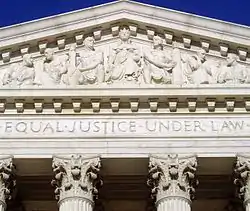

Equal justice under law

Equal justice under law is a phrase engraved on the West Pediment, above the front entrance of the United States Supreme Court building in Washington D.C. It is also a societal ideal that has influenced the American legal system.

The phrase was proposed by the building's architects, and then approved by judges of the Court in 1932. It is based upon Fourteenth Amendment jurisprudence, and has historical antecedents dating back to ancient Greece.

Proposed by architects and approved by justices

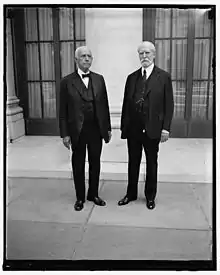

This phrase was suggested in 1932 by the architectural firm that designed the building.[1] Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes and Justice Willis Van Devanter subsequently approved this inscription, as did the United States Supreme Court Building Commission which Hughes chaired (and on which Van Devanter served).[2][3]

The architectural firm that proposed the phrase was headed by Cass Gilbert, though Gilbert himself was much more interested in design and arrangement, than in meaning.[4] Thus, according to David Lynn who at that time held the position of Architect of the Capitol, the two people at Gilbert's firm who were responsible for the slogan "equal justice under law" were Gilbert's son (Cass Gilbert, Jr.) and Gilbert's partner, John R. Rockart.[3]

In 1935, the journalist Herbert Bayard Swope objected to Chief Justice Hughes about this inscription, urging that the word "equal" be removed because such a "qualification" renders the phrase too narrow; the equality principle would still be implied without that word, Swope said. Hughes refused, writing that it was appropriate to "place a strong emphasis upon impartiality".[3]

This legal soundbite atop the Court is perceived differently by different people, sometimes as ostentatious, often as profound, and occasionally as vacuous.[5] According to law professor Jim Chen, it is common for people to "suggest that disagreement with some contestable legal proposition or another would be tantamount to chiseling or sandblasting 'Equal Justice Under Law' from the Supreme Court's portico."[5] The phrase may be perceived in a variety of ways, but it very distinctly does not say "equal law under justice", which would have meant that the judiciary can prioritize justice over law.[6]

Based upon Fourteenth Amendment jurisprudence

The words "equal justice under law" paraphrase an earlier expression coined in 1891 by the Supreme Court.[7][8] In the case of Caldwell v. Texas, Chief Justice Melville Fuller wrote on behalf of a unanimous Court as follows, regarding the Fourteenth Amendment: "the powers of the States in dealing with crime within their borders are not limited, but no State can deprive particular persons or classes of persons of equal and impartial justice under the law."[9] The last seven words are summarized by the inscription on the U.S. Supreme Court building.[7]

Later in 1891, Fuller's opinion for the Court in Leeper v. Texas again referred to "equal...justice under...law".[10] Like Caldwell, the Leeper opinion was unanimous, in contrast to the Fuller Court's major disagreements about equality issues in other cases such as Plessy v. Ferguson.[11]

In both Caldwell and Leeper, murder indictments were challenged because they allegedly gave inadequate notice of the crimes being charged. The Court upheld the indictments because they followed the form required by Texas law.[12] In a case nine years later (Maxwell v. Dow), the Court quoted the "equal...justice under...law" phrase that it had used in Caldwell and Leeper, to make the point that Utah could devise its own criminal procedure, as long as defendants are "proceeded against by the same kind of procedure and ... have the same kind of trial, and the equal protection of the laws is secured to them."[13]

In the 1908 case of Ughbanks v. Armstrong, the Fuller Court yet again discussed the Fourteenth Amendment in similar terms, but this time mentioning punishments: "The last-named Amendment was not intended to, and does not, limit the powers of a State in dealing with crime committed within its own borders or with the punishment thereof, although no State can deprive particular persons or classes of persons of equal and impartial justice under the law."[14]

Ughbanks was a burglary case, and the opinion was written for the Court by Justice Rufus Peckham, while Justice John Marshall Harlan was the sole dissenter. The Court would later reject the idea that the Fourteenth Amendment does not limit punishments (see the 1962 case of Robinson v. California).

