Captivity narrative

Captivity narratives are usually stories of people captured by enemies whom they consider uncivilized, or whose beliefs and customs they oppose. The best-known captivity narratives in North America are those concerning Europeans and Americans taken as captives and held by the indigenous peoples of North America. These narratives have had an enduring place in literature, history, ethnography, and the study of Native peoples.

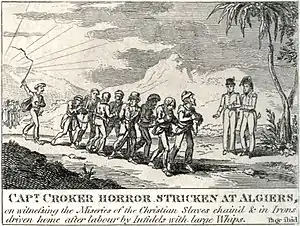

They were preceded, among English-speaking peoples, by publication of captivity narratives related to English taken captive and held by Barbary pirates, or sold for ransom or slavery. Others were taken captive in the Middle East. These accounts established some of the major elements of the form, often putting it within a religious framework, and crediting God or Providence for gaining freedom or salvation. Following the North American experience, additional accounts were written after British people were captured during exploration and settlement in India and East Asia.

Since the late 20th century, captivity narratives have also been studied as accounts of persons leaving, or held in contemporary religious cults or movements, thanks to scholars of religion like David G. Bromley and James R. Lewis.

Traditionally, historians have made limited use of many captivity narratives. They regarded the genre with suspicion because of its ideological underpinnings. As a result of new scholarly approaches since the late 20th century, historians with a more certain grasp of Native American cultures are distinguishing between plausible statements of fact and value-laden judgments in order to study the narratives as rare sources from "inside" Native societies.[1]

In addition, modern historians such as Linda Colley and anthropologists such as Pauline Turner Strong have also found the North American narratives useful in analyzing how the colonists or settlers constructed the "other". They also assess these works for what the narratives reveal about the settlers' sense of themselves and their culture, and the experience of crossing the line to another. Colley has studied the long history of English captivity among other cultures, both the Barbary pirate captives who preceded those in North America, and British captives in cultures such as India or East Asia, which began after the early North American experience.

Certain North American captivity narratives related to being held among Native peoples were published from the 18th through the 19th centuries. They reflected an already well-established genre in English literature, which some colonists would likely have been familiar with. There had already been numerous English accounts of captivity by Barbary pirates.

Other types of captivity narratives, such as those recounted by apostates from religious movements (i.e. "cult survivor" tales), have remained an enduring topic in modern media. They have been published in books, and periodicals, in addition to being the subjects of film and television programs, both fiction and non-fiction.[2]

Background

Because of the competition between New France and New England in North America, raiding between the colonies was frequent. Colonists in New England were frequently taken captive by Canadiens and their Indian allies (similarly, the New Englanders and their Indian allies took Canadiens and Indian prisoners captive). According to Kathryn Derounian-Stodola, statistics on the number of captives taken from the 15th through the 19th centuries are imprecise and unreliable, since record-keeping was not consistent and the fate of hostages who disappeared or died was often not known.[3] Yet conservative estimates run into the thousands, and a more realistic figure may well be higher. Between King Philip's War (1675) and the last of the French and Indian Wars (1763), approximately 1,641 New Englanders were taken hostage.[4] During the decades-long struggle between whites and Plains Indians in the mid-19th century, hundreds of women and children were captured.[5]

Many narratives included a theme of redemption by faith in the face of the threats and temptations of an alien way of life. Barbary captivity narratives, accounts of English people captured and held by Barbary pirates, were popular in England in the 16th and 17th centuries. The first Barbary captivity narrative by a resident of North America was that of Abraham Browne (1655). The most popular was that of Captain James Riley, entitled An Authentic Narrative of the Loss of the Brig Commerce (1817).

Jonathan Dickinson's Journal, God's Protecting Providence ... (1699), is an account by a Quaker of shipwreck survivors captured by Indians in Florida. He says they survived by placing their trust in God to protect them. The Cambridge History of English and American Literature describes it as, "in many respects the best of all the captivity tracts."[6]

Ann Eliza Bleecker's epistolary novel, The History of Maria Kittle (1793), is considered the first known captivity novel. It set the form for subsequent Indian capture novels.[7]

Origins of narratives

New England and the Southern colonies

American Indian captivity narratives, accounts of men and women of European descent who were captured by Native Americans, were popular in both America and Europe from the 17th century until the close of the United States frontier late in the 19th century. Mary Rowlandson's memoir, A Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, (1682) is a classic example of the genre. According to Nancy Armstrong and Leonard Tennenhouse, Rowlandson's captivity narrative was "one of the most popular captivity narratives on both sides of the Atlantic."[8] Although the text temporarily fell out of print after 1720, it had a revival of interest in the 1780s. Other popular captivity narratives from the late 17th century include Cotton Mather's The Captivity of Hannah Dustin (1696–97), a well-known account that took place during King William's War, and Jonathan Dickinson's God's Protecting Providence (1699).

