Catholic bishops in Nazi Germany

Catholic bishops in Nazi Germany differed in their responses to the rise of Nazi Germany, World War II, and the Holocaust during the years 1933–1945. In the 1930s, the Episcopate of the Catholic Church of Germany comprised 6 Archbishops and 19 bishops while German Catholics comprised around one third of the population of Germany served by 20,000 priests.[1][2] In the lead up to the 1933 Nazi takeover, German Catholic leaders were outspoken in their criticism of Nazism. Following the Nazi takeover, the Catholic Church sought an accord with the Government, was pressured to conform, and faced persecution. The regime had flagrant disregard for the Reich concordat with the Holy See, and the episcopate had various disagreements with the Nazi government, but it never declared an official sanction of the various attempts to overthrow the Hitler regime.[3] Ian Kershaw wrote that the churches "engaged in a bitter war of attrition with the regime, receiving the demonstrative backing of millions of churchgoers. Applause for Church leaders whenever they appeared in public, swollen attendances at events such as Corpus Christi Day processions, and packed church services were outward signs of the struggle of ... especially of the Catholic Church - against Nazi oppression". While the Church ultimately failed to protect its youth organisations and schools, it did have some successes in mobilizing public opinion to alter government policies.[4]

The German bishops initially hoped for a quid pro quo that would protect Catholic schools, organisations, publications and religious observance.[5] While head of the Bishop's Conference Adolf Bertram persisted in a policy of avoiding confrontation on broader issues of human rights, the activities of Bishops such as Konrad von Preysing, Joseph Frings and Clemens August Graf von Galen came to form a coherent, systematic critique of many of the teachings of Nazism.[6] Kershaw wrote that, while the "detestation of Nazism was overwhelming within the Catholic Church", it did not preclude church leaders approving of areas of the regime's policies, particularly where Nazism "blended into 'mainstream' national aspirations"—like support for "patriotic" foreign policy or war aims, obedience to state authority (where this did not contravene divine law); and destruction of atheistic Marxism and Soviet Bolshevism - and traditional Christian anti-Judaism was "no bulwark" against Nazi biological antisemitism.[7] Such protests as the bishops did make about the mistreatment of the Jews tended to be by way of private letters to government ministers, rather than explicit public pronouncements.[4] From the outset, Pope Pius XI, had ordered the Papal Nuncio in Berlin, Cesare Orsenigo, to "look into whether and how it may be possible to become involved" in the aid of Jews, but Orsenigo proved a poor instrument in this regard, concerned more with the anti-church policies of the Nazis and how these might effect German Catholics, than with taking action to help German Jews.[8]

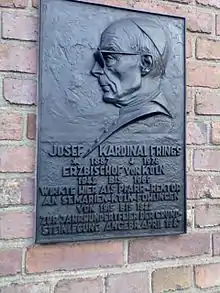

By 1937, after four years of persecution, the church hierarchy, which had initially sought to co-operate with the new government, had become highly disillusioned and Pope Pius XI issued the Mit brennender Sorge anti-Nazi encyclical, which had been co-drafted by Cardinal Archbishop Michael von Faulhaber of Munich together, with Preysing and Galen and the Vatican Sectretary of State Cardinal Pacelli (the future Pope Pius XII). The encyclical accused the Nazis of sowing "secret and open fundamental hostility to Christ and His Church". The German Bishops condemned the Nazi sterilization law. In 1941, Bishop Clemens von Galen led protests against the Nazi euthanasia programme. In 1941, a pastoral letter of the German Bishops proclaimed that "the existence of Christianity in Germany is at stake", and a 1942 letter accused the government of "unjust oppression and hated struggle against Christianity and the Church". At the close of the war, the resistor Joseph Frings, succeeded the appeaser Adolf Bertram as chairman of the Fulda Bishops' Conference, and, along with Galen and Preysing, was promoted to Cardinal by Pius XII.

The Anschluss with Austria increased the number and percentage of Catholics within the Reich. A pattern of attempted co-operation, followed by repression was repeated. At the direction of Cardinal Innitzer, the churches of Vienna pealed their bells and flew swastikas for Hitler's arrival in the city on 14 March 1938.[9] However, wrote Mark Mazower, such gestures of accommodation were "not enough to assuage the Austrian Nazi radicals, foremost among them the young Gauleiter Globocnik".[10] Globocnik launched a crusade against the Church, and the Nazis confiscated property, closed Catholic organisations and sent many priests to Dachau.[10] A Nazi mob ransacked Cardinal Innitzer's residence, after he had denounced Nazi persecution of the Church.[11] In the Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, the Church faced its most extreme persecution. But after the invasion, Nuncio Orsenigo in Berlin assumed the role of protector of the Church in the annexed regions, in conflict with his role of facilitating better relations with the German government, and his own fascistic sympathies.[12] In 1939, five of the Polish bishops of the annexed Warthegau region were deported to concentration camps.[13] In Greater Germany through the Nazi period, just one German Catholic bishop was briefly imprisoned in a concentration camp, and just one other expelled from his diocese.[14]

List

Years in parentheses are the years of their episcopate.

