Caspian Sea Monster

The KM (Korabl Maket) (Russian: Корабль-макет, literally "Ship-prototype"), known colloquially as the Caspian Sea Monster, was an experimental ground effect vehicle developed in the Soviet Union in the 1960s by the Central Hydrofoil Design Bureau. The KM began operation in 1966, and was continuously tested by the Soviet Navy until 1980 when it crashed into the Caspian Sea.

| KM | |

|---|---|

| |

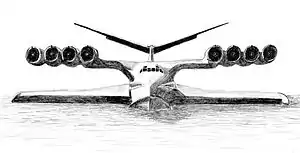

| Artist's illustration of the KM | |

| Role | Ekranoplan |

| National origin | Soviet Union |

| Manufacturer | Central Hydrofoil Design Bureau |

| Designer | Rostislav Alexeyev |

| First flight | October 16, 1966 |

| Introduction | 1964 |

| Retired | 1980 |

| Status | Destroyed in 1980 |

| Primary user | Soviet Navy |

| Produced | 1964–1966 |

| Number built | 1 |

The KM was the largest and heaviest aircraft in the world from 1966 to 1988, and its surprise discovery by the United States and the subsequent attempts to determine its purpose became a distinctive event of espionage during the Cold War.

Design and development

The KM was an experimental aircraft developed from 1964 to 1966, during a time when the Soviet Union saw interest in ground effect vehicles—airplane-like vehicles that use ground effect to fly several meters above surfaces, primarily bodies of water (such as the Caspian Sea). It was designed at the Central Hydrofoil Design Bureau, by the chief designer Rostislav Alexeyev and the lead engineer V. Efimov, and manufactured at the Red Sormovo plant in Gorky (now Nizhny Novgorod).[1][2][3][4] The KM was among the earliest major ekranoplan (English: "screen effect") projects and was notable for its massive size and payload, becoming the largest aircraft in the world when it was completed in 1966. The KM had a wingspan of 37.6 metres (123 ft); a length of 92 m (302 ft); a maximum take-off weight of 544 short tons (494 t); and was designed to fly at an altitude of 5–10 metres (16–33 ft) to use the ground effect. The KM was also undetectable to many radar systems, as it flew below the minimum altitude of detection. Despite technically being an aircraft, it was considered by the authorities to be closer to a boat and was assigned to the Soviet Navy, but operated by test pilots of the Soviet Air Forces. The KM was documented as a marine vessel and prior to the first flight a bottle of champagne was broken against its nose, a tradition for the first voyage of a watercraft.

Operational history

On June 22, 1966, the completed KM began transportation along the Volga River to the testing grounds on the Caspian Sea near the town of Kaspiysk. It was transported from Gorky along the river in secret, covered in camouflage and moving only at night. The aircraft's first flight was on October 16, 1966, performed by V. Loginov and Rostislav Alexeyev himself, which was very unusual as most Soviet aircraft designers never piloted their own creations. All the work was conducted under patronage of the Ministry of Shipbuilding Industry. Testing showed the KM to have an optimum (fuel efficient) cruising speed of 430 km/h (267 mph, 232 knots), and a maximum operational speed of 500 km/h (311 mph, 270 knots). The maximum speed achieved was 650 km/h (404 mph, 350 knots), although some sources claim up to 740 km/h (460 mph, 400 knots).[2][5]

The KM was at first seen as a promising vehicle specialized for use by military and rescue workers but its design caused many difficulties; progress slowed and Alexeyev moved on to other ekranoplan projects. It was tested on the Caspian Sea for an extensive 15 years until 1980, when it was destroyed following a crash caused by pilot error. There were no human casualties, but the KM was damaged and no attempts were made to save it, it being left to float before eventually sinking a week later. The KM was deemed too heavy to recover and has remained underwater at the crash site ever since, with no plans to build a second ever made.[6] However, the KM later became the basis for the Lun-class ekranoplan developed by the Central Hydrofoil Design Bureau in the 1980s, which saw one example, the MD-160, enter service with the Soviet Navy and later the Russian Navy before being decommissioned in the late 1990s. The aircraft was not destroyed, but abandoned in the Caspian Sea, being visible in 2020.[7] After more than three decades, the aircraft was moved in 2020 to Derbent, with plans to make it the star of Derbent's planned Patriot Park, a military museum and theme park that will display a variety of Soviet and Russian military equipment.[8]

The KM remained the largest aircraft in the world during the entirety of its existence and is the second-largest aircraft ever built, behind the Antonov An-225 Mriya that flew for the first time in 1988, eight years after the KM's destruction.

