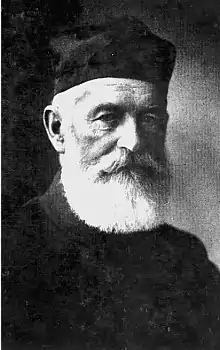

Carl Hugo Hahn

Carl Hugo Hahn (1818–1895) was a Baltic German missionary and linguist who worked in South Africa and South-West Africa for most of his life. Together with Franz Heinrich Kleinschmidt he set up the first Rhenish mission station to the Herero people in Gross Barmen. Hahn is known for his scientific work on the Herero language.

Carl Hugo Hahn | |

|---|---|

Carl Hugo Hahn | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 October 1818 Aahof near Riga, Russian Empire, (Now Latvia) |

| Died | 1895 Cape Town, Cape colony, (Now South Africa) |

| Denomination | Lutheran |

Early life

Hahn was born into a bourgeois family on 18 October 1818 in Aahof near Riga, Latvia. He studied Engineering at the Engineering School of the Russian Army from 1834 onwards but was not satisfied with that choice and, more generally, his parents' way of life. In 1837 he left Ādaži (Aahof) for Barmen (today part of Wuppertal, Germany) to apply at the missionary school of the Rhenish Missionary Society. He was admitted to the Missionary School in Elberfeld (also part of Wuppertal today) in 1838 and graduated in 1841.[1]

Missionary work

Hahn arrived in Cape Town on 13 October 1841. His orders were to bring Christianity to the Nama and the Herero in South-West Africa—not an easy task considering that both tribes were enemies at that time, albeit at peace from Christmas Day 1842 to 1846. He travelled to Windhoek (or as the locals called it then, ǀAiǁgams) in 1842 and was well received by Jonker Afrikaner, Captain of the Orlam Afrikaner tribe residing there. When in 1844 Wesleyan missionaries led by Richard Haddy arrived at the invitation of Jonker Afrikaner, Hahn and his colleague Franz Heinrich Kleinschmidt moved northwards into Damaraland in order to avoid conflict with them.[2]

Hahn and Kleinschmidt arrived at Otjikango on 31 October 1844. They named the place Barmen (today Gross Barmen) after the headquarters of the Rhenish Missionary Society in Germany and established the first Rhenish mission station to the Herero there.[3] Hahn learned the language and taught gardening and animal husbandry, building a church in 1850 and attempting to evangelize. At that time Jonker Afrikaner oversaw the development of the road network in South-West Africa. Hahn and Kleinschmidt initiated the creation of a path from Windhoek to Barmen via Okahandja, and in 1850 this road, later known as Alter Baiweg (Old Bay Path), was extended via Otjimbingwe to Walvis Bay.[4] This route served as an important trade connection between the coast and Windhoek until the end of the century.[5]

Their missionary work was not very successful, and in 1850, after a crushing Herero defeat at the hands of Jonker's Nama troops in Okahandja, the Herero fled the area. Hahn was recalled to Germany to report back, but was given new orders upon arrival in Cape Town in November 1852. Since Haddy had fled Windhoek in the wake of Jonker's raids, Hahn was tasked to fill the void, but he failed and returned to Germany, arriving in Barmen on September 13, 1853.

He traveled Europe between 1853 and 1856 to gather support for his endeavors, which by then were considered futile by the Rhenish Missionary Society. He returned with the order to evangelize the people in Ovamboland, after a brief return to Otjimbingwe where some of the Herero had fled, but his four-month 1857 expedition with the Rev. Johannes Rath to the Ovambo at Ondangwa ended in a disaster, and the members barely escaped alive. Moreover, Gross Barmen was almost destroyed by then due to the skirmishes between Namas and Hereros.[1]

Hahn's next expedition took him, Rath, and Frederick Thomas Green to the banks of the Cunene River. His writing about the journey would later be published in the German travelogue Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen, in which his descriptions of northern Hereroland and the San language, territory, and culture corroborated Francis Galtons reports on Ovamboland. Hahn also included a description of the Etosha pan and collected animal specimens for the Natural History Museum, Berlin. A shortage of missionaries stymied the Rhenish Missionaries in Ovamboland, and Hahn himself returned to Germany in June 1859 to escape the Nama-Herero war, finding friends and support for the Rhenish Missionaries on a whirlwind tour of Germany, England, and Russia.

After the Herero defeated the Nama on many occasions, missionary work was continued. Having turned down an offer to lead the Berlin Missionary Society in 1863, Hahn returned to Otjimbingwe in January 1864 and established a missionary station and a theological seminary there (which he named the Augustineum after St. Augustine of Hippo) to educate indigenous missionaries, this time recruiting German artisans and farmers to supply the settlement. In 1868, however, an attack by the Nama ended his hitherto successful project, and the Herero under chief Maharero fled the settlement to Okahandja and gave up their Christian affiliations. In 1870 Hahn brokered a ten-year peace deal between the Nama and the Herero and convinced the Finnish Missionary Society to take over missionary work in Ovamboland. When the Rhenish Missionary Society began trading for profit and colonizing (rejecting his Lutheran austerity for a more Reformed Church orientation), Hahn severed his ties with them March 4, 1872 and returned in 1873 to Germany, by which time 13 missions in Hereroland were prospering. He relocated to the Cape Colony.[1]

