Cass Gilbert

Cass Gilbert (November 24, 1859 – May 17, 1934) was a prominent American architect.[1][2][3] An early proponent of skyscrapers, his works include the Woolworth Building, the United States Supreme Court building, the state capitols of Minnesota, Arkansas and West Virginia; and the Saint Louis Art Museum and Public Library. His public buildings in the Beaux Arts style reflect the optimistic American sense that the nation was heir to Greek democracy, Roman law and Renaissance humanism.[4] Gilbert's achievements were recognized in his lifetime; he served as president of the American Institute of Architects in 1908–09.

Cass Gilbert | |

|---|---|

Gilbert in 1907 | |

| Born | November 24, 1859 Zanesville, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | May 17, 1934 (aged 74) New York City, New York |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Awards | President, American Institute of Architects, 1908–09 |

| Buildings | Woolworth Building, United States Supreme Court building |

Gilbert was a conservative who believed architecture should reflect historic traditions and the established social order. His design of the new Supreme Court building (1935), with its classical lines and small size, contrasted sharply with the large federal buildings going up along the National Mall in Washington, D.C., which he disliked.[5]

Heilbrun says "Gilbert's pioneering buildings injected vitality into skyscraper design, and his 'Gothic skyscraper,' epitomized by the Woolworth Building, profoundly influenced architects during the first decades of the twentieth century."[6] Christen and Flanders note that his reputation among architectural critics went into eclipse during the age of modernism, but has since rebounded because of "respect for the integrity and classic beauty of his masterworks".[7]

Early life

Gilbert was born in Zanesville, Ohio, the middle of three sons, and was named after the statesman Lewis Cass, to whom he was distantly related.[3] Gilbert's father General Samuel A. Gilbert was a Union veteran of the American Civil War and a surveyor for the United States Coast Survey. His uncle was Union Gen. Charles Champion Gilbert.[8][9][10] When he was nine, Gilbert's family moved to St. Paul, Minnesota, where he was raised by his mother after his father died. He attended preparatory school but dropped out of Macalester College. He began his architectural career at age 17 by joining the Abraham M. Radcliffe office in St. Paul. In 1878, Gilbert enrolled in the architecture program at MIT.[11]

Minnesota career

Gilbert later worked for a time with the firm of McKim, Mead & White before starting a practice in St. Paul with James Knox Taylor. He was commissioned to design a number of railroad stations, including those in Anoka, Willmar and the still-extant Little Falls depot, all in Minnesota.[3] As a Minnesota architect he was best known for his design of the Minnesota State Capitol and the downtown St. Paul Endicott Building.[12] His goal was to move to New York City and gain a national reputation, but he remained in Minnesota from 1882 until 1898. Many of his Minnesota buildings are still standing, including more than a dozen private residences (especially those on St. Paul's Summit Avenue), several churches featuring rich textures and colors, resort summer homes, and warehouses.[12]

National reputation

The completion of the Minnesota capitol gave Gilbert his national reputation and in 1898 he permanently moved his base to New York. His breakthrough commission was the design of the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House in New York City, which now houses the George Gustav Heye Center.[3] Gilbert served on the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts from 1910 to 1916.[13] In 1906 he was elected into the National Academy of Design as an Associate member, and became a full Academician in 1908. Gilbert served as President of the Academy from 1926 to 1933.

Historical impact

Gilbert was a skyscraper pioneer; when designing the Woolworth Building he moved into unproven ground — though he certainly was aware of the ground-breaking work done by Chicago architects on skyscrapers and once discussed merging firms with the legendary Daniel Burnham — and his technique of cladding a steel frame became the model for decades.[3] Modernists embraced his work: John Marin painted it several times; even Frank Lloyd Wright praised the lines of the building, though he decried the ornamentation.

Gilbert was one of the first celebrity architects in America, designing skyscrapers in New York City and Cincinnati, campus buildings at Oberlin College and the University of Texas at Austin, state capitols in Minnesota and West Virginia, the support towers of the George Washington Bridge, railroad stations (including the New Haven Union Station, 1920),[14] and the United States Supreme Court building in Washington, D.C.. His reputation declined among some professionals during the age of Modernism, but he was on the design committee that guided and eventually approved the modernist design of Manhattan's groundbreaking Rockefeller Center. Gilbert's body of work as a whole is more eclectic than many critics admit. In particular, his Union Station in New Haven lacks the embellishments common of the Beaux-Arts period and contains the simple lines common in Modernism.

