Pope Pius XII

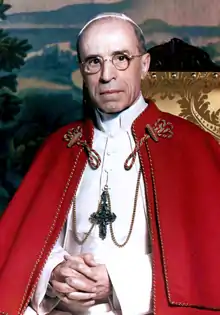

Pope Pius XII (Italian: Pio XII), born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (Italian pronunciation: [euˈdʒɛːnjo maˈriːa dʒuˈzɛppe dʒoˈvanni paˈtʃɛlli]; 2 March 1876 – 9 October 1958), was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in 1958. Before his election to the papacy, he served as secretary of the Department of Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs, papal nuncio to Germany, and Cardinal Secretary of State, in which capacity he worked to conclude treaties with European and Latin American nations, such as the Reichskonkordat with Nazi Germany.[1]

Pope Venerable Pius XII | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Rome | |

Pius XII in 1951 | |

| Diocese | Diocese of Rome |

| See | Holy See |

| Papacy began | 2 March 1939 |

| Papacy ended | 9 October 1958 |

| Predecessor | Pius XI |

| Successor | John XXIII |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 2 April 1899 by Francesco di Paola Cassetta |

| Consecration | 13 May 1917 by Benedict XV |

| Created cardinal | 16 December 1929 by Pius XI |

| Personal details | |

| Birth name | Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli |

| Born | 2 March 1876 Rome, Kingdom of Italy |

| Died | 9 October 1958 (aged 82) Castel Gandolfo, Italy |

| Previous post |

|

| Motto | Opus Justitiae Pax ("The work of justice [shall be] peace" [Is. 32: 17]) |

| Signature |  |

| Coat of arms |  |

| Sainthood | |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church |

| Title as Saint | Venerable |

| Other popes named Pius | |

Ordination history of Pope Pius XII | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

While the Vatican was officially neutral during World War II, the Reichskonkordat and his leadership of the Catholic Church during the war remain the subject of controversy—including allegations of public silence and inaction about the fate of the Jews.[2] Pius employed diplomacy to aid the victims of the Nazis during the war and, through directing the Church to provide discreet aid to Jews and others, saved hundreds of thousands of lives.[3] Pius maintained links to the German Resistance, and shared intelligence with the Allies. His strongest public condemnation of genocide was, however, considered inadequate by the Allied Powers, while the Nazis viewed him as an Allied sympathizer who had dishonoured his policy of Vatican neutrality.[4] After the war, he advocated peace and reconciliation, including lenient policies towards former Axis and Axis-satellite nations.

During his papacy, the Church issued the Decree against Communism, declaring that Catholics who profess Communist doctrine are to be excommunicated as apostates from the Christian faith. The Church experienced severe persecution and mass deportations of Catholic clergy in the Eastern Bloc. He explicitly invoked ex cathedra papal infallibility with the dogma of the Assumption of Mary in his Apostolic constitution Munificentissimus Deus.[5] His magisterium includes almost 1,000 addresses and radio broadcasts. His forty-one encyclicals include Mystici corporis, the Church as the Body of Christ; Mediator Dei on liturgy reform; and Humani generis, in which he instructed theologians to adhere to episcopal teaching and allowed that the human body might have evolved from earlier forms. He eliminated the Italian majority in the College of Cardinals in 1946.

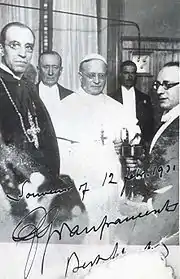

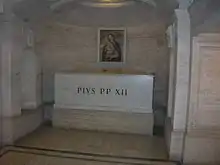

After he died in 1958, Pope Pius XII was succeeded by John XXIII. In the process toward sainthood, his cause for canonization was opened on 18 November 1965 by Paul VI during the final session of the Second Vatican Council. He was made a Servant of God by John Paul II in 1990 and Benedict XVI declared Pius XII Venerable on 19 December 2009.[6]

Early life

Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli was born on 2 March 1876 in Rome into a family of intense Catholic piety with a history of ties to the papacy (the "Black Nobility"). His parents were Filippo Pacelli (1837–1916) and Virginia (née Graziosi) Pacelli (1844–1920). His grandfather, Marcantonio Pacelli, had been Under-Secretary in the Papal Ministry of Finances[7] and then Secretary of the Interior under Pope Pius IX from 1851 to 1870 and helped found the Vatican's newspaper, L'Osservatore Romano in 1861.[8][9] His cousin, Ernesto Pacelli, was a key financial advisor to Pope Leo XIII; his father, Filippo Pacelli, a Franciscan tertiary,[10] was the dean of the Roman Rota; and his brother, Francesco Pacelli, became a lay canon lawyer and the legal advisor to Pope Pius XI, in which role he negotiated the Lateran Treaty in 1929 with Benito Mussolini, bringing an end to the Roman Question.

Together with his brother Francesco and his two sisters, Giuseppina and Elisabetta, he grew up in the Parione district in the centre of Rome. Soon after the family had moved to Via Vetrina in 1880 he began school at the convent of the French Sisters of Divine Providence in the Piazza Fiammetta. The family worshipped at Chiesa Nuova. Eugenio and the other children made their First Communion at this church and Eugenio served there as an altar boy from 1886. In 1886 too he was sent to the private school of Professor Giuseppe Marchi, close to the Piazza Venezia.[11] In 1891 Pacelli's father sent Eugenio to the Liceo Ennio Quirino Visconti Institute, a state school situated in what had been the Collegio Romano, the premier Jesuit university in Rome.

In 1894, aged 18, Pacelli began his theology studies at Rome's oldest seminary, the Almo Collegio Capranica,[12] and in November of the same year, registered to take a philosophy course at the Jesuit Pontifical Gregorian University and theology at the Pontifical Roman Athenaeum S. Apollinare. He was also enrolled at the State University, La Sapienza where he studied modern languages and history. At the end of the first academic year however, in the summer of 1895, he dropped out of both the Capranica and the Gregorian University. According to his sister Elisabetta, the food at the Capranica was to blame.[13] Having received a special dispensation he continued his studies from home and so spent most of his seminary years as an external student. In 1899 he completed his education in Sacred Theology with a doctoral degree awarded on the basis of a short dissertation and an oral examination in Latin.[14]

Church career

Priest and Monsignor

While all other candidates from the Rome diocese were ordained in the Basilica of St. John Lateran,[15] Pacelli was ordained a priest on Easter Sunday, 2 April 1899 alone in the private chapel of a family friend the Vicegerent of Rome, Mgr Paolo Cassetta. Shortly after ordination he began postgraduate studies in canon law at Sant'Apollinaire. He received his first assignment as a curate at Chiesa Nuova.[16] In 1901 he entered the Congregation for Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs, a sub-office of the Vatican Secretariat of State.[17]

Monsignor Pietro Gasparri, the recently appointed undersecretary at the Department of Extraordinary Affairs, had underscored his proposal to Pacelli to work in the "Vatican's equivalent of the Foreign office" by highlighting the "necessity of defending the Church from the onslaughts of secularism and liberalism throughout Europe".[18] Pacelli became an apprendista, an apprentice, in Gasparri's department. In January 1901 he was also chosen, by Pope Leo XIII himself, according to an official account, to deliver condolences on behalf of the Vatican to King Edward VII of the UK after the death of Queen Victoria.[19]

By 1904 Pacelli received his doctorate. The theme of his thesis was the nature of concordats and the function of canon law when a concordat falls into abeyance. Promoted to the position of minutante, he prepared digests of reports that had been sent to the Secretariat from all over the world and in the same year became a papal chamberlain. In 1905 he received the title domestic prelate.[16] From 1904 until 1916, he assisted Cardinal Pietro Gasparri in his codification of canon law with the Department of Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs.[20] According to John Cornwell "the text, together with the Anti-Modernist Oath, became the means by which the Holy See was to establish and sustain the new, unequal, and unprecedented power relationship that had arisen between the papacy and the Church".[21]

In 1908, Pacelli served as a Vatican representative on the International Eucharistic Congress, accompanying Rafael Merry del Val[22] to London,[19] where he met Winston Churchill.[23] In 1911, he represented the Holy See at the coronation of King George V.[20] Pacelli became the under-secretary in 1911, adjunct-secretary in 1912 (a position he received under Pope Pius X and retained under Pope Benedict XV), and secretary of the Department of Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs in February 1914.[20] On 24 June 1914, just four days before Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria was assassinated in Sarajevo, Pacelli, together with Cardinal Merry del Val, represented the Vatican when the Serbian Concordat was signed. Serbia's success in the First Balkan War against Turkey in 1912 had increased the number of Catholics within greater Serbia. At this time Serbia, encouraged by Russia, was challenging Austria-Hungary's sphere of influence throughout the Balkans. Pius X died on 20 August 1914. His successor Benedict XV named Gasparri as secretary of state and Gasparri took Pacelli with him into the Secretariat of State, making him undersecretary.[24] During World War I, Pacelli maintained the Vatican's registry of prisoners of war and worked to implement papal relief initiatives. In 1915, he travelled to Vienna to assist Monsignor Raffaele Scapinelli, nuncio to Vienna, in his negotiations with Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria regarding Italy.[25]

Archbishop and Papal nuncio

Pope Benedict XV appointed Pacelli as nuncio to Bavaria on 23 April 1917, consecrating him as titular Archbishop of Sardis in the Sistine Chapel on 13 May 1917. After his consecration, Eugenio Pacelli left for Bavaria. As there was no nuncio to Prussia or Germany at the time, Pacelli was, for all practical purposes, the nuncio to all of the German Empire.