- Wilhelm Berning, bishop of Osnabrück (1914–1955)

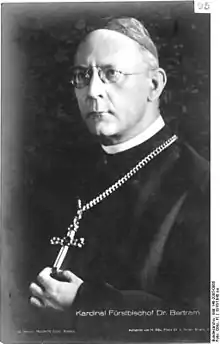

- Cardinal Adolf Bertram, archbishop of Breslau, ex officio head of the German episcopate (1914–1945)

- Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber, archbishop of Munich (1917–1952)

- Josef Frings, archbishop of Cologne (1942–1969)

- Clemens August Graf von Galen, bishop of Munster (1933–1946)

- Conrad Gröber, archbishop of Freiburg (1932–1948)

- Jacobus von Hauck, archbishop of Bamberg (1912–1943)

- Caspar Klein, archbishop of Paderborn (1920–1941)

- Johannes Dietz, bishop of Fulda (1939–1958)

- Petrus Legge, bishop of Dresden-Meissen (1932–1951)

- Cardinal Karl Joseph Schulte, archbishop of Cologne (1920–1941)

- Konrad von Preysing, bishop of Berlin (1935–1950)

Non-residential

- Cesare Orsenigo, nuncio to Germany (1930–1945)

Relations with the Nazi regime

The German Episcopate had various disagreements with the Nazi government, but it never declared an official sanction of the various attempts to overthrow the Hitler regime. The Vatican too persisted in seeking to maintain a "legal modus vivendi" with the regime.[3] Thus when Bishop Clemens August Graf von Galen of Münster delivered his famous 1941 denunciations of Nazi euthanasia and the lawlessness of the Gestapo, he also said that the church had never sought the overthrow of the regime.[3] Cardinal Bertram, head of the German Catholic Bishops Conference, "developed an ineffectual protest system" to satisfy the demands of other bishops, without annoying the regime.[15] On 10 August 1940, the president of the Bishops Conference on the one hand begged Hitler to resist influences hostile to Christianity - but at the same time assured the Führer of his "loyalty to the state as it is".[16]

Only gradually did Catholic resistance from the hierarchy re-emerge, in the form of the efforts of individual clerics, including Cardinal Preysing of Berlin, Bishop Galen of Münster, and Bishop Grober of Freiberg. The regime responded with arrests, the withdrawal of teaching privileges, and the seizure of church publishing houses.[15] Pastoral letters of 1942 and 1943 denounced government breaches of the Concordat and declared support for human rights and rule of law.

Kershaw wrote that, while the "detestation of Nazism was overwhelming within the Catholic Church", it did not preclude church leaders approving of areas of the regime's policies, particularly where Nazism "blended into 'mainstream' national aspirations" - like support for "patriotic" foreign policy or war aims, obedience to state authority (where this did not contravene divine law); and destruction of atheistic Marxism and Soviet Bolshevism. Traditional Christian anti-Judaism was "no bulwark" against Nazi biological antisemitism, wrote Kershaw, and on these issues "the churches as institutions felt on uncertain grounds". Opposition was generally left to fragmented and largely individual efforts.[7] Yet from the early stages of Nazism, Nazi ideology and Catholic doctrine clashed - from Alfred Rosenberg's anti-Catholic stance in The Myth of the Twentieth Century, to the Nazi sterilization and euthanasia programs. The Nazis also moved early against the church's organisational interests - attacking Political Catholicism, Catholic schools and the Catholic press.[17] Against these things, church leaders mounted vigorous defences.

- Preysing

Bishop von Preysing was among the most firm and consistent bishops to oppose the Nazis. Preysing served as Bishop of Eichstatt from 1932 to 1935 and in 1935 was appointed as Bishop of Berlin - the capital of Nazi Germany. Preysing was loathed by Hitler, who said "the foulest of carrion are those who come clothed in the cloak of humility and the foulest of these Count Presying! What a beast!".[18] He spoke out in public sermons and argued the case for firm opposition at bishops' conferences. Bishop von Preysing was one of the Catholic contacts of the Kreisau Circle of the German Resistance.[19] His Advent Pastoral Letters of 1942 and 1943 on the nature of human rights reflected the anti-Nazi theology of the Barmen Declaration of the Confessing Church, leading one to be broadcast in German by the BBC. In 1944, Preysing met with and gave a blessing to Claus von Stauffenberg, in the lead up to the July Plot to assassinate Hitler, and spoke with the resistance leader on whether the need for radical change could justify tyrannicide.[20]

- Galen

The Bishop of Münster, Clemens August Graf von Galen was Preysing's cousin.[21] In response to Nazi Ideologist Alfred RosenbergThe Myth of the Twentieth Century, Galen derided the neo-pagan theories of Rosenberg as perhaps no more than "an occasion for laughter in the educated world", but warned that "his immense importance lies in the acceptance of his basic notions as the authentic philosophy of National Socialism and in his almost unlimited power in the field of German education. Herr Rosenberg must be taken seriously if the German situation is to be understood."[22] Often Galen directly protested to Hitler over violations of the Concordat. When in 1936, Nazis removed crucifixes in schools, protest by Galen led to public demonstration. Like Presying, he assisted with the drafting of the 1937 papal encyclical.[21] He denounced the lawlessness of the Gestapo, the confiscations of church properties and the cruel program of Nazi euthanasia.[23] He attacked the Gestapo for seizing church properties and converting them to their own purposes - including use as cinemas and brothels. His three powerful sermons of July and August 1941 earned him the nickname of the "Lion of Munster".[24] Documents suggest the Nazis intended to hang Galen at the end of the war.[23] The Nazi press called him "enemy number one", Hitler called him a "liar and a traitor", and Göring said he was a "saboteur and agitator" and those who published the text of his sermons were attached - but the regime did not have him arrested.[16]