In the years since moving into their present building, the Supreme Court has often connected the words "equal justice under law" with the Fourteenth Amendment. For example, in the 1958 case of Cooper v. Aaron, the Court said: "The Constitution created a government dedicated to equal justice under law. The Fourteenth Amendment embodied and emphasized that ideal."[15][16]

The words "equal justice under law" are not in the Constitution, which instead says that no state shall "deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws."[17] From an architectural perspective, the main advantage of the former over the latter was brevity — the Equal Protection Clause was not short enough to fit on the pediment given the size of the letters to be used.

Following ancient tradition

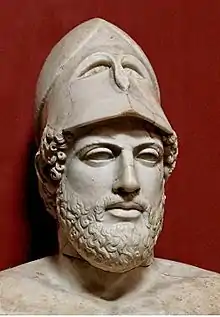

In the funeral oration that he delivered in 431 BC, the Athenian leader Pericles encouraged belief in what we now call equal justice under law.[18] Thus, when Chief Justice Fuller wrote his opinion in Caldwell v. Texas, he was by no means the first to discuss this concept.[19] There are several different English translations of the relevant passage in Pericles' funeral oration.

Here is Pericles discussing "equal justice" according to the English translation by Richard Crawley in 1874:

Our constitution does not copy the laws of neighbouring states; we are rather a pattern to others than imitators ourselves. Its administration favours the many instead of the few; this is why it is called a democracy. If we look to the laws, they afford equal justice to all in their private differences; if no social standing, advancement in public life falls to reputation for capacity, class considerations not being allowed to interfere with merit; nor again does poverty bar the way, if a man is able to serve the state, he is not hindered by the obscurity of his condition.[20]

The English translation by Benjamin Jowett in 1881 likewise had Pericles saying: "the law secures equal justice to all alike in their private disputes".[21] And, the English translation by Rex Warner in 1954 had Pericles saying: "there exists equal justice to all and alike in their private disputes".[22] The funeral oration by Pericles was published in Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, of which there are several other English translations.

As quoted above, Pericles said that a person's wealth or prominence should not influence his eligibility for public employment or affect the justice he receives. Similarly, Chief Justice Hughes defended the inscription "equal justice under law" by referring to the judicial oath of office, which requires judges to "administer justice without respect to persons, and do equal right to the poor and to the rich".[3] Decades later, Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall made a similar point: "The principles which would have governed with $10,000 at stake should also govern when thousands have become billions. That is the essence of equal justice under law."[23][24]

See also

References

- Pusey, Merlo. Charles Evans Hughes, Volume 2, p. 689 (Columbia University Press 1963).

- West Pediment Information Sheet via U.S. Supreme Court web site. At that time, the other members of the Commission were Senator Henry W. Keyes, Senator James A. Reed, Representative Richard N. Elliott, Representative Fritz G. Lanham, and Architect of the Capitol David Lynn. See Liu, Honxia. "Court Gazing: Features of Diversity in the Supreme Court Building", Court Review (Winter 2004)

- McGurn, Barrett. "Slogans to Fit the Occasion", pp. 170-174, United States Supreme Court Yearbook (1982).

- Goodwin, Priscilla. "A Closer Look at the Bronze Courtroom Gates", Supreme Court Quarterly, Vol. 9, p. 8 (1988).

- Chen, Jim. "Come Back to the Nickel and Five: Tracing the Warren Court's Pursuit of Equal Justice Under Law", Washington and Lee Law Review, Vol. 59, pp. 1305-1306 (2002).

- Ball, Milner. Lying Down Together: Law, Metaphor and Theology, p. 23 (Univ. of Wisconsin Press 1985).

- Cabraser, Elizabeth. "The Essentials of Democratic Mass Litigation", Columbia Journal of Law & Social Problems, Vol. 45, p. 499, 500 (Summer 2012).