Once in Munich, he conveyed the papal initiative to end the war to German authorities.[26] He met with King Ludwig III on 29 May, and later with Kaiser Wilhelm II[27] and Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg, who replied positively to the Papal initiative. However, Bethmann-Hollweg was forced to resign and the German High Command, hoping for a military victory, delayed the German reply until 20 September.

Sister Pascalina later recalled that the Nuncio was heartbroken that the Kaiser turned a "deaf ear to all his proposals". She later wrote, "Thinking back today on that time, when we Germans still all believed that our weapons would be victorious and the Nuncio was deeply sorry that the chance had been missed to save what there was to save, it occurs to me over and over again how clearly he foresaw what was to come. Once as he traced the course of the Rhine with his finger on a map, he said sadly, 'No doubt this will be lost as well'. I did not want to believe it, but here, too, he was to be proved right."[28]

For the remainder of the Great War, Pacelli concentrated on Benedict's humanitarian efforts[29] especially among Allied POWs in German custody.[30] In the upheaval following the Armistice, a disconcerted Pacelli sought Benedict XV's permission to leave Munich, where Kurt Eisner had formed the Free State of Bavaria, and he left for a while to Rorschach, and a tranquil Swiss sanatorium run by nuns. Monsignor Schioppa, the uditore, was left in Munich.[31]

"His recovery began with a 'rapport'" with the 24-year-old Sister Pascalina Lehnert—she would soon be transferred to Munich when Pacelli "pulled strings at the highest level".[32]

When he returned to Munich, following Eisner's assassination by an anti-Semitic extreme nationalist, Count Anton von Arco auf Valley, he informed Gasparri-using Schioppa's eye-witness testimony of the chaotic scene at the former royal palace as the trio of Max Levien, Eugen Levine, and Towia Axelrod sought power: "the scene was indescribable [-] the confusion totally chaotic [-] in the midst of all this, a gang of young women, of dubious appearance, Jews like the rest of them hanging around [-] the boss of this female rabble was Levien's mistress, a young Russian woman, a Jew and a divorcée [-] and it was to her that the nunciature was obliged to pay homage in order to proceed [-] Levien is a young man, also Russian and a Jew. Pale, dirty, with drugged eyes, vulgar, repulsive ..." John Cornwell alleges that a worrying impression of anti-Semitism is discernible in the "catalogue of epithets describing their physical and moral repulsiveness" and Pacelli's "constant harping on the Jewishness of this party of power usurpers" chimed with the "growing and widespread belief among Germans that the Jews were the instigators of the Bolshevik revolution, their principal aim being the destruction of Christian civilization".[33] Also according to Cornwell, Pacelli informed Gasparri that "the capital of Bavaria, is suffering under a harsh Jewish-Russian revolutionary tyranny".[34]

According to Sister Pascalina Lehnert, the Nuncio was repeatedly threatened by emissaries of the Bavarian Soviet Republic. Once, in a violation of international law, the Bavarian Revolutionary Government attempted to confiscate the Nunciature's car at gunpoint. Despite their demands, however, Pacelli refused to leave his post.[35]

After the Munich Soviet Republic was defeated and toppled by Freikorps and Reichswehr troops, the Nuncio focused on, according to Lehnert, "alleviating the distress of the postwar period, consoling, supporting all in word and deed".[36]

Pacelli was appointed Apostolic Nuncio to Germany on 23 June 1920, and—after the completion of a Bavarian concordat—his nunciature was moved to Berlin in August 1925. Many of Pacelli's Munich staff stayed with him for the rest of his life, including his advisor Robert Leiber and Sister Pascalina Lehnert—housekeeper, cook, friend, and adviser for 41 years. In Berlin, Pacelli was Dean of the Diplomatic Corps and active in diplomatic and many social activities. He was aided by the German priest Ludwig Kaas, who was known for his expertise in Church-state relations and was a full-time politician, politically active in the Catholic Centre Party, a party he led following Wilhelm Marx's resignation in October 1928.[37] While in Germany, he travelled to all regions, attended Katholikentag (national gatherings of the faithful), and delivered some 50 sermons and speeches to the German people.[38] In Berlin he lived in the Tiergarten quarter and threw parties for the official and diplomatic elite. Paul von Hindenburg, Gustav Stresemann, and other members of the Cabinet were regular guests.

In post-war Germany, in the absence of a nuncio in Moscow, Pacelli worked also on diplomatic arrangements between the Vatican and the Soviet Union. He negotiated food shipments for Russia, where the Church was persecuted. He met with Soviet representatives including Foreign Minister Georgi Chicherin, who rejected any kind of religious education, the ordination of priests and bishops, but offered agreements without the points vital to the Vatican.[39]

Despite Vatican pessimism and a lack of visible progress, Pacelli continued the secret negotiations, until Pius XI ordered them to be discontinued in 1927. Pacelli supported German diplomatic activity aimed at rejection of punitive measures from victorious former enemies. He blocked French attempts for an ecclesiastical separation of the Saar region, supported the appointment of a papal administrator for Danzig and aided the reintegration of priests expelled from Poland.[40] A Prussian Concordat was signed on 14 June 1929. Following the Wall Street Crash of 1929, the beginnings of a world economic slump appeared, and the days of the Weimar Republic were numbered. Pacelli was summoned back to Rome at this time—the call coming by telegram when he was resting at his favourite retreat, the Rorschach convent sanatorium. He left Berlin on 10 December 1929.[41] David Dalin wrote "of the forty-four speeches Pacelli gave in Germany as papal nuncio between 1917 and 1929, forty denounced some aspect of the emerging Nazi ideology".[42] In 1935 he wrote a letter to the bishop of Cologne describing the Nazis as "false prophets with the pride of Lucifer". and as "bearers of a new faith and a new Evangile" who were attempting to create "a mendacious antimony between faithfulness to the Church and the Fatherland".[43] Two years later at Notre Dame in Paris he named Germany as "that noble and powerful nation whom bad shepherds would lead astray into an ideology of race".[42]

Cardinal Secretary of State and Camerlengo

Pacelli was made a Cardinal-Priest of Santi Giovanni e Paolo on 16 December 1929 by Pope Pius XI, and within a few months, on 7 February 1930, Pius XI appointed him Cardinal Secretary of State, responsible for foreign policy and state relations throughout the world. In 1935, Pacelli was named Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church.