For the next twelve years, Hahn served as pastor of the German Lutheran congregation (St. Martini) in Cape Town. Assisted from 1875 onward by his son (the Rev. C.H. Hahn, Jr.), ministering to a growing population of poorly educated and largely illiterate German settlers in the Cape Flats (arriving largely between 1877 and 1884). During his tenure, he helped found the German International School Cape Town, pay off the debts from the building of St. Martini's church on Long Street, build a parsonage, and spin off daughter churches in Paarl and Worcester. After failed efforts by Cape Colony to make South West Africa a British protectorate, the Nama-Herero war sparked anew on the "bloody night" of August 23, 1880. When, at the end of 1881, a Herero attack was rumored to have occurred on the Cape magistracy in Walvis Bay, Hahn pleaded the Herero's case and urged restraint by colonial authorities in a letter published in the Cape Times on January 13, 1882. From 1882 until his retirement in 1884 he was the Cape Government's "Special Commissioner for the Walwich Bay Territory", traveling there at the behest of Commissioner Hercules Robinson, 1st Baron Rosmead and attempting to restore peace to South West Africa in talks with Maharero in Okahandja (February 17–18, 1882).[6] Apart from a treaty between the Swartbooi Nama and the Herero, Hahn was unsuccessful and recommended in his March 1882 report to the Cape government that the Walvis Bay area be maintained as British territory.

Linguistic works

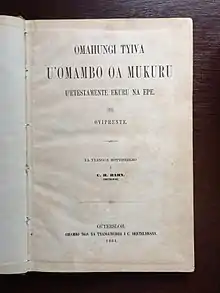

While in Gross Barmen, Hahn learned to speak Otjiherero (first gaining the ability to preach in the language on January 29, 1847) and translated the New Testament and other religious texts into the language of the natives. As early as 1846, he compiled the first Rhenish Missionary prayer book in Herero, and together with Rath, he released a collection of biblical stories and hymns translated into the language under the title Ornahungi oa embo ra Jehova in 1849. Additional prayer books in 1861 and 1871 book-ended his 1864 output of two further biblical narratives, a copy of Luther's Small Catechism, and a 32-song hymnal. Highlights of the Old Testament and the aforementioned complete NT began the work that Peter Heinrich Brincker and others would complete.

Hahn also drafted W.H.I. Bleek's unpublished grammar of Otjiherero (Entwurf einer Grammatik der Herero Sprache, 1854) , ultimately delivering his own version to Riga in December 1854, and published its first dictionary, Grundzüge einer Grammatik des Herero (im Westlichen Afrika) nebst einem Wörterbuche (Berlin/London, 1857) through the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences. The latter, including a comprehensive grammar and a Herero-German dictionary of 4,300 words, was the first publication using Standard Alphabet by Richard Lepsius, eventually causing much consternation over its suitability for transcribing a Bantu language. During his visit to Germany in 1873/74, University of Leipzig awarded a Doctor degree honoris causa to Hahn for his research on the language of the Herero,[1] although his domestic servant and interpreter, Urieta (Johanna Gertze) probably had a more than cursory role in the creation of his language studies and publications.[7]

Family life

Carl Hugo Hahn married his wife Emma (née Hone, daughter of William Hone) on 3 October 1843, on home leave in Cape Town. They had at least five children, including two daughters (Margaritha, wife of Carl Heinrich Beiderbecke since their marriage on November 24, 1875; and Eloisa) and three sons (including William Heinrich Josaphat, Carl Hugo Jr., and Traugott). While Carl Sr. ministered in South-West Africa, his children attended school in Gütersloh. Emma died on April 14, 1880 in Cape Town, after which he visited Germany for a short while. After his retirement for health reasons in 1884, Hahn visited Margaritha in the United States, and later lived with his son, Carl Jr. in Paarl, then minister of St. Petri's Lutheran Church there. Traugott worked in the Lutheran Church in Livonia, and several of his descendants became theologians and clerics in Germany. Carl Hugo Hahn, Sr., died in Cape Town on 24 November 1895 and is buried at St. Petri in Paarl.[6]

Works

- Hahn, Carl Hugo (1857). Grundzüge der Grammatik des Herero nebst einem Wörterbuch [Basics of the Herero Grammar, also a Dictionary] (in German). Berlin: National Academy.

- Hahn, Carl Hugo (1984). Tagebücher 1837–1860 [Diaries 1837–1860] (in German). Windhoek: B.Lau.

References

Footnotes

- Wolf-Dahm, Barbara. "Hahn, Carl. Afrikamissionar und Sprachforscher" [Hahn, Carl. Missionary to Africa and Linguist] (in German). Kulturstiftung der deutschen Vertriebenen, Ostdeutsche Biographie [Cultural Foundation of German Refugees, East–German Biography]. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- Vedder 1997, p. 222.

- "Gross Barmen Namibia Hot Springs". Namibia 1-on-1. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- Vedder 1997, pp. 252–253.

- Henckert, Wolfgang (16 March 2006). "Karibib". Henckert Tourist Centre. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011.

- Dierks, Klaus. "Biographies of Namibian Personalities". www.klausdierks.com. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- Shiremo, Shampapi (28 January 2011). "Johanna Uerieta Gertze: The dedicated pioneer Christian and teacher (1840–1936)". New Era. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

Literature

- De Kock, W.J. (1968). Suid-Afrikaanse Biografiese Woordeboek, vol. 1. Pretoria: Nasionale Raad vir Sosiale Navorsing, Departement van Hoër Onderwys.</ref>

- Vedder, Heinrich (1997). Das alte Südwestafrika. Südwestafrikas Geschichte bis zum Tode Mahareros 1890 [The old South-West Africa. South-West Africa's history until Maharero's death 1890] (in German) (7th ed.). Windhoek: Namibia Scientific Society. ISBN 0-949995-33-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)