Battle of Omdurman

At the Battle of Omdurman (2 September 1898), an army commanded by the British General Sir Herbert Kitchener defeated the army of Abdullah al-Taashi, the successor to the self-proclaimed Mahdi, Muhammad Ahmad. Kitchener was seeking revenge for the 1885 death of General Gordon.[3] It was a demonstration of the superiority of a highly disciplined army equipped with modern rifles, machine guns, and artillery over a force twice its size armed with older weapons, and marked the success of British efforts to re-conquer the Sudan. However, it was not until the 1899 Battle of Umm Diwaykarat that the final Mahdist forces were defeated.

| Battle of Omdurman | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mahdist War | |||||||

"The charge of the 21st Lancers" by Edward Matthew Hale. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Mahdist Sudan | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Sir Herbert Kitchener | Abdullah al-Taashi | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

8,200 British, 17,600 Sudanese and Egyptian soldiers | 52,000 warriors | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

47[1]–48[2] dead 382 wounded |

12,000 killed[1] 13,000 wounded 5,000 captured | ||||||

Omdurman is today a suburb of Khartoum in central Sudan, with a population of some 2 million. The village of Omdurman was chosen in 1884 as the base of operations by the Mahdi, Muhammad Ahmad. After his death in 1885, following the successful siege of Khartoum, his successor (Khalifa) Abdullah retained it as his capital.

Battle account

The battle took place at Kerreri, 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) north of Omdurman. Kitchener commanded a force of 8,000 British regulars and a mixed force of 17,000 Sudanese and Egyptian troops. He arrayed his force in an arc around the village of Egeiga, close to the bank of the Nile, where a twelve gunboat flotilla waited in support,[3] facing a wide, flat plain with hills rising to the left and right. The British and Egyptian cavalry were placed on either flank.

Abdullah's followers, calling themselves the Ansar and known to the British as the Dervishes, numbered around 50,000,[1] including some 3,000 cavalry. They were split into five groups—a force of 8,000 under Osman Azrak was arrayed directly opposite the British, in a shallow arc along a mile (1.6 km) of a low ridge leading onto the plain, and the other Mahdist forces were initially concealed from Kitchener's force. Abdullah al-Taashi[1] and 17,000 men were concealed behind the Surgham Hills to the west and rear of Osman Azrak's force, with 20,000 more positioned to the north-west, close to the front behind the Kerreri hills, commanded by Ali wad Hilu and Osman Sheikh ed-Din. A final force of around 8,000 was gathered on the slope on the right flank of Azrak's force.

The battle began in the early morning, at around 6:00 a.m. After the clashes of the previous day, the 8,000 men under Osman Azrak advanced straight at the waiting British, quickly followed by about 8,000 of those waiting to the northwest, a mixed force of rifle and spear-men. The 52 quick firing guns of the British artillery opened fire at around 2,750 metres (1.71 mi),[4] inflicting severe casualties on the Mahdist forces before they even came within range of the Maxim guns and volley fire. The frontal attack ended quickly, with around 4,000 Mahdist forces casualties; none of the attackers got closer than 50 m to the British trenches. A flanking move from the Ansar right was also checked, and there were bloody clashes on the opposite flank that scattered the Mahdist forces there.

While the Anglo-Egyptian infantry were able to make use of their superior firepower from behind a zariba barricade without suffering significant casualties, the cavalry and camel corps deployed to the centre-north of the main force found themselves under threat from the Mahadist Green Standard force of about 15,000 warriors. The commander of the Anglo-Egyptian mounted troops Lieutenant Colonel R.G. Broadwood used his cavalry to draw off part of the advancing Ansar attackers under Osman Digna but the slower-moving camel troops, attempting to regain the protection of the zariba, found themselves being closely pursued by Green Standard horsemen. This marked a crucial stage of the battle but Kitchener was able to deploy two gunboats to a position on the river where their cannon and Nordenfelt guns broke up the Mahadist force before it could destroy Broadwood's detachment and possibly penetrate the flank of the Anglo-Egyptian infantry.[5]