As Cardinal Secretary of State, Pacelli signed concordats with a number of countries and states. Immediately on becoming Cardinal Secretary of State, Pacelli and Ludwig Kaas took up negotiations on a Baden Concordat which continued until the spring and summer of 1932. Papal fiat appointed a supporter of Pacelli and his concordat policy, Conrad Gröber, the new Archbishop of Freiburg, and the treaty was signed in August 1932.[44] Others followed: Austria (1933), Germany (1933), Yugoslavia (1935) and Portugal (1940). The Lateran treaties with Italy (1929) were concluded before Pacelli became Secretary of State. Catholicism had become the sole recognized religion; the powerful democratic Catholic Popular Party, in many ways similar to the Centre Party in Germany, had been disbanded, and in place of political Catholicism the Holy See encouraged Catholic Action, "an anaemic form of clerically dominated religious rally-rousing". It was permitted only so long as it developed "its activity outside every political party and in direct dependence upon the Church hierarchy for the dissemination and implementation of Catholic principles".[45] Such concordats allowed the Catholic Church to organize youth groups, make ecclesiastical appointments, run schools, hospitals, and charities, or even conduct religious services. They also ensured that canon law would be recognized within some spheres (e.g., church decrees of nullity in the area of marriage).[46]

As the decade began Pacelli wanted the Centre Party in Germany to turn away from the socialists. In the summer of 1931 he clashed with Catholic chancellor Heinrich Bruning, who frankly told Pacelli he believed that he "misunderstood the political situation in Germany and the real character of the Nazis".[47] Following Bruning's resignation in May 1932 Pacelli, like the new Catholic chancellor Franz von Papen, wondered if the Centre Party should look to the Right for a coalition, "that would correspond to their principles".[48] He made many diplomatic visits throughout Europe and the Americas, including an extensive visit to the United States in 1936 where he met President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who appointed a personal envoy—who did not require Senate confirmation—to the Holy See in December 1939, re-establishing a diplomatic tradition that had been broken since 1870 when the pope lost temporal power.[49]

Pacelli presided as Papal Legate over the International Eucharistic Congress in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 10–14 October 1934, and in Budapest in 25–30 May 1938.[50] At this time, anti-semitic laws were in the process of being formulated in Hungary. Pacelli made reference to the Jews "whose lips curse [Christ] and whose hearts reject him even today".[51] This traditional adversarial relationship with Judaism would be reversed in Nostra aetate issued during the Second Vatican Council.[52] According to Joseph Bottum, Pacelli in 1937 "warned A. W. Klieforth, the American consul to Berlin, that Hitler was 'an untrustworthy scoundrel and fundamentally wicked person', to quote Klieforth, who also wrote that Pacelli 'did not believe Hitler capable of moderation, and ... fully supported the German bishops in their anti-Nazi stand'. This was matched with the discovery of Pacelli's anti-Nazi report, written the following year for President Roosevelt and filed with Ambassador Joseph Kennedy, which declared that the Church regarded compromise with the Third Reich as 'out of the question'."[53]

Historian Walter Bussmann argued that Pacelli, as Cardinal Secretary of State, dissuaded Pope Pius XI—who was nearing death at the time[54]—from condemning the Kristallnacht in November 1938,[55] when he was informed of it by the papal nuncio in Berlin.[56]

The draft encyclical Humani generis unitas ("On the Unity of the Human Race") was ready in September 1938 but, according to those responsible for an edition of the document[57] and other sources, it was not forwarded to the Holy See by the Jesuit General Wlodimir Ledóchowski.[58][59] The draft encyclical contained an open and clear condemnation of colonialism, racial persecution and antisemitism.[58][60][61] Historians Passelecq and Suchecky have argued that Pacelli learned about the existence of the draft only after the death of Pius XI and did not promulgate it as Pope.[62] He did use parts of it in his inaugural encyclical Summi Pontificatus, which he titled "On the Unity of Human Society".[63] His various positions on Church and policy issues during his tenure as Cardinal Secretary of State were made public by the Holy See in 1939. Most noteworthy among the 50 speeches is his review of Church-State issues in Budapest in 1938.[64]

Reichskonkordat and Mit brennender Sorge

The Reichskonkordat was an integral part of four concordats Pacelli concluded on behalf of the Vatican with German States. The state concordats were necessary because the German federalist Weimar constitution gave the German states authority in the area of education and culture and thus diminished the authority of the churches in these areas; this diminution of church authority was a primary concern of the Vatican. As Bavarian Nuncio, Pacelli negotiated successfully with the Bavarian authorities in 1925. He expected the concordat with Catholic Bavaria to be the model for the rest of Germany.[65][66] Prussia showed interest in negotiations only after the Bavarian concordat. However, Pacelli obtained less favorable conditions for the Church in the Prussian concordat of 1929, which excluded educational issues. A concordat with the German state of Baden was completed by Pacelli in 1932, after he had moved to Rome. There he also negotiated a concordat with Austria in 1933.[67] A total of 16 concordats and treaties with European states had been concluded in the ten-year period 1922–1932.[68]

The Reichskonkordat, signed on 20 July 1933, between Germany and the Holy See, while thus a part of an overall Vatican policy, was controversial from its beginning. It remains the most important of Pacelli's concordats. It is debated, not because of its content, which is still valid today, but because of its timing. A national concordat with Germany was one of Pacelli's main objectives as secretary of state, because he had hoped to strengthen the legal position of the Church. Pacelli, who knew German conditions well, emphasized in particular protection for Catholic associations (§31), freedom for education and Catholic schools, and freedom for publications.[69]

As nuncio during the 1920s, he had made unsuccessful attempts to obtain German agreement for such a treaty, and between 1930 and 1933 he attempted to initiate negotiations with representatives of successive German governments, but the opposition of Protestant and Socialist parties, the instability of national governments and the care of the individual states to guard their autonomy thwarted this aim. In particular, the questions of denominational schools and pastoral work in the armed forces prevented any agreement on the national level, despite talks in the winter of 1932.[70][71]

Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor on 30 January 1933 and sought to gain international respectability and to remove internal opposition by representatives of the Church and the Catholic Centre Party. He sent his vice chancellor Franz von Papen, a Catholic nobleman, to Rome to offer negotiations about a Reichskonkordat.[72][73] On behalf of Pacelli, Prelate Ludwig Kaas, the outgoing chairman of the Centre Party, negotiated first drafts of the terms with Papen.[74] The concordat was finally signed, by Pacelli for the Vatican and von Papen for Germany, on 20 July and ratified on 10 September 1933.[75] Bishop Preysing cautioned against compromise with the new regime, against those who saw the Nazi persecution of the church as an aberration that Hitler would correct.[76]

Between 1933 and 1939, Pacelli issued 55 protests of violations of the Reichskonkordat. Most notably, early in 1937, Pacelli asked several German cardinals, including Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber to help him write a protest of Nazi violations of the Reichskonkordat; this was to become Pius XI's 1937 encyclical, Mit brennender Sorge. The encyclical was written in German and not the usual Latin of official Catholic Church documents. Secretly distributed by an army of motorcyclists and read from every German Catholic Church pulpit on Palm Sunday, it condemned the paganism of the National Socialism ideology.[77] Pius XI credited its creation and writing to Pacelli.[78] It was the first official denunciation of Nazism made by any major organization and resulted in persecution of the Church by the infuriated Nazis who closed all the participating presses and "took numerous vindictive measures against the Church, including staging a long series of immorality trials of the Catholic clergy".[79] On 10 June 1941, the pope commented on the problems of the Reichskonkordat in a letter to the Bishop of Passau, in Bavaria: "The history of the Reichskonkordat shows, that the other side lacked the most basic prerequisites to accept minimal freedoms and rights of the Church, without which the Church simply cannot live and operate, formal agreements notwithstanding".[80]

Relation with the Media

Cardinal Pacelli gave a lecture entitled "La Presse et L'Apostolat" at the Pontifical University of St. Thomas Aquinas, Angelicum on 17 April 1936.[81]

Papacy

Election and coronation

| Papal styles of Pope Pius XII | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Holiness |

| Spoken style | Your Holiness |

| Religious style | Holy Father |

| Posthumous style | Venerable |

Pope Pius XI died on 10 February 1939. Several historians have interpreted the conclave to choose his successor as facing a choice between a diplomatic or a spiritual candidate, and they view Pacelli's diplomatic experience, especially with Germany, as one of the deciding factors in his election on 2 March 1939, his 63rd birthday, after only one day of deliberation and three ballots.[83][84] He was the first cardinal Secretary of State to be elected pope since Clement IX in 1667.[85] He was one of only two men known to have served as Camerlengo immediately prior to being elected as pope (the other being Pope Leo XIII). According to rumours, he asked for another ballot to be taken to ensure the validity of his election. After his election was indeed confirmed, he chose the name Pius XII in honour of his immediate predecessor.

His coronation took place on 12 March 1939. Upon being elected pope he was also formally the Grand Master of the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem, prefect of the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office, prefect of the Sacred Congregation for the Oriental Churches and prefect of the Sacred Consistorial Congregation. There was however a Cardinal-Secretary to run these bodies on a day-to-day basis.