American captivity narratives were usually based on true events, but they frequently contained fictional elements as well. Some were entirely fictional, created because the stories were popular. One spurious captivity narrative was The Remarkable Adventures of Jackson Johonnet, of Massachusetts (Boston, 1793).

Captivity in another culture brought into question many aspects of the captives' lives. Reflecting their religious beliefs, the Puritans tended to write narratives that negatively characterized Indians. They portrayed the trial of events as a warning from God concerning the state of the Puritans' souls, and concluded that God was the only hope for redemption. Such a religious cast had also been part of the framework of earlier English accounts of captivity by Barbary pirates. The conflict between the English colonists and the French and Indians led to the emphasis of Indians' cruelty in English captivity narratives, to inspire hatred for their enemies.[9] In William Flemming's Narrative of the Sufferings (1750), Indian barbarities are blamed on the teachings of Roman Catholic priests.[9]

During Queen Anne's War, French and Abenaki warriors made the Raid on Deerfield in 1704, killing many settlers and taking more than 100 persons captive. They were taken on a several hundred-mile overland trek to Montreal. Many were held there in Canada for an extended period, with some captives adopted by First Nations families and others held for ransom. In the colonies, ransoms were raised by families or communities; there was no higher government program to do so. The minister John Williams was among those captured and ransomed. His account, The Redeemed Captive (1707), was widely distributed in the 18th and 19th centuries, and continues to be published today. Due to his account, as well as the high number of captives, this raid, unlike others of the time, was remembered and became an element in the American frontier story.[10]

During Father Rale's War, Indians raided Dover, New Hampshire. Elizabeth Hanson wrote a captivity narrative after gaining return to her people. Susannah Willard Johnson of New Hampshire wrote about her captivity during the French and Indian War (the North American front of the Seven Years' War).

In the final 30 years of the 18th century, there was a revival of interest in captivity narratives. Accounts such as A Narrative of the Capture and Treatment of John Dodge, by the English at Detroit (1779), A Surprising Account, of the Captivity and Escape of Philip M'Donald, and Alexander M'Leod, of Virginia, from the Chickkemogga Indians (1786), Abraham Panther's A Very Surprising Narrative of a Young Woman, Who Was Discovered in a Rocky Cave (1787), Narrative of the Remarkable Occurrences, in the Life of John Blatchford of Cape-Ann (1788), and A Narrative of the Captivity and Sufferings of Mr. Ebenezer Fletcher, of Newipswich, Who Was ... Taken Prisoner by the British (1798) provided American reading audiences with new narratives. In some accounts, British soldiers were the primary antagonists.

Nova Scotia and Acadia

%252C_Nova_Scotia.jpg.webp)

Seven captivity narratives are known that were written following capture of colonists by the Mi'kmaq and Maliseet tribes in Nova Scotia and Acadia (two other prisoners were future Governor Michael Francklin (taken 1754) and Lt John Hamilton (taken 1749) at the Siege of Grand Pre. Whether their captivity experiences were documented is unknown).

The most well-known became that by John Gyles, who wrote Memoirs of odd adventures, strange deliverances, &c. in the captivity of John Gyles, Esq; commander of the garrison on St. George's River (1736). He was captured in the Siege of Pemaquid (1689). He wrote about his torture by the Natives at Meductic village during King William's War. His memoirs are regarded as a precursor to the frontier romances of James Fenimore Cooper, William Gilmore Simms, and Robert Montgomery Bird.[11]

Merchant William Pote was captured during the siege of Annapolis Royal during King George's War and wrote about his captivity. Pote also wrote about being tortured. Ritual torture of war captives was common among Native American tribes, who used it as a kind of passage.[12]

Henry Grace was taken captive by the Mi'kmaq near Fort Cumberland during Father Le Loutre's War. His narrative was entitled, The History of the Life and Sufferings of Henry Grace (Boston, 1764).[13] Anthony Casteel was taken in the Attack at Jeddore during the same war, and also wrote an account of his experience.[14]