- Peccarelli, Anthony. "The Meaning of Justice", DuPage County Bar Association Brief (March 2000), via Archive.org.

- Caldwell v. Texas, 137 U.S. 692 (1891).

- Leeper v. Texas, 139 U.S. 462 (1891). Fuller's opinion in Leeper stated: "It must be regarded as settled that....by the Fourteenth Amendment the powers of States in dealing with crime within their borders are not limited, except that no State can deprive particular persons, or classes of persons, of equal and impartial justice under the law; that law in its regular course of administration through courts of justice is due process, and when secured by the law of the State the constitutional requirement is satisfied; and that due process is so secured by laws operating on all alike, and not subjecting the individual to the arbitrary exercise of the powers of government unrestrained by the established principles of private right and distributive justice."

- Aside from Fuller, the members of the Court in 1891 were as follows: Joseph P. Bradley, Stephen Johnson Field, John Marshall Harlan, Horace Gray, Samuel Blatchford, Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar, David Josiah Brewer, and Henry Billings Brown. The Fuller Court most famously disagreed about equality issues in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896).

- Stuntz, William. The Collapse of American Criminal Justice, p. 124 (Harvard U. Press 2011).

- Maxwell v. Dow, 176 U.S. 581 (1900); Justice Peckham wrote the Court's opinion, and Justice Harlan was the sole dissenter. Harlan argued that a person cannot be tried for an infamous crime by a jury of less than twelve persons, instead of the eight jurors allowed in Utah. Many years later, in Williams v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78 (1970), the Court held that six jurors are enough.

- Ughbanks v. Armstrong, 208 U.S. 481 (1908).

- Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958).

- Mack, Raneta and Kelly, Michael. Equal Justice in the Balance: America's Legal Responses to the Emerging Terrorist Threat, p. 16 (U. Mich. Press 2004).

- Feldman, Noah. Scorpions: The Battles and Triumphs of FDR's Great Supreme Court Justices, p. 145 (Hachette Digital 2010).

- Rice, George. Law for the Public Speaker: Legal Aspects of Public Address, p. 171 (Christopher Pub. House, 1958).

- See, e.g., Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886): "Though the law itself be fair on its face and impartial in appearance, yet, if it is applied and administered by public authority with an evil eye and an unequal hand, so as practically to make unjust and illegal discriminations between persons in similar circumstances, material to their rights, the denial of equal justice is still within the prohibition of the Constitution."

- Thucydides, The History of the Peloponnesian War, Written 431 B.C.E, Translated by Richard Crawley (1874), retrieved via Project Gutenberg.

- Jowett, Benjamin. Thucydides, translated into English, to which is prefixed an essay on inscriptions and a note on the geography of Thucydides, Archived 2016-06-07 at the Wayback Machine Second edition, Oxford, Clarendon Press (1900): "Our form of government does not enter into rivalry with the institutions of others. We do not copy our neighbours, but are an example to them. It is true that we are called a democracy, for the administration is in the hands of the many and not of the few. But while the law secures equal justice to all alike in their private disputes, the claim of excellence is also recognised; and when a citizen is in any way distinguished, he is preferred to the public service, not as a matter of privilege, but as the reward of merit. Neither is poverty a bar, but a man may benefit his country whatever be the obscurity of his condition."

- Pericles's Funeral Oration, translated by Rex Warner (1954), via wikisource: "Our form of government does not enter into rivalry with the institutions of others. Our government does not copy our neighbors', but is an example to them. It is true that we are called a democracy, for the administration is in the hands of the many and not of the few. But while there exists equal justice to all and alike in their private disputes, the claim of excellence is also recognized; and when a citizen is in any way distinguished, he is preferred to the public service, not as a matter of privilege, but as the reward of merit. Neither is poverty an obstacle, but a man may benefit his country whatever the obscurity of his condition."

- Pennzoil v. Texaco, 481 U.S. 1 (1987)(Thurgood Marshall, concurring in the judgment).

- "How To Handle A Texas-sized Lawsuit", Chicago Tribune (April 11, 1987).

External links

Statue of Thurgood Marshall featuring "Equal Justice Under Law".