Pacelli took the same papal name as his predecessor, a title used exclusively by Italian Popes. He was quoted as saying "I call myself Pius; my whole life was under Popes with this name, but especially as a sign of gratitude towards Pius XI."[86] On 15 December 1937, during his last consistory, Pius XI strongly hinted to the cardinals that he expected Pacelli to be his successor, saying "He is in your midst."[87][88] He had previously been quoted as saying: "When today the Pope dies, you'll get another one tomorrow, because the Church continues. It would be a much bigger tragedy, if Cardinal Pacelli dies, because there is only one. I pray every day, God may send another one into one of our seminaries, but as of today, there is only one in this world."[89]

Appointments

After his election, he made Luigi Maglione his successor as Cardinal Secretary of State. Cardinal Maglione, a seasoned Vatican diplomat, had reestablished diplomatic relations with Switzerland and was for many years nuncio in Paris. Yet, Maglione did not exercise the influence of his predecessor Pacelli, who as Pope continued his close relation with Monsignors Montini (later Pope Paul VI) and Domenico Tardini. After the death of Maglione in 1944, Pius left the position open and named Tardini head of its foreign section and Montini head of the internal section.[90] Tardini and Montini continued serving there until 1953, when Pius XII decided to appoint them cardinals,[91] an honor which both turned down.[92] They were then later appointed to be Pro-Secretary with the privilege to wear Episcopal Insignia.[93] Tardini continued to be a close co-worker of the Pope until the death of Pius XII, while Montini became archbishop of Milan, after the death of Alfredo Ildefonso Schuster.

Pius XII slowly eroded the Italian monopoly on the Roman Curia; he employed German and Dutch Jesuit advisors, Robert Leiber, Augustin Bea, and Sebastian Tromp. He also supported the elevation of Americans such as Cardinal Francis Spellman from a minor to a major role in the Church.[94][95] After World War II, Pius XII appointed more non-Italians than any Pope before him. American appointees included Joseph P. Hurley as regent of the nunciature in Belgrade, Gerald P. O'Hara as nuncio to Romania, and Monsignor Muench as nuncio to Germany. For the first time, numerous young Europeans, Asians and "Americans were trained in various congregations and secretariats within the Vatican for eventual service throughout the world".[96]

Consistories

Only twice in his pontificate did Pius XII hold a consistory to create new cardinals, in contrast to Pius XI, who had done so 17 times in as many years. Pius XII chose not to name new cardinals during World War II, and the number of cardinals shrank to 38, with Dennis Joseph Dougherty of Philadelphia being the only living U.S. cardinal. The first occasion on 18 February 1946—which has become known as the "Grand Consistory"—yielded the elevation of a record 32 new cardinals, almost 50 percent of the College of Cardinals and reaching the canonical limit of 70 cardinals.[97] In the 1946 consistory, Pius XII, while maintaining the maximum size of the College of Cardinals at 70, named cardinals from China, India, the Middle East and increased the number of Cardinals from the Americas, proportionally lessening the Italian influence.[98]

In his second consistory on 12 January 1953, it was expected that his closest co-workers, Msgrs. Domenico Tardini and Giovanni Montini would be elevated[99] and Pius XII informed the assembled cardinals that both of them were originally on the top of his list,[100] but they had turned down the offer, and were rewarded instead with other promotions.[101] Both Montini and Tardini would become Cardinals shortly after Pius' death; Montini later became Pope Paul VI. The two consistories of 1946 and 1953 brought an end to over five hundred years of Italians constituting a majority of the College of Cardinals.[102]

With few exceptions, Italian prelates accepted the changes positively; there was no protest movement or open opposition to the internationalization efforts.[103]

Church reforms

Liturgy reforms

In his encyclical Mediator Dei, Pius XII links liturgy with the last will of Jesus Christ.

But it is His will, that the worship He instituted and practiced during His life on earth shall continue ever afterwards without intermission. For He has not left mankind an orphan. He still offers us the support of His powerful, unfailing intercession, acting as our "advocate with the Father". He aids us likewise through His Church, where He is present indefectibly as the ages run their course: through the Church which He constituted "the pillar of truth" and dispenser of grace, and which by His sacrifice on the cross, He founded, consecrated and confirmed forever.[104]

The Church has, therefore, according to Pius XII, a common aim with Christ himself, teaching all men the truth, and offering to God a pleasing and acceptable sacrifice. This way, the Church re-establishes the unity between the Creator and His creatures.[105] The Sacrifice of the Altar, being Christ's own actions, conveys and dispenses divine grace from Christ to the members of the Mystical Body.[106]

Bishop Carlos Duarte Costa, a long-time critic of Pius XII's policies during World War II and an opponent of clerical celibacy and the use of Latin as language of the liturgy, was excommunicated by Pius XII on 2 July 1945.[107]

The numerous reforms of Pius XII show two characteristics: renewal and rediscovery of old liturgical traditions, such as the reintroduction of the Easter Vigil, and a more structured atmosphere within the Church buildings.

Canon Law reforms

Decentralized authority and increased independence of the Uniate Churches were aimed at in the Canon Law/Codex Iuris Canonici (CIC) reform. In its new constitutions, Eastern Patriarchs were made almost independent from Rome (CIC Orientalis, 1957) Eastern marriage law (CIC Orientalis, 1949), civil law (CIC Orientalis, 1950), laws governing religious associations (CIC Orientalis, 1952) property law (CIC Orientalis, 1952) and other laws. These reforms and writings of Pius XII were intended to establish Eastern Orientals as equal parts of the mystical body of Christ, as explained in the encyclical Mystici corporis.

Priests and religious

With the Apostolic constitution Sedis Sapientiae, Pius XII added social sciences, sociology, psychology and social psychology, to the pastoral training of future priests. Pius XII emphasised the need to systematically analyze the psychological condition of candidates to the priesthood to ensure that they are capable of a life of celibacy and service.[108] Pius XII added one year to the theological formation of future priests. He included a "pastoral year", an introduction into the practice of parish work.[109]

Pius XII wrote in Menti Nostrae that the call to constant interior reform and Christian heroism means to be above average, to be a living example of Christian virtue. The strict norms governing their lives are meant to make them models of Christian perfection for lay people.[110] Bishops are encouraged to look at model saints like Boniface, and Pope Pius X.[111] Priests were encouraged to be living examples of the love of Christ and his sacrifice.[112]

Theology

Pius XII explained the Catholic faith in 41 encyclicals and almost 1000 messages and speeches during his long pontificate. Mediator Dei clarified membership and participation in the Church. The encyclical Divino afflante Spiritu opened the doors for biblical research. His magisterium was far larger and is difficult to summarize. In numerous speeches Catholic teaching is related to various aspects of life, education, medicine, politics, war and peace, the life of saints, Mary, the Mother of God, things eternal and contemporary. Theologically, Pius XII specified the nature of the teaching authority of the Church. He also gave a new freedom to engage in theological investigations.[113]

Biblical research

The encyclical Divino afflante Spiritu, published in 1943,[114] emphasized the role of the Bible. Pius XII freed biblical research from previous limitations. He encouraged Christian theologians to revisit original versions of the Bible in Greek and Hebrew. Noting improvements in archaeology, the encyclical reversed Pope Leo XIII's encyclical, which had only advocated going back to the original texts to resolve ambiguity in the Latin Vulgate. The encyclical demands a much better understanding of ancient Hebrew history and traditions. It requires bishops throughout the Church to initiate biblical studies for lay people. The Pontiff also requests a reorientation of Catholic teaching and education, relying much more on sacred scriptures in sermons and religious instruction.[115]

The role of theology

This theological investigative freedom does not, however, extend to all aspects of theology. According to Pius, theologians, employed by the Church, are assistants, to teach the official teachings of the Church and not their own private thoughts. They are free to engage in empirical research, which the Church generously supports, but in matters of morality and religion, they are subjected to the teaching office and authority of the Church, the Magisterium. "The most noble office of theology is to show how a doctrine defined by the Church is contained in the sources of revelation, ... in that sense in which it has been defined by the Church."[116] The deposit of faith is authentically interpreted not to each of the faithful, not even to theologians, but only to the teaching authority of the Church.[117]

Mariology and the dogma of the Assumption

World consecration to the Immaculate Heart of Mary

As a young boy and in later life, Pacelli was an ardent follower of the Virgin Mary. He was consecrated as a bishop on 13 May 1917, the very first day of the apparitions of Our Lady of Fátima. Based on the Portuguese mystic Blessed Alexandrina of Balazar requests, he consecrated the world to the Immaculate Heart of Mary in 1942. His remains were to be buried in the crypt of Saint Peter's Basilica on the feast day of Our Lady of Fátima, 13 October 1958.