- Faulhaber

Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber was an early and prominent critic of the Nazi movement.[25] Soon after the Nazi takeover, his three Advent sermons of 1933, entitled Judaism, Christianity, and Germany, affirmed the Jewish origins of the Christian religion, the continuity of the Old and New Testaments of the Bible, and the importance of the Christian tradition to Germany. According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, "Throughout his sermons until the collapse (1945) of the Third Reich, Faulhaber vigorously criticized Nazism, despite governmental opposition. Attempts on his life were made in 1934 and in 1938. He worked with American occupation forces after the war, and received the West German Republic's highest award, the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit.[25] On November 4, 1936, Hitler and Faulhaber met. Faulhaber told Hitler that the Nazi government had been waging war on the church for three years and that the church must be free to criticize the government "when your officials or your laws offend Church dogma or the laws of morality".[26]

- Bertram

Cardinal Adolf Bertram ex officio head of the German episcopate sent Hitler birthday greetings in 1939 in the name of all German Catholic bishops, an act that angered bishop Konrad von Preysing.[27] Bertram was the leading advocate of accommodation as well as the leader of the German church, a combination that reined in other would-be opponents of Nazism.[27]

The Church Struggle

The Nazis disliked universities, intellectuals and the Catholic and Protestant churches. According to Gill, their long term plan was to "de-Christianise Germany after the final victory". The Nazis co-opted the term Gleichschaltung to mean conformity and subservience to the National Socialist German Workers' Party line: "there was to be no law but Hitler, and ultimately no god but Hitler".[29] The Kirchenkampf (Church struggle) saw the Nazis attempt to control the religious confessions of Germany. Aggressive anti-Church radicals like Joseph Goebbels and Martin Bormann saw the conflict with the Churches as a priority concern, and anti-church and anti-clerical sentiments were strong among grassroots party activists.[28] Hitler too disdained Christianity.[30] According to Kershaw, the German church leadership expended considerable energies in opposing government interference in the church and "attempts to ride roughshod over Christian doctrine and values".[4] While offering "something less than fundamental resistance to Nazism", church leaders "engaged in a bitter war of attrition with the regime".[4]

A threatening, though initially mainly sporadic persecution of the Catholic Church in Germany followed the Nazi takeover.[33] The Reichskonkordat between Germany and the Vatican was signed at the Vatican on 20 July 1933. Within three months of the signing of the document, Cardinal Bertram, head of the German Catholic Bishops Conference, was writing in a Pastoral Letter of "grievous and gnawing anxiety" with regard to the government's actions towards Catholic organisations, charitable institutions, youth groups, press, Catholic Action and the mistreatment of Catholics for their political beliefs.[34]

Prior to 1933, the Church had been quite hostile to Nazism and "its bishops energetically denounced the 'false doctrines' of the Nazis", however its opposition weakened considerably after the Concordat. Cardinal Bertram "developed an ineffectual protest system" so satisfy the demands of other bishops, without annoying the regime. Only gradually did Catholic resistance from the hierarchy re-emerge, in the form of the efforts of individual clerics, including Cardinal Preysing of Berlin, Bishop Galen of Münster, and Bishop Grober of Freiberg. The regime responded with arrests, the withdrawal of teaching privileges, and the seizure of church publishing houses.[15]

The Concordat, wrote William Shirer, "was hardly put to paper before it was being broken by the Nazi Government". On 25 July, the Nazis promulgated their sterilization law, an offensive policy in the eyes of the Catholic Church. Five days later, moves began to dissolve the Catholic Youth League. Clergy, nuns and lay leaders began to be targeted, leading to thousands of arrests over the ensuing years, often on trumped up charges of currency smuggling or "immorality".[35] In effort to counter the strength and influence of spiritual resistance, the security services monitored the activities of the bishops very closely - instructing that agents be set up in every diocese, that the bishops' reports to the Vatican should be obtained and that the bishops' areas of activity must be found out. Deans were to be targeted as the "eyes and ears of the bishops" and a "vast network" established to monitor the activities of ordinary clergy: "The importance of this enemy is such that inspectors of security police and of the security service will make this group of people and the questions discussed by them their special concern".[36]

In January 1934, Hitler appointed Alfred Rosenberg as the cultural and educational leader of the Reich. Rosenberg was a neo-pagan and notoriously anti-Catholic.[32][34] In his "Myth of the Twentieth Century" (1930), Rosenberg had described the Catholic Church as one of the main enemies of Nazism.[31] Bishop von Galen derided the neo-pagan theories of Rosenberg as perhaps no more than "an occasion for laughter in the educated world", but warned that "his immense importance lies in the acceptance of his basic notions as the authentic philosophy of National Socialism and in his almost unlimited power in the field of German education. Herr Rosenberg must be taken seriously if the German situation is to be understood."[22]

