Cartoonist

A cartoonist (also comic strip creator, comic book artist, graphic novel artist,[1] or comic book illustrator) is a visual artist who specializes in drawing cartoons (individual images) or comics (sequential images). Cartoonists include the artists who handle all aspects of the work and those who contribute only part of the production. Cartoonists may work in many formats, such as booklets, comic strips, comic books, editorial cartoons, graphic novels, manuals, gag cartoons, illustrations, storyboards, posters, shirts, books, advertisements, greeting cards, magazines, newspapers, and video game packaging.

|

| Comics |

|---|

| Comics studies |

| Methods |

| Media Formats |

| Comics by Country and Culture |

| Community |

|

|

History

In the West

The English satirist and editorial cartoonist William Hogarth, who emerged In the 18th century, has poked fun at contemporary politics and customs; illustrations in such style are often referred to as "Hogarthian".[2] Following the work of Hogarth, political cartoons began to develop in England in the latter part of the 18th century under the direction of its great exponents, James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson, both from London. Gillray explored the use of the medium for lampooning and caricature, calling the king (George III), prime ministers and generals to account, and has been referred to as the father of the political cartoon.[3]

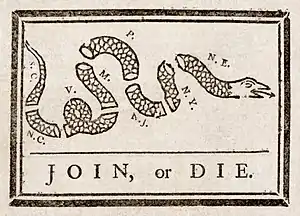

While never a professional cartoonist, Benjamin Franklin is credited with having the first cartoon published in an American newspaper.[4] In the 19th century, professional cartoonists such as Thomas Nast introduced other familiar American political symbols, such as the Republican elephant.[4]

During the 20th century, numerous magazines carried single-panel gag cartoons by such freelance cartoonists as Charles Addams, Irwin Caplan, Chon Day, Clyde Lamb, and John Norment. These were almost always published in black and white, although Collier's often carried cartoons in color. The debut of Playboy introduced full-page color cartoons by Jack Cole, Eldon Dedini, Roy Raymonde and others. Single-panel cartoonists syndicated to newspapers included Dave Breger, Hank Ketcham, George Lichty, Fred Neher, Irving Phillips, and J. R. Williams.

Comic strips

Comic strips received widespread distribution to mainstream newspapers by syndicates,[5] including the Universal Press Syndicate, United Media, or King Features. Sunday strips go to a coloring company such as American Color before they are published. Some comic strip creators publish in the alternative press or on the Internet. Both vintage and current strips receive reprints in book collections.

Calum MacKenzie, in his preface to the exhibition catalog, The Scottish Cartoonists (Glasgow Print Studio Gallery, 1979) defined the selection criteria:

- The difference between a cartoonist and an illustrator was the same as the difference between a comedian and a comedy actor—the former both deliver their own lines and take full responsibility for them, the latter could always hide behind the fact that it was not his entire creation.[6]

Within the comic strip format, it is typical for one creator to produce the whole strip. However, it is also not uncommon for the writing of the strip and the drawing of the art to be carried out by two different people, a writer and an artist (with or without additional assistant artists). In some cases, one artist might draw key figures while another does only backgrounds.

Many strips were the work of two people although only one signature was displayed. Shortly after Frank Willard began Moon Mullins in 1923, he hired Ferd Johnson as his assistant. For decades, Johnson received no credit. Willard and Johnson traveled about Florida, Maine, Los Angeles, and Mexico, drawing the strip while living in hotels, apartments and farmhouses. At its peak of popularity during the 1940s and 1950s, the strip ran in 350 newspapers. According to Johnson, he had been doing the strip solo for at least a decade before Willard's death in 1958: "They put my name on it then. I had been doing it about 10 years before that because Willard had heart attacks and strokes and all that stuff. The minute my name went on that thing and his name went off, 25 papers dropped the strip. That shows you that, although I had been doing it ten years, the name means a lot."[7]

Comic books

There are many books of cartoons in both paperback and hardcover, such as the collections of cartoons from The New Yorker. Prior to the 1960s, cartoons were mostly ignored by museums and art galleries. In 1968, the cartoonist and comedian Roger Price opened the first New York City gallery devoted exclusively to cartoons, mainly work by the leading magazine gag cartoonists. Today, there are several museums devoted to cartoons, notably the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum, run by curator Jenny E. Robb at Ohio State University.

With regards to the comic book format, the work can be split in many different ways. The writing and the creation of the art can be split between two people, an example being From Hell, which was written by Alan Moore and drawn by Eddie Campbell. The writing of a comic book story can sometimes be shared between two people, with one person writing the plot and another the script.

The artistic work is often subdivided, especially on work produced for the larger comic book publishers, with four people typically working on the art: a penciller, an inker, a colorist, and a letterer. Sometimes this combination of four artists is augmented by a fifth, a breakdown artist. However, this generally occurs only when an artist fails to meet a deadline or when a writer, sometimes referred to as a scripter, produces breakdown art. Breakdown art is where the story has been laid out very roughly in pencils to indicate panel layouts and character positions within panels but with no details. Such roughs are sometimes referred to as "layouts."

The norm of four artists is sometimes reduced to three if the penciller also inks his own work, usually being credited within the book as a penciller/inker. John Byrne and Walt Simonson are artists who have, on occasion, inked their own work.