The dogma of the Assumption of Mary

On 1 November 1950, Pius XII invoked papal infallibility for the first time since 1854 by defining the dogma of the Assumption of Mary, namely that she "having completed the course of her earthly life, was assumed body and soul into heavenly glory".[118] To date this is the last time full papal infallibility has been used. The dogma was preceded by the 1946 encyclical Deiparae Virginis Mariae, which requested all Catholic bishops to express their opinion on a possible dogmatization. On 8 September 1953, the encyclical Fulgens corona announced a Marian year for 1954, the centennial of the Dogma of the Immaculate Conception.[119] In the encyclical Ad caeli reginam he promulgated the Queenship of Mary feast.[120] Mystici corporis summarizes his mariology.[121] On 15 August 1954, the Feast of the Assumption, he initiated the practice of leading the Angelus every Sunday before address to the crowd assembled at Castel Gandolfo.[122]

Social teachings

Medical theology

Pius XII delivered numerous speeches to medical professionals and researchers.[123] He addressed doctors, nurses, midwives, to detail all aspects of rights and dignity of patients, medical responsibilities, moral implications of psychological illnesses and the uses of psycho pharmaca. He also took on issues like the uses of medicine in terminally ill persons, medical lies in face of grave illness, and the rights of family members to make decisions against expert medical advice. Pope Pius XII often reconsidered previously accepted truth, thus he was first to determine that the use of pain medicine in terminally ill patients is justified, even if this may shorten the life of the patient, as long as life shortening is not the objective itself.[124]

Family and sexuality

Pope Pius XII developed an extensive theology of the family, taking issue with family roles, sharing of household duties, education of children, conflict resolution, financial dilemmas, psychological problems, illness, taking care of older generations, unemployment, marital holiness and virtue, common prayer, religious discussions and more. He accepted the rhythm method as a moral form of family planning, although only in limited circumstances, within the context of family.[125]

Theology and science

To Pius XII, science and religion were heavenly sisters, different manifestations of divine exactness, who could not possibly contradict each other over the long term.[126] Regarding their relation, his advisor Professor Robert Leiber wrote: "Pius XII was very careful not to close any doors prematurely. He was energetic on this point and regretted that in the case of Galileo".[127]

Evolution of the human body

In 1950, Pius XII promulgated Humani generis, which acknowledged that evolution might accurately describe the biological origins of the human form, but at the same time criticized those who "imprudently and indiscreetly hold that evolution ... explains the origin of all things". Catholics must believe that the human soul was created immediately by God. Since the soul is a spiritual substance, it is not brought into being through transformation of matter, but directly by God, whence the special uniqueness of each person.[128] Fifty years later, Pope John Paul II, stating that scientific evidence now seemed to favour the evolutionary theory, upheld the distinction of Pius XII regarding the human soul. "Even if the human body originates from pre-existent living matter, the spiritual soul is spontaneously created by God."[129]

Capital punishment

In an address given on 14 September 1952, Pope Pius XII said that the Church does not regard the execution of criminals as a violation by the State of the universal right to life:

When it is a question of the execution of a condemned man, the State does not dispose of the individual's right to life. In this case it is reserved to the public power to deprive the condemned person of the enjoyment of life in expiation of his crime when, by his crime, he has already disposed himself of his right to live.[130]

The Church regards criminal penalties as both "medicinal", preventing the criminal from re-offending, and "vindictive", providing retribution for the offense committed. Pius defended the authority of the State to carry out punishment, up to and including the death penalty.[131]

True democracy

Pius XII taught that the masses were a threat to true democracy. In such a democracy, liberty is the individual's moral duty and equality is the right of all people to honorably live in the place and station that God has assigned them.[132]

Encyclicals, writings and speeches

Pius XII issued 41 encyclicals during his pontificate—more than all his successors in the past 50 years taken together—along with many other writings and speeches. The pontificate of Pius XII was the first in Vatican history that published papal speeches and addresses in vernacular language on a systematic basis. Until then, papal documents were issued mainly in Latin in Acta Apostolicae Sedis since 1909. Because of the novelty of it all, and a feared occupation of the Vatican by the German Wehrmacht, not all documents exist today. In 1944, a number of papal documents were burned or "walled in",[135] to avoid detection by the advancing German army. Insisting that all publications must be reviewed by him on a prior basis to avoid any misunderstanding, several speeches by Pius XII, who did not find sufficient time, were never published or appeared only once issued in the Vatican daily, Osservatore Romano.

Several encyclicals addressed the Eastern Catholic Churches. Orientalis Ecclesiae was issued in 1944 on the 15th centenary of the death of Cyril of Alexandria, a saint common to Eastern Christianity and Latin Churches. Pius XII asks for prayer for better understanding and unification of the Churches. Orientales omnes Ecclesias, issued in 1945 on the 350th anniversary of the reunion, is a call to continued unity of the Ruthenian Greek Catholic Church, threatened in its very existence by the authorities of the Soviet Union. Sempiternus Rex was issued in 1951 on the 1500th anniversary of the Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon. It included a call to oriental communities adhering to Miaphysite theology to return to the Catholic Church. Orientales Ecclesias was issued in 1952 and addressed to the Eastern Churches, protesting the continued Stalinist persecution of the Church. Several Apostolic Letters were sent to the bishops in the East. On 13 May 1956, Pope Pius addressed all bishops of the Eastern Rite. Mary, the mother of God, was the subject of encyclical letters to the people of Russia in Fulgens corona, as well as a papal letter to the people of Russia.[136][137][138][139][140][141][142]

Pius XII made two substantial interventions on the media. His 1955 discourse The Ideal Movie, originally given in two parts to members of the Italian cinema industry, offered a "sophisticated analysis of the film industry and the role of cinema in modern society".[143] Compared to his predecessor's teaching, the encyclical Miranda Prorsus (1957) shows a "high regard for the importance of cinema, television, and radio".[144]

Feasts and devotions

In 1958, Pope Pius XII declared the Feast of the Holy Face of Jesus as Shrove Tuesday (the Tuesday before Ash Wednesday) for all Catholics. The first medal of the Holy Face, produced by Sister Maria Pierina De Micheli, based on the image on the Shroud of Turin had been offered to Pius XII who approved the medal and the devotion based on it. The general devotion to the Holy Face of Jesus had been approved by Pope Leo XIII in 1885 before the image on the Turin Shroud had been photographed.[145][146]

Canonisations and beatifications

Pope Pius XII canonized numerous people, including Pope Pius X—"both were determined to stamp out, as far as possible, all traces of dangerous heterodoxy"[147]—and Maria Goretti. He beatified Pope Innocent XI. The first canonizations were two women, the founder of a female order, Mary Euphrasia Pelletier, and a young laywoman, Gemma Galgani. Pelletier had a reputation for opening new ways for Catholic charities, helping people in difficulties with the law, who had been neglected by the system and the Church. Galgani was a virtuous woman in her twenties, said to have the stigmata.[148]

World War II

During World War II Pius saw his primary obligation as being to ensure the continuation of the "Church visible" and its divine mission.[149] Pius XII lobbied world leaders to prevent the outbreak of World War II and then expressed his dismay that war had come in his October 1939 Summi Pontificatus encyclical. He followed a strict public policy of Vatican neutrality for the duration of the conflict mirroring that of Pope Benedict XV.

In 1939, Pius XII turned the Vatican into a centre of aid which he organized from various parts of the world.[150] At the request of the Pope, an information office for prisoners of war and refugees operated in the Vatican under Giovanni Battista Montini, which in the years of its existence from 1939 until 1947 received almost 10 million (9,891,497) information requests and produced over 11 million (11,293,511) answers about missing persons.[151]

McGoldrick (2012) concludes that during the war:

Pius XII had genuine affection for Germany, though not the criminal element into whose hands it had fallen; he feared Bolshevism, an ideology dedicated to the annihilation of the church of which he was head, but his sympathies lay with the Allies and the democracies, especially the United States, into whose war economy he had transferred and invested the Vatican's considerable assets.[152]

Summi Pontificatus

Summi Pontificatus was the first papal encyclical issued by Pope Pius XII, in October 1939 and established some of the themes of his pontificate. During the drafting of the letter, the Second World War commenced with the German/Soviet invasion of Catholic Poland—the "dread tempest of war is already raging despite all Our efforts to avert it". The papal letter denounced antisemitism, war, totalitarianism, the attack on Poland and the Nazi persecution of the Church.[153]

