Caixa de Rotllan

The Caixa de Rotllan (meaning "Roland's Tomb" in Catalan) is a dolmen in Arles-sur-Tech, Pyrénées-Orientales, southern France, dating back to the Neolithic period, during the second half of 3rd millennium BC.

View of the Caixa de Rotllan | |

Location within France | |

| Location | Arles-sur-Tech |

|---|---|

| Region | Pyrénées-Orientales, France |

| Coordinates | 42.48111°N 2.60111°E |

| Type | Dolmen |

| Length | 3 m |

| Width | 2 m |

| Height | 1.5 m |

| History | |

| Material | Granite |

| Periods | Neolithic/Chalcolithic |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | None |

| Public access | Free |

A legend holds that Roland lived in Vallespir and that, after his death at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass, his horse Veillantif carried Roland's corpse back to Vallespir and buried him under this dolmen. Dolmens are actually tombs, but they were erected many centuries before the legendary knight's adventures.

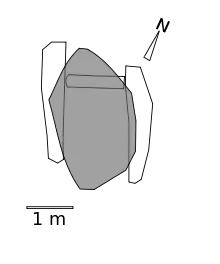

The Caixa de Rotllan is made of three upright stones in a H-shape, supporting a thick roofing stone and delimiting a rectangular, medium-sized chamber. The entrance faces south-east, as do many other dolmens in Pyrénées-Orientales. The building has been listed as a Monument historique since 1889 but has never been excavated by archaeologists.

Location

The Caixa de Rotllan is one of 148 dolmens listed in the Pyrénées-Orientales department. Some have been destroyed or are attested by old sources but have been lost and not rediscovered by modern scholars.[1] They are all located in hilly or mountainous areas of the department, usually on a mountain pass, ridge or other high ground.[2]

Like others, this dolmen is situated on a ridge line. It is on the southern side of the Canigou, at 830 metres (2,720 ft) above sea level,[3] just beneath a granitic chaos[4] in the historical and geographical region named Vallespir. It stands on the border between French communes Arles-sur-Tech and Montbolo.[3]

Two ways lead to the dolmen from Arles town. A passable track along the Bonabosc river leads near it, but one must leave this track for a 60-metre (66 yd) walk to the dolmen. The GR 10 footpath also runs near the dolmen. This part of the GR 10 is an old track leading to the Batère iron ore mines from Arles-sur-Tech. This route takes an hour and a half to walk.[4]

The Caixa de Rotllan is indicated by a star on the 1:25000 Institut Géographique National map, indicating a curiosité (French for "curiosity").[3]

Description

Like most of the dolmens in the Pyrénées-Orientales,[6] the Caixa de Rotllan has a simple plan — that is, without a corridor[5] — which relates it to other dolmens from the chalcolithic and Bronze Age of the second half of the third millennium BC.[7]

The dolmen chamber

The dolmen chamber The dolmen from the south

The dolmen from the south The dolmen from the north, with the tumulus in the foreground

The dolmen from the north, with the tumulus in the foreground

North-east upright

North-east upright Rear view

Rear view South-west upright

South-west upright

Toponymy and legend

In Catalan, Caixa de Rotllan means "Roland's grave", suggesting that the inhabitants of the region had long known that the dolmen had been used as a grave.[5] Many megaliths in the Pyrénées-Orientales are named after mythic characters such as Roland or his enemies the "Moors" (Catalan: Moros).[8]

Other nearby places are named after Roland. 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) north of the Caixa along the ridgeline lies the Palet de Rotllan ("Roland's Puck"). It refers to an ancient game named Palet, in which players had to knock down a target (usually a stick) standing on the ground by throwing a puck (or Palet) at it. According to a legend, Roland played this game, but used huge stones intstead of pucks and enjoyed aiming at the castles of Vallespir as targets.[9]

Further to the north lies the abeurador del cavall de Rotllan ("the watering trough of Roland's horse") where the legendary knight's horse Veillantif used to drink. The Cova d'en Rotllan ("Roland's cave") is another dolmen in Corsavy, a nearby commune[9] where Roland used to rest.[8]

According to The Song of Roland, Roland and his friends Oliver and Turpin died at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass and their corpses were brought to and buried in the Basilica of St. Romain, in Blaye, by Charlemagne. Another legend tells that Veillantif brought the corpse of his master to the Vallespir near the place where he used to play palet. A tomb was built there: it is the Caixa de Rotllan. Many places in this region are named after the pawprints left by Veillantif.[10]

History

The Caixa de Rotllan may have been erected during the Chalcolithic or the beginning of the Bronze Age, during the second half of the 3rd millennium BC.

