Catuvellauni

The Catuvellauni (Gaulish: "war-chiefs") were a Celtic tribe or state of southeastern Britain before the Roman conquest, attested by inscriptions into the 4th century.

| Catuvellauni | |

|---|---|

| |

| Geography | |

| Capital | Verulamium (St. Albans) |

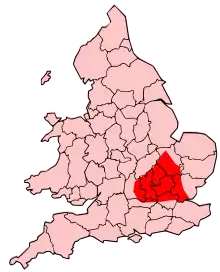

| Location | Modern Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire and Hertfordshire. (Also parts of Berkshire, Cambridgeshire, Essex, Greater London and Oxfordshire.) |

| Rulers | Tasciovanus Cunobeline Caratacus Togodumnus Epaticcus |

Obv: stylized crescents and wreaths with hidden faces.

Rev: Celtic warrior on horse right, carrying carnyx.

The fortunes of the Catuvellauni and their kings before the conquest can be traced through ancient coins and scattered references in classical histories. They are mentioned by Cassius Dio, who implies that they led the resistance against the conquest in AD 43. They appear as one of the civitates of Roman Britain in Ptolemy's Geography in the 2nd century, occupying the town of Verlamion (modern St Albans) and the surrounding areas of Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire and southern Cambridgeshire.

Their territory was bordered to the north by the Iceni and Corieltauvi, to the east by the Trinovantes, to the west by the Dobunni and Atrebates, and to the south by the Regnenses and Cantiaci.

Name

The name 'Catuvellauni' (Gaulish: Catu-uellauni 'war-chiefs, chiefs-of-war') stems from the Gaulish root catu- ('combat') attached to uellauni ('chiefs, commandants').[1] It is probably related to the name of the 'Catalauni', a Belgic tribe dwelling in the modern Champagne region during the Roman period.[2][3]

Before the Roman conquest

The Catuvellauni are part of the Aylesford-Swarling archaeological group in Southern England often linked to Belgic Gaul and possibly to an actual Belgic conquest of the region alluded to by Caesar. John T. Koch conjectures that the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains and the modern name of Châlons-en-Champagne[4] preserves the name of an original continental tribe of Catuvellauni, a name he derives from a compound of the ancient Celtic roots *katu- ("battle") and *wer-lo ("better"), thus meaning "excelling in battle", the same source as that of the later British and Breton personal name Cadwallon.[4]

Cassivellaunus, who led the resistance to Julius Caesar's first expedition to Britain in 54 BC, is often taken to have belonged to the Catuvellauni. His tribal background is not mentioned by Caesar, but his territory, north of the Thames and to the west of the Trinovantes, corresponds to that later occupied by the Catuvellauni. The extensive earthworks at Devil's Dyke near Wheathampstead, Hertfordshire are thought to have been the tribe's original capital.

Tasciovanus was the first king to mint coins at Verlamion, beginning ca 20 BC. He appears to have expanded his power at the expense of the Trinovantes to the east, as some of his coins, ca 15–10 BC, were minted in their capital Camulodunum (modern Colchester). This advance was given up, possibly under pressure from Rome, and a later series of coins were again minted at Verulamium.

However, Camulodunum was retaken, either by Tasciovanus or by his son Cunobelinus, who succeeded him ca AD 9 and ruled for about 30 years. Little is known of Cunobelinus's life, but his name survived into British legend, culminating in William Shakespeare's play Cymbeline. Geoffrey of Monmouth says he was brought up at the court of Augustus and willingly paid tribute to Rome. Archaeology indicates increased trading and diplomatic links with the Roman Empire. Under Cunobelinus and his family, the Catuvellauni appear to have become the dominant power in south-eastern Britain. His brother Epaticcus gained territory to the south and west at the expense of the Atrebates until his death ca AD 35. The grave of the "Druid of Colchester" dates to this period, providing evidence of medical practices and technology within the Catuvellauni tribe.[5]

Three sons of Cunobelinus are known to history. Adminius, whose power-base appears from his coins to have been in Kent, was exiled by his father shortly before AD 40 according to Suetonius, prompting the emperor Caligula to mount his abortive invasion of Britain. Two other sons, Togodumnus and Caratacus, are named by Dio Cassius. No coins of Togodumnus are known, but Caratacus's rare coins suggest that he followed his uncle Epaticcus in completing the conquest of the lands of the Atrebates. It was the exile of the Atrebatic king, Verica, that prompted Claudius to launch a successful invasion, led by Aulus Plautius, in AD 43.