Pius XII reiterated Church teaching on the "principle of equality"—with specific reference to Jews: "there is neither Gentile nor Jew, circumcision nor uncircumcision".[154] The forgetting of solidarity "imposed by our common origin and by the equality of rational nature in all men" was called "pernicious error".[155] Catholics everywhere were called upon to offer "compassion and help" to the victims of the war.[156] The Pope declared determination to work to hasten the return of peace and trust in prayers for justice, love and mercy, to prevail against the scourge of war.[157] The letter also decried the deaths of noncombatants.[158]

Following themes addressed in Non abbiamo bisogno (1931); Mit brennender Sorge (1937) and Divini redemptoris (1937), Pius wrote against "anti-Christian movements" and needing to bring back to the Church those who were following "a false standard ... misled by error, passion, temptation and prejudice, [who] have strayed away from faith in the true God".[159] Pius wrote of "Christians unfortunately more in name than in fact" having shown "cowardice" in the face of persecution by these creeds, and endorsed resistance:[159]

Who among "the Soldiers of Christ" – ecclesiastic or layman – does not feel himself incited and spurred on to a greater vigilance, to a more determined resistance, by the sight of the ever-increasing host of Christ's enemies; as he perceives the spokesmen of these tendencies deny or in practice neglect the vivifying truths and the values inherent in belief in God and in Christ; as he perceives them wantonly break the Tables of God's Commandments to substitute other tables and other standards stripped of the ethical content of the Revelation on Sinai, standards in which the spirit of the Sermon on the Mount and of the Cross has no place?

Pius wrote of a persecuted Church[160] and a time requiring "charity" for victims who had a "right" to compassion. Against the invasion of Poland and killing of civilians he wrote:[153]

[This is an] "Hour of Darkness"... in which the spirit of violence and of discord brings indescribable suffering on mankind... The nations swept into the tragic whirlpool of war are perhaps as yet only at the "beginnings of sorrows"... but even now there reigns in thousands of families death and desolation, lamentation and misery. The blood of countless human beings, even noncombatants, raises a piteous dirge over a nation such as Our dear Poland, which, for its fidelity to the Church, for its services in the defense of Christian civilization, written in indelible characters in the annals of history, has a right to the generous and brotherly sympathy of the whole world, while it awaits, relying on the powerful intercession of Mary, Help of Christians, the hour of a resurrection in harmony with the principles of justice and true peace.

With Italy not yet an ally of Hitler in the war, Italians were called upon to remain faithful to the Church. Pius avoided explicit denunciations of Hitlerism or Stalinism, establishing the "impartial" public tone which would become controversial in later assessment of his pontificate: "A full statement of the doctrinal stand to be taken in face of the errors of today, if necessary, can be put off to another time unless there is disturbance by calamitous external events; for the moment We limit Ourselves to some fundamental observations."[161]

Invasion of Poland

In Summi Pontificatus, Pius expressed dismay at the killing of non-combatants in the Nazi/Soviet invasion of Poland and expressed hope for the "resurrection" of that country. The Nazis and Soviets commenced a persecution of the Catholic Church in Poland. In April 1940, the Vatican advised the US government that its efforts to provide humanitarian aid had been blocked by the Germans and that the Holy See had been forced to seek indirect channels through which to direct its aid.[162] Michael Phayer, a critic of Pius XII, assesses his policy as having been to "refuse to censure" the "German" invasion and annexation of Poland. This, Phayer wrote, was regarded as a "betrayal" by many Polish Catholics and clergy, who saw his appointment of Hilarius Breitinger as the apostolic administrator for the Wartheland in May 1942, an "implicit recognition" of the breakup of Poland; the opinions of the Volksdeutsche, mostly German Catholic minorities living in occupied Poland, were more mixed.[163] Phayer argues that Pius XII—both before and during his papacy—consistently "deferred to Germany at the expense of Poland", and saw Germany—not Poland—as critical to "rebuilding a large Catholic presence in Central Europe".[164] In May 1942, Kazimierz Papée, Polish ambassador to the Vatican, complained that Pius had failed to condemn the recent wave of atrocities in Poland; when Cardinal Secretary of State Maglione replied that the Vatican could not document individual atrocities, Papée declared, "when something becomes notorious, proof is not required".[165] Although Pius XII received frequent reports about atrocities committed by and/or against Catholics, his knowledge was incomplete; for example, he wept after the war on learning that Cardinal Hlond had banned German liturgical services in Poland.[166]

There was a well-known case of Jewish Rabbis who, seeking support against the Nazi persecution of Polish Jews in the General Government (Nazi-occupied Polish zone), complained to the representatives of the Catholic Church. The Church's attempted intervention caused the Nazis to retaliate by arresting rabbis and deporting them to the death camp. Subsequently, the Catholic Church in Poland abandoned direct intervention, instead focusing on organizing underground aid, with huge international support orchestrated by Pope Pius XII and his Holy See. The Pope was informed about Nazi atrocities committed in Poland by both officials of the Polish Church and the Polish Underground. Those intelligence materials were used by Pius XII on 11 March 1940 during a formal audience with Joachim von Ribbentrop (Hitler's foreign affairs adviser) when Pope was "listing the date, place, and precise details of each crime" as described by Joseph L. Lichten [167] after others.

Early actions to end conflict

With Poland overrun, but France and the Low Countries yet to be attacked, Pius continued to hope for a negotiated peace to prevent the spread of the conflict. The similarly-minded US President Franklin D. Roosevelt re-established American diplomatic relations with the Vatican after a seventy-year hiatus and dispatched Myron C. Taylor as his personal representative.[168] Pius warmly welcomed Roosevelt's envoy and peace initiative, calling it "an exemplary act of fraternal and hearty solidarity... in defence against the chilling breath of aggressive and deadly godless anti-Christian tendencies".[169] American correspondence spoke of "parallel endeavours for peace and the alleviation of suffering".[170] Despite the early collapse of peace hopes, the Taylor mission continued at the Vatican.[168]

According to Hitler biographer John Toland, following the November 1939 assassination attempt by Johann Georg Elser, Hitler said Pius would have wanted the plot to succeed: "he's no friend of mine".[171] In the spring of 1940, a group of German generals seeking to overthrow Hitler and make peace with the British approached Pope Pius XII, who acted as an interlocutor between the British and the abortive plot.[172] According to Toland, Munich lawyer, Joseph Muller, made a clandestine trip to Rome in October 1939, met with Pius XII and found him willing to act as intermediary. The Vatican agreed to send a letter outlining the bases for peace with England and the participation of the Pope was used to try to persuade senior German Generals Franz Halder and Walther von Brauchitsch to act against Hitler.[173]

Pius warned the Allies of the planned German invasion of the Low Countries in 1940.[174] In Rome in 1942, US envoy Myron C. Taylor, thanked the Holy See for the "forthright and heroic expressions of indignation made by Pope Pius XII when Germany invaded the Low countries".[175] After Germany invaded the Low Countries during 1940, Pius XII sent expressions of sympathy to the Queen of the Netherlands, the King of Belgium, and the Grand Duchess of Luxembourg. When Mussolini learned of the warnings and the telegrams of sympathy, he took them as a personal affront and had his ambassador to the Vatican file an official protest, charging that Pius XII had taken sides against Italy's ally Germany. Mussolini's foreign minister claimed that Pius XII was "ready to let himself be deported to a concentration camp, rather than do anything against his conscience".[176]

When in 1940, the Nazi Foreign Minister von Ribbentrop led the only senior Nazi delegation permitted an audience with Pius XII and asked why the Pope had sided with the Allies, Pius replied with a list of recent Nazi atrocities and religious persecutions committed against Christians and Jews, in Germany, and in Poland, leading the New York Times to headline its report "Jews Rights Defended" and write of "burning words he spoke to Herr Ribbentrop about religious persecution".[177] During the meeting, Ribbentrop suggested an overall settlement between the Vatican and the Reich government in exchange for Pius XII instructing the German bishops to refrain from political criticism of the German government, but no agreement was reached.[178]

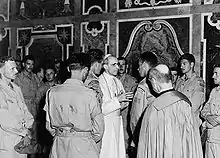

At a special mass at St Peters for the victims of the war, held in November 1940, soon after the commencement of the London Blitz bombing by the Luftwaffe, Pius preached in his homily: "may the whirlwinds, that in the light of day or the dark of night, scatter terror, fire, destruction, and slaughter on helpless folk cease. May justice and charity on one side and on the other be in perfect balance, so that all injustice be repaired, the reign of right restored".[179] Later he appealed to the Allies to spare Rome from aerial bombing, and visited wounded victims of the Allied bombing of 19 July 1943.[180]

