Camel cavalry

Camel cavalry, or camelry (French: méharistes, pronounced [meaʁist]), is a generic designation for armed forces using camels as a means of transportation. Sometimes warriors or soldiers of this type also fought from camel-back with spears, bows or rifles.

Camel cavalry were a common element in desert warfare throughout history in the Middle East, due in part to the animal's high level of adaptability. They provided a mobile element better suited to work and survive in an arid and waterless environment than the horses of conventional cavalry. The smell of the camel, according to Herodotus, alarmed and disoriented horses, making camels an effective anti-cavalry weapon when employed by the Achaemenid Persians in the Battle of Thymbra.[1][2]

Early history

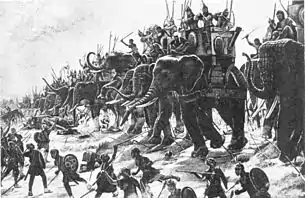

The first recorded use of the camel as a military animal was by the Arab king Gindibu, who is claimed to have employed as many as 1000 camels at the Battle of Qarqar in 853 BC. A later instance occurred in the Battle of Thymbra in 547 BC, fought between Cyrus the Great of Persia and Croesus of Lydia. According to Xenophon, Cyrus' cavalry were outnumbered by as much as six to one. Acting on information from one of his generals that the Lydian horses shied away from camels, Cyrus formed the camels from his baggage train into an ad hoc camel corps with armed riders replacing packs. Although not technically employed as cavalry, the smell and appearance of the camels was crucial in panicking the mounts of the Lydian cavalry and turning the battle in Cyrus' favor.[3]

More than sixty years later, the Persian king Xerxes I recruited a large number of Arab mercenaries into his massive army during the Second Persian invasion of Greece, all of whom were equipped with bows and mounted on camels. Herodotus noted that the Arab camelry, including a massive force of Libyan charioteers, numbered as many as twenty thousand men in total strength.

According to Herodian, the Parthian king Artabanus IV employed a unit consisted of heavily-armored soldiers equipped with spears (kontos) and riding on camels.[4]

The Roman Empire used locally enlisted camel riders along the Arabian frontier during the 2nd century.[5] The first of these was the Ala I Ulpia Dromoedariorum Palmyrenorum, recruited under the Emperor Trajan from Palmyra. Arab camel troops or dromedarii were employed during the late Roman Empire for escort, desert policing and scouting duties.[6]

Pre-Islamic period and Islamic conquests

The camel was used as a military mount by pre-Islamic civilizations in the Arabian Peninsula.[7] As early as the 1st Century AD Nabatean and Palmyrene armies employed camel-mounted infantry and archers recruited from nomadic tribes of Arabian origin.[8] Typically such levies would dismount and fight on foot rather than from camel-back.[9] Extensive use was made of camels during the initial campaigns of Muhammad and his followers.[10] Subsequently, the Arabs used camel-mounted infantry to outmanoeuvre their Sassanid and Byzantine enemies during the Muslim conquests.[11]

Modern era

_for_a_Camel_MET_DP169744.jpg.webp)

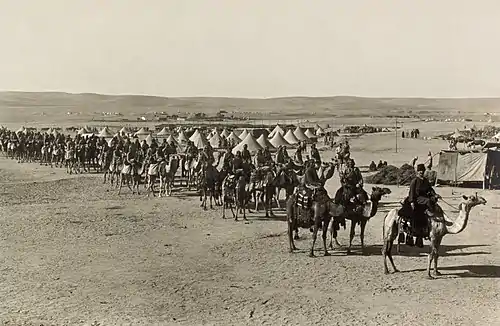

Napoleon employed a camel corps for his French campaign in Egypt and Syria. During the late 19th and much of the 20th centuries, camel troops were used for desert policing and patrol work in the British, French, German, Spanish and Italian colonial armies.