Gilbert wrote to a colleague, "I sometimes wish I had never built the Woolworth Building because I fear it may be regarded as my only work and you and I both know that whatever it may be in dimension and in certain lines it is after all only a skyscraper."[15]

Gilbert's two buildings on the University of Texas at Austin campus, Sutton Hall (1918) and Battle Hall (1911), are recognized by architectural historians as among the finest works of architecture in the state. Designed in a Spanish-Mediterranean revival style, the two buildings became the stylistic basis for the later expansion of the university in the 1920s and 1930s and helped popularize the style throughout Texas.

Archives

Gilbert's drawings and correspondence are preserved at the New-York Historical Society, the Minnesota Historical Society, the University of Minnesota, and the Library of Congress.

Notable works

- Saint Paul Seminary, Saint Paul, Minnesota.

- Cretin Hall, Loras Hall, a gymnasium (now the Service Center), a classroom building, the refectory building, and the administration building in 1894 were commissioned by James J. Hill. Only Cretin, Loras, and the Service Center still stand.

- Minnesota State Capitol, Saint Paul, Minnesota, 1895–1905.

- Designed in High Renaissance style, the building is not a replica of the United States Capitol. Local newspapers made a fuss when Gilbert sent to Georgia for marble, but the result, in which a hemispherical dome caps a high drum not unlike that of St. Peter's Basilica, crowning a building housing the bicameral legislature and the state supreme court, was so nobly handsome that West Virginia and Arkansas contracted for Gilbert capitols as well. Its brick dome is held in hoops of steel.

- St. Clement's Episcopal Church, St. Paul, Minnesota, 1895.

- Designed in the traditional English country church style, with a lychgate and close, bell tower, and parish hall (renovated in 2006). Funded by a generous donation from Mrs. Theodore Eaton, widow of the rector of St. Clement's Episcopal Church in New York City. Includes original furniture, baptismal font, encaustic tile floor in choir, elaborate rood screen, linen-fold paneling, and parquet oak floor in sanctuary. The altar features Tiffany Studios stained glass window depicting the empty cross.

- Northern Pacific Railway Depot, 701 Main Street, Fargo, North Dakota, 1898.[14]

- The Broadway-Chambers Building (277 Broadway), Manhattan, 1899–1900.

- Gilbert's first building in New York City.[16]

- Essex County Courthouse, Newark, 1904

- Saint Louis Art Museum (Palace of the Fine Arts), St. Louis, Missouri, 1904.

- Built for the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis and the only major building of the fair built as a permanent structure.

- Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House, Manhattan, 1902–1907.

- Facing Bowling Green park in Lower Manhattan

- 90 West Street, Manhattan, 1905–1907.

- Severely damaged during the September 11, 2001 attacks, this building in lower Manhattan has since been completely restored.[17]

- Designs for 12 local stations on the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad in the Bronx and Westchester County, New York, 1908. Not all were built, and only four were extant in 2014, all in the Bronx: the Westchester Avenue station and Bartow station are in ruins, and the Morris Park and Hunts Point stations have been converted to other uses. All ceased to be used as railroad stations by the late 1930s.[18]

- Metals Bank Building, Butte, Montana, 1906.

- Commissioned by F. Augustus Heinze, this eight-story low-rise building has an internal steel frame. It was the second to be built in Butte after the 1901 Hirbour Building, which also has eight stories.

- A series of master plans for the Minneapolis campus of the University of Minnesota, 1907.[19][20]

- Spalding Building, Portland, Oregon, 1911.

- A 12-story early skyscraper based on the construction principles of a classical column.

- Battle Hall, Austin, Texas, 1911.

- For the University of Texas at Austin.[21]

- New Haven Free Public Library, Mary E. Ives Memorial Library

- At the corner of Elm and Temple Streets in downtown New Haven, architect Gilbert designed the brick and marble building to harmonize with the traditional architecture of New Haven, and especially with the United Church nearby. The building was formally dedicated to the City of New Haven on May 27, 1911.

