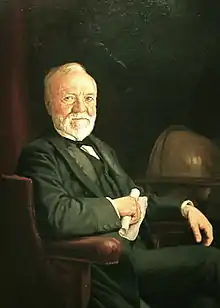

Carnegie library

A Carnegie library is a library built with money donated by Scottish-American businessman and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. A total of 2,509 Carnegie libraries were built between 1883 and 1929, including some belonging to public and university library systems. 1,689 were built in the United States, 660 in the United Kingdom and Ireland, 125 in Canada, and others in Australia, South Africa, New Zealand, Serbia, Belgium, France, the Caribbean, Mauritius, Malaysia, and Fiji.

At first, Carnegie libraries were almost exclusively in places with which he had a personal connection—namely his birthplace in Scotland and the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania area, his adopted home-town. Yet, beginning in the middle of 1899, Carnegie substantially increased funding to libraries outside these areas.

In later years few towns that requested a grant and agreed to his terms, of committing to operation and maintenance, were refused. By the time the last grant was made in 1919, there were 3,500 libraries in the United States, nearly half of them known as Carnegie libraries, as they were built with construction grants paid by Carnegie.

History

Carnegie started erecting libraries in places with which he had personal associations.[1] The first of Carnegie's public libraries, Dunfermline Carnegie Library was in his birthplace, Dunfermline, Scotland. It was first commissioned or granted by Carnegie in 1880 to James Campbell Walker[2] and would open in 1883.

The first library in the United States to be commissioned by Carnegie was in 1886 in his adopted hometown of Allegheny, Pennsylvania, (now the North Side of Pittsburgh). In 1890, it became the second of his libraries to open in the US. The building also contained the first Carnegie Music Hall in the world.

The first Carnegie library to open in the United States was in Braddock, Pennsylvania, about 9 miles up the Monongahela river from Pittsburgh. In 1889 it was also the site of one of the Carnegie Steel Company's mills. It was the second Carnegie Library in the United States to be commissioned, in 1887, and was the first of the four libraries which he fully endowed. An 1893 addition doubled the size of the building and included the third Carnegie Music Hall in the United States.

Initially Carnegie limited his support to a few towns in which he had a personal interest. These were in Scotland and the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania area. In the United States, nine of the first 13 libraries which he commissioned are all located in Southwestern Pennsylvania. The Braddock, Homestead, and Duquesne libraries were owned not by municipalities, but by Carnegie Steel, which constructed them, maintained them, and delivered coal for their heating systems.[3] Architectural critic Patricia Lowry wrote "to this day, Carnegie's free-to-the-people libraries remain Pittsburgh's most significant cultural export, a gift that has shaped the minds and lives of millions."[4]

In 1897, Carnegie hired James Bertram as his personal assistant. Bertram was responsible for fielding requests from municipalities for funds and overseeing the dispensing of grants for libraries. When Bertram received a letter requesting a library, he sent the applicant a questionnaire inquiring about the town's population, whether it had any other libraries, how large its book collection was, and what its circulation figures were. If initial requirements were met, Bertram asked the amount the town was willing to pledge for the library's annual maintenance, whether a site was being provided, and the amount of money already available.[5]

Until 1898, only one library was commissioned in the United States outside Southwestern Pennsylvania: a library in Fairfield, Iowa, commissioned in 1892. It was the first project in which Carnegie had funded a library to which he had no personal ties. The Fairfield project was part of a new funding model to be used by Carnegie (through Bertram) for thousands of additional libraries.[6]

Beginning in 1899, Carnegie's foundation funded a dramatic increase in the number of libraries. This coincided with the rise of women's clubs in the post-Civil War period. They primarily took the lead in organizing local efforts to establish libraries, including long-term fundraising and lobbying within their communities to support operations and collections.[7] They led the establishment of 75–80 percent of the libraries in communities across the country.[8]