Widening conflict

Pius attempted, unsuccessfully, to dissuade the Italian Dictator Benito Mussolini from joining Hitler in the war.[181] In April 1941, Pius XII granted a private audience to Ante Pavelić, the leader of the newly proclaimed Croatian state (rather than the diplomatic audience Pavelić had wanted).[182] Pius was criticised for his reception of Pavelić: an unattributed British Foreign Office memo on the subject described Pius as "the greatest moral coward of our age".[183] The Vatican did not officially recognise Pavelić's regime. Pius XII did not publicly condemn the expulsions and forced conversions to Catholicism perpetrated on Serbs by Pavelić;[184] however, the Holy See did expressly repudiate the forced conversions in a memorandum dated 25 January 1942, from the Vatican Secretariat of State to the Yugoslavian Legation.[185] The pope was well-informed of Catholic clergy involvement with the Ustaše regime, even possessing a list of clergymembers who had "joined in the slaughter", but decided against condemning the regime or taking action against the clergy involved, fearing that it would lead to schism in the Croatian church or undermine the formation of a future Croatian state.[186] Pius XII would elevate Aloysius Stepinac—a Croatian archbishop convicted of collaborating with the Ustaše by the newly established Yugoslav Communist regime—to the cardinalate in 1953.[187] Phayer agrees that Stepinac's was a "show trial", but states "the charge that he [Pius XII] supported the Ustaša regime was, of course, true, as everyone knew",[188] and that "if Stepinac had responded to the charges against him, his defense would have inevitably unraveled, exposing the Vatican's support of the genocidal Pavelić".[189] Throughout 1942, the Yugoslav government in exile sent letters of protest to Pius XII asking him to use all possible means to stop the massacres against the Serbs in the NDH, however Pius XII did nothing.[190]

In 1941, Pius XII interpreted Divini Redemptoris, an encyclical of Pope Pius XI, which forbade Catholics to help communists, as not applying to military assistance to the Soviet Union. This interpretation assuaged American Catholics who had previously opposed Lend-Lease arrangements with the Soviet Union.[191]

In March 1942, Pius XII established diplomatic relations with the Japanese Empire and received ambassador Ken Harada, who remained in that position until the end of the war.[192][193]

In June 1942, diplomatic relations were established with the Nationalist government of China. This step was envisaged earlier, but delayed due to Japanese pressure to establish relations with the pro-Japanese Wang Jingwei government. The first Chinese Minister to the Vatican, Hsieh Shou-kang, was only able to arrive at the Vatican in January 1943, due to difficulties of travel resulting from the war. He remained in that position until late 1946.[194]

The Pope employed the new technology of radio and a series of Christmas messages to preach against selfish nationalism and the evils of modern warfare and offer sympathy to the victims of the war.[180] Pius XII's 1942 Christmas address via Vatican Radio voiced concern at human rights abuses and the murder of innocents based on race. The majority of the speech spoke generally about human rights and civil society; at the very end of the speech, Pius XII mentioned "the hundreds of thousands of persons who, without any fault on their part, sometimes only because of their nationality or race, have been consigned to death or to a slow decline".[195] According to Rittner, the speech remains a "lightning rod" in debates about Pius XII.[196] The Nazis themselves responded to the speech by stating that it was "one long attack on everything we stand for. ... He is clearly speaking on behalf of the Jews. ... He is virtually accusing the German people of injustice toward the Jews, and makes himself the mouthpiece of the Jewish war criminals." The New York Times wrote that "The voice of Pius XII is a lonely voice in the silence and darkness enveloping Europe this Christmas. ... In calling for a 'real new order' based on 'liberty, justice and love', ... the pope put himself squarely against Hitlerism."[197] Historian Michael Phayer claims, however, that "it is still not clear whose genocide or which genocide he was referring to".[198] Speaking on the 50th anniversary of Pius's death in 2008, the German Pope Benedict XVI recalled that the Pope's voice had been "broken by emotion" as he "deplored the situation" with a "clear reference to the deportation and extermination of the Jews".[199]

Several authors have alleged a plot to kidnap Pius XII by the Nazis during their occupation of Rome in 1943 (Vatican City itself was not occupied); British historian Owen Chadwick and the Jesuit ADSS editor Rev. Robert Graham each concluded such claims were an intentional creation of the Political Warfare Executive.[200][201] However, in 2007, subsequent to those accounts, Dan Kurzman published a work which he maintains establishes that the plot was a fact.[202]

In 1944, Pius XII issued a Christmas message in which he warned against rule by the masses and against secular conceptions of liberty and equality.[132]

Final stages

As the war was approaching its end in 1945, Pius advocated a lenient policy by the Allied leaders in an effort to prevent what he perceived to be the mistakes made at the end of World War I.[203] On 23 August 1944, he met British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who was visiting Rome. At their meeting, the Pope acknowledged the justice of punishing war criminals, but expressed a hope that the people of Italy would not be punished, preferring that they be made "full allies" in the remaining war effort.[204]

Holocaust

.jpg.webp)

During the Second World War, after Nazi Germany commenced its mass executions of Jews in occupied Soviet territory, Pius XII employed diplomacy to aid victims of the Holocaust and directed the Church to provide discreet aid to Jews.[205] Upon his death in 1958, among many Jewish tributes, the Chief Rabbi of Rome Elio Toaff, said: "Jews will always remember what the Catholic Church did for them by order of the Pope during the Second World War. When the war was raging, Pius spoke out very often to condemn the false race theory."[206] This is disputed by commentator John Cornwell, who in his book, Hitler's Pope, argues that the pope was weak and vacillating in his approach to Nazism. Cornwell asserts that the pope did little to challenge the progressing holocaust of the Jews out of fear of provoking the Nazis into invading Vatican City.[207]

In his 1939 Summi Pontificatus first papal encyclical, Pius reiterated Catholic teaching against racial persecution and antisemitism and affirmed the ethical principles of the "Revelation on Sinai". At Christmas 1942, once evidence of mass executions of Jews had emerged, Pius XII voiced concern at the murder of "hundreds of thousands" of "faultless" people because of their "nationality or race" and intervened to attempt to block Nazi deportations of Jews in various countries. Upon his death in 1958, Pius was praised emphatically by the Israeli Foreign Minister, and other world leaders. But his insistence on Vatican neutrality and avoidance of naming the Nazis as the evildoers of the conflict became the foundation for contemporary and later criticisms from some quarters. His strongest public condemnation of genocide was considered inadequate by the Allied Powers, while the Nazis viewed him as an Allied sympathizer who had dishonored his policy of Vatican neutrality.[208] Hitler biographer John Toland, while scathing of Pius's cautious public comments in relation to the mistreatment of Jews, concluded that the Allies' own record of action against the Holocaust was "shameful", while "The Church, under the Pope's guidance, had already saved the lives of more Jews than all other churches, religious institutions and rescue organizations combined".[173]

In 1939, the newly elected Pope Pius XII appointed several prominent Jewish scholars to posts at the Vatican after they had been dismissed from Italian universities under Fascist leader Benito Mussolini's racial laws.[209] In 1939, the Pope employed a Jewish cartographer, Roberto Almagia, to work on old maps in the Vatican library. Almagia had been at the University of Rome since 1915 but was dismissed after Benito Mussolini's antisemitic legislation of 1938. The Pope's appointment of two Jews to the Vatican Academy of Science as well as the hiring of Almagia were reported by The New York Times in the editions of 11 November 1939 and 10 January 1940.[210]

Pius later engineered an agreement—formally approved on 23 June 1939—with Brazilian President Getúlio Vargas to issue 3,000 visas to "non-Aryan Catholics". However, over the next 18 months Brazil's Conselho de Imigração e Colonização (CIC) continued to tighten the restrictions on their issuance, including requiring a baptismal certificate dated before 1933, a substantial monetary transfer to the Banco do Brasil, and approval by the Brazilian Propaganda Office in Berlin. The program was cancelled 14 months later, after fewer than 1,000 visas had been issued, amid suspicions of "improper conduct" (i.e., continuing to practice Judaism) among those who had received visas.[56][211]

In April 1939, after the submission of Charles Maurras and the intervention of the Carmel of Lisieux, Pius XII ended his predecessor's ban on Action Française, a virulently antisemitic organization.[212][213]