The fifth captivity narrative, by John Payzant, recounts his being taken prisoner with his mother and sister in the Maliseet and Mi`kmaq Raid on Lunenburg (1756) during the French and Indian War. After four years of captivity, his sister decided to remain with the natives. In a prisoner exchange, Payzant and his mother returned to Nova Scotia. John Witherspoon was captured at Annapolis Royal during the French and Indian War and wrote about his experience.[15]

During the war Gamaliel Smethurst was captured; he published an account in 1774.[16] Lt. Simon Stephens, of John Stark's ranger company, and Captain Robert Stobo escaped together from Quebec along the coast of Acadia, finally reaching British-occupied Louisbourg and wrote accounts.[17][18]

During the Petitcodiac River Campaign, the Acadian militia took prisoner William Caesar McCormick of William Stark's rangers and his detachment of three rangers and two light infantry privates from the 35th. The Acadian militia took the prisoners to Miramachi and then Restogouch.[19] (They were kept by Pierre du Calvet who later released them to Halifax.)[20] In August 1758, William Merritt was taken captive close to St. Georges (Thomaston, Maine), and taken to the Saint John River and later to Quebec.[21]

North Africa

North America was not the only region to produce captivity narratives. North African slave narratives were written by white Europeans and Americans who were captured, often as a result of shipwrecks, and enslaved in North Africa in the 18th and early 19th centuries. If the Europeans converted to Islam and adopted North Africa as their home, they could often end their slavery status, but such actions disqualified them from being ransomed to freedom by European consuls in Africa, who were qualified only to free captives who had remained Christians.[22] About 20,000 British and Irish captives were held in North Africa from the beginning of the 17th century to the middle of the 18th, and roughly 700 Americans were held captive as North African slaves between 1785 and 1815. The British captives produced 15 full biographical accounts of their experiences, and the American captives produced more than 100 editions of 40 full-length narratives.[23]

Types

Assimilated captives

In his book Beyond Geography: The Western Spirit Against the Wilderness (1980), Frederick W. Turner discusses the effect of those accounts in which white captives came to prefer and eventually adopt a Native American way of life; they challenged European-American assumptions about the superiority of their culture. During some occasions of prisoner exchanges, the white captives had to be forced to return to their original cultures. Children who had assimilated to new families found it extremely painful to be torn from them after several years' captivity. Numerous adult and young captives who had assimilated chose to stay with Native Americans and never returned to live in Anglo-American or European communities. The story of Mary Jemison, who was captured as a young girl (1755) and spent the remainder of her 90 years among the Seneca, is such an example.

Where The Spirit Lives, a 1989 film written by Keith Leckie and directed by Bruce Pittman, turns the tables on the familiar white captive/aboriginal captors narrative. It sensitively portrays the plight of Canadian aboriginal children who were captured and sent to residential schools, where they were stripped of their Native identity and forced to conform to Eurocentric customs and beliefs.

The story of Patty Hearst, which unfolded primarily in the mid-1970s, represents a special case. She was initially captured by a domestic U.S. terror group called the Symbionese Liberation Army in February, 1974. About a year later, she was photographed wielding a machine gun, helping them rob a bank. Was she an "assimilated captive" or was she only cooperating as a matter of survival? Was she "brainwashed" or fully conscious, acting with free will? These questions were hotly debated at the time.[24]

Anti-cult captivity narratives

Out of thousands of religious groups, a handful have become associated with acts of violence. This includes the Peoples Temple founded by Jim Jones in 1955, which ended in a murder/suicide claiming the lives of 918 people in November, 1978 in Guyana (see main article: Peoples Temple).

Members of the Peoples Temple who did not die in the murder/suicide are examples of "cult survivors", and the cult survivor meme has become a popular one. A recent American sitcom, Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, is premised on the notion of "cult survivor" as a social identity. It is not unusual for anyone who grew up in a religious and culturally conservative household – and who later adopted secular mainstream values – to describe themselves as a "cult survivor", notwithstanding the absence of any abuse or violence. In this sense, "cult survivor" may be used as a polemical term in connection with the so-called "culture war".

Not all anti-cult captivity narratives describe physical capture. Sometimes the capture is a metaphor, as is the escape or rescue. The "captive" may be someone who claims to have been "seduced" or "recruited" into a religious lifestyle which he/she retrospectively describes as one of slavery. The term "captive" may nonetheless be used figuratively.