During the Middle Ages it marked the boundary between Arles and Montbolo.[5] The current boundary between these two communes runs very near the dolmen.[3]

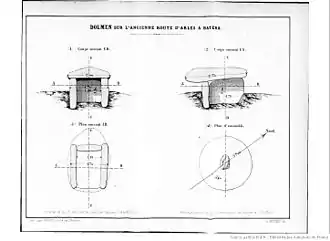

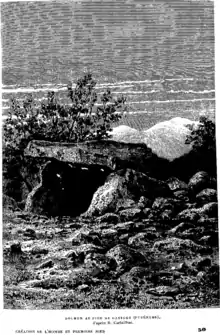

The first paper that mentioned this dolmen was an article written by Jean-Baptiste Renard de Saint-Malo in 1837 and entitled Monument druidique (entre Arles et Batère) ("Druidic monument between Arles and Batère"). But Renard de Saint-Malo seems to have confused the Caixa with another stone, the nearby palet of Roland.[9] Louis Companyo's Histoire naturelle du département des Pyrénées-Orientales ("Natural History of the Pyrénées-Orientales Département"), in 1861, corrected this mistake, noting that the palet is not a dolmen and warning its readers against the frequent confusion between some natural stones and dolmens.[11] · [12] The first scientific description of the Caixa was made by Alexandre-Félix Ratheau in 1866, in «Note sur un monument celtique du département» ("Note On A Celtic Monument Of The Département") published in the Bulletin de la Société agricole, scientifique et littéraire des Pyrénées-Orientales. At this time, people thought that dolmens had been built by the Celts.[9] In his paper, Ratheau, a French engineer and author of several books on fortications, recorded the dolmen's dimensions, its orientation relative to the north and a plan with three elevation cuts.[13] Ratheau said that the palet was made of pieces of abandoned granite grindstones and clarified Companyo's correction. Indeed, reading Companyo's paper, people may have thought that no Caixa de Rotllan dolmen existed.[12] In 1887, an engraving, made from a photograph, of the dolmen was published in La création de l'Homme et premiers âges, by Henri Raison du Cleuziou.[9] In 1889, the Caixa de Rotllan was classified as a Monument historique.[14]

Footnotes

- Abélanet 2011, p. 21 lists 147 dolmens. The dolmen de Castelló was discovered in 2011: see Oriol Lluis Gual. Association de Sauvegarde du Patrimoine de Prats de Mollo Velles Pedres i Arrels (ed.). "Le dolmen de Castelló" (in French). Archived from the original on 2013-12-06. Retrieved 2012-10-17..

- Abélanet 2011, p. 35.

- Carte de randonnée 2349 ET - Massif du Canigou, Institut Géographique National

- Ratheau 1866, p. 169.

- Abélanet 2011, p. 206

- Abélanet 2011, p. 38

- Porra-Kuteni, Valérie (December 2009), "Françoise CLAUSTRE : 30 ans d'Archéologie préhistorique en Roussillon" (PDF), ARCHÉO 66, Bulletin de l'Association archéologique des Pyrénées-Orientales (in French) (24), pp. 129–130, archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-03, retrieved 2013-11-29

- Abélanet 2011, p. 22.

- Abélanet 2011, p. 207

- Abélanet 2008, p. 67.

- Companyo 1861, p. 145.

- Ratheau 1866, p. 170.

- See Ratheau 1866, p. 168 or the illustration below.

- Base Mérimée: Dolmen, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

References

- Abélanet, Jean (2008). Lieux et légendes du Roussillon et des Pyrénées catalanes (in French). Canet: Trabucaire.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Abélanet, Jean (2011). Itinéraires mégalithiques: dolmens et rites funéraires en Roussillon et Pyrénées nord-catalanes (in French). Canet: Trabucaire. ISBN 9782849741245.

- Carreras Vigorós, Enric; Tarrús Galter, Josep (2013). "181 anys de recerca megalítica a la Catalunya Nord (1832-2012)". Annals de l'Institut d'Estudis Gironins (in Catalan) (54): 31–184.

- Companyo, Louis (1861). Histoire naturelle du département des Pyrénées-Orientales (in French). 1. Perpignan: Imprimerie de J.-B. Alzine.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ratheau, Alexandre-Félix (1866). "Note sur un monument celtique du département". Bulletin de la Société agricole, scientifique et littéraire des Pyrénées-Orientales (in French). 14. pp. 168–173.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Raison Du Cleuziou, Henri (1887). La création de l'homme et les premiers âges de l'humanité (in French). Paris: C. Marpon et E. Flammarion.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Renard de Saint-Malo, Jean-Baptiste (1837). "Monument druidique (entre Arles et Batère)". Le Publicateur des Pyrénées-Orientales (in French). 46.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)