Following the German/Soviet invasion of Poland, the Pope's first encyclical, Summi Pontificatus reiterated Catholic teaching against racial persecution and rejected antisemitism, quoting scripture singling out the "principle of equality"—with specific reference to Jews: "there is neither Gentile nor Jew, circumcision nor uncircumcision" and direct affirmation of the Jewish Revelation on Sinai.[214][215] The forgetting of solidarity "imposed by our common origin and by the equality of rational nature in all men" was called "pernicious error".[155] Catholics everywhere were called upon to offer "compassion and help" to the victims of the war.[156] The Pope declared determination to work to hasten the return of peace and trust in prayers for justice, love and mercy, to prevail against the scourge of war.[216] The letter also decried the deaths of noncombatants.[158]

Cardinal Secretary of State Luigi Maglione received a request from Chief Rabbi of Palestine Isaac Herzog in the spring of 1940 to intercede on behalf of Lithuanian Jews about to be deported to Germany.[56] Pius called Ribbentrop on 11 March, repeatedly protesting against the treatment of Jews.[213] In 1940, Pius asked members of the clergy, on Vatican letterhead, to do whatever they could on behalf of interned Jews.[217]

In 1941, Cardinal Theodor Innitzer of Vienna informed Pius of Jewish deportations in Vienna.[218] Later that year, when asked by French Marshal Philippe Pétain if the Vatican objected to antisemitic laws, Pius responded that the church condemned antisemitism, but would not comment on specific rules.[218] Similarly, when Philippe Pétain's regime adopted the "Jewish statutes", the Vichy ambassador to the Vatican, Léon Bérard (a French politician), was told that the legislation did not conflict with Catholic teachings.[219] Valerio Valeri, the nuncio to France, was "embarrassed" when he learned of this publicly from Pétain[220] and personally checked the information with Cardinal Secretary of State Maglione[221] who confirmed the Vatican's position.[222] In June 1942, Pius XII personally protested against the mass deportations of Jews from France, ordering the papal nuncio to protest to Pétain against "the inhuman arrests and deportations of Jews".[223] In September 1941, Pius XII objected to a Slovak Jewish Code,[224] which, unlike the earlier Vichy codes, prohibited intermarriage between Jews and non-Jews.[220] In October 1941, Harold Tittmann, a US delegate to the Vatican, asked the pope to condemn the atrocities against Jews; Pius replied that the Vatican wished to remain "neutral",[225] reiterating the neutrality policy which Pius invoked as early as September 1940.[219]

In 1942, the Slovak chargé d'affaires told Pius that Slovak Jews were being sent to concentration camps.[218] On 11 March 1942, several days before the first transport was due to leave, the chargé d'affaires in Bratislava reported to the Vatican: "I have been assured that this atrocious plan is the handwork of ... Prime Minister (Tuka), who confirmed the plan ... he dared to tell me—he who makes such a show of his Catholicism—that he saw nothing inhuman or un-Christian in it ... the deportation of 80,000 persons to Poland, is equivalent to condemning a great number of them to certain death." The Vatican protested to the Slovak government that it "deplore(s) these... measures which gravely hurt the natural human rights of persons, merely because of their race."[226]

On 18 September 1942, Pius XII received a letter from Monsignor Montini (future Pope Paul VI), saying "the massacres of the Jews reach frightening proportions and forms".[218] Later that month, Myron Taylor, U.S. representative to the Vatican, warned Pius that the Vatican's "moral prestige" was being injured by silence on European atrocities, a warning which was echoed simultaneously by representatives from the United Kingdom, Brazil, Uruguay, Belgium, and Poland.[227] Myron C. Taylor passed a US Government memorandum to Pius on 26 September 1942, outlining intelligence received from the Jewish Agency for Palestine which said that Jews from across the Nazi Empire were being systematically "butchered". Taylor asked if the Vatican might have any information which might "tend to confirm the reports", and if so, what the Pope might be able to do to influence public opinion against the "barbarities".[228] Cardinal Maglione handed Harold Tittmann a response to the letter on 10 October. The note thanked Washington for passing on the intelligence, and confirmed that reports of severe measures against the Jews had reached the Vatican from other sources, though it had not been possible to "verify their accuracy". Nevertheless, "every opportunity is being taken by the Holy See, however, to mitigate the suffering of these unfortunate people".[229] In December 1942, when Tittmann asked Cardinal Secretary of State Maglione if Pius would issue a proclamation similar to the Allied declaration "German Policy of Extermination of the Jewish Race", Maglione replied that the Vatican was "unable to denounce publicly particular atrocities".[230] Pius XII directly explained to Tittman that he could not name the Nazis without at the same time mentioning the Bolsheviks.[231]

Following the Nazi/Soviet invasion of Poland, Pius XII's Summi Pontificatus called for the sympathy of the whole world towards Poland, where "the blood of countless human beings, even noncombatants" was being spilled.[158] Pius never publicly condemned the Nazi massacre of 1,800,000–1,900,000 Poles, overwhelmingly Catholic (including 2,935 members of the Catholic clergy).[232][233] In late 1942, Pius XII advised German and Hungarian bishops to speak out against the massacres on the Eastern Front.[234] In his 1942 Christmas Eve message, he expressed concern for "those hundreds of thousands, who ... sometimes only by reason of their nationality or race, are marked down for death or progressive extinction.[235] On 7 April 1943, Msgr. Tardini, one of Pius XII's closest advisors, advised Pius XII that it would be politically advantageous after the war to take steps to help Slovak Jews.[236]

In January 1943, Pius XII declined to denounce publicly the Nazi discrimination against the Jews, following requests to do so from Władysław Raczkiewicz, president of the Polish government-in-exile, and Bishop Konrad von Preysing of Berlin.[237] According to Toland, in June 1943, Pius XII addressed the issue of mistreatment of Jews at a conference of the Sacred College of Cardinals and said: "Every word We address to the competent authority on this subject, and all Our public utterances have to be carefully weighed and measured by Us in the interests of the victims themselves, lest, contrary to Our intentions, We make their situation worse and harder to bear".[173]

On 26 September 1943, following the German occupation of northern Italy, Nazi officials gave Jewish leaders in Rome 36 hours to produce 50 kilograms (110 lb) of gold (or the equivalent) threatening to take 300 hostages. Then Chief Rabbi of Rome Israel Zolli recounts in his memoir that he was selected to go to the Vatican and seek help.[238] The Vatican offered to loan 15 kilos, but the offer proved unnecessary when the Jews received an extension.[239] Soon afterward, when deportations from Italy were imminent, 477 Jews were hidden in the Vatican itself and another 4,238 were protected in Roman monasteries and convents.[240] Eighty percent of Roman Jews were saved from deportation.[241] Phayer argues that the German diplomats in Rome were the "initiators of the effort to save the city's Jews", but holds that Pius XII "cooperated in this attempt at rescue", while agreeing with Zuccotti that the pope "did not give orders" for any Catholic institution to hide Jews.[242]

On 30 April 1943, Pius XII wrote to Bishop Graf von Preysing of Berlin to say: "We give to the pastors who are working on the local level the duty of determining if and to what degree the danger of reprisals and of various forms of oppression occasioned by episcopal declarations ... ad maiora mala vitanda (to avoid worse) ... seem to advise caution. Here lies one of the reasons, why We impose self-restraint on Ourselves in our speeches; the experience, that we made in 1942 with papal addresses, which We authorized to be forwarded to the Believers, justifies our opinion, as far as We see. ... The Holy See has done whatever was in its power, with charitable, financial and moral assistance. To say nothing of the substantial sums which we spent in American money for the fares of immigrants."[243]

On 28 October 1943, Ernst von Weizsäcker, the German Ambassador to the Vatican, telegraphed Berlin that "the Pope has not yet let himself be persuaded to make an official condemnation of the deportation of the Roman Jews. ... Since it is currently thought that the Germans will take no further steps against the Jews in Rome, the question of our relations with the Vatican may be considered closed."[244][245]

In March 1944, through the papal nuncio in Budapest, Angelo Rotta, the pope urged the Hungarian government to moderate its treatment of the Jews.[246] The pope ordered Rotta and other papal legates to hide and shelter Jews.[247] These protests, along with others from the King of Sweden, the International Red Cross, the United States, and Britain led to the cessation of deportations on 8 July 1944.[248] Also in 1944, Pius appealed to 13 Latin American governments to accept "emergency passports", although it also took the intervention of the U.S. State Department for those countries to honor the documents.[249] The Kaltenbrunner Report to Hitler, dated 29 November 1944, against the backdrop of the 20 July 1944 Plot to assassinate Hitler, states that the Pope was somehow a conspirator, specifically naming Eugenio Pacelli (Pope Pius XII), as being a party in the attempt.[250]

Jewish orphans controversy