- Kelsey Building, Trenton, New Jersey, 1911.

- Built by Henry Cooper Kelsey as a memorial to his wife. Now used by Thomas Edison State University.[22]

- St. Louis Public Library, St. Louis, Missouri, 1912

- The main library for the city's public library system, in a severe classicizing style, has an oval central pavilion surrounded by four light courts. The outer facades of the free-standing building are of lightly rusticated Maine granite. The Olive Street front is disposed like a colossal arcade, with contrasting marble bas-relief panels. A projecting three-bay central block, like a pared-down triumphal arch, provides a monumental entrance. At the rear the Central Library faced a sunken garden. The interiors feature some light-transmitting glass floors. The ceiling of the Periodicals Room is modified from Michelangelo's ceiling in the Laurentian Library.[23][24]

- Woolworth Building, Manhattan, New York, 1913.

- A Gothic Revival skyscraper clad in glazed terracotta panels, it was the tallest building in the world when built. Bas-reliefs in the lobby depict Woolworth and Gilbert with Woolworth holding nickels and dimes.

- Fourth and Vine Tower, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1913.

- Originally built as the headquarters for the Union Central Life Insurance Company.

- Austin, Nichols and Company Warehouse, Williamsburg, Brooklyn, New York, 1915.

- Fountain, Ridgefield, Connecticut, 1914–16.

- This fountain, at the intersection of Routes 35 and 33, was designed and donated to the town by Cass Gilbert, who had a home within sight of the intersection. In 2004, a drunk driver crashed into the fountain, heavily damaging it; the fountain was rebuilt, raised higher, and surrounded by protective plantings, and it is still functioning today.[25]

- Four buildings at Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio

- Gilbert designed four buildings at Oberlin: Finney Chapel (1909), the Cox Administration Building (1915), the Allen Memorial Art Museum, and Bosworth Hall (1931). He enjoyed a close working relationship with Oberlin's president Henry Churchill King, but his relationship with Oberlin deteriorated after King retired in 1927 and most of the design work and construction supervision of Bosworth Hall and its residential quadrangle was done by Gilbert's son Cass Jr., who had earlier supervised the construction of the Allen Memorial Hospital (1924) in Oberlin (now Mercy Allen Medical Center).

- Rodin Studios, Midtown Manhattan, New York, 1916–1917.

- Chase Headquarters Building, Waterbury, Connecticut, 1917-1919.

- This building was designed as the headquarters of the Chase Company and forms part of the Waterbury Municipal Center Complex, a unique concentration of Gilbert's architecture comprising the Waterbury City Hall, the Chase Bank Building and the Chase company headquarters, Chase's house, a dispensary and Lincoln House, a headquarters building for the city's charities.

- G. Fox & Co. department store, Hartford, Connecticut, 1918.

- Brooklyn Army Terminal, Sunset Park, Brooklyn, New York, 1919.

- Treasury Annex, Lafayette Park, Washington, D.C., 1919.

- The Detroit Public Library, main branch, 1921.

- The First Division Monument, President's Park, Washington D.C., 1924.[26]

- West Virginia State Capitol, Charleston, West Virginia, 1924–1932.

- The James Scott Memorial Fountain, Belle Isle, Detroit, MI, 1925.

- United States Chamber of Commerce headquarters, Washington, D.C., 1925.

- Plans for cladding the George Washington Bridge support towers, New York–New Jersey, in masonry, 1926. Not carried out.

- New York Life Building, 1926.

- Gibraltar Building, 1927.

- R. C. Williams Warehouse, Chelsea, Manhattan, New York, 1919.

- headquarters for Prudential Insurance in Newark

- Embassy of the United States in Canada (100 Wellington Street), Ottawa, 1932.

- United States Supreme Court Building, Washington, D.C., 1935.[21]

- Gilbert's last major project, guided to completion by his son, Cass Gilbert Jr. He died a year before it was completed. A vast Roman temple in the Corinthian order is penetrated by a cross range articulated with pilasters in very low relief. The central tablet in the richly sculpted frieze reads EQUAL JUSTICE UNDER LAW. His design for the U.S. Supreme Court chambers was based upon his design for the West Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals at the state capitol in Charleston. The pediment sculptures Liberty attended by order and Authority (great lawgivers Moses, Confucius, and Solon are on the West Portico) were executed by Hermon Atkins MacNeil.