Some captivity narratives are partly or even wholly fictional, but are meant to impart a strong moral lesson, such as the purported dangers of conversion to a minority faith. Perhaps the most notorious work in this subgenre is The Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk,[25] a fictional work circulated during the 19th century and beyond, and used to stoke anti-Catholic sentiment in the U.S. (see main article: Maria Monk).

She claimed to have been born into a Protestant family, but was exposed to Roman Catholicism by attending a convent school. She subsequently resolved to become a Catholic nun, but upon admission to the order at the Hôtel-Dieu nunnery in Montreal, was soon made privy to its dark secrets: the nuns were required to service the priests sexually, and the children born of such liaisons were murdered and buried in a mass grave on the building's premises. Though the Maria Monk work has been exposed as a hoax, it typifies those captivity narratives which depict a minority religion as not just theologically incorrect, but fundamentally abusive.

In Rape-Revenge Films: A Critical Study, Alexandra Heller-Nicholas writes:

The basic structure of the captivity narrative concerns the rescue of "helpless" maidens who have been kidnapped by "natives"[.] [They are] rescued at the last possible moment by a "hero." Commonly, this "hero" is rewarded through marriage. For James R. Lewis, the nineteenth century captivity narrative was intended to either entertain or titillate audiences, or to function as propaganda.[26]

Like James R. Lewis, David G. Bromley is a scholar of religion who draws parallels between the propaganda function of 19th century captivity narratives concerning Native peoples, and contemporary captivity narratives concerning new religious movements. Bromley notes that apostates from such movements frequently cast their accounts in the form of captivity narratives. This in turn provides justification for anti-cult groups to target religious movements for social control measures like deprogramming. In The Politics of Religious Apostasy, Bromley writes:

[T]here is considerable pressure on individuals exiting Subversive organizations to negotiate a narrative with the oppositional coalition that offers an acceptable explanation for participation in the organization and for now once again reversing loyalties. In the limiting case, exiting members without any personal grievance against the organization may find that re-entry into conventional social networks is contingent on at least nominally affirming such opposition coalition claims. The archetypal account that is negotiated is a "captivity narrative" in which apostates assert that they were innocently or naïvely operating in what they had every reason to believe was a normal, secure social site; were subjected to overpowering subversive techniques; endured a period of subjugation during which they experienced tribulation and humiliation; ultimately effected escape or rescue from the organization; and subsequently renounced their former loyalties and issued a public warning of the dangers of the former organization as a matter of civic responsibility. Any expressions of ambivalence or residual attraction to the former organization are vigorously resisted and are taken as evidence of untrustworthiness. Emphasis on the irresistibility of subversive techniques is vital to apostates and their allies as a means of locating responsibility for participation on the organization rather than on the former member.[27]

"Cult survivor" tales have become a familiar genre. They employ the devices of the captivity narrative in dramatic fashion, typically pitting mainstream secular values against the values held by some spiritual minority (which may be caricatured). As is true of the broader category, anti-cult captivity narratives are sometimes regarded with suspicion due to their ideological underpinnings, their formulaic character, and their utility in justifying social control measures. In addition, critics of the genre tend to reject the "mind control" thesis, and to observe that it is extremely rare in Western nations for religious or spiritual groups to hold anyone physically captive.[28]

Like captivity narratives in general, anti-cult captivity narratives also raise contextual concerns. Ethnohistoric Native American culture differs markedly from Western European culture. Each may have its merits within its own context. Modern theorists question the fairness of pitting one culture against another and making broad value judgments.

Similarly, spiritual groups may adopt a different way of life than the secular majority, but that way of life may have merits within its own context. Spiritual beliefs, rituals, and customs are not necessarily inferior simply because they differ from the secular mainstream. Anti-cult captivity narratives which attempt to equate difference with abuse, or to invoke a victim paradigm, may sometimes be criticized as unfair by scholars who believe that research into religious movements should be context-based and value-free.[29] Beliefs, rituals, and customs which we assumed were merely "primitive" or "strange" may turn out to have profound meaning when examined in their own context.[30]