Kitchener was anxious to occupy Omdurman before the remaining Mahdist forces could withdraw there. He advanced his army on the city, arranging them in separate columns for the attack. The British light cavalry regiment, the 21st Lancers, was sent ahead to clear the plain to Omdurman. They had a tough time of it. In what has been described as the last operational cavalry charge by British troops, the 400-strong regiment attacked what they thought were only a few hundred dervishes, but in fact there were 2,500 infantry hidden behind them in a depression. After a fierce clash, the Lancers drove them back (resulting in three Victoria Crosses being awarded to Lancers who helped rescue wounded comrades).[6] One of the participants of this fight was Lieutenant Winston Churchill.[6] On a larger scale, the British advance allowed the Khalifa to re-organize his forces. He still had over 30,000 men in the field and directed his main reserve to attack from the west while ordering the forces to the northwest to attack simultaneously over the Kerreri Hills.

Kitchener's force wheeled left in echelon to advance up Surgham ridge and then southwards. To protect the rear, a brigade of 3,000 mainly Sudanese, commanded by Hector MacDonald, was reinforced with Maxims and artillery and followed the main force at around 1,350 metres (0.84 mi). Curiously, the supplies and wounded around Egeiga were left almost unprotected.

MacDonald was alerted to the presence of around 15,000 enemy troops moving towards him from the west, out from behind Surgham. He wheeled his force and lined them up to face the enemy charge. The Mahdist infantry attacked in two prongs. Lewis's Egyptian Brigade managed to hold its own[4] but MacDonald was forced to repeatedly re-order his battalions. The brigade maintained a punishing fire. Kitchener, now aware of the problem, "began to throw his brigades about as if they were companies".[7] MacDonald's brigade was soon reinforced with flank support and more Maxim guns and the Mahdist forces were forced back; they finally broke and fled or died where they stood. The Mahdist forces to the north had regrouped too late and entered the clash only after the force in the central valley had been routed. They pressed Macdonald's Sudanese brigades hard, but Wauchope's brigade with the Lincolnshire Regiment was quickly brought up and with sustained section volleys repulsed the advance. A final desperate cavalry charge of around 500 horsemen was utterly destroyed. The march on Omdurman was resumed at about 11:30.

Awards

![]() Four awards were made of the Victoria Cross, all for gallantry shown on 2 September 1898.

Four awards were made of the Victoria Cross, all for gallantry shown on 2 September 1898.

- Thomas Byrne, Private, 21st Lancers

- Raymond de Montmorency, Lieutenant, 21st Lancers

- Paul Aloysius Kenna, Captain, 21st Lancers

- Nevill Smyth, Captain, 2nd Dragoon Guards (Queen's Bays), attached to the Egyptian Army.[8]

![]() Queen's Sudan Medal, British campaign medal awarded to British and Egyptian forces which took part in the Sudan campaign between 1896 and 1898.

Queen's Sudan Medal, British campaign medal awarded to British and Egyptian forces which took part in the Sudan campaign between 1896 and 1898.

![]() Khedive's Sudan Medal (1897), Egyptian campaign medal awarded to British and Egyptian forces which took part in the Sudan campaign between 1896 and 1898.

Khedive's Sudan Medal (1897), Egyptian campaign medal awarded to British and Egyptian forces which took part in the Sudan campaign between 1896 and 1898.

Aftermath

Around 12,000 Muslim warriors were killed, 13,000 wounded and 5,000 taken prisoner. Kitchener's force lost 47 men killed and 382 wounded, the majority from MacDonald's command. One eyewitness described the appalling scene:

They could never get near and they refused to hold back. ... It was not a battle but an execution. ... The bodies were not in heaps—bodies hardly ever are; but they spread evenly over acres and acres. Some lay very composedly with their slippers placed under their heads for a last pillow; some knelt, cut short in the middle of a last prayer. Others were torn to pieces ...