Goebbels noted the mood of Hitler in his diary on 25 October 1936: "Trials against the Catholic Church temporarily stopped. Possibly wants peace, at least temporarily. Now a battle with Bolshevism. Wants to speak with Faulhaber".[26] On November 4, 1936, Hitler met Faulhaber. Hitler spoke for the first hour, then Faulhaber told him that the Nazi government had been waging war on the church for three years - 600 religious teachers had lost their jobs in Bavaria alone - and the number was set to rise to 1700 and the government had instituted laws the Church could not accept - like the sterilization of criminals and the handicapped. While the Catholic Church respected the notion of authority, nevertheless, "when your officials or your laws offend Church dogma or the laws of morality, and in so doing offend our conscience, then we must be able to articulate this as responsible defenders of moral laws".[26] Kershaw cites the meeting as an example of Hitler's ability to "pull the wool over the eyes even of hardened critics" for "Faulhaber - a man of sharp acumen, who had often courageously criticized the Nazi attacks on the Catholic Church - went away convinced that Hitler was deeply religious".[37]

By early 1937, the German bishops, who had initially attempted to co-operate with the new government, had become highly disillusioned. In March, Pope Pius XI issued the Mit brennender Sorge (German: "With burning concern") encyclical.[38] It accused the government of "systematic hostility leveled at the Church".[39][40] Bishops Konrad von Preysing and Clemens August Graf von Galen helped draft the document.[41]

The Nazis responded with, an intensification of the Church Struggle, beginning around April.[28] Goebbels noted heightened verbal attacks on the clergy from Hitler in his diary and wrote that Hitler had approved the start of trumped up "immorality trials" against clergy and anti-Church propaganda campaign. Goebbels' orchestrated attack included a staged "morality trial" of 37 Franciscans.[28] In March 1938, Nazi Minister of State Adolf Wagner spoke of the need to continue the fight against Political Catholicism and Alfred Rosenberg said that the churches of Germany "as they exist at present, must vanish from the life of our people". In the space of a few months, Bishop Sproll of Rothenberg, Cardinal von Faulhaber of Munich and Cardinal Innitzer of Vienna were physically attacked by Nazis.[42] After initially offering support to the Anschluss, Austria's Cardinal Innitzer became a critic of the Nazis and was subject to violent intimidation from them.[43] With power secured in Austria, the Nazis repeated their persecution of the Church and in October, a Nazi mob ransacked Innitzer's residence, after he had denounced Nazi persecution of the Church.[44] On 26 July 1941, Bishop von Galen wrote to the government to complain "The Secret Police has continued to rob the property of highly respected German men and women merely because they belonged to Catholic orders".[45]

Because the Nazi Gleichschaltung policy of forced coordination encountered such forceful opposition from the churches, Hitler decided to postpone the struggle until after the war.[46] Hitler himself possessed radical instincts in relation to the continuing conflict with the Catholic and Protestant Churches in Germany. Though he occasionally spoke of wanting to delay the Church struggle and was prepared to restrain his anti-clericalism out of political considerations, his "own inflammatory comments gave his immediate underlings all the license they needed to turn up the heat in the 'Church Struggle, confident that they were 'working towards the Fuhrer'".[28]

1941 Pastoral Letter of the German Bishops

On 26 June 1941, the German Bishops drafted a pastoral letter from their Fulda Conference, to be read from all pulpits on 6 July: "Again and again have the bishops brought their justified claims and complaints before the proper authorities ... Through this pastoral declaration the Bishops want you to see the real situation of the church". The Bishops wrote that the church faced "restrictions and limitations put on the teaching of their religion and on church life" and of great obstacles in the fields of Catholic education, freedom of service and religious festivals, the practice of charity by religious orders and the role of preaching morals. Catholic presses had been silenced and kindergartens closed and religious instruction in schools nearly stamped out:[47]

Dear Members of the disoceses: We Bishops ... feel an ever great sorrow about the existence of powers working to dissolve the blessed union between Christ and the German people ... the existence of Christianity in Germany is at stake.

— Pastoral letter of the German Bishops, read on 6 July 1941

1942 Pastoral Letter of the German Bishops

The following year, on 22 March 1942, the German Bishops issued a pastoral letter on "The Struggle against Christianity and the Church":[48] The letter launched a defence of human rights and the rule of law and accused the Reich Government of "unjust oppression and hated struggle against Christianity and the Church", despite the loyalty of German Catholics to the Fatherland, and brave service of Catholics soldiers. It accused the regime of seeking to rid Germany of Christianity:[49]

For years a war has raged in our Fatherland against Christianity and the Church, and has never been conducted with such bitterness. Repeatedly the German bishops have asked the Reich Government to discontinue this fatal struggle; but unfortunately our appeals and our endeavours were without success.