Just as Where the Spirit Lives may be viewed as a "reverse" captivity narrative concerning Native peoples, the story of Donna Seidenberg Bavis (as recounted in The Washington Post[31]) may be viewed as a "reverse" captivity narrative concerning new religious movements. The typical contemporary anti-cult captivity narrative is one in which a purported "victim" of "cult mind control" is "rescued" from a life of "slavery" by some form of deprogramming or exit counseling. However, Donna Seidenberg Bavis was a Hare Krishna devotee (member of ISKCON) who – according to a lawsuit filed on her behalf by the American Civil Liberties Union – was abducted by deprogrammers in February 1977, and held captive for 33 days. During that time, she was subjected to abusive treatment in an effort to "deprogram" her of her religious beliefs. She escaped her captors by pretending to cooperate, then returned to the Krishna temple in Potomac, Maryland. She subsequently filed a lawsuit claiming that her freedom of religion had been violated by the deprogramming attempt, and that she had been denied due process as a member of a hated class.

Satanic captivity narratives

Among anti-cult captivity narratives, a subgenre is the Satanic Ritual Abuse story, the best-known example being Michelle Remembers.[32] In this type of narrative, a person claims to have developed a new awareness of previously unreported ritual abuse as a result of some form of therapy which purports to recover repressed memories, often using suggestive techniques.

Michelle Remembers represents the cult survivor tale at its most extreme. In it, Michelle Smith recounts horrific tales of sexual and physical abuse at the hands of the "Church of Satan" over a five-year interval. However, the book has been extensively debunked, and is now considered most notable for its role in contributing to the Satanic Ritual Abuse scare of the 1980s, which culminated in the McMartin preschool trial.

Children's novels inspired by captivity narratives

Captivity narratives, in addition to appealing to adults, have been attracting today's children as well. The narratives' exciting nature and their resilient young protagonists make for very educational and entertaining children's novels that have for goal to convey the "American characteristics of resourcefulness, hopefulness, pluck and purity".[33] Elizabeth George Speare published Calico Captive (1957), a historical fiction children's novel inspired by the captivity narrative of Susannah Willard Johnson. In Rewriting the Captivity Narrative for Contemporary Children: Speare, Bruchac, and the French and Indian War (2011), Sara L. Schwebel writes:

Johnson's Narrative vividly describes Susanna Johnson's forty-eight-month ordeal - the terror of being taken captive, childbirth during the forced march, prolonged separation from her three young children, degradation and neglect in a French prison, the loss of a newborn, a battle with smallpox, separation from her husband, and finally, widowhood as her spouse fell in yet another battle in the years-long French and Indian war. Spear borrowed heavily from Johnson's text, lifting both details and dialogue to construct her story. In pitching her tale to young readers, however, she focused not on the Narrative's tale of misfortune but on the youthful optimism of Susanna Johnson's largely imagined younger sister, Miriam.[33]

Conclusions

This article references captivity narratives drawn from literature, history, sociology, religious studies, and modern media. Scholars point to certain unifying factors. Of early Puritan captivity narratives, David L. Minter writes:

First they became instruments of propaganda against Indian "devils" and French "Papists." Later, ... the narratives played an important role in encouraging government protection of frontier settlements. Still later they became pulp thrillers, always gory and sensational, frequently plagiaristic and preposterous.[34]

In its "Terms & Themes" summary of captivity narratives, the University of Houston at Clear Lake suggests that:

In American literature, captivity narratives often relate particularly to the capture of European-American settlers or explorers by Native American Indians, but the captivity narrative is so inherently powerful that the story proves highly adaptable to new contents from terrorist kidnappings to UFO abductions.

...

- Anticipates popular fiction, esp. romance narrative: action, blood, suffering, redemption – a page-turner

- Anticipates or prefigures Gothic literature with depictions of Indian "other" as dark, hellish, cunning, unpredictable

...

- Test of ethnic faith or loyalty: Will captive "go native," crossing to the other side, esp. by intermarriage?[35]

The Oxford Companion to United States History indicates that the wave of Catholic immigration after 1820:

provided a large, visible enemy and intensified fears for American institutions and values. These anxieties inspired vicious anti-Catholic propaganda with pornographic overtones, such as Maria Monk's Awful Disclosures[.][36]

Alexandra Heller-Nicholas (quoted earlier) points to the presence of a "helpless" maiden, and a "hero" who rescues her.

