Celestyn Czaplic

Celestyn Czaplic (1723–1804) of the Kierdeja coat of arms was a Polish–Lithuanian szlachcic, politician, writer and a poet. Remembered for his humorous poetry and impeccable moral character, he was a deputy to numerous Sejms of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and a marshal of the Sejm of 1766. He held the offices of podczaszy, podkomorzy, and finally, from 1773, of the Master of the Hunt of the Crown. He was the recipient of the Order of Saint Stanislaus and the Order of the White Eagle.

Celestyn Czaplic | |

|---|---|

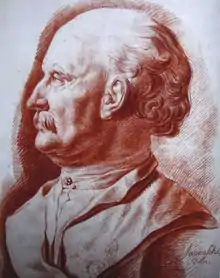

Portrait by Jan Gottlieb Jannasch | |

| Coat of arms | Kierdeja  |

| Born | April 6, 1723 |

| Died | May 23, 1804 Warsaw |

| Noble family | Czaplic |

| consort | Anna Drzewiecka h. Nałęcz |

| Issue

Tekla (d. 1820), Teresa (d. ?) | |

| Father | Ignacy Czaplic h. Kierdeja |

| Mother | Franciszka Piaskowska h. Junosza |

Biography

He was born on 6 April 1723 in Volhynia to the noble Czaplic family.[1] His father Ignaczy Czaplic, was a podstoli of Kiev in the Kiev Voivodeship.[1] He attended schools in Volhynia, and spent time at the court of the magnate and prince Antoni Lubomirski.[1] Later, he became an ally of the Czartoryski family.[1]

He became the podczaszy of Kiev in 1746.[1] He was elected a deputy to the Crown Tribunal and the Sejms of 1752, 1754, 1758, 1766 and 1767–68 (the infamous Repnin Sejm). The 1766 Sejm, lasting from October 6 to November 29, was the one where he held the position of the marshal of the Sejm, and thus it was also known as the "Czaplic's Sejm".[2][3] He became the podkomorzy of Łuck in the Volhynia Voivodeship in 1765; he was known there, as he served as a local judge for some time prior to receiving his new title and office.[1] He received the Order of Saint Stanislaus in 1766 (soon after received much praise for his marshal-ship of the 1766 Sejm).[1]

In 1767 he joined the Radom Confederation.[1] His participation in the Sejm of 1767–68, which bowed to the Russian demands, earned him condemnation from the opposition, particularly from the supporters of the Bar Confederation; despite that, he was still a popular figure, and highly considered by the king.[1] In 1773 he received the office and title of Master of the Hunt of the Crown (łowczy koronny), which he held to 1783.[1][2] Between 1778–80 he was a member of the Permanent Council.[1] He unsuccessfully campaigned for the position of the Deputy Chancellor of the Crown.[1] During the Great Sejm of 1788–1792 he served as a member of the Military Commission.[2]

He also participated in the "Thursday Dinners" organized by king Stanisław August Poniatowski.[1]

He was a knight of the Order of the White Eagle from 1775.[1]

Friend of the dramatist Franciszek Bohomolec, he has been described as "open and friendly", "extremely jolly and witty", also well versed in sarcasm.[1] He was interested in sciences, and had a sizable library.[1] He was also famous among his contemporaries for his absent-mindedness, but also for his righteousness and impeccable moral character; it is said then when contemporaries at the royal court in Warsaw were considering questions of morality, they would ask themselves "What would Czaplic think of that?"[1][4] This became a mildly popular proverb in Poland around the time of his life.[5]

As a writer and poet he has authored fairy tales, idyls, and similar forms of light poetry, some of it published anonymously.[2] He was known to improvise humorous poems and songs on the fly, which he would often perform himself, accompanying himself on a violin.[6] He might have been the author of a popular festive song, Kurdesz nad kurdeszami, however his authorship of it is not certain.[1][6][7][8]

He married Anna Drzewicka, and they had two daughters, Tekla and Teresa.[1] He died on May 23, 1804 in Warsaw, where he spent the last decade of his life.[1]

External links

Further reading

- T. Mikulski: „Kurdesz nad kurdeszami!" Zagadnienie tekstu i autorstwa. „Pamiętnik Literacki" 1959

References

- Samuel Orgelbrand (1861). Encyklopedyja powszechna. Orgelbrand. pp. 140–142. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- Jan Zahorski (1901). Dzieje Polski chronologicznie ułożone. Druk Warszawskiego Towarzystwa Akcyjnego Artystyczno Wydawniczego. p. 224. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- Julian Krzyżanowski (1960). Mądrej głowie dość dwie słowie. Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy. p. 50. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- Kasa imienia Mianowskiego, instytut popierania nauki, Warsaw (1894). Ksiega przyslów: przypowieści i wrażeń przyslowiowych polskich. Druk E. Skiwskiego. p. 75. Retrieved 23 October 2011.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Jerzy Kowecki; Hanna Szwankowska; Andrzej Zahorski (1972). Warszawa XVIII [i.e. osiemnastego] wieku. Państwowe Wydawn. Naukowe. p. 75. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- Stefan Sutkowski (2004). The history of music in Poland: 1750–1830. The Classical Era. Sutkowski Edition Warsaw. p. 305. ISBN 978-83-917035-3-3. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- Zygmunt Gloger (1902). Encyklopedja staropolska ilustrowana. Druk P. Laskauere i. W. Babickiego. p. 121. Retrieved 23 October 2011.