Charles Dana Gibson

Charles Dana Gibson (September 14, 1867 – December 23, 1944)[1] was an American illustrator. He was best known for his creation of the Gibson Girl, an iconic representation of the beautiful and independent Euro-American woman at the turn of the 20th century.

Charles Dana Gibson | |

|---|---|

Gibson c. 1900 | |

| Born | September 14, 1867 Roxbury, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | December 23, 1944 (aged 77) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Art Students League of New York |

| Known for | Illustration |

Notable work | Gibson Girl series |

| Spouse(s) | Irene Langhorne (m. 1895) |

His wife, Irene Langhorne, and her four sisters inspired his images. He published his illustrations in Life magazine and other major national publications for more than 30 years, becoming editor in 1918 and later owner of the general interest magazine.

Early life

Gibson was born in Roxbury, Massachusetts on September 14, 1867. He was a son of Josephine Elizabeth (née Lovett) and Charles DeWolf Gibson.[2] He had five siblings [3] and was a descendant of U.S. Senators James DeWolf and William Bradford.[4]

A talented youth with an early interest in art, Gibson was enrolled by his parents in New York City's Art Students League, where he studied for two years.[1]

Career

Peddling his pen-and-ink sketches, Gibson sold his first work in 1886 to Life magazine, founded by John Ames Mitchell and Andrew Miller. It featured general interest articles, humor, illustrations, and cartoons. His works appeared weekly in the popular national magazine for more than 30 years. He quickly built a wider reputation, with his drawings being featured in all the major New York publications, including Harper's Weekly, Scribners and Collier's. His illustrated books include the 1898 editions of Anthony Hope's The Prisoner of Zenda and its sequel Rupert of Hentzau as well as Richard Harding Davis' Gallegher and Other Stories[5]

His wife and her elegant Langhorne sisters also inspired his famous Gibson Girls, who became iconic images in early 20th-century society. Their dynamic and resourceful father Chiswell Langhorne had his wealth severely reduced by the Civil War, but by the late 19th century, he had rebuilt his fortune on tobacco auctioneering and the railroad industry.[6][7]

After the death of John Ames Mitchell in 1918, Gibson became editor of Life and later took over as owner of the magazine. As the popularity of the Gibson Girl faded after World War I, Gibson took to working in oils for his own pleasure. In 1918, he was elected into the National Academy of Design as an Associate member,[8] and became a full Academician in 1932.[9]

He retired in 1936, the same year Scribner's published his biography, Portrait of an Era as Drawn by C. D. Gibson: A Biography by Fairfax Downey. At the time of his death in 1944, he was considered "the most celebrated pen-and-ink artist of his time as well as a painter applauded by the critics of his later work."[10]

Personal life

On November 7, 1895, Gibson was married to Irene Langhorne (1873–1956), a daughter of railroad industrialist Chiswell Langhorne.[11] Irene was born in Danville, Virginia, and was one of five sisters, all noted for their beauty, including Nancy Astor, Viscountess Astor,[12] the first woman to serve as a Member of Parliament in the British House of Commons.[13] Together, Irene and Charles were the parents of two children:[3]

- Irene Langhorne Gibson (1897–1973),[14] who married George Browne Post III (1890–1952), a grandson of architect George B. Post, in 1916.[15] They divorced and she married real estate developer John Josiah Emery (1898–1976) in 1926.

- Langhorne Gibson (1899–1982),[16] who married Marion Taylor (1902–1960) in 1922.[17] He later married Parthenia Burke Ross (1911–1998) in 1936.[18]

For part of his career, Gibson lived in New Rochelle, New York, a popular art colony among actors, writers and artists of the period. The community was most well known for its unprecedented number of prominent American illustrators.[19] Gibson also owned an island off Islesboro, Maine which came to be known as 700 Acre Island; he and his wife spent an increasing amount of time here through the years.[20]

Gibson died of a heart ailment in 1944, aged 77, at 127 East 73rd Street, his home in New York City.[1] After a private funeral service at the Gibson home in New York, he was interred at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[21] His widow died at her home in Greenwood, Virginia in April 1956 at the age of 83.[11]

Legacy

Almost unrestricted merchandising saw his distinctive sketches appear in many forms. The Gibson cocktail has been claimed to be named after him, as it is said he favored ordering gin martinis with a pickled onion garnish in place of the traditional olive or lemon zest.

Work

Frontispiece to The Prisoner of Zenda, 1898

Frontispiece to The Prisoner of Zenda, 1898 Illustration from Rupert of Hentzau, 1898

Illustration from Rupert of Hentzau, 1898 At the Beach, 1901

At the Beach, 1901 Fancy Dress, 1901

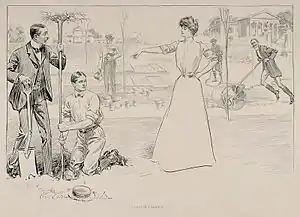

Fancy Dress, 1901 Love in a Garden, 1901

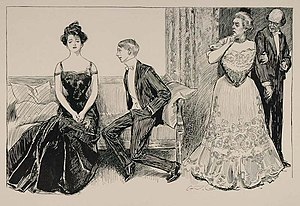

Love in a Garden, 1901 The Crush, 1901

The Crush, 1901 Art Lesson, 1901

Art Lesson, 1901 Everything in the World That Money Can Buy, 1901

Everything in the World That Money Can Buy, 1901 Stepped On, 1901

Stepped On, 1901 Fanned Out, 1914

Fanned Out, 1914_Studies_in_expression._When_women_are_jurors_(compressed).jpg.webp) Studies in Expression: When Women Are Jurors, 1902