These roles are highly interchangeable, and many artists can fulfill different roles. Stan Sakai is a highly regarded letterer of comic books who also creates his own series, Usagi Yojimbo. Producing his autobiographical works, Eddie Campbell has created both scripts and art, plus teaming with his daughter on the coloring. On Cerebus, for the majority of the run, Dave Sim created everything except the backgrounds, which were drawn by Gerhard.

Web cartoonist

Many artists have used the web since its inception to publish their works online. This eventually led to the creation of webcomics thanks in part to many titles being able to be read for free and anyone being able to publish them. Many of the artists who create these webcomics are known as web cartoonists due to the fact that the vast majority of webcomics are considered to be online versions of comic-strips and cartoons rather than full-fledged comic books like digital comics. It is hard to pinpoint when the actual term was created but the earliest use was 2001 with the Web Cartoonists' Choice Awards. Some well known web cartoonists include Randall Munroe of xkcd, Jeph Jacques of Questionable Content and Jerry Holkins and Mike Krahulik of Penny Arcade.

Creation

Comics artists usually sketch a drawing in pencil before going over the drawing in India ink, using either a dip pen or a brush. Artists may also use a lightbox to create the final image in ink. Some artists, Brian Bolland, for example, use computer graphics, with the published work as the first physical appearance of the artwork. By many definitions (including McCloud's, above), the definition of comics extends to digital media such as webcomics and the mobile comic.

The nature of the comics work being created determines the number of people who work on its creation, with successful comic strips and comic books being produced through a studio system, in which an artist assembles a team of assistants to help create the work. However, works from independent companies, self-publishers, or those of a more personal nature can be produced by a single creator.

Within the comic book industry of North America, the studio system has come to be the main method of creation. Through its use by the industry, the roles have become heavily codified, and the managing of the studio has become the company's responsibility, with an editor discharging the management duties. The editor assembles a number of creators and oversees the work to publication.

Any number of people can assist in the creation of a comic book in this way, from a plotter, a breakdown artist, a penciller, an inker, a scripter, a letterer, and a colorist, with some roles being performed by the same person.

In contrast, a comic strip tends to be the work of a sole creator, usually termed a cartoonist. However, it is not unusual for a cartoonist to employ the studio method, particularly when a strip becomes successful. Mort Walker employed a studio, while Bill Watterson and Charles Schulz did not. Gag, political, and editorial cartoonists tend to work alone as well, though a cartoonist may use assistants.

Tools

Artists use a variety of pencils, brushes, or paper, typically Bristol board, and waterproof ink.[8] When inking, many artists preferred to use a Winsor & Newton Series 7, #3 brush as the main tool, which could be used in conjunction with other brushes, dip pens, a fountain pen, and/or a variety of technical pens or markers. Mechanical tints can be employed to add grey tone to an image. An artist might paint with acrylics, gouache, poster paints, or watercolors. Color can also be achieved through crayons, pastels or colored pencils.

Eraser, rulers, templates, set squares and a T-square assist in creating lines and shapes. A drawing table provides an angled work surface with lamps sometimes attached to the table. A lightbox allows an artist to trace his pencil work when inking, allowing for a looser finish. Knives and scalpels fill a variety of needs, including cutting board or scraping off mistakes. A cutting mat aids paper trimming. Process white is a thick opaque white material for covering mistakes. Adhesives and tapes help composite an image from different sources.

See also

References

- Booker, M. Keith (ed.), Encyclopedia of Comic Books and Graphic Novels, Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2010, p. 573.

- The British Museum. Beer Street, William Hogarth - Fine Art Print Archived 2010-03-03 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 11 April 2010.

- "Satire, sewers and statesmen: why James Gillray was king of the cartoon". The Guardian. 16 June 2015.

- Hess & Northrop 2011, p. 24.

- "The Comics Reporter". Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- MacKenzie, Calum. The Scottish Cartoonists. Glasgow Print Studio Gallery, 1979.

- McLellan, Dennis. "Toon Talk - Two Comic-Strip Artists Discuss the Craft They Love," Los Angeles Times, September 28, 1989.

- "16 essential art tools for artists".

Works cited

- Hess, Stephen; Northrop, Sandy (2011). American Political Cartoons: The Evolution of a National Identity, 1754-2010. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-1119-4.

Further reading

- Steve Edgell, Tim Pilcher, Brad Brooks, The Complete Cartooning Course: Principles, Practices, Techniques (London: Barron's, 2001).

External links

| Look up Cartoonist in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cartoonists. |

Societies and organizations

- Professional Cartoonists' Organisation (UK)

- National Cartoonists Society

- Association of American Editorial Cartoonists

- Society of Illustrators

- Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators

- Society of Illustrators of Los Angeles

- The Association of Illustrators

- The Illustrators Partnership of America

- AIIQ - l’Association des Illustrateurs et Illustratrices du Québec

- Colorado Alliance of Illustrators

- Institute For Archaeologists Graphics Archaeology Group

- Guild of Natural Science Illustrators

- Guild of Natural Science Illustrators-Northwest

- Illustrators Australia

- Newsart

- Australian Cartoonists Association 2Xw7QIe