Camorra in New York City

The Brooklyn Camorra or New York Camorra was a loose grouping of early-20th-century organized crime groups that formed among Italian immigrants originating in Naples and the surrounding Campania region living in Greater New York, particularly in Brooklyn.[1] In the early 20th century, the criminal underworld of New York City consisted largely of Italian Harlem-based Sicilians and groups of Neapolitans from Brooklyn, sometimes referred to as the Brooklyn Camorra, as Neapolitan organized crime is referred to as the Camorra.[1]

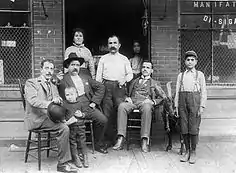

The Navy Street Gang, one of the Camorra groups in Brooklyn | |

| Founding location | Brooklyn, New York City |

|---|---|

| Years active | 1885-1918 |

| Territory | Brooklyn and East Harlem |

| Ethnicity | Neapolitan American |

| Criminal activities | Various criminal rackets, mainly extortion, policy game, and wholesale fruit and vegetable markets. |

Background

The substantial population of the New York Italian immigrant community offered plentiful economic opportunities. At the turn of the century, some 500,000 Italians, mainly originating from the impoverished southern regions of Italy, lived in New York City and had to survive in difficult social and economic circumstances.[2][3] A New York Times article in 1885 mentions the presence of the Camorra in New York, involved in extortion and immigrant and labor racketeering.[4]

Italian immigration “made fortunes for speculators and landlords, but it also transformed the neighborhood into a kind of human ant heap in which suffering, crime, ignorance and filth were the dominant elements,” according to historian Arrigo Petacco.[3] According to sociologist Humbert S. Nelli: “New York’s Italian community offered a lucrative market for illicit activities, particularly gambling and prostitution. It also provided a huge market for products from the homeland and from the West Coast, such as artichokes and olive oil, the distribution of which the criminal elements attempted to control.”[2]

Early crime bosses

The cheap labor needed for the expansion of capitalism of that time was made available by the scores of poor Italian immigrants. Like earlier immigrant generations, a few Sicilians and Neapolitans engaged in criminal activities to succeed, employing the crime traditions from their original Italian home regions.[3] One of the prominent crime bosses was Enrico Alfano, who became one of the principal underworld targets of police sergeant Joseph Petrosino, the head of the Italian Squad of the New York City Police Department.[5] Another prominent criminal boss around 1910-15 was Giosue Gallucci, the undisputed King of Little Italy born in Naples, who employed Neapolitan and Sicilian street gangs as his enforcers for the Italian lottery or numbers game and enjoyed functional immunity from law enforcement through his political contacts.[2][3]

Apart from them there were different Camorra gangs in New York. The gangs had their roots in the Neapolitan Camorra, but most members were American born.[1] The two New York based Camorra groups were the Neapolitan Navy Street gang headed by Alessandro Vollero and Leopoldo Lauritano, and the Neapolitan Coney Island gang under the command of Pellegrino Morano who ran his activities from his Santa Lucia restaurant in Coney Island.

Vollero and Lauritano owned a coffee house at 133 Navy Street in Brooklyn. The coffee house was used as the headquarters for their gang, which mainly consisted of Neapolitans, and was often referred to as The Camorra.[6] Morano opened the Santa Lucia restaurant close to the Coney Island amusements parks with his right-hand men Tony Parretti,[7] from where his gang made money in gambling and cocaine dealing.[8][9] The gangs were not tightly led organizations, but rather loose associations where everybody worked for himself, although Morano was one of the leaders that initiated recruits as camorristi.[7][10]

Both gangs initially worked together against the Morello crime family from Italian Harlem for control of the New York rackets. The Camorra groups tried to muscle in the lucrative artichoke business, but the wholesale dealers resisted their threats. In the end, a deal was negotiated in which a ‘tax’ of 25 dollars was levied on every car load of artichokes delivered, under threat of stealing the dealer's horses or wrecking their merchandise.[11] Coal and ice merchants also proved hard to extort, and the business gains of the groups were not as large as they expected. Eventually, they were decimated when their own members turned against them.[12]

Mafia-Camorra War

The fight over the control of the New York rackets is known as the Mafia–Camorra War and started after the killing of Giosue Gallucci and his son on May 17, 1915.[2][13] The violence and string of murders prompted a reaction from the authorities. Police convinced Ralph Daniello to testify against his former associates of the Brooklyn Navy Street gang. He provided evidence about 23 murders.[14] Several Grand Juries issued 21 indictments in November 1917.[12][15][16] At the trials, some criminals involved depicted the Navy Street and Coney Island gangs as "Camorra" and used "Mafia" to identify the groups from East Harlem.[15]

The trials in 1918 entirely dismantled the Navy Street gang. Testimonies of their own associates destroyed the internal protection against law enforcement they once enjoyed. The demise of the gangs meant the end of the Camorra in New York and the rise in power of their rivals, the American-based Sicilian Mafia groups.[12] Following the downfall of the New York Camorra, Neapolitan or Campanian organized crime groups in New York were absorbed into or merged with the newly dominant Sicilian Mafia groups in New York, creating the modern Italian-American Mafia, which would increasingly consist of not only Sicilians but Italian and Italian-American criminals from various Italian regions. Future Italian-American gangsters that originated from Naples or Campania, like Vito Genovese, operated in Italian-American Mafia families, in which an Italian-American gangster's exact Italian region of origin had little importance as long as he was of Italian origin.

References

- Critchley, The Origin of Organized Crime in America, p. 105

- Nelli, The Business of Crime, pp. 129-31

- Abadinsky, Organized Crime, pp. 81-82

- Italians Imposed Upon; A Branch of the Camorra Said To Be Established in New-York, The New York Times, February 21, 1885

- Romano, Italian Americans in Law Enforcement, p. 45

- Pelligrino Morano, GangRule.com

- Critchley, The Origin of Organized Crime in America, p. 118

- Nelli, The Business of Crime, pp. 131-33

- Dash, The First Family, p. 252

- Relates Camorra Degree in Court The Daily Standard Union (Brooklyn), May 8, 1918

- Critchley, The Origin of Organized Crime in America, p. 122

- The Struggle for Control, GangRule.com

- Father and Son Shot, The New York Times, May 18, 1915

- Confession May Clear 23 Feud Murders, The New York Times, November 28, 1917

- Nelli, The Business of Crime, pp. 133-134

- Indict Twelve In Murder Conspiracy, The New York Times, December 1, 1917

Sources

- Abadinsky, Howard (2010). Organized Crime (Ninth Edition), Belmont (CA): Wadsworth, ISBN 978-0-495-59966-1

- Critchley, David (2009). The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891-1931, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-99030-0

- Dash, Mike (2009). The First Family: Terror, Extortion, Revenge, Murder, and the Birth of the American Mafia, New York: Random House, ISBN 978-1-4000-6722-0

- Nelli, Humbert S. (1981). The Business of Crime. Italians and Syndicate Crime in the United States, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press ISBN 0-226-57132-7 (Originally published in 1976)

- Romano, Anne T. (2010). Italian Americans in Law Enforcement, Xlibris Corporation, ISBN 978-1-4535-5881-2