Studies in Expression: When Women Are Jurors, 1902 March 26, 1925 Life cover by Gibson

March 26, 1925 Life cover by Gibson

References

- "CHARLES D. GIBSON DEAD AT AGE OF 77; Famed Illustrator, Creator of 'Gibson Girl,' Succumbs to Heart Ailment in Home LAUNCHED VOGUE OF '90'S Noted for His Lighter Works, He Also Gained Recognition for His Paintings in Oils" (PDF). The New York Times. 24 December 1944. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- Rossiter Johnson, John Howard Brown (1904). The twentieth century biographical dictionary of notable Americans. The Biographical Society.

- Stockwell, Mary Le Baron Esty, 1850– (1904). Descendants of Francis Le Baron of Plymouth, Mass. T.R. Marvin & Son, printers. OCLC 359772.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Laura Barbeau (December 1979). "LONGFIELD (Gibson House) HABS No.RI-129" (PDF). Historic American Buildings Survey. National Park Service. Retrieved 2010-06-29.

- Davis, Richard Harding (1905) [1891]. "Frontispiece". Gallegher and Other Stories. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. OCLC 168633.

- "Charles Dana Gibson and his wife at their Islesboro, Maine, home", mainememory.net; accessed September 2, 2017.

- "Mrs. Gibson, the original Gibson girl", Maine Memory Network; accessed September 2, 2017.

- "All National Academicians (1825 - Present)". National Academy of Design. Retrieved 2020-02-26.

- "National Academicians – Past Academicians Archived 2014-01-16 at the Wayback Machine". National Academy. nationalacademy.org; retrieved March 19, 2017.

- "Charles Dana Gibson" (PDF). The New York Times. 25 December 1944. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- Times, Special to The New York (21 April 1956). "Mrs. Charles Dana Gibson Dies; Original Model for Gibson Girl; Widow of Artist Was One of Five Langhorne Sisters --Symbol of Nineties American Ideal of Beauty Founded Alliance Branch" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- "ASTORS TO VISIT MAINE.; Will Spend August With the Charles Dana Gibson Family" (PDF). The New York Times. 11 June 1926. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- Langhorne House, 117 Broad Street, Danville, Va., virginia.org Archived 2008-06-02 at the Wayback Machine

- "Mrs. John J. Emery" (PDF). The New York Times. 2 August 1973. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- "MRS. G.B. POST JR. ASKS PARIS DIVORCE; Former Irene Langhorne Gibson Accuses Her Husband of Desertion" (PDF). The New York Times. 16 February 1926. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- "Langhorne Gibson, 82 Writer and Artist's Son". The New York Times. 12 July 1982. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- "MISS TAYLOR TO WED LANGHORNE GIBSON; Daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Moses Taylor Engaged to Son of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Dana Gibson" (PDF). The New York Times. 1 July 1922. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- "PARTHENIA B. ROSS HAS HOME BRIDAL Mrs. PauI.Downing's Daughter Wed to Langhorne Gibson, Nephew of Lady Astor. WILL VISIT WEST INDIES Bridegroom, Author of Books on Naval History, Is Executive of Life and Son of Noted Artist" (PDF). The New York Times. January 10, 1936. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- Progressive Architecture – Volume 3, 1922, google.com; accessed September 2, 2017.

- Charles Dana Gibson at his Islesboro home, vintagemaineimages.com Archived March 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "RITES FOR C. D. GIBSON; Relatives and Friends Attend Service at Artist's Home" (PDF). The New York Times. 27 December 1944. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

Sources

- Bulloch, J. M. (1896). "Charles Dana Gibson". The Studio. Vol. VIII. pp. 75–81. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- Davis, Charles Belmont (January 1899). "Mr. Charles Dana Gibson and His Art". The Critic. Vol. XXXIV no. 859. pp. 48–55. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- Gelman, Woody, ed. (1969). The Best of Charles Dana Gibson. New York: Bounty Books. OCLC 71597.

- Gibson, Charles Dana (1969). Edmund Vincent Gillon, Jr. (ed.). The Gibson Girl and Her America: The Best Drawings of Charles Dana Gibson. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 9780486219868. OCLC 1112853195.

- —— (1905). Sketches in Egypt. New York: Doubleday & McClure Co. OCLC 3537342. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- Marden, Orison Swett (1905). "Chapter XXXIII: Being Himself in Style and Subjects, the Secret of an Artist's Wonderful Popularity: Charles Dana Gibson, Originator of the 'Gibson Girl'". Little Visits with Great Americans. New York: The Success Company. pp. 342–352. OCLC 5292021. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Dana Gibson. |

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Works by Charles Dana Gibson at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Charles Dana Gibson at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Charles Dana Gibson at Internet Archive

- Charles Dana Gibson at Find a Grave