The battle was the first time that the Mark IV hollow point bullet, made in the arsenal in Dum Dum, was used in a major battle. It was an expanding bullet, and the units that used it considered them to be highly effective.[9]

Controversy over the killing of the wounded after the battle began soon afterwards.[10] The debate was ignited by a highly critical article published by Ernest Bennett (present at the battle as a journalist) in the Contemporary Review, which evoked a fierce riposte and defense of Kitchener by Bennet Burleigh (another journalist also present at the battle).[11] Winston Churchill privately agreed with Bennett that Kitchener was too brutal in his killing of the wounded.[12] This opinion was reflected in his own account of the battle when it was first published in 1899.[13] However, mindful of the effect that patriotic public opinion could have on his political career, Churchill significantly moderated criticism of Kitchener in his book's second edition in 1902.

The Khalifa, Abdullah al-Taashi, escaped and survived until 1899, when he was killed in the Battle of Umm Diwaykarat.

Several days after the battle, Kitchener was sent to Fashoda, due to the developing Fashoda Incident.

Kitchener was ennobled as a baron, Kitchener of Khartoum, for his victory. Four Victoria Crosses were awarded, three to members of the 21st Lancers, as a result of this action: 2nd Lieutenant Raymond H.L.J. De Montmorency, Captain Paul A. Kenna, Private Thomas Byrne and one to Captain Nevill Smyth of the 2nd Dragoon Guards (Queen's Bays).[14]

Winston Churchill was present at the battle and he rode with the 21st Lancers. He published his account of the battle in 1899 as "The River War: An Account of the Reconquest of the Soudan". Present as a war correspondent for The Times was Colonel Frank Rhodes, brother of Cecil, who was shot and severely wounded in the right arm. For his services during that battle he was restored to the army active list.

The Battle of Omdurman has also lent its name to many streets in British and Commonwealth cities, for example 'Omdurman Road' in Southampton and 'Omdurman Street' in Freshwater, Sydney, Australia.

Fictional accounts

The 1939 film adaptation of the novel The Four Feathers is set in the time of this battle, and covers other aspects of the Sudan Campaign.

The 2008 novel After Omdurman by John Ferry is partly set during the 1898 re-conquest of the Sudan, with the book's lead character, Evelyn Winters, playing a peripheral role in the Battle of Omdurman.

In the British television sitcom Dad's Army, the character of Corporal Jones often refers to the days he spent serving under General Kitchener at the Battle of Omdurman. In the episode called The Two and a Half Feathers there is an extended flashback to the days directly before the battle, narrated by Jones.

The 1972 film Young Winston includes a depiction of the initial Anglo-Egyptian artillery bombardment at the start of the battle as well as a recreation of the charge of the 21st Lancers.

The 2009 novel The Devil's Paintbrush by Jake Arnott involves a retelling of the life of Hector MacDonald, and includes the battle and Kitchener's railway-building drive through Sudan.

The 2005 novel The Triumph of the Sun by Wilbur Smith depicts the siege of Khartoum and the Battle of Omdurman with a mixture of historical and fictional characters

The novel With Kitchener in the Soudan by G.A. Henty tells the story of the British military expedition and the destruction of the Mahdi's followers during the Mahdist War (1881–1899). It was first published in 1903.

The Murdoch Mysteries episodes Winston's Lost Night has a young Winston Churchill mention the battle several times, considering it to be a one-sided massacre where the Britons had an unfair advantage. The murder victim, a friend of Churchill's, was one of the officers who descretated the tomb of Muhammad Ahmad afterwards, using his skull as an ink pot. The murderer is a Sudanese veteran of Taashi's army who was motivated by vengeance for this disrespect.

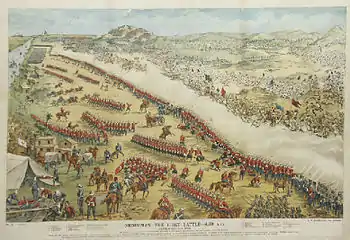

In art

The subject of the battle made its appearance in several oil paintings exhibited in Britain at the time. In particular, the charge of the 21st Lancers held special appeal and several artists portrayed the scene including Stanley Berkeley, Robert Alexander Hillingford, Richard Caton Woodville, William Barnes Wollen, Gilbert S. Wright, Edward Mathew Hale, Capt. Adrian Jones, Major John C. Mathews, and Allan Stewart.[15] The pictorial press covered the campaign extensively and employed several artists to record the events.[16]

References

Citations

- "Sudanese honour warriors who fell fighting British". Sudan Tribune. 3 September 2005.