Western discovery

The secret Soviet KM project was discovered by the United States in 1967, when photographs taken from spy satellites showed the KM taxiing during testing near Kaspiysk. The strange aircraft puzzled intelligence agencies in the Western world, noting the small stubby wings despite its large size, as well as the "KM" markings and flag of the Soviet Navy on its fuselage. The United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) branded the aircraft the "Kaspian Monster" after the KM markings, it later became known as the "Caspian Sea Monster", while "KM" actually stood for Korabl-maket meaning "Prototype ship" in Russian. The discovery, at the height of the Cold War, greatly concerned the CIA, which set up a dedicated task force and developed a purpose-built unmanned drone under Project AQUILINE, just to determine what the secret behind the vehicle was. The KM was initially assumed to be an unfinished conventional aircraft, but it was quickly determined that the vehicle could not fly high. In the 1980s, after the KM was already destroyed, the United States discovered it was a large ekranoplan. The development of ground effect vehicles was not as widespread in the West as in the Soviet Union.

In media

- The 2006 video game Microsoft Flight Simulator X features the KM in a mission. The Deluxe Edition contains additional missions, one of which also depicts the KM.

- Episode 1 of the 2008 series James May's Big Ideas, entitled "Come Fly With Me", features the story of the KM.

- The 2007 Japanese animated film Evangelion: 1.0 You Are (Not) Alone features a version of the KM.

- The 2016 PC game Soviet Monsters: Ekranoplans features several ekranoplans, including the KM.[9]

- In the James Bond continuation novel Devil May Care published in 2008, the KM is used by the villain for smuggling.

- In the 007: Blood Stone video game the villain also uses an ekranoplan in an effort to escape from James Bond, but the latter gets onboard and throws the villain off the vehicle, killing him. Later the ekranoplan can be seen docked and cleaned.

Specifications (KM)

Data from The Osprey Encyclopedia of Russian Aircraft 1875–1995,[10] Russia's Ekranoplans:The Caspian Sea Monster and other WiG Craft[1]

General characteristics

- Crew: 5

- Capacity: 50 people

- Length: 92.00 m (301 ft 10 in)

- Wingspan: 37.60 m (123 ft 4 in) * Tail stabilizer span: 37 m (121 ft 5 in)

- Height: 21.80 m (71 ft 6 in)

- Wing area: 662.50 m2 (7,131.1 sq ft)

- Empty weight: 240,000 kg (529,109 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 544,000 kg (1,199,315 lb)

- Powerplant: 10 × Dobrynin VD-7 turbojet, 127.53 kN (28,670 lbf) thrust each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 500 km/h (310 mph, 270 kn)

- Cruise speed: 430 km/h (270 mph, 230 kn)

- Range: 1,500 km (930 mi, 810 nmi)

- Ground effect altitude: 4–14 m (13 ft 1 in–45 ft 11 in)

- Maximum sea state: 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in)

See also

References

- Komissarov, Sergey (2002). Russia's Ekranoplans:The Caspian Sea Monster and other WiG Craft. Hinkley: Midland Publishing. ISBN 978-1857801460.

- National Research Council Committee to Perform a Technology Assessment Focused on Logistics Support Requirements for Future Army Combat Systems; Reducing the Logistics Burden for the Army After Next, 1999, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, p. 68

- Liang Yun, Alan Bliault; High Performance Marine Vessels; p. 89 (2012)

- Anne H. Cahn; Killing Détente: The Right Attacks the CIA; p. 65 (1998)

- "Caspian Sea Monster". Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- The Register; In search of the Caspian Sea Monster; Lester Haines; 22 September 2006

- Mizokami, Kyle (2020-08-27). "A Towing Gone Wrong Has Left Russia's Flying Sea Monster Stranded Off the Beach". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- Miquel Ros. "The 'Caspian Sea Monster' rises from the grave". CNN. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- Soviet Monsters: Ekranoplans

- Gunston, Bill (1995). The Osprey Encyclopedia of Russian Aircraft 1875–1995. London: Osprey Aerospace. pp. 512–513. ISBN 978-1855324053.