- Thurgood Marshall United States Courthouse, Manhattan, 1933.

Gallery

Minnesota State Capitol, St. Paul, Minnesota (1895–1905)

Minnesota State Capitol, St. Paul, Minnesota (1895–1905) St. Louis Art Museum, St. Louis, Missouri (built for the 1904 World's Fair)

St. Louis Art Museum, St. Louis, Missouri (built for the 1904 World's Fair) The Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House, New York, New York (1907)

The Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House, New York, New York (1907) Finney Chapel, Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio (1909)

Finney Chapel, Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio (1909) Spalding Building, Portland, Oregon (1911)

Spalding Building, Portland, Oregon (1911) Woolworth Building, New York, New York (1913)

Woolworth Building, New York, New York (1913)

Cox Administration Building, Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio (1915)

Cox Administration Building, Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio (1915).jpg.webp) Brooklyn Army Terminal, Brooklyn, New York (1919)

Brooklyn Army Terminal, Brooklyn, New York (1919) Treasury Annex, Washington. D.C. (1919)

Treasury Annex, Washington. D.C. (1919) Detroit Public Library, Detroit, Michigan (1921)

Detroit Public Library, Detroit, Michigan (1921) United States Chamber of Commerce headquarters, Washington, D.C. (1925)

United States Chamber of Commerce headquarters, Washington, D.C. (1925) New York Life Insurance Building, New York, New York (1926)

New York Life Insurance Building, New York, New York (1926) Northern Pacific Railway Depot, Little Falls, Minnesota

Northern Pacific Railway Depot, Little Falls, Minnesota Northern Pacific Railway Depot, Helena, Montana

Northern Pacific Railway Depot, Helena, Montana Northern Pacific Railway Depot, Bismarck, North Dakota

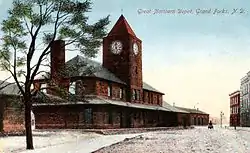

Northern Pacific Railway Depot, Bismarck, North Dakota Great Northern Railway Depot, Grand Forks, North Dakota

Great Northern Railway Depot, Grand Forks, North Dakota Bosworth Hall, Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio (1931)

Bosworth Hall, Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio (1931)

United States Supreme Court Building, Washington, D.C. (1935)

United States Supreme Court Building, Washington, D.C. (1935)

Name confusion with C. P. H. Gilbert

Cass Gilbert is often confused with Charles Pierrepont Henry Gilbert, another prominent architect of the time. Cass Gilbert designed the famous Woolworth Building skyscraper on Broadway for Frank W. Woolworth, while Woolworth's personal mansion was designed by C. P. H. Gilbert. The Ukrainian Institute building on Manhattan's 5th Avenue is the work of C. P. H. Gilbert, and often incorrectly attributed to Cass Gilbert.[27][28]

Cass Gilbert is sometimes also confused with his son, architect Cass Gilbert, Jr.

References

Notes

- Urbanielli, Elissa (ed.) "Broadway–Chambers Building Designation Report" Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (January 14, 1992), pp. 1 & 4. "...designed by the prominent architect, Cass Gilbert ... he went on to enjoy an illustrious career of national extent..."

- Robins, Anthony W. "Woolworth Building Designation Report" Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (April 12, 1983) p. 6. "Cass Gilbert ... was one of the most important architects to work in New York."

- Christen, Barbara S.; Flanders, Steven (2001). Cass Gilbert, Life and Work: Architect of the Public Domain. W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-73065-4.

- Blodgett, Geoffrey (1999). Cass Gilbert: The Early Years. Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-87351-410-6.