Carnegie believed in giving to the "industrious and ambitious; not those who need everything done for them, but those who, being most anxious and able to help themselves, deserve and will be benefited by help from others."[9] Under segregation black people were generally denied access to public libraries in the Southern United States. Rather than insisting on his libraries being racially integrated, Carnegie funded separate libraries for African Americans in the South. For example, in Houston he funded a separate Colored Carnegie Library.[10] The Carnegie Library in Savannah, Georgia, opened in 1914 to serve black residents, who had been excluded from the segregated white public library. The privately organized Colored Library Association of Savannah had raised money and collected books to establish a small Library for Colored Citizens. Having demonstrated their willingness to support a library, the group petitioned for and received funds from Carnegie.[11] U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas wrote in his 2008 memoirs that he frequently used that library as a boy, before the public library system was desegregated.[12]

The library buildings were constructed in a number of styles, including Beaux-Arts, Italian Renaissance, Baroque, Classical Revival, and Spanish Colonial, to enhance their appearance as public buildings. Scottish Baronial was one of the styles used for libraries in Carnegie's native Scotland. Each style was chosen by the community. As the years went by James Bertram, Carnegie's secretary, became less tolerant of approving designs that were not to his taste.[13] Edward Lippincott Tilton, a friend often recommended by Bertram, designed many of the buildings.[14]

The architecture was typically simple and formal, welcoming patrons to enter through a prominent doorway, nearly always accessed via a staircase from the ground level. The entry staircase symbolized a person's elevation by learning. Similarly, most libraries had a lamppost or lantern installed near the entrance, meant as a symbol of enlightenment.

Carnegie's grants were very large for the era, and his library philanthropy is one of the most costly philanthropic activities, by value, in history. Carnegie continued funding new libraries until shortly before his death in 1919. Libraries were given to Great Britain and much of the English-speaking world: Almost $56.2 million went for construction of 2,509 libraries worldwide. Of that, $40 million was given for construction of 1,670 public library buildings in 1,412 American communities.[15] Small towns received grants of $10,000 that enabled them to build large libraries that immediately were among the most significant town amenities in hundreds of communities.[16]

Background

Books and libraries were important to Carnegie, from his early childhood in Scotland and his teen years in Allegheny/Pittsburgh. There he listened to readings and discussions of books from the Tradesman's Subscription Library, which his father had helped create.[17] Later in Pennsylvania, while working for the local telegraph company in Pittsburgh, Carnegie borrowed books from the personal library of Colonel James Anderson. He opened his collection to his workers every Saturday. Anderson, like Carnegie, resided in Allegheny.

In his autobiography, Carnegie credited Anderson with providing an opportunity for "working boys" (that some people said should not be "entitled to books") to acquire the knowledge to improve themselves.[18] Carnegie's personal experience as an immigrant, who with help from others worked his way and became wealthy, reinforced his belief in a society based on merit, where anyone who worked hard could become successful. This conviction was a major element of his philosophy of giving in general.[19] His libraries were the best-known expression of this philanthropic goal.

Carnegie formula

Nearly all of Carnegie's libraries were built according to "the Carnegie formula," which required financial commitments for maintenance and operation from the town that received the donation. Carnegie required public support rather than making endowments because, as he wrote:

- "an endowed institution is liable to become the prey of a clique. The public ceases to take interest in it, or, rather, never acquires interest in it. The rule has been violated which requires the recipients to help themselves. Everything has been done for the community instead of its being only helped to help itself."[20]

Carnegie required the elected officials—the local government—to:

- demonstrate the need for a public library;

- provide the building site;

- pay staff and maintain the library;

- draw from public funds to run the library—not use only private donations;

- annually provide ten percent of the cost of the library's construction to support its operation; and,

- provide free service to all.

