Cheerleading

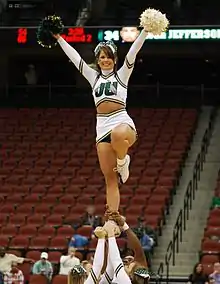

Cheerleading is an activity in which the participants (called "cheerleaders") cheer for their team as a form of encouragement. It can range from chanting slogans to intense physical activity. It can be performed to motivate sports teams, to entertain the audience, or for competition. Cheerleading routines typically range anywhere from one to three minutes, and contain components of tumbling, dance, jumps, cheers, and stunting.

Cheerleading originated in the United States, and remains predominantly in America, with an estimated 3.85 million participants as of 2017. [1] The global presentation of cheerleading was led by the 1997 broadcast of ESPN's International cheerleading competition, and the worldwide release of the 2000 film Bring It On. The International Cheer Union (ICU) now claims 116 member nations with an estimated 7.5 million participants worldwide.[2] The sport has gained a lot of traction in Australia, Canada, China, Colombia, Finland, France, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom with popularity continuing to grow as sport leaders pursue Olympic status.[3]

History

Before organized cheerleading

Cheerleading began during the late 18th century with the rebellion of male students.[4] After the American Revolutionary War, students experienced harsh treatment from teachers. In response to faculty's abuse, college students violently acted out. The undergraduates began to riot, burn down buildings located on their college campuses, and assault faculty members. As a more subtle way to gain independence, however, students invented and organized their own extracurricular activities outside their professors' control. This brought about American sports, beginning first with collegiate teams.[5]

In the 1860s, students from Great Britain began to cheer and chant in unison for their favorite athletes at sporting events. Soon, that gesture of support crossed overseas to America.[6]

On November 6, 1869, the United States witnessed its first intercollegiate football game. It took place between Princeton University and Rutgers University, and marked the day the original "Sis Boom Rah!" cheer was shouted out by student fans.[7][8]

Beginning of organized cheerleading

Organized cheerleading started as an all-male activity.[9] As early as 1877, Princeton University had a "Princeton Cheer", documented in the February 22, 1877, March 12, 1880, and November 4, 1881, issues of The Daily Princetonian.[10][11][12] This cheer was yelled from the stands by students attending games, as well as by the athletes themselves. The cheer, "Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah! Tiger! S-s-s-t! Boom! A-h-h-h!" remains in use with slight modifications today, where it is now referred to as the "Locomotive".[13]

Princeton class of 1882 graduate Thomas Peebles moved to Minnesota in 1884. He transplanted the idea of organized crowds cheering at football games to the University of Minnesota.[14][15] The term "Cheer Leader" had been used as early as 1897, with Princeton's football officials having named three students as Cheer Leaders: Thomas, Easton, and Guerin from Princeton's classes of 1897, 1898, and 1899, respectively, on October 26, 1897. These students would cheer for the team also at football practices, and special cheering sections were designated in the stands for the games themselves for both the home and visiting teams.[16][17]

It was not until 1898 that University of Minnesota student Johnny Campbell directed a crowd in cheering "Rah, Rah, Rah! Ski-u-mah, Hoo-Rah! Hoo-Rah! Varsity! Varsity! Varsity, Minn-e-So-Tah!", making Campbell the very first cheerleader.

November 2, 1898 is the official birth date of organized cheerleading. Soon after, the University of Minnesota organized a "yell leader" squad of six male students, who still use Campbell's original cheer today.[18] In 1903, the first cheerleading fraternity, Gamma Sigma, was founded.[19]

.jpg.webp)

Female participation

In 1923, at the University of Minnesota, women were permitted to participate in cheerleading.[7][20] However, it took time for other schools to follow. In the late 1920s, many school manuals and newspapers that were published still referred to cheerleaders as "chap," "fellow," and "man".[21] Women cheerleaders were overlooked until the 1940s when collegiate men were drafted for World War II, creating the opportunity for more women to make their way onto sporting event sidelines.[22] As noted by Kieran Scott in Ultimate Cheerleading: "Girls really took over for the first time."[23] An overview written on behalf of cheerleading in 1955 explained that in larger schools, "occasionally boys as well as girls are included,", and in smaller schools, "boys can usually find their place in the athletic program, and cheerleading is likely to remain solely a feminine occupation."[24] During the 1950s, female participation in cheerleading continued to grow and by the 1970s, it was girls primarily cheering at public school games.[25] Cheerleading could be found at almost every school level across the country, even pee wee and youth leagues began to appear.[26][27]

In 1975, it was estimated by a man named Randy Neil that over 500,000 students actively participated in American cheerleading from elementary school to the collegiate level. He also approximated that ninety-five percent of cheerleaders within America were female.[28] As of 2005, overall statistics show around 97% of all modern cheerleading participants are female, although at the collegiate level, cheerleading is co-ed with about 50% of participants being male.[29]