— 22 March 1942 Pastoral Letter of the German Bishops

The letter outlined serial breaches of the 1933 Concordat, reiterated complaints of the suffocation of Catholic schooling, presses and hospitals and said that the "Catholic faith has been restricted to such a degree that it has disappeared almost entirely from public life" and even worship within churches in Germany "is frequently restricted or oppressed", while in the conquered territories (and even in the Old Reich), churches had been "closed by force and even used for profane purposes". The freedom of speech of clergymen had been suppressed and priests were being "watched constantly" and punished for fulfilling "priestly duties" and incarcerated in Concentration camps without legal process. Religious orders had been expelled from schools, and their properties seized, while seminaries had been confiscated "to deprive the Catholic priesthood of successors".[49]

The bishops denounced the Nazi euthanasia program and declared their support for human rights and personal freedom under God and "just laws" of all people:[49]

We demand juridical proof of all sentences and release of all fellow citizens who have been deprived of their liberty without proof ... We the German bishops shall not cease to protest against the killing of innocent persons. Nobody's life is safe unless the Commandment, "Thous shalt not kill" is observed ... We the bishops, in the name of the Catholic people ... demand the return of all unlawfully confiscated and in some cases sequestered property ... for what happens today to church property may tomorrow happen to any lawful property.

— 22 March 1942 Pastoral Letter of the German Bishops

Austria

The Anschluss saw the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany in early 1938.[50] Austria was overwhelmingly Catholic.[44] At the direction of Cardinal Innitzer, the churches of Vienna pealed their bells and flew swastikas for Hitler's arrival in the city on 14 March.[9] However, wrote Mark Mazower, such gestures of accommodation were "not enough to assuage the Austrian Nazi radicals, foremost among them the young Gauleiter Globocnik".[10] Globocnik launched a crusade against the Church, and the Nazis confiscated property, closed Catholic organisations and sent many priests to Dachau.[10]

Anger at the treatment of the Church in Austria grew quickly and October 1938, wrote Mazower, saw the "very first act of overt mass resistance to the new regime", when a rally of thousands left Mass in Vienna chanting "Christ is our Fuehrer", before being dispersed by police.[51] A Nazi mob ransacked Cardinal Innitzer's residence, after he had denounced Nazi persecution of the Church.[44] L'Osservatore Romano reported on 15 October that Hitler Youth and the SA had gathered at Innitzer's Cathedral during a service for Catholic Youth and started "counter-shouts and whistlings: 'Down with Innitzer! Our faith is Germany'". The following day, the mob stoned the Cardinal's residence, broke in and ransacked it—bashing a secretary unconscious, and storming another house of the cathedral curia and throwing its curate out the window.[42]

In a Table Talk of July 1942 discussing his problems with the Church, Hitler singles out Innitzer's early gestures of cordiality as evidence of the extreme caution with which Church diplomats must be treated: "there appeared a man who addressed me with such self-assurance and beaming countenance, just as if, throughout the whole of the Austrian Republic he had never even touched a hair of the head of any National Socialist!"[52]

Nazi euthanasia

From 1939, the regime began its program of euthanasia in Nazi Germany, in which those deemed "racially unfit" were to be "euthanased".[23] The senile, the mentally handicapped and mentally ill, epileptics, cripples, children with Down Syndrome and people with similar afflictions were all to be killed.[24] The program involved the systematic murder of more than 70,000 people.[23]

The Papacy and German bishops had already protested against the Nazi sterilization of the "racially unfit". Catholic protests against the escalation of this policy into "euthanasia" began in the summer of 1940. Despite Nazi efforts to transfer hospitals to state control, large numbers of handicapped people were still under the care of the Churches. Galen wrote to Germany's senior cleric, Cardinal Adolf Bertram, in July 1940 urging the Church take up a moral position. Bertram urged caution. Archbishop Conrad Groeber of Freiburg wrote to the head of the Reich Chancellery, and offered to pay all costs being incurred by the state for the "care of mentally people intended for death". Caritas directors sought urgent direction from the bishops, and the Fulda Bishops Conference sent a protest letter to the Reich Chancellery on 11 August, then sent Bishop Heinrich Wienken of Caritas to discuss the matter. Wienken cited the commandment "thous shalt not kill" to officials and warned them to halt the program or face public protest from the Church. Wienken subsequently wavered, fearing a firm line might jeopardise his efforts to have Catholic priests released from Dachau, but was urged to stand firm by Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber. The government refused to give a written undertaking to halt the program, and the Vatican declared on 2 December that the policy was contrary to natural and positive Divine law: "The direct killing of an innocent person because of mental or physical defects is not allowed".[54]

Bishop von Galen had the decree printed in his newspaper on 9 March 1941. Subsequent arrests of priests and seizure of Jesuit properties by the Gestapo in his home city of Munster, convinced Galen that the caution advised by his superior had become pointless. On 6, 13 and 20 July 1941, Galen spoke against the seizure of properties, and expulsions of nuns, monks and religious and criticised the euthanasia programme. In an attempt to cow Galen, the police raided his sister's convent, and detained her in the cellar. She escaped the confinement, and Galen, who had also received news of the imminent removal of further patients, launched his most audacious challenge on the regime in a 3 August sermon. He declared the murders to be illegal, and said that he had formally accused those responsible for murders in his diocese in a letter to the public prosecutor. The policy opened the way to the murder of all "unproductive people", like old horses or cows, including invalid war veterans: "Who can trust his doctor anymore?", he asked. He declared, wrote Evans, that Catholics must "avoid those who blasphemed, attacked their religion, or brought about the death of innocent men and women. Otherwise they would become involved in their guilt".[55] Galen said that it was the duty of Christians to resist the taking of human life, even if it meant losing their own lives.[23]