Dio tells us that, by this stage, Cunobelinus was dead, and Togodumnus and Caratacus led the initial resistance to the invasion in Kent. They were defeated by Plautius in two crucial battles on the rivers Medway (see Battle of the Medway) and Thames. He also tells us that the Bodunni, a tribe or kingdom who were tributary to the Catuvellauni, switched sides. This may be a misspelling of the Dobunni, who lived in Gloucestershire, and may give an indication of how far Catuvellaunian power extended. Togodumnus died shortly after the battle on the Thames. Plautius halted and sent word for the emperor to join him, and Claudius led the final advance to Camulodunum. The territories of the Catuvellauni became the nucleus of the new Roman province.

Under Roman rule

Caratacus, however, had survived, and continued to lead the resistance to the invaders. We next hear of him in Tacitus's Annals, leading the Silures and Ordovices in what is now Wales against the Roman governor Publius Ostorius Scapula. Ostorius defeated him in a set-piece battle somewhere in Ordovician territory (see Battle of Caer Caradoc) in AD 51, capturing members of his family, but Caratacus again escaped. He fled north to the Brigantes, but their queen, Cartimandua, was loyal to the Romans and handed him over in chains.

Caratacus was exhibited as a war-prize as part of a triumphal parade in Rome. He was allowed to make a speech to the Senate, and made such an impression that he and his family were freed and allowed to live in peace in Rome.

Verulamium, the Roman settlement near Verlamion, gained the status of municipium ca 50, allowing its leading magistrates to become Roman citizens. It was destroyed in the rebellion of Boudica in 60 or 61, but was soon rebuilt. Its forum and basilica were completed in 79 or 81, and were dedicated in an inscription by the governor, Gnaeus Julius Agricola, to the emperor Titus. Its theatre, the first Roman theatre in Britain, was built ca 140.

An inscription records that the civitas of the Catuvellauni were involved in the reconstruction of Hadrian's Wall, probably in the time of Septimius Severus in the early 3rd century. Saint Alban, the first British Christian martyr, was a citizen of Verulamium in the late 3rd or early 4th century, and was killed there. The city took its modern name from him. The tombstone of a woman of the Catuvellauni called Regina, freedwoman and wife of Barates, a soldier from Palmyra in Syria, was found in the 4th-century Roman fort of Arbeia in South Shields in the north-east of England.

List of leaders of the Catuvellauni

- Cassivellaunus, a military leader and possibly chieftain, often associated with the Catuvellauni c. 54 BC

- Tasciovanus, c. 20 BC – AD 9

- Cunobelinus, AD 9 – AD 40

- Togodumnus

- Caratacus

See also

References

- Delamarre 2003, p. 311.

- Schön 2006.

- Busse 2006, pp. 197–198.

- John T. Koch (ed.) Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia, Vol. I, p.357

- Games Britannia - 1. Dicing with Destiny, BBC Four, 1:05am Tuesday 8 December 2009

Bibliography

- Busse, Peter E. (2006). "Belgae". In Koch, John T. (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 195–200. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- Delamarre, Xavier (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise: Une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental (in French). Errance. ISBN 9782877723695.

- Schön, Franz (2006). "Catalauni". Brill's New Pauly.

Primary

- Julius Caesar, De Bello Gallico

- Tacitus, Annals

- Suetonius, Lives of the Twelve Caesars

- Dio Cassius, Roman History

- Ptolemy, Geography

- Geoffrey of Monmouth, Historia Regum Britanniae

Further reading

- Sheppard Frere (1998), Britannia: a History of Roman Britain, Pimlico

- John Creighton (2000), Coins and power in Late Iron Age Britain, Cambridge University Press