Together, these analyses suggest that some of the common elements we may encounter in different types of captivity narratives include:

- A captor portrayed as quintessentially evil

- A suffering victim, often female

- A romantic or sexual encounter occurring in an "alien" culture

- An heroic rescue, often by a male hero

- An element of propaganda

Notable captivity narratives

15th century

- Johann Schiltberger (1460), Reisebuch

16th–17th century

- Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca (1542), La Relacion (The Report); Translated as The Narrative of Cabeza De Vaca by Rolena Adorno and Patrick Charles Pautz.

- Hans Staden (1557), True Story and Description of a Country of Wild, Naked, Grim, Man-eating People in the New World, America

- Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda (1575), Memoir On the Country and Ancient Indian Tribes Of Florida

- Francisco Núñez de Pineda y Bascuñán (1673), Cautiverio feliz y razón individual de las guerras dilatadas del reino de Chile (Happy Captivity and Reason for the Prolonged Wars of the Kingdom of Chile)

- Fernão Mendes Pinto (1614), Pilgrimage

- Anthony Knivet (1625), The Admirable Adventures and Strange Fortunes of Master Antonie Knivet

- Robert Knox (1659–1678), An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon

- Hendrick Hamel (1668), Hamel's Journal and a Description of the Kingdom of Korea, 1653–1666

- Mary Rowlandson (1682), The Sovereignty and Goodness of God

- Cotton Mather (1696–97), The Captivity of Hannah Dustan

18th century

- John Williams (Reverend), The Redeemed Captive (1709)

- Robert Drury, Madagascar, or Robert Drury's Journal (1729)

- John Gyles, Memoirs of odd adventures, strange deliverances, &c. in the captivity of John Gyles, Esq; commander of the garrison on St. George's River (1736)

- Thomas Pellow (1740), The History of the Long Captivity and Adventures of Thomas Pellow

- William Walton, The Captivity of Benjamin Gilbert and His Family, 1780–83

- Mercy Harbison, The Capture and Escape of Mercy Harbison, 1792 (1792)

- Susannah Willard Johnson, A Narrative of the Captivity of Mrs. Johnson, Containing an Account of Her Sufferings During Four Years With the Indians and French (1796)

- Ann Eliza Bleecker, The History of Maria Kittle (1797), novel

- James Smith, An Account of the Remarkable Occurrences ... in the years 1755, '56, '57, '58 & 59 (1799)

19th century

- John R. Jewitt (1803–1805), A Narrative of the Adventures and Sufferings of John R. Jewitt, only survivor of the crew of the ship Boston, during a captivity of nearly three years among the savages of Nootka Sound: with an account of the manners, mode of living, and religious opinions of the natives

- James Riley (1815), Sufferings in Africa

- Robert Adams (1816), The Narrative of Robert Adams

- John Ingles (c. 1824), The Story of Mary Draper Ingles and Son Thomas Ingles

- Mary Jemison (1824), A Narrative of the Life of Mrs. Mary Jemison

- William Lay (1828), A Narrative of the Mutiny, on Board the Ship Globe, of Nantucket, in the Pacific Ocean, Jan. 1824 And the journal of a residence of two years on the Mulgrave Islands; with observations on the manners and customs of the inhabitants

- John Tanner (1830) A Narrative of the captivity and adventures of John Tanner, thirty years of residence among the Indians, prepared for the press by Edwin James.

- Maria Monk (1836), The Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk

- Eliza Fraser (1837), Narrative of the capture, sufferings, and miraculous escape of Mrs. Eliza Fraser

- Rachel Plummer (1838), Rachael Plummer's Narrative of Twenty One Months Servitude as a Prisoner Among the Commanchee Indians

- Sarah Ann Horn (1839) with E. House, A Narrative of the Captivity of Mrs. Horn, and Her Two Children, with Mrs. Harris, by the Camanche Indians

- Matthew Brayton (1860), The Indian Captive A Narrative of the Adventures and Sufferings of Matthew Brayton in His Thirty-Four Years of Captivity Among the Indians of North-Western America

- Herman Lehmann (1927), Nine Years Among the Indians

20th century

- Helena Valero (1965), Yanoama: The Story of Helena Valero, a Girl Kidnapped by Amazonian Indians

- F. Bruce Lamb (1971), Wizard of the Upper Amazon: The Story of Manuel Córdova-Rios

- Michelle Smith and Lawrence Pazder (1980), Michelle Remembers

- Patty Hearst and Alvin Moscow (1982), Patty Hearst – Her Own Story

- Terry Waite (1993), Taken on Trust

Artistic adaptations

In film

- The Searchers (1956), directed by John Ford and starring John Wayne, is a drama about a man's search for his niece who was taken captive by Comanche in the American West. The film was primarily about him and his search, and was influential because of the multiple psychological layers in the character portrayal. The movie is loosely based on the 1836 kidnapping of nine-year-old Cynthia Ann Parker by Comanche warriors.