Cheerleading's popularity grows

In 1949, Lawrence "Herkie" Herkimer, of Dallas, Texas, a former cheerleader at Southern Methodist University, administered a cheerleading education clinic in Huntsville, Texas, with 52 girls in attendance.[29] The clinic was so popular, Herkimer was asked to hold a second, where 350 young women were in attendance. Herkimer then founded the National Cheerleaders Association (NCA) to help grow the activity and provide cheerleading education to schools around the country. By the 1960s, college cheerleaders employed by the NCA were hosting workshops across the nation, teaching fundamental cheer skills to tens of thousands of high-school-age girls.[30] Herkimer also contributed many notable firsts to cheerleading: the founding of a cheerleading uniform supply company, inventing the herkie jump (where one leg is bent towards the ground as if kneeling and the other is out to the side as high as it will stretch in toe-touch position),[31] and creating the "Spirit Stick".[19] In 1965, Fred Gastoff invented the vinyl pom-pom, which was introduced into competitions by the International Cheerleading Foundation (ICF, now the World Cheerleading Association, or WCA). Organized cheerleading competitions began to pop up with the first ranking of the "Top Ten College Cheerleading Squads" and "Cheerleader All America" awards given out by the ICF in 1967. In 1978, America was introduced to competitive cheerleading by the first broadcast of Collegiate Cheerleading Championships on CBS.[18][19]

Development of professional cheerleading

%252C_in_1983_(6370287).jpg.webp)

In the 1950s, the formation of professional cheerleading started. The first recorded cheer squad in National Football League (NFL) history was for the Baltimore Colts.[6][32] Professional cheerleaders put a new perspective on American cheerleading. Women were selected for two reasons: visual sex appeal, and the ability to dance. Women were exclusively chosen because men were the targeted marketing group.[33] The Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders soon gained the spotlight with their revealing outfits and sophisticated dance moves, debuting in the 1972–1973 season, but were first widely seen in Super Bowl X (1976). These pro squads of the 1970s established cheerleaders as "American icons of wholesome sex appeal."[20] By 1981, a total of seventeen Nation Football League teams had their own cheerleaders. The only teams without NFL cheerleaders at this time were New Orleans, New York, Detroit, Cleveland, Denver, Minnesota, Pittsburgh, San Francisco, and San Diego. Professional cheerleading eventually spread to soccer and basketball teams as well.[33]

Modern advancements in cheerleading

The 1980s saw the beginning of modern cheerleading, adding difficult stunt sequences and gymnastics into routines. All-star teams, or those not affiliated with a school, popped up, and eventually led to the creation of the U.S. All Star Federation (USASF). ESPN first broadcast the National High School Cheerleading Competition nationwide in 1983. Cheerleading organizations such as the American Association of Cheerleading Coaches and Advisors (AACCA), founded in 1987, started applying universal safety standards to decrease the number of injuries and prevent dangerous stunts, pyramids, and tumbling passes from being included in the cheerleading routines.[35] In 2003, the National Council for Spirit Safety and Education (NCSSE) was formed to offer safety training for youth, school, all-star, and college coaches. The NCAA now requires college cheer coaches to successfully complete a nationally recognized safety-training program.

Even with its athletic and competitive development, cheerleading at the school level has retained its ties to its spirit leading traditions. Cheerleaders are quite often seen as ambassadors for their schools, and leaders among the student body. At the college level, cheerleaders are often invited to help at university fundraisers and events.[36]

Cheerleading is very closely associated with American football and basketball. Sports such as association football (soccer), ice hockey, volleyball, baseball, and wrestling will sometimes sponsor cheerleading squads. The ICC Twenty20 Cricket World Cup in South Africa in 2007 was the first international cricket event to have cheerleaders. The Florida Marlins were the first Major League Baseball team to have a cheerleading team. Debuting in 2003, the "Marlin Mermaids" gained national exposure, and have influenced other MLB teams to develop their own cheer/dance squads.[37]

Types of teams in the United States today

School-sponsored

Most American middle schools, high schools, and colleges have organized cheerleading squads. Some colleges even offer cheerleading scholarships for students. A school cheerleading team may compete locally, regionally, or nationally, but their main purpose is typically to cheer for sporting events and encourage audience participation. Cheerleading is quickly becoming a year-round activity, starting with tryouts during the spring semester of the preceding school year. Teams may attend organized summer cheerleading camps and practices to improve skills and create routines for competition.

In addition to supporting their schools’ football or other sports teams, student cheerleaders may compete with recreational-style routine at competitions year-round.

Middle school

Middle school cheerleading evolved shortly after high school squads were created. In middle school, cheerleading squads serve the same purpose, but often follow a modified set of rules from high school squads. Squads can cheer for basketball teams, football teams, and other sports teams in their school. Squads may also perform at pep rallies and compete against other local schools from the area. Cheerleading in middle school sometimes can be a two-season activity: fall and winter. However, many middle school cheer squads will go year-round like high school squads. Middle school cheerleaders use the same cheerleading movements as their older counterparts, yet may perform less extreme stunts and tumbling elements, depending on the rules in their area.

High school

In high school, there are usually two squads per school: varsity and a junior varsity. High school cheerleading contains aspects of school spirit as well as competition. These squads have become part of a year-round cycle. Starting with tryouts in the spring, year-round practice, cheering on teams in the fall and winter, and participating in cheerleading competitions. Most squads practice at least three days a week for about two hours each practice during the summer. Many teams also attend separate tumbling sessions outside of practice. During the school year, cheerleading is usually practiced five- to six-days-a-week. During competition season, it often becomes seven days with practice twice a day sometimes. The school spirit aspect of cheerleading involves cheering, supporting, and "hyping up" the crