Cardiac rehabilitation

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as "The sum of activity and interventions required to ensure the best possible physical, mental, and social conditions so that patients with chronic or post-acute cardiovascular disease may, by their own efforts, preserve or resume their proper place in society and lead an active life".[1] CR is a comprehensive model of care including established core components, including structured exercise, patient education, psychosocial counselling, risk factor reduction and behaviour modification, with a goal of optimizing patient's quality of life while helping to reduce the risk of future heart problems.[2]

CR is delivered by a multi-disciplinary team, often headed by a physician such as a cardiologist. Nurses support patients in reducing medical risk factors such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol and diabetes. Physiotherapists or other exercise professionals develop an individualized and structured exercise plan, including resistance training. A dietitian helps create a healthy eating plan. A social worker or psychologist may help patients to alleviate stress and address any identified psychological conditions; for tobacco users, they can offer counseling or recommend other proven treatments to support patients in their efforts to quit. Support for return-to-work can also be provided. CR programs are very patient-centered.

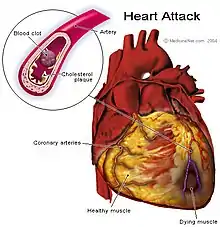

Based on the benefits summarized below, CR programs are recommended by the American Heart Association / American College of Cardiology[3] and the European Society of Cardiology,[4] among other associations.[5] Patients typically enter CR in the weeks following an acute coronary event such as a myocardial infarction (heart attack), with a diagnosis of heart failure, or following percutaneous coronary intervention (such as coronary stent placement), coronary artery bypass surgery, a valve procedure, or insertion of a rhythm device (e.g., pacemaker, implantable cardioverter defibrillator).[6] CR services can be provided in hospital, in an outpatient setting such as a community center, or remotely at home using the phone and other technologies.[2]

CR Phases

Inpatient program (phase I)

Where available, patients receiving CR in the hospital after surgery are usually able to begin within a day or two. First steps include simple motion exercises that can be done sitting down, such as lifting the arms and legs. Heart rate is monitored and continues being monitored as the patient begins to walk.[7]

Outpatient program (phase II)

It is recommended patients begin outpatient CR within 2–7 days following a percutaneous intervention, or 4–6 weeks after cardiac surgery.[8] In order to participate in an outpatient program, the patient generally must first obtain a physician's referral.[9]

Participation typically begins with an intake evaluation that includes measurement of cardiac risk factors such as lipid measures, blood pressure, body composition, depression / anxiety, and tobacco use.[2] An exercise stress test is usually performed both to determine if exercise is safe and to allow for the development of a customized exercise program.[9]

Risk factors are addressed and patients goals are established; a "case-manager" who may be a cardiac-trained Registered Nurse, Physiotherapist, or an exercise physiologist works to help patients achieve their targets. During exercise, the patient's heart rate and blood pressure may be monitored to check the intensity of activity.[9]

The duration of CR varies from program to program, and can range from six weeks to several years. Globally, a median of 24 sessions are offered,[10] and it is well-established that the more the better.[11]

After CR is finished, there are long-term maintenance programs (phase III) available to interested patients,[12] as benefits are optimized with long-term adherence; unfortunately however patients generally have to pay out-of-pocket for these services.

Under-use

CR is significantly under-used globally.[13] Rates vary widely.

Under-use is caused by multi-level factors. At the health system level, this includes lack of available programs.[14] At the provider level, there are low referral rates by physicians,[15] who often focus more attention on better reimbursed cardiac intervention procedures than on long-term lifestyle treatments.[16] At the patient level, factors such as transportation, distance, cost, competing responsibilities, lack of awareness and other health conditions are responsible,[17] but most can be mitigated.[18] Women,[19] ethnocultural minorities,[20] older patients,[21] those of lower socio-economic status, with comorbidities, and living in rural areas[22] are less likely to access CR, despite the fact that these patients often need it most.[23] Cardiac patients can assess their CR barriers here, and receive suggestions on how to overcome them: https://globalcardiacrehab.com/For-Patients.

Strategies are now established on how we can mitigate these barriers to CR use.[24] It is important for inpatient units treating cardiac patients to institute automatic/systematic or electronic referral to CR.[25] It is also key for healthcare providers to promote CR to patients at the bedside.[26]

Benefits

Participation in CR is associated with many benefits. A Cochrane review of 147 studies demonstrated that for myocardial infarction and heart failure patients, CR reduces cardiovascular mortality by 25% and readmission rates by 20%. However, there was no benefit in all-cause mortality.[27][28] A more recent network meta-analysis however, where the complex components of CR are better considered, showed significant reductions in all-cause mortality with CR.[29]

CR is also associated with improved quality of life,[30] as well as better psychosocial well-being, and functional capacity. CR is cost-effective.[31]

There appears to be no difference in outcomes between supervised and home-based CR programs, and both cost about the same.[32]

Another Cochrane review of six randomised controlled trials in adults with atrial fibrillation found that CR may improve physical exercise capacity, but there was no effect on quality of life. Due to the limited number of trials, the authors could not estimate the impact on mortality or serious adverse events.[33] There are also Cochrane reviews on effects in valve patients,[34] among others.

CR Societies

CR professionals work together in many countries to optimize service delivery and increase awareness of CR. The International Council of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (ICCPR), a member of the World Heart Federation, is composed of formally-named Board members of CR societies globally. Through cooperation across most CR-related associations, ICCPR seeks to promote CR in low-resource settings, among other aims outlined in their Charter.[35]

References

- WHO Expert Committee on Rehabilitation after Cardiovascular Diseases, with Special Emphasis on Developing Countries. Rehabilitation after cardiovascular diseases, with special emphsis on developing countries : report of a WHO expert committee. Geneva. ISBN 9241208317. OCLC 28401958.

- Grace SL, Turk-Adawi KI, Contractor A, Atrey A, Campbell N, Derman W, et al. (September 2016). "Cardiac rehabilitation delivery model for low-resource settings". Heart. 102 (18): 1449–55. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2015-309209. PMC 5013107. PMID 27181874.

- Smith SC, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, Braun LT, Creager MA, Franklin BA, et al. (November 2011). "AHA/ACCF Secondary Prevention and Risk Reduction Therapy for Patients with Coronary and other Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation". Circulation. 124 (22): 2458–73. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e318235eb4d. PMID 22052934.

- Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL, et al. (August 2016). "2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR)". European Heart Journal. 37 (29): 2315–2381. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106. PMC 4986030. PMID 27222591.

- Guha S, Sethi R, Ray S, Bahl VK, Shanmugasundaram S, Kerkar P, et al. (April 2017). "Cardiological Society of India: Position statement for the management of ST elevation myocardial infarction in India". Indian Heart Journal. 69 Suppl 1: S63–S97. doi:10.1016/j.ihj.2017.03.006. PMID 28400042.

- Grace SL, Turk-Adawi KI, Contractor A, Atrey A, Campbell NR, Derman W, et al. (2016-11-01). "Cardiac Rehabilitation Delivery Model for Low-Resource Settings: An International Council of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation Consensus Statement". Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. Controversies in Hypertension. 59 (3): 303–322. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2016.08.004. PMID 27542575.

- Zarret BL, Moser M, Cohen LS (1992). "Chapter 28" (PDF). Yale University School of Medicine Heart Book. Yale University School of Medicine. pp. 349–358 [351]. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

Cardiac rehabilitation begins during hospitalization, not after discharge. Today’s heart-attack patient who is free of complications is likely to be up and about in a day or two.

- Dafoe W, Arthur H, Stokes H, Morrin L, Beaton L (September 2006). "Universal access: but when? Treating the right patient at the right time: access to cardiac rehabilitation". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 22 (11): 905–11. doi:10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70309-9. PMC 2570237. PMID 16971975.