- A Man Called Horse (1970), directed by Elliot Silverstein and starring Richard Harris, is a drama about a man captured by the Sioux, who is initially enslaved and mocked by being treated as an animal, but comes to respect his captors' culture and gain their respect. It spawned two sequels, The Return of a Man Called Horse (1976) and Triumphs of a Man Called Horse (1983).

- Where The Spirit Lives (1989), written by Keith Leckie, directed by Bruce Pittman, and starring Michelle St. John, is a "reverse" captivity narrative. It tells the story of Ashtecome, a First Nations (Canadian native) girl who is kidnapped and sent to a residential missionary school, where she is abused.

In music

- Cello-rock band Rasputina parodied captivity narratives in their song "My Captivity by Savages", from their album Frustration Plantation (2004).

- Voltaire's song "Cannibal Buffet", from the album Ooky Spooky (2007), is a humorous take on captivity narratives.

In poetry

- Hilary Holladay's book of poems, The Dreams of Mary Rowlandson, recreates Rowlandson's capture by Indians in poetic vignettes.[37]

- W. B. Yeats (1889), "The Stolen Child", in which a human child is "stolen" by faeries and indoctrinated into their alien way of life. The poem may reflect culturally contested values between English Protestants and Irish Celts, and has a somewhat ironical title and tone. The faeries claim (in effect) to be rescuing the child from "a world that's full of weeping."

References

Citations

- Neal Salisbury. "Review of Colin Caolloway, 'North Country Captives: Selected Narratives of Indian Captivities'", American Indian Quarterly, 1994. vol. 18 (1). p. 97

- Joseph Laycock, "Where Do They Get These Ideas? Changing Ideas of Cults in the Mirror of Popular Culture", Journal of the American Academy of Religion, March 2013, Vol. 81, No. 1, pp. 80–106. Note: Laycock refers to an episode of the animated series King of the Hill, in which young women captured by a "cult" and subjected to a low-protein diet are rescued Texas-style: An open air beef barbecue is held outside the "cult" compound. When the women smell the steaks, and are fed bite-sized morsels, they are instantly rescued from their "brainwashed" state, and return to cultural normality. Laycock's work shows how anti-cult captivity narratives – whether real or fictional, dramatic or comedic – remain a staple of modern media.

- Introduction, Women's Indian Captivity Narratives, p. xv (New York: Penguin, 1998)

- Vaughan, Alden T., and Daniel K. Richter. "Crossing the Cultural Divide:Indians and New Englanders, 1605–1763." Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 90 (1980): p. 53; 23–99.

- White, Lonnie J. "White Women Captives of Southern Plains Indians, 1866–1875", Journal of the West 8 (1969): 327–54

- The Cambridge History of English and American Literature. Volume XV. Colonial and Revolutionary Literature, Early National Literature, Part I, Travellers and Explorers, 1583–1763. 11. Jonathan Dickinson.] URL retrieved 24 March 2010

- Gardner, Jared (2000). Master Plots: Race and the Founding of an American Literature, 1787–1845. Baltimore: JHU Press. p. 35. ISBN 0-8018-6538-7.

- Armstrong, Nancy; Leonard Tennenhouse (1992). The Imaginary Puritan:Literature, Intellectual Labor, and the Origins of Personal Life. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 201. ISBN 0-520-07756-3.

- Metcalf, Richard (1998). Lamar, Howard (ed.). The New Encyclopedia of the American West. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300070880.

- Haefeli and Sweeney, p. 273

- Burt, Daniel S. (2004-01-13). The Chronology of American Literature: America's literary achievements from the colonial era to modern times. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-618-16821-7. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- The Journal of Captain William Pote, Jr.

- https://archive.org/details/historyoflifesuf00grac/page/n6/mode/1up

- "Collection de documents inédits sur le Canada et l'Amérique [microforme]".

- John Witherspoon, Journal of John Witherspoon, Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society, Vol 2, pp. 31–62.