"The sensation created by the sermons", wrote Richard J. Evans, "was enormous".[56] Kershaw characterised Von Galen's 1941 "open attack" on the government's euthanasia program as a "vigorous denunciation of Nazi inhumanity and barbarism".[4] According to Gill, "Galen used his condemnation of this appalling policy to draw wider conclusions about the nature of the Nazi state.[24] He spoke of a moral danger to Germany from the regime's violations of basic human rights.[57] Galen had the sermons read in parish churches. The British broadcast excerpts over the BBC German service, dropped leaflets over Germany, and distributed the sermons in occupied countries.[56]

Bishop Antonius Hilfrich of Limburg wrote to the Justice Minister, denouncing the murders. Bishop Albert Stohr of Mainz condemned the taking of life from the pulpit. Some of the priests who distributed the sermons were among those arrested and sent to the concentration camps amid the public reaction to the sermons.[56] Hitler wanted to have Galen removed, but Goebbels told him this would result in the loss of the loyalty of Westphalia.[24] The regional Nazi leader, and Hitler's deputy Martin Bormann called for Galen to be hanged, but Hitler and Goebbels urged a delay in retribution till war's end.[58]

The Catholic bishops jointly expressed their "horror" at the policy in their 1942 Pastoral Letter:[49]

Every man has the natural right to life and the goods essential for living. The living God, the Creator of all life, is sole master over life and death. With deep horror Christian Germans have learned that, by order of the State authorities, numerous insane persons, entrusted to asylums and institutions, were destroyed as so-called "unproductive citizens." At present a large-scale campaign is being made for the killing of incurables through a film recommended by the authorities and designed to calm the conscience through appeals to pity. We German Bishops shall not cease to protest against the killing of innocent persons. Nobody's life is safe unless the Commandment, "Thou shalt not kill," is observed.

— German Bishops' Pastoral Letter of 22 March 1942

Under pressure from growing protests, Hitler halted the main euthanasia program on 24 August 1941, though less systematic murder of the handicapped continued.[59] While Galen survived, Bishop von Preysing's Cathedral Administrator, Fr Bernhard Lichtenberg met his demise for protesting directly to Dr Conti, the Nazi State Medical Director. He was arrested soon after and later died en route to Dachau.[60] Some of the priests who distributed the sermons were among those arrested and sent to the concentration camps amid the public reaction to the sermons.[56]

The Holocaust

Knowledge of

According to historians David Bankier and Hans Mommsen a through knowledge of the Holocaust was well within the reach of the German bishops, if they wanted to find out.[61] According to historian Michael Phayer, "a number of bishops did want to know, and they succeeded very early on in discovering what their government was doing to the Jews in occupied Poland".[62] Wilhelm Berning, for example, knew about the systematic nature of the Holocaust as early as February 1942, only one month after the Wannsee Conference.[62] Most German Church historians believe that the church leaders knew of the Holocaust by the end of 1942, knowing more than any other church leaders outside the Vatican.[63]

However, after the war, some bishops, including Adolf Bertram and Conrad Grober claimed that they were not aware of the extent and details of the Holocaust, and were not certain of the information they did possess.[63]

Public statements

Bishops von Preysing and Frings were the most public in the statements against genocide.[64] According to Phayer, "no other German bishops spoke as pointedly as Preysing and Frings".[64]

Fulda meetings

The bishops met annually during the war in Fulda.[27]

The issue of whether the bishops should speak out against the persecution of the Jews was debated at a 1942 meeting in Fulda.[65] The consensus was to "give up heroic action in favor of small successes".[65] A draft letter proposed by Margarete Sommer was rejected, because it was viewed as a violation of the Reichskonkordat to speak out on issues not directly related to the church.[65]

In 1943, bishop Grober expressed the opinion that the bishop should remain loyal to the "beloved folk and Fatherland", despite abuses of the Reichskonkordat.[27]

Defence of Jews

What protests the German bishops did make regarding anti-Jewish policies, tended to be by way of private letters to government ministers.[4] Traditional Christian anti-Judaism was "no bulwark" against Nazi biological antisemitism, wrote Kershaw, and on these issues opposition was generally left to fragmented and largely individual efforts.[7] Bishops Konrad von Preysing and Clemens August Graf von Galen assisted with the drafting of Pope Pius XI's 1937 German encyclical Mit brennender Sorge, which was written partly in response to the Nuremberg Laws.[41][66] The papal letter condemned racial theories and the mistreatment of people based on race.[66] According to Gill, "Hitler was beside himself with rage. Twelve presses were seized, and hundreds of people sent either to prison or the camps".[38] This despite Article 4 of the reichskonkordat guaranteeing freedom of correspondence between the Vatican and the German clergy,[67] Later, in Pius XII's first encyclical, Summi Pontificatus, which came only a month into the war, the Church reiterated the Catholic stance against racism and anti-semitism: "there is neither Gentile nor Jew, circumcision nor uncircumcision, barbarian nor Scythian, bond nor free. But Christ is all and in all" and endorsed resistance against those opposed to the ethical content of "the Revelation on Sinai" (the Ten Commandments given to Moses) and the Sermon on the Mount given by Jesus.[68]