Carnegie assigned the decisions to his assistant James Bertram. He created a "Schedule of Questions." The schedule included: Name, status and population of town, Does it have a library? Where is it located and is it public or private? How many books? Is a town-owned site available? Estimation of the community's population at this stage was done by local officials, and Bertram later commented that if the population counts he received were accurate, "the nation's population had mysteriously doubled".[21]

The effects of Carnegie's library philanthropy coincided with a peak in new town development and library expansion in the US.[22] By 1890, many states had begun to take an active role in organizing public libraries, and the new buildings filled a tremendous need. It was also a time of rapid development of institutions of higher learning. Interest in libraries was also heightened at a crucial time in their early development by Carnegie's high profile and his genuine belief in their importance.[23]

In Canada in 1901, Carnegie offered more than $2.5 million to build 125 libraries. Most cities at first turned him down—then relented and took the money.[24]

In 1902, Carnegie offered funds to build a library in Dunedin in New Zealand. Between 1908 and 1916, 18 Carnegie libraries were opened across New Zealand.[25]

Design

The Lawrenceville Branch of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh signaled a break from the Richardsonian style of libraries which was popularized in the mid 1800s. The ALA discouraged Richardsonian characteristics such as alcoved book halls with high shelves requiring a ladder, as well as sheltered galleries and niches, reminiscent of sixteenth-century Europe, largely because modern librarians could not supervise such spaces efficiently.[26]

Bertram's architectural criteria included a lecture room, reading rooms for adults and children, a staff room, a centrally located librarian's desk, twelve-to-fifteen-foot ceilings, and large windows six to seven feet above the floor. No architectural style was recommended for the exterior, nor was it necessary to put Andrew Carnegie's name on the building. In the interests of efficiency, fireplaces were discouraged, since that wall space could be used to house more books.[27]

There were no strict requirements about furniture, but most of it came from the Library Bureau, established by Melvil Dewey in 1888. It sold standardized chairs, tables, catalogs, and bookshelves.[28]

Self-service stacks

The first five Carnegie libraries followed a closed stacks policy, the method of operation common to libraries at that time. Patrons requested a book from a library staffer, who would fetch the book from closed stacks off limits to the public, and bring it to a delivery desk.

To reduce operating costs, Carnegie created a revolutionary open-shelf or self-service policy, beginning with the Pittsburgh neighborhood branches that opened after the main branch. This streamlined process allowed patrons to have open access to shelves. Carnegie's architects designed the Pittsburgh neighborhood branches so that one librarian could oversee each entire operation.

Theft of books and other items was a major concern. This concern resulted in the placement of the library's circulation desk—which replaced the delivery desk used in traditional closed stacks libraries— in a strategic position just inside the front door. Bigger and more daunting than those used in modern libraries, these desks spanned almost the width of the lobby and acted as a physical and psychological barrier between the front entrance and the book room. Decades later, Joyce Broadus, the manager of Pittsburgh's Homewood branch, was credited with dubbing this design of the front desk "the battleship."

The first of these 'open stack' branches was in the neighborhood of Lawrenceville, the sixth Carnegie library to open in America. The next was in the West End branch, the eighth Carnegie library in the US. Patricia Lowry describes

located just beyond the lobby, the circulation desk—no longer a delivery desk—took center stage in Lawrenceville, flanked by turnstiles that admitted readers to the open stacks one at a time, under the librarian's watchful eye. To thwart thievery, the stacks were arranged in a radial pattern. On each side of the lobby were a general reading room and, for the first time in a library anywhere, a room for children.... The reading rooms were separated by walls that became glass partitions above waist level—the better to see you with, my dear.[4]

Walter E. Langsam, an architectural historian and teacher at the University of Cincinnati, wrote "The Carnegie libraries were important because they had open stacks which encouraged people to browse .... People could choose for themselves what books they wanted to read."[29] This open stacks policy was later adopted by the libraries that previously had operated with closed stacks.

Continuing legacy

Carnegie established charitable trusts which have continued his philanthropic work. But they had reduced their investment in libraries even before his death. There has continued to be support for library projects, for example in South Africa.[30]

In 1992, The New York Times reported that, according to a survey conducted by George Bobinksi, dean of the School of Information and Library Studies at the State University at Buffalo, 1,554 of the 1,681 original Carnegie library buildings in the United States still existed, and 911 were still used as libraries. He found that 276 were unchanged, 286 had been expanded, 175 had been remodeled, 243 had been demolished, and others had been converted to other uses.[31]