- Smethurst, Gamaliel (1774). Ganong, William Francis (ed.). 'A narrative of an extraordinary escape: out of the hands of the Indians, in the Gulph of St. Lawrence. New Brunswick Historical Society.

- A Journal of Lieut. Simon Stevens, from the time of his being taken, near Fort William-Henry, June the 25th 1758. With an account of his escape from Quebec, and his arrival at Louisbourg, on June the 6th, 1759.

- "Captain Robert Stobo (Concluded)", ed. George M. Kahrl, The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography Vol. 49, No. 3 (Jul., 1941), pp. 254–268

- Loescher, Burt Garfield (1969). The History of Rogers' Rangers: The First Green Berets. San Mateo, California. p. 33.

- Tousignant, Pierre; Dionne-Tousignant, Madeleine (1979). "du Calvet, Pierre". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- "Documentary history of the state of Maine ."

- Gardner, Brian (1968). The Quest for Timbuctoo. London: Cassell & Company. p. 27.

- Adams, Charles Hansford (2006). The Narrative of Robert Adams: A Barbary Captive. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. xlv–xlvi. ISBN 978-0-521-60373-7.

- See Bodi, Anna E., "Patty Hearst: A Media Heiress Caught in Media Spectacle" (2013). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 639, for a more comprehensive and nuanced look at the Patty Hearst phenomenon than is found in most individual articles. Bodi repeatedly poses the dialectic between free choice and agency.

- Ruth Hughes on "The Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk," University of Pennsylvania

- Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, Rape-Revenge Films: A Critical Study New York: McFarland, p. 70

- David G. Bromley, "The Social Construction of Contested Exit Roles", in The Politics of Religious Apostasy, p.37

- See J. Gordon Melton, "Brainwashing and Cults: The Rise and Fall of a Theory"

- See Eileen Barker, "The Scientific Study of Religion? You must be joking!" Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion Vol. 34, No. 3 (Sep., 1995), pp. 287–310.

- See Heyrman, Christine Leigh. "Native American Religion in Early America". Divining America, TeacherServe®. National Humanities Center. Accessed Oct-16-2015.

- Janis Johnson, "Deprogram", The Washington Post, May 21, 1977.

- See "Satanic Ritual Abuse" in The Encyclopedia of Cults, Sects, and New Religions edited by James R. Lewis, p.636

- Schwebel, Sara (June 2011). "Rewriting the Captivity Narrative for Contemporary Children: Speare, Bruchac, and the French and Indian War". The New England Quarterly. 84 (2): 318–346. doi:10.1162/TNEQ_a_00091. JSTOR 23054805. S2CID 57570772.

- Minter, David L. "By Dens of Lions: Notes on Stylization in Early Puritan Captivity Narratives" in American Literature, Vol. 45, No. 3 (Nov., 1973), pp. 335–347, Abstract.

- University of Houston at Clear Lake, "Terms & Themes: Captivity Narrative," visited Oct-20-2015.

- "Anti-Catholic Movement" in The Oxford Companion To United States History, p. 40.

- Hilary Holladay, Poetry Foundation, retrieved 30 April 2017

Other sources

- Baepler, Paul, ed. (1999). White Slaves, African Masters: An Anthology of American Barbary Captivity Narratives. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-03403-4.

- Alice Baker. True stories of New England captives carried to Canada during the old French and Indian wars. 1897

- Coleman, Emma Lewis. New England Captives Carried to Canada between 1677 and 1760 during the French and Indian War, 1925.

- Tragedies of the wilderness, or True and authentic narratives of captives ... By Samuel Gardner Drake

- "Women Captives and Indian Captivity Narratives", Women's History – accessed January 6, 2006

- 'Community and Conflict: Captivity Narratives and Cross-Border Contact in the Seventeenth Century – accessed January 6, 2006

- Strong, Pauline Turner (2002) "Transforming Outsiders: Captivity, Adoption, and Slavery Reconsidered", in A Companion to American Indian History, pp. 339–356. Ed. Philip J. Deloria and Neal Salisbury. Malden, Massachusetts and Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell Publishers.

- Turner, Frederick. Beyond Geography: The Western Spirit Against the Wilderness, New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University, first edition 1980, reprint, 1992.

- Journal of John Witherspoon, Annapolis Royal

External links

- Early American Captivity Narratives, Washington State University

- The Narrative of Robert Adams at the Internet Archive