- Supervia M, Turk-Adawi K, Lopez-Jimenez F, Pesah E, Ding R, Britto RR, et al. (August 2019). "Nature of Cardiac Rehabilitation Around the Globe". EClinicalMedicine. 13: 46–56. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.06.006. PMID 31517262.

- Chaves G, Turk-Adawi K, Supervia M, Santiago de Araújo Pio C, Abu-Jeish AH, Mamataz T, et al. (January 2020). "Cardiac Rehabilitation Dose Around the World: Variation and Correlates". Circulation. Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 13 (1): e005453. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.005453. PMID 31918580. S2CID 210133397.

- Santiago de Araújo Pio C, Marzolini S, Pakosh M, Grace SL (November 2017). "Effect of Cardiac Rehabilitation Dose on Mortality and Morbidity: A Systematic Review and Meta-regression Analysis". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 92 (11): 1644–1659. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.07.019. hdl:10315/38072. PMID 29101934.

- Mandic S, Body D, Barclay L, Walker R, Nye ER, Grace SL, Williams MJ (July 2015). "Community-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation Maintenance Programs: Use and Effects". Heart, Lung & Circulation. 24 (7): 710–8. doi:10.1016/j.hlc.2015.01.014. PMID 25797326.

- Santiago de Araújo Pio C, Beckie TM, Varnfield M, Sarrafzadegan N, Babu AS, Baidya S, et al. (January 2020). "Promoting patient utilization of outpatient cardiac rehabilitation: A joint International Council and Canadian Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation position statement". International Journal of Cardiology. 298: 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.06.064. PMID 31405584.

- Turk-Adawi K, Supervia M, Lopez-Jimenez F, Pesah E, Ding R, Britto RR, et al. (August 2019). "Cardiac Rehabilitation Availability and Density around the Globe". EClinicalMedicine. 13: 31–45. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.06.007. PMC 6737209. PMID 31517261.

- Ghisi GL, Polyzotis P, Oh P, Pakosh M, Grace SL (June 2013). "Physician factors affecting cardiac rehabilitation referral and patient enrollment: a systematic review". Clinical Cardiology. 36 (6): 323–35. doi:10.1002/clc.22126. PMC 3736151. PMID 23640785.

- Ghanbari-Firoozabadi M, Mirzaei M, Nasiriani K, Hemati M, Entezari J, Vafaeinasab M, Grace SL, Jafary H, Sadrbafghi SM (2020-01-01). "Cardiac Specialists' Perspectives on Barriers to Cardiac Rehabilitation Referral and Participation in a Low-Resource Setting". Rehabilitation Process and Outcome. 9: 1–7. doi:10.1177/1179572720936648.

- Shanmugasegaram S, Gagliese L, Oh P, Stewart DE, Brister SJ, Chan V, Grace SL (February 2012). "Psychometric validation of the cardiac rehabilitation barriers scale". Clinical Rehabilitation. 26 (2): 152–64. doi:10.1177/0269215511410579. PMC 3351783. PMID 21937522.

- Santiago de Araújo Pio C, Chaves GS, Davies P, Taylor RS, Grace SL (February 2019). "Interventions to promote patient utilisation of cardiac rehabilitation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2: CD007131. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007131.pub4. PMC 6360920. PMID 30706942.

- Samayoa L, Grace SL, Gravely S, Scott LB, Marzolini S, Colella TJ (July 2014). "Sex differences in cardiac rehabilitation enrollment: a meta-analysis". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 30 (7): 793–800. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2013.11.007. PMID 24726052.

- Midence L, Mola A, Terzic CM, Thomas RJ, Grace SL (November–December 2014). "Ethnocultural diversity in cardiac rehabilitation". Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention. 34 (6): 437–44. doi:10.1097/HCR.0000000000000089. PMID 25357126.

- Grace SL, Shanmugasegaram S, Gravely-Witte S, Brual J, Suskin N, Stewart DE (2009). "Barriers to cardiac rehabilitation: DOES AGE MAKE A DIFFERENCE?". Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention. 29 (3): 183–7. doi:10.1097/HCR.0b013e3181a3333c. PMC 2928243. PMID 19471138.