When the newly installed Nazi Government began to instigate its program of anti-semitism, Pope Pius XI, through his Secretary of State Cardinal Pacelli, ordered the Papal Nuncio in Berlin, Cesare Orsenigo, to "look into whether and how it may be possible to become involved" in their aid. Orsenigo proved a poor instrument in this regard, concerned more with the anti-church policies of the Nazis and how these might effect German Catholics, than with taking action to help German Jews. Cardinal Innitzer called him timid and ineffectual with respect to the worsening situation for German Jewry.[8]

Nazi racial ideology held that Jews were subhuman and posited that Christ had been an Aryan. Ludwig Muller was Hitler's choice for Reich Bishop of the German Evangelical Church, which sought to subordinate German Protestantism to the Nazi Government.[69] But Muller's heretical views against St Paul and the Semitic origins of Christ and the Bible quickly alienated sections of the Protestant church, leading to the foundation of the Confessing Church.[70] The attack on the Biblical origins of Christianity also alarmed Catholics. Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber responded with three Advent sermons in 1933, entitled Judaism, Christianity, and Germany, He affirmed the Jewish origins of the Christian religion, the continuity of the Old and New Testaments of the Bible, and the importance of the Christian tradition to Germany.[25]

According to Michael Phayer, Bishops Konrad von Preysing and Joseph Frings were the most outspoken against Nazi mistreatment of the Jews.[64] While Preysing was protected from Nazi retaliation by his position, his cathedral administrator Bernard Lichtenberg, was not. Lichtenberg served at St. Hedwig's Cathedral from 1932, and was under the watch of the Gestapo by 1933. He ran Preysing's aid unit (the Hilfswerke beim Bischöflichen Ordinariat Berlin) which secretly assistance to those who were being persecuted by the regime. From 1938, Lichtenberg conducted prayers for the Jews and other inmates of the concentration camps, including "my fellow priests there". For preaching against Nazi propaganda and writing a letter of protest concerning Nazi euthanasia, he was arrested in 1941, and died en route to Dachau Concentration Camp in 1943.[24]

Gorsky wrote that "The Vatican endeavored to find places of refuge for Jews after Kristallnacht in November 1938, and the Pope instructed local bishops to help all who were in need at the beginning of the war."[71] In 1943, the German bishops debated whether to directly confront Hitler collectively over what they knew of the murdering of Jews, but decided not to take this course. Some bishops did speak out individually however - Von Preysing of Berlin spoke of a right of all people to life, Joseph Frings of Cologne wrote a pastoral letter cautioning his diocese not, even in wartime, to violate the inherent rights of others to life, even those "not of our blood" and preached in a sermon that "no one may take the property or life of an innocent person just because he is a member of a foreign race".[72]

Historical evaluation

Praise

Some German bishops are praised for their wartime actions. According to Phayer, "several bishops did speak out".[61] Heinrich Wienken (a post-war bishop) very likely personally hid Jews in Berlin during the war.[27] Clemens August Graf von Galen was a well-known public opponent of the Nazi "euthanasia" program, if not the Holocaust itself.[61]

Criticism

Phayer believes that the German episcopate—as opposed to other bishops—could have done more to save Jews.[61] According to Phayer, "had the German bishops confronted the Holocaust publicly and nationally, the possibilities of undermining Hitler's death apparatus might have existed. Admittedly, it is speculative to assert this, but it is certain that many more German Catholics would have sought to save Jews by hiding them if their church leaders had spoken out".[61] In this regard, Phayer places the responsibility with the Vatican, asserting that "a strong papal assertion would have enabled the bishops to overcome their disinclinations" and that "Bishop Preysing's only hope to spur his colleagues into action lay in Pope Pius XII".[62]

See also

- Catholic resistance to Nazi Germany

- Index of Vatican City-related articles

- International Catholic-Jewish Historical Commission

- Nazi persecution of the Catholic Church

- Pope Benedict XV and Judaism

- Pope Benedict XVI and Judaism

- Pope Francis and Judaism

- Pope John Paul II and Judaism

- Pope Pius XII and the Holocaust

- Pontifical Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews

- Relations between Catholicism and Judaism

- Rescue of Jews by Catholics during the Holocaust

Notes

- "The German Churches and the Nazi State". Holocaust Encyclopedia (online ed.). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 2 July 2016.

- Lewy, Gunther (1964). The Catholic Church and Nazi Germany (first ed.). Da Capo. pp. 342–345.

- Wolf (1970), p. 225.

- Kershaw (2000), pp. 210–211.

- Hamerow (1997), p. 199.

- Hamerow (1997), p. 133.

- Kershaw (2000), pp. 211–212.

- O'Shea, Paul Damian (2008). A Cross Too Heavy: Eugenio Pacelli: Politics and the Jews of Europe, 1917-1943. Rosenberg. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-877058-71-4.

- Kershaw (2008), p. 413.

- Mazower (2008), pp. 51-52.

- Shirer (2011), pp. 349-350.

- Garliński, Józef (1987). Poland in the Second World War. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-1-349-09910-8.

- Craughwell, Thomas J. (Summer 1998). "The Gentile Holocaust". CatholicCulture.org.

- Hamerow (1997), pp. 196-197.

- Fest (1996), p. 31.

- Berben (1975), p. 141.

- Wolf (1970), p. 224.