- Geoffrey Blodgett, "Cass Gilbert, Architect: Conservative at Bay," Journal of American History, December 1985, Vol. 72 Issue 3, pp. 615–636 in JSTOR

- Margaret Heilbrun, Inventing the skyline: the architecture of Cass Gilbert (Columbia U.P. 2000) p xxxv

- Barbara S. Christen and Steven Flanders, eds. Cass Gilbert, Life and Work: Architect of the Public Domain (2001) p 72

- Christen, Barbara S; Flanders, Steven, eds. (17 November 2001). Cass Gilbert, Life and Work: Architect of the Public Domain. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 293. ISBN 978-0393730654. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

Chapter 1, footnote 4

- Blodgett, Geoffrey (15 November 2001). Cass Gilbert: The Early Years (First ed.). Minnesota Historical Society Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0873514101. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- "Brevet Brig. General Samuel A. Gilbert (USA)". Geni.com. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- Irish, Sharon (1999). Cass Gilbert, Architect. Monacelli. ISBN 1-885254-90-3.

- Irish, Sharon. "West Hails East: Cass Gilbert in Minnesota" Minnesota History, April 1993, Vol. 53 Issue 5, pp 196–207

- Thomas E. Luebke, ed., Civic Art: A Centennial History of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, 2013): Appendix B, p. 545.

- Potter, Janet Greenstein (1996). Great American Railroad Stations. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 70, 380. ISBN 978-0471143895.

- Letter to Ralph Adams Cram, 1920 quoted in Goldberger, Paul (2001) Cass Gilbert, "Remembering the turn-of-the-century urban visionary", Architectural Digest, February issue, pp. 106–102

- "Broadway-Chambers Building". New York Architecture Images. Retrieved 2007-01-26.

- "National Trust Presents National Preservation Honor Award to 90 West Street in Lower Manhattan". 2006-11-02. Retrieved 2007-08-22.

- Gray, Christopher (25 November 2009). "Where Ghost Passengers Await Very Late Trains". New York Times. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- "University of Minnesota Campus Plan (1907-10)". Cass Gilbert Society. Retrieved 2009-01-28.

- "Cass Gilbert Plan". University of Minnesota Sesquicentennial History. 2000-06-01. Archived from the original on 2007-01-08. Retrieved 2007-01-26.

- "Study for Woolworth Building, New York". World Digital Library. 1910-12-10. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- "Kelsey Building". Thomas Edison State University. Archived from the original on 2019-09-03. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- "St. Louis Public Library". St. Louis Public Library Fact Sheer. Archived from the original on 2006-12-17. Retrieved 2007-01-26.

- Stocker EB (1985). "St. Louis Public Library". Journal of Library History. 20 (3): 310–12. Archived from the original on 2007-01-12.

- The Ridgefield Press, various issues.

- "First Division Monument". National Park Service. 2006-09-08. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- Gray, Christopher (2003-02-09). "Streetscapes/Charles Pierrepont Henry Gilbert; A Designer of Lacy Mansions for the City's Eminent". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- "About the Ukrainian Institute of America". Ukrainian Institute of America. Archived from the original on 2011-05-22. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

Further reading

- Christen, Barbara S. and Flanders, Steven (editors). Cass Gilbert, Life and Work: Architect of the Public Domain New York: W.W. Norton, 2001.

- Moutschen, Joseph. Architecture américaine – Une interview de l'architecte qui a construit la plus haute maison du monde (Cass Gilbert); in L'Equerre: Janvier 1930 p. 177; Février 1930 p. 187; Mars 1930, p. 196; L'Equerre, 1928–1939; Edition Foure-Tout, 2010, pp. 1350; ISBN 978-2-930525-12-9

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cass Gilbert. |

- Cass Gilbert in MNopedia, the Minnesota Encyclopedia

- Cass Gilbert at archINFORM

- Cass Gilbert Society

- Architecture

- Archival collections

- Cass Gilbert Collection, 1897–1936 Archives Center, National Museum of American History

- Cass Gilbert Papers, Minnesota Historical Society.

- Guide to the Cass Gilbert collection, 2005 Abstract of the Gilbert papers from the New-York Historical Society

- Cass Gilbert collection, University Archives, University of Minnesota – Twin Cities

- Selected Cass Gilbert Architectural Drawings of the Detroit Public Library at Wayne State University Library contains 19 presentation drawings by Cass Gilbert of the Detroit Public Library, which he designed in 1921.

- Cass Gilbert Archival card catalog. Held by the Department of Drawings & Archives, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

- Selected Cass Gilbert Architectural Drawings and Plans for the Woolworth Building at Vanderbilt University Fine Arts Gallery contains around 200 works