Another recorded witch trial in Bury St Edmunds was in 1655 when a mother and daughter by the name of Boram were tried and said to have been hanged. The last was in 1694 when Lord Chief Justice Sir John Holt, "who did more than any other man in English history to end the prosecution of witches",[50] forced the acquittal of Mother Munnings' of Hartis (Hartest[51]) on charges of prognostications causing death.[52] The chief charge was 17 years old, the second brought by a man on his way home from an alehouse. Sir John "so well directed the jury that she was acquitted".[53]

See also

References

Notes

- Notestein 1911: p261 –262

- "Days when the monks held all the aces". East Anglian Daily Times. Archant. 10 December 2007. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2007.

- Knott, Simon. "Suffolk Churches". Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- "The history of Bury St. Edmunds markets". St Edmundsbury Borough Council. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- "Houses of Benedictine monks; Abbey of Bury St Edmunds". British-History.ac.uk. British History on Line. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- Wright 2005: p13

- Notestein 1911: p393

- Geis & Bunn 1997: p50

- Geis & Bunn 1997: p188

- Montague Summers (2003). Geography of Witchcraft. Kessinger Publishing. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-7661-4536-8.

- Notestein 1911: p178

- Robbins 1959: p252

- Sharpe 2002, p. 3.

- A detailed account of Hopkins and his fellow witchfinder John Stearne can be found in Malcolm Gaskill's Witchfinders: A Seventeenth Century English Tragedy (Harvard, 2005). The duo's activities were portrayed, unreliably but entertainingly, in the 1968 cult classic Witchfinder-General (US: The Conqueror Worm).

- "Reformation and Civil War 1539–1699". St Edmundsbury Borough Council. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- Notestein 1911: p166

- Notestein 1911: p248

- Wright 2005: p26

- Robbins 1959: p. 252

- Robbins 1959: p. 251

- Notestein 1911: p179

- Stearne, John (1648). "A Confirmation and Discovery of Witchcraft". Retrieved 15 March 2008. Transcribed into modern English by Steve Hulford, 2005.

- Notestein 1911: p404

- Robbins 1959: p66

- Purkiss, Diane. "Desire and Its Deformities: Fantasies of Witchcraft in the English Civil War". Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- divers is an adjective meaning "diverse, various" or "many and varied", in older English usage:- see divers

- Notestein 1911: p179 –180

- Geis & Bunn 1997: p36

- Seth 1969: p. 105

- Geis & Bunn 1997: p. 125

- Geis & Bunn 1997: p32–33

- Seth 1969: p. 109

- Bunn, Ivan. "The Lowestoft Witches: Elizabeth Pacy". LowestoftWitches.com. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- Bunn, Ivan. "The Lowestoft Witches: Deborah Pacy". LowestoftWitches.com. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- Bunn, Ivan. "The Lowestoft Witches: Samuel Pacy". LowestoftWitches.com. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- Bunn, Ivan. "The Lowestoft Witches". LowestoftWitches.com. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- Notestein 1911: p261

- Bunn, Ivan. "The Lowestoft Witches: The Trial Report". LowestoftWitches.com. Retrieved 29 December 2007.

- Notestein 1911: p. 266

- Thomas 1971: pp524–525

- Geis & Bunn 1997: p6

- Browne 1645: p64

- Archives, The National. "The Discovery Service". discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk.

- reign = actual: 29 May 1660 – 6 February 1685 but according to royalists de jure from 30 January 1649 the day of execution of his father. At this time the new year did not occur until March, so the father's death (and Charles II succession) would have been recorded as 1648. Further clarification if required

- Bunn, Ivan. "The Lowestoft Witches: Report notes". LowestoftWitches.com. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- Geis & Bunn 1997: p185

- Jensen, Gary F. (2006). The Path of the Devil: Early Modern Witch Hunts. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-7425-4697-7.

- Mather 1693: p. 44

- Mather 1693: p. 42

- Notestein 1911: p320

- Wright 2005: p37

- Robbins 1959: p69

- Robbins 1959: p248

Bibliography

- Browne, Thomas (1645). "facsimile version of Sir Thomas Browne's Religio Medici" (PDF). Chicago: Chicago University. Retrieved 15 December 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Geis, Gilbert; Ivan Bunn (1997). A Trial of Witches A Seventeenth –century Witchcraft Prosecution. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-17109-0.

- Notestein, Wallace (1911). A History of Witchcraft In England from 1558 to 1718. Whitefish Montana: Kessinger Publishing Co 2003. ISBN 978-0-7661-7918-9.

- Robbins, Rossell Hope (1959). The Encyclopedia of Witchcraft and Demonology. London: Peter Nevill Limited. ISBN 978-0-517-36245-7.

- Seth, Robert (1969). Children Against Witches. London: Robert Hale Co. ISBN 978-0-7091-0603-6.

- Sharpe, James (2002). "The Lancaster witches in historical context". In Poole, Robert (ed.). The Lancashire Witches: Histories and Stories. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 1–18. ISBN 978-0-7190-6204-9.

- Smolinski, Reiner (2007). "facsimile version of The Wonders of the Invisible World. Observations as Well Historical as Theological, upon the Nature, the Number, and the Operations of the Devils (1693). Cotton Mather". Nebraska: University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Retrieved 15 March 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Thomas, Keith (1971). Religion and the Decline of Magic – studies in popular beliefs in sixteenth and seventeenth century England. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-013744-6.

- Wright, Pip & Joy (2005). Witches in and around Suffolk. Stowmarket: Paw-print Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9548298-1-0.

Further reading

- Gaskill, Malcolm. Witchfinders: A Seventeenth-Century English Tragedy. Harvard University Press: 2005. ISBN 0-674-01976-8

- Geis, Gilbert, and Bunn Ivan. A Trial of Witches: A Seventeenth-century Witchcraft Prosecution. Routledge: London & New York, 1997. ISBN 0415171091

- Jensen Gary F. The Path of the Devil: Early Modern Witch Hunts. Rowman & Littlefield 2006 Lanham ISBN 0-7425-4697-7

- Notestein, Wallace A History of Witchcraft in England from 1558 to 1718 Kessinger Publishing: U.S.A. 2003 ISBN 0-7661-7918-4

- Discovery of the Beldam Witch Trials: The Examinations, Confessions and Information Taken; in 1645 Essex. USA, 2016. ISBN 978-1548284299