- Bunting, Tony. "Battle of Omdurman". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- "This Sceptred Isle, Battle of Omdurman 1898, Episode 68". BBC.

- "Omdurman 1898". Obscure Battles. blogspot.com.

- Faught, C. Brad (2016). Kitchener. Hero and Anti-Hero. I.B. Tauris. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-1-78453-350-2.

- "Charge of the 21st Lancers at Omdurman, 2 September 1898". Army Museum. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- Churchill, Winston S. (1898). The Battle of Omdurman.

- Winston Churchill (1899). The River War Volume 2. Longmans. p. 199.

- "Dum Dums". Archived from the original on 25 September 2008.

- Treatment of wounded at Omdurman Hansard

- "After Omdurman", E. N. Bennett, Contemporary Review, Vol. 75, 1899. Bennett subsequently published a book on the battle, The Downfall of the Dervishes, E.N. Bennett, Methuen, London, 1899.

- Winston S. Churchill, Randolph S. Churchill, Companion Volume 1, Part 2, Heinemann, 1967, page 1004.

- The River War: An Account of the Reconquest of the Soudan, Churchill

- "No. 27023". The London Gazette. 15 November 1898. p. 6688.

- Harrington, Peter (1993). British Artists and War: The Face of Battle in Paintings and Prints, 1700–1914. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-157-6

- Harrington, Peter, "Images and Perceptions: Visualising the Sudan Campaign," in Edward M. Spiers (ed.), Sudan: The Reconquest Reappraised. London: Frank Cass, 1998, pp. 82–101. ISBN 0-7146-4749-7.

Sources

- Ellis, John (1981) [1975]. The Social History of the Machine Gun. New York, NY: Arno Press.

Further reading

- Asher, Michael (2005). Khartoum: The Ultimate Imperial Adventure. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-025855-8.

- Brighton, Terry (1998). The Last Charge: the 21st Lancers and the Battle of Omdurman. Marlborough: Crowood. ISBN 1-86126-189-6

- Churchill, Winston Spencer (2008) [two-volume unabridged version by Longmans & Green in 1899, abridged to one volume in 1902]. River War: An Historical Account of The Reconquest of the Soudan. St. Augustine's Press. ISBN 1-58731-700-1. Also available at the Gutenberg Project

- Dutton, Roy (2012). Forgotten Heroes – The Charge of the 21st Lancers at Omdurman. London: Infodial. ISBN 978-0-9556554-5-6.

- Featherstone, Donald (1993). Omdurman 1898: Kitchener's Victory in the Sudan. London: Osprey. ISBN 1-85532-368-0.

- Ferry, John (2008). After Omdurman. London: Robert Hale. ISBN 0-7090-8516-8.

- Harrington, Peter, and Frederic A. Sharf (ed.) (1998). Omdurman 1898: The Eyewitnesses Speak. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-333-1.

- Meredith, John (1998). Omdurman Diaries 1898: Eyewitness Accounts of the Legendary Campaign. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 0-85052-607-8

- Spiers, Edward M. (ed.) (1999). Sudan: The Reconquest Reappraised. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 0-7146-4749-7

- Ziegler, Philip (1974). Omdurman. New York: Knoff. ISBN 0-394-48936-5.

- Zulfo, I.H. (1980). Karari: The Sudanese Account of the Battle of Omdurman. Warne. ISBN 0-7232-2677-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Omdurman. |

- Battle of Omdurman Original reports from The Times

- Om Der Man! – an overview of the battle by the War Nerd

- Sudanese honour warriors who fell fighting British – A report from battle commemoration, originally by Reuters

- Bennet Burleigh, Khartoum Campaign or the Re-conquest of the Soudan, 1898