While hundreds of the library buildings have been adapted for use as museums, community centers, office buildings, residences, or other uses, more than half of those in the United States still serve their communities as libraries over a century after their construction.[32] Many are located in what are now middle- to low-income neighborhoods. For example, Carnegie libraries still form the nucleus of the New York Public Library system in New York City, with 31 of the original 39 buildings still in operation. Also, the main library and eighteen branches of the Pittsburgh public library system are Carnegie libraries. The public library system there is named the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh.[33]

In the late 1940s, the Carnegie Corporation of New York arranged for microfilming of the correspondence files relating to Andrew Carnegie's gifts and grants to communities for the public libraries and church organs. They discarded the original materials. The microfilms are open for research as part of the Carnegie Corporation of New York Records collection, residing at Columbia University Rare Book and Manuscript Library.[34] Archivists did not microfilm photographs and blueprints of the Carnegie Libraries. The number and nature of documents within the correspondence files varies widely. Such documents may include correspondence, completed applications and questionnaires, newspaper clippings, illustrations, and building dedication programs.

UK correspondence files relating to individual libraries have been preserved in Edinburgh (see the article List of Carnegie libraries in Europe).

Beginning in the 1930s during the Great Depression, some libraries were meticulously measured, documented and photographed under the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) program of the National Park Service. This was part of an effort to record and preserve significant buildings..[35] Other documentation has been collected by local historical societies. In 1935, the centennial of Carnegie's birth, a copy of the portrait of him originally painted by F. Luis Mora was given to libraries which he had helped fund.[36] Many of the Carnegie libraries in the United States, whatever their current uses, have been recognized by listing on the National Register of Historic Places. The first, the Carnegie Library in Braddock, Pennsylvania, was designated as a National Historic Landmark in March 2012. Some Carnegie Libraries, have been replaced in name with that of city libraries such as the Epiphany library in New York City.

Gallery

Edinburgh Central Library, built in 1890 in Edinburgh, Scotland

Edinburgh Central Library, built in 1890 in Edinburgh, Scotland.jpg.webp) Carnegie Library, built in 1904 in Akron, Ohio

Carnegie Library, built in 1904 in Akron, Ohio

Carnegie Library, built in 1901 in Guthrie, Oklahoma

Carnegie Library, built in 1901 in Guthrie, Oklahoma West Tampa Free Public Library, built in 1914 in Tampa, Florida

West Tampa Free Public Library, built in 1914 in Tampa, Florida St. Petersburg Public Library, built in 1915 in St. Petersburg, Florida

St. Petersburg Public Library, built in 1915 in St. Petersburg, Florida Beaumont Library built in 1914 in Beaumont, California

Beaumont Library built in 1914 in Beaumont, California Carnegie Public Library, built in 1904 in Tyler, Texas

Carnegie Public Library, built in 1904 in Tyler, Texas Carnegie Library, built in 1908 in Hokitika, New Zealand

Carnegie Library, built in 1908 in Hokitika, New Zealand

Lists of Carnegie libraries

- List of Carnegie libraries in Africa, the Caribbean and Oceania

- List of Carnegie libraries in Canada

- List of Carnegie libraries in Europe

- List of Carnegie libraries in the United States

See also

Notes

- Gangewere, Robert (2011). Palace of culture: Andrew Carnegie's museums and library in Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh, Pa: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- "James Campbell Walker". Dictionary of Scottish Architects. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- Gangewere, Robert (2011). Palace of culture: Andrew Carnegie's museums and library in Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh, Pa: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- "Carnegie's Library Legacy". Archived from the original on May 9, 2016.

- Gangewere, Robert (2011). Palace of culture: Andrew Carnegie's museums and library in Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh, Pa: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- "Carnegie Historical Museum – Fairfield Cultural District". fairfieldculturaldistrict.org. Archived from the original on April 6, 2014. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- Paula D. Watson, "Founding Mothers: The Contribution of Women's Organizations to Public Library Development in the United States", Library Quarterly, Vol. 64, Issue 3, 1994, p.236

- Teva Scheer, "The "Praxis" Side of the Equation: Club Women and American Public Administration", Administrative Theory & Praxis, Vol. 24, Issue 3, 2002, p. 525

- Andrew Carnegie, "The Best Fields for Philanthropy" Archived January 13, 2003, at the Wayback Machine, The North American Review, Volume 149, Issue 397, December 1889 from the Cornell University Library website

- This library has been discussed in Cheryl Knott Malone's essay, "Houston's Colored Carnegie Library, 1907–1922." While still in manuscript, it was awarded the Justin Winsor Prize in 1997. Accessed on-line August 2008 in a revised version Archived September 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Live Oak Public Libraries: Library History, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved August 18, 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) (main page) "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 20, 2015. Retrieved August 18, 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) (details), accessed August 17, 2014.

- Clarence Thomas, My Grandfather's Son: A Memoir, HarperCollins, 2008, pp. 17, 29, 30, Google Books

- "Carnegie Libraries – Reading 2". Archived from the original on May 2, 2014.

- Mausolf, Lisa B.; Hengen, Elizabeth Durfee (2007), Edward Lippincott Tilton: A Monograph on His Architectural Practice (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2011, retrieved September 28, 2011,

Many of these were Carnegie Libraries, public libraries built between 1886 and 1917 with funds provided by Andrew Carnegie or the Carnegie Corporation of New York. In all, Carnegie funding was provided for 1,681 public library buildings in 1,412 U.S. communities, with additional libraries abroad. Increasingly after 1908, Carnegie library commissions tended to be in the hands of a relatively small number of firms that specialized in library design. Tilton benefited from a friendship with James Bertram, who was responsible for reviewing plans for Carnegie-financed library buildings. Although the Carnegie program left the hiring of an architect to local officials, Bertram's personal letters of introduction gave Tilton a distinct advantage. As a result, Tilton won a large number of comparatively modest Carnegie library commissions, primarily in the northeast. Typically, Tilton furnished all plans, working drawings, details and specifications and associated with a local architect, who would supervise construction and receive 5% of Tilton's commission.

- Murray, Stuart (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History. New York: Skyhorse Chicago: ALA Editions. pp. 174–91.

- M.J. Kevane and W.A. Sundstrom, "Public libraries and political participation, 1870–1940," Santa Clara University Scholar Commons (2016)online Archived December 20, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Murray, Stuart (2009). The library : an illustrated history. New York: Skyhorse Pub. ISBN 978-1-60239-706-4.

- "Andrew Carnegie: A Tribute: Colonel James Anderson" Archived February 11, 2004, at the Wayback Machine, Exhibit, Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

- Murray, Stuart (2009). The library : an illustrated history. New York: Skyhorse Pub. ISBN 978-0838909911. OCLC 277203534.

- Carnegie, Andrew (December 1889). "The Best Fields for Philanthropy". North American Review. 149: 688–691.

- Gigler, Rich (July 17, 1983). "Thanks, but no thanks". The Pittsburgh Press. p. 12. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- Kevane, Michael; Sundstrom, William A. (April 30, 2014). "The Development of Public Libraries in the United States, 1870–1930: A Quantitative Assessment". Information & Culture: A Journal of History. 49 (2): 117–144. doi:10.1353/lac.2014.0009. ISSN 2166-3033. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017.

- Bobinski, p. 191

- Susan Goldenberg, "Dubious Donations," Beaver (2008) 88#2

- Te Ara, The Encyclopedia of New Zealand (October 22, 2014). "Carnegie libraries in New Zealand". teara.govt.nz. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- Gangewere, Robert (2011). Palace of culture: Andrew Carnegie's museums and library in Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh, Pa: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Gangewere, Robert (2011). Palace of culture: Andrew Carnegie's museums and library in Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh, Pa: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Gangewere, Robert (2011). Palace of culture: Andrew Carnegie's museums and library in Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh, Pa: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Al Andry, "New Life for Historic Libraries" Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, The Cincinnati Post, October 11, 1999

- The Carnegie Corporation and South Africa: Non-European Library Services Archived August 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Libraries & Culture, Volume 34, No. 1 Archived June 12, 2010, at the Wayback Machine (Winter 1999), from the University of Texas at Austin

- Strum, Charles (March 2, 1992), "Belleville Journal; Restoring Heritage and Raising Hopes for Future", The New York Times, archived from the original on November 14, 2013, retrieved September 29, 2011,

Dr. George Bobinksi, dean of the School of Information and Library Studies at the State University at Buffalo, says 1,681 libraries were built with Carnegie money, mostly between 1898 and 1917.In a survey, he found that at least 1,554 of the buildings still exist, with only 911 of these still in use as public libraries. At least 276 of the survivors are unchanged, while 243 have been demolished, 286 have been expanded and 175 have been remodeled. Others have been turned into condominiums, community centers or shops.

- "Carnegie libraries by state" (PDF). American Volksporting Association. 1996. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 14, 2012. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- "Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh". Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh. Archived from the original on January 2, 2018. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- "Rare Book & Manuscript Library". Archived from the original on January 14, 2009.

- Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record (HABS/HAER) Archived May 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Permanent Collection, American Memory from the Library of Congress

- "Belmar Public Library". Wall, New Jersey. American towns. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

Further reading

- Anderson, Florence. Carnegie Corporation Library Program, 1911–1961... (Carnegie Corporation of New York, 1963)

- Bobinski, George S. "Carnegie libraries: Their history and impact on American public library development." ALA Bulletin (1968): 1361–1367. in JSTOR

- Ditzion, Sidney. Arsenals of a Democratic Culture (American Library Association, 1947).

- Fultz, Michael. "Black Public Libraries in the South in the Era of De Jure Segregation" Libraries & the Cultural Record (2006). 41(3), 337–359.

- Garrison, Dee. Apostles of culture : the public librarian and American society, 1876–1920 (New York: Free Press, 1979).

- Grimes, Brendan. (1998). Irish Carnegie Libraries: A catalogue and architectural history, Irish Academic Press. ISBN 0-7165-2618-2

- Harris, Michael. (1974). "The Purpose of the American Public Library, A Revisionist Interpretation of History" Library Journal 98:2509–2514.

- Jones, Theodore. (1997). Carnegie Libraries Across America: A Public Legacy, John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-14422-3

- Kevane, M.J. and W.A. Sundstrom, "Public libraries and political participation, 1870–1940" Santa Clara University Scholar Commons (2016)online; uses advanced statistics to find a new library had no effect on voter turnout

- Kevane, Michael, & Sundstrom, William A. (2014). "The Development of Public Libraries in the United States, 1870–1930: A Quantitative Assessment" Information and Culture, 49#2, 117–144.

- Lorenzen, Michael. (1999). "Deconstructing the Carnegie Libraries: The Sociological Reasons Behind Carnegie's Millions to Public Libraries", Illinois Libraries. 81, no. 2: 75–78.

- Martin, Robert Sidney. Carnegie denied: communities rejecting Carnegie Library construction grants, 1898–1925 (Greenwood Press, 1993)

- Miner, Curtis. "The'Deserted Parthenon': Class, Culture and the Carnegie Library of Homestead, 1898–1937." Pennsylvania History (1990): 107–135. in JSTOR

- Nasaw, David. Andrew Carnegie. New York: Penguin Press, 2006.

- Pollak, Oliver B. A State of Readers, Nebraska's Carnegie Libraries, (Lincoln: J. & L. Lee Publishers, 2005).

- Prizeman, Oriel. Philanthropy and light: Carnegie libraries and the advent of transatlantic standards for public space (Ashgate, 2013).

- Swetman, Susan H. (1991). "Pro-Carnegie library arguments and contemporary concerns in the intermountain west." Journal of the West 30#3, 63–68.

- Watson, Paula. (1996). "Carnegie Ladies, Lady Carnegies : Women and the Building of Libraries." Libraries & Culture 31#1, 159–196.

- Watson, Paula D. (1994). "Founding mothers: the contribution of women's organizations to public library development in the United States" Library Quarterly 64(3), 233–270.

- Wiegand, Wayne A. (2011). Main Street Public Library: Community Places and Reading Spaces in the Rural Heartland, 1876–1956 (University of Iowa Press).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carnegie libraries. |

| Look up Carnegie library in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Skeen, Molly. (March 5, 2004) "How America's Carnegie Libraries Adapt to Survive", Preservation Online.