- Bonney (2009), pp. 29–30.

- Gill (1994), p. 161.

- Gill (1994), pp. 58-59.

- Gill (1994), p. 59.

- Bonney (2009), p. 128.

- "Blessed Clemens August, Graf von Galen". Encyclopædia Britannica (online ed.). Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- Gill (1994), p. 60.

- "Michael von Faulhaber". Encyclopædia Britannica (online ed.). Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- Bonney (2009), p. 122.

- Phayer (2000), p. 75.

- Kershaw (2008), pp. 381-382.

- Gill (1994), pp. 14–15.

- Alan Bullock; Hitler, a Study in Tyranny; HarperPerennial Edition 1991; p218

- "Alfred Rosenberg". Encyclopædia Britannica (online ed.). Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- Shirer (2011), p. 240.

- Kershaw (2008), p. 332.

- National Catholic Welfare Conference (1942).

- Shirer (2011), p. 234–235.

- Berben (1975), pp. 141-142.

- Kershaw (2008), p. 373.

- Gill (1994), p. 58.

- Shirer (2011), pp. 234-235.

- Pope Pius XI (14 March 1937). "Mit Brennender Sorge". Libreria Editrice Vaticana.

- Fest (1996), p. 59.

- National Catholic Welfare Conference (1942), pp. 29–30.

- "Theodor Innitzer". Encyclopædia Britannica (online ed.). Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- Shirer (2011), pp. 349–350.

- National Catholic Welfare Conference (1942), p. 55.

- Fest (1996), p. 32.

- National Catholic Welfare Conference (1942), pp. 63–67.

- Fest (1996), p. 377.

- National Catholic Welfare Conference (1942), pp. 74–80.

- Shirer (2011), pp. 325–329.

- Mazower (2008), p. 52.

- Hitler, Adolf (2000). Hitler's Table Talk. Translated by Cameron, Norman; Stevens, R.H. Enigma Books. p. 555. ISBN 978-1-929631-05-6.

- Gill (1994), p. 265.

- Evans (2009), pp. 95–97.

- Evans (2009), pp. 97–98.

- Evans (2009), p. 98.

- Hamerow (1997), pp. 289-290.

- Evans (2009), p. 99.

- Fulbrook, Mary (1991). Fontana History of Germany, 1918-1990: The Divided Nation. Fontana Press. pp. 104–105. ISBN 978-0-00-686111-9.

- Gill (1994), p. 61.

- Phayer (2000), p. 67.

- Phayer (2000), p. 68.

- Phayer (2000), p. 70.

- Phayer (2000), p. 77.

- Phayer (2000), p. 74.

- Coppa, Frank J. "Pius XII". Encyclopædia Britannica (online ed.). Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- National Catholic Welfare Conference (1942), p. 27.

- Pope Pius XII (20 October 1939). "Summi Pontificatus". Libreria Editrice Vaticana.

- "German Christian". Encyclopædia Britannica (online ed.). Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- Kershaw (2008), pp. 295-297.

- Gorsky, Jonathan. "Pius XII and the Holocaust" (PDF). Shoah Resource Center, The International School for Holocaust Studies.

- Phayer, Michael. "The Response of the German Catholic Church to National Socialism" (PDF). Yad Vashem. pp. 59–61.

References

- Berben, Paul (1975). Dachau, 1933-1945: the official history. London: Norfolk Press. ISBN 978-0-85211-009-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bonney, Richard, ed. (2009). Confronting the Nazi War on Christianity: The Kulturkampf Newsletters, 1936-1939. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-03911-904-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Evans, Richard J. (2009). The Third Reich at War. Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1-59420-206-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fest, Joachim C. (1996). Plotting Hitler's Death: The German Resistance to Hitler, 1933-1945. Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-7538-0040-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gill, Anton (1994). An Honourable Defeat: A History of German Resistance to Hitler, 1933-1945. H. Holt. ISBN 978-0-8050-3515-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hamerow, Theodore S. (1997). On the Road to the Wolf's Lair: German Resistance to Hitler. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-63680-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kershaw, Ian (2015) [2000]. The Nazi Dictatorship: Problems and Perspectives of Interpretation (Fourth ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4742-4094-9.

- Kershaw, Ian (2008). Hitler: A Biography. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-07562-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mazower, Mark (2008). Hitler's Empire: Nazi Rule in Occupied Europe. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-7139-9681-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- National Catholic Welfare Conference (1942). The Nazi war against the Catholic church. United States National Catholic Welfare Conference.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Phayer, Michael (2000). The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Phayer, Michael (2008). Pius XII, the Holocaust, and the Cold War. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253349309.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shirer, William L. (2011) [1959]. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-5168-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wolf, Ernst (1970). "Political and Moral Motives behind the Resistance". In Graml, Hermann; Mommsen, Hans; Reichhardt, Hans-Joachim; Wolf, Ernst (eds.). The German Resistance to Hitler. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-01662-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Lapomarda, Vincent (2012). The Catholic Bishops of Europe and the Nazi Persecutions of Catholics and Jews. The Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0-7734-2932-1. and the review of the same, Doino, William, Jr. (March 2014). "Heroes or Villains?". New Oxford Review. LXXXI (2). Archived from the original on 2016-10-11. Retrieved 2016-08-24.