- Leung YW, Brual J, Macpherson A, Grace SL (November 2010). "Geographic issues in cardiac rehabilitation utilization: a narrative review". Health & Place. 16 (6): 1196–205. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.08.004. PMC 4474644. PMID 20724208.

- Ruano-Ravina A, Pena-Gil C, Abu-Assi E, Raposeiras S, van 't Hof A, Meindersma E, Bossano Prescott EI, González-Juanatey JR (November 2016). "Participation and adherence to cardiac rehabilitation programs. A systematic review". International Journal of Cardiology. 223: 436–443. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.08.120. PMID 27557484.

- Santiago de Araújo Pio C, Chaves GS, Davies P, Taylor RS, Grace SL (February 2019). "Interventions to promote patient utilisation of cardiac rehabilitation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2: CD007131. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007131.pub4. PMC 6360920. PMID 30706942.

- Grace SL, Russell KL, Reid RD, Oh P, Anand S, Rush J, et al. (February 2011). "Effect of cardiac rehabilitation referral strategies on utilization rates: a prospective, controlled study". Archives of Internal Medicine. 171 (3): 235–41. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.501. PMID 21325114.

- Santiago de Araújo Pio C, Gagliardi A, Suskin N, Ahmad F, Grace SL (August 2020). "Implementing recommendations for inpatient healthcare provider encouragement of cardiac rehabilitation participation: development and evaluation of an online course". BMC Health Services Research. 20 (1): 768. doi:10.1186/s12913-020-05619-2. PMC 7439558. PMID 32819388.

- Anderson L, Taylor RS (December 2014). "Cardiac rehabilitation for people with heart disease: an overview of Cochrane systematic reviews". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD011273. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011273.pub2. hdl:10871/19152. PMC 7087435. PMID 25503364.

- Anderson L, Sharp GA, Norton RJ, Dalal H, Dean SG, Jolly K, et al. (June 2017). "Home-based versus centre-based cardiac rehabilitation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6: CD007130. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007130.pub4. PMC 4160096. PMID 28665511.

- Kabboul NN, Tomlinson G, Francis TA, Grace SL, Chaves G, Rac V, et al. (December 2018). "Comparative Effectiveness of the Core Components of Cardiac Rehabilitation on Mortality and Morbidity: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 7 (12): 514. doi:10.3390/jcm7120514. PMC 6306907. PMID 30518047.

- Francis T, Kabboul N, Rac V, Mitsakakis N, Pechlivanoglou P, Bielecki J, et al. (March 2019). "The Effect of Cardiac Rehabilitation on Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease: A Meta-analysis". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 35 (3): 352–364. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2018.11.013. PMID 30825955.

- Shields GE, Wells A, Doherty P, Heagerty A, Buck D, Davies LM (September 2018). "Cost-effectiveness of cardiac rehabilitation: a systematic review". Heart. 104 (17): 1403–1410. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312809. PMC 6109236. PMID 29654096.

- Anderson L, Sharp GA, Norton RJ, Dalal H, Dean SG, Jolly K, et al. (June 2017). "Home-based versus centre-based cardiac rehabilitation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6): CD007130. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007130.pub4. PMC 6481471. PMID 28665511.

- Risom SS, Zwisler AD, Johansen PP, Sibilitz KL, Lindschou J, Gluud C, et al. (February 2017). "Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for adults with atrial fibrillation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2: CD011197. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011197.pub2. PMC 6464537. PMID 28181684.

- "Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for adults after heart valve surgery". www.cochrane.org. Retrieved 2020-09-23.

- Grace SL, Warburton DR, Stone JA, Sanderson BK, Oldridge N, Jones J, et al. (March–April 2013). "International Charter on Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation: a call for action". Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention. 33 (2): 128–31. doi:10.1097/HCR.0b013e318284ec82. PMC 4559455. PMID 23399847.