Descendants of such units still form part of the modern Moroccan, Egyptian armies and Indian paramilitary

The British-officered Egyptian Camel Corps played a significant role in the 1898 Battle of Omdurman;[12] one of the few occasions during this period when this class of mounted troops took part in substantial numbers in a set-piece battle. The Ottoman Army maintained camel companies as part of its Yemen and Hejaz Corps, both before and during World War I.

The Italians used Dubat camel troops in their Somalia Italiana, mainly for frontier patrol during the 1920s and 1930s. These Dubats participated in the Italian conquest of the Ethiopian Ogaden in 1935-1936 during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War.

The colonial authorities in Spanish Morocco used locally recruited camel troops in their northern part of Morocco, mainly for frontier patrol work from the 1930s until 1956. Forming part of the Tropas Nomades del Sahara, these camel mounted units had a limited local role in the Spanish Civil War during 1936-1939.;[13]

Camels are still used by the Jordanian Desert Patrol.[14]

The Bikaner Camel Corps of India's para-military Border Security Force also retain camels and use them to patrol borders.

See also

- Bikaner Camel Corps (Indian)

- Camel archer

- Dromedarii (Roman)

- Imperial Camel Corps (British Empire)

- Méhariste (French)

- Somaliland Camel Corps

- Sudan Defence Force

- Tropas Nómadas (Spanish)

- United States Camel Corps

- Zaptié (Italian)

- Dubats (Italian)

- Zamburak (camel mounted artillery)

References

- Herodotus (440 BC). The History of Herodotus. Rawlinson, George (trans.). Retrieved 4 December 2012.

He collected together all the camels that had come in the train of his army to carry the provisions and the baggage, and taking off their loads, he mounted riders upon them accoutred as horsemen. These he commanded to advance in front of his other troops against the Lydian horse; behind them were to follow the foot soldiers, and last of all the cavalry. When his arrangements were complete, he gave his troops orders to slay all the other Lydians who came in their way without mercy, but to spare Croesus and not kill him, even if he should be seized and offer resistance. The reason why Cyrus opposed his camels to the enemy's horse was because the horse has a natural dread of the camel, and cannot abide either the sight or the smell of that animal. By this stratagem he hoped to make Croesus's horse useless to him, the horse being what he chiefly depended on for victory. The two armies then joined battle, and immediately the Lydian war-horses, seeing and smelling the camels, turned round and galloped off; and so it came to pass that all Croesus' hopes withered away.

- "Cameliers and camels at war". New Zealand History online. History Group of the New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 30 August 2009. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- Jim Hicks, page 21 "The Persians", Time-Life Books, 1975

- Herodian of Antioch, History of the Roman Empire (1961) pp.108-134. Book 4. CHAPTER XIV

- D'Amato, Rafaele. Roman Army Units in the Eastern Provinces (1). p. 41. ISBN 978-1-4728-2176-8.

- Esposito, Gabriele. The Late Roman Army. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-9963657-9-6.

- Nicolle, David. Rome's Enemies 5. The Desert Frontier. pp. 20 & 21. ISBN 1-85532-166-1.

- Rocca, Samuel. The Army of Herod the Great. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-84603-206-6.

- Nicolle, David. Rome's Enemies 5. The Desert Frontier. pp. 34 & 37. ISBN 1-85532-166-1.

- Mubarakpuri, Saifur Rahman Al (2005), The sealed nectar: biography of the Noble Prophet, Darussalam Publications, p. 246, ISBN 978-9960-899-55-8

- Nicolle, David. The Armies of Islam 7th-11thm Centuries. p. 11. ISBN 085045-448-4.

- Tauris, I. B. Kitchener. Hero and Anti-Hero. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-1-78453-350-2.

- Jose M. Bueno, pages 155-156, Uniformes Militares de la Guerra Civil Espanola, Liberia Editorial San Martin, Madrid 1971

- Jordan's Bedouin 'desert forces' - Middle East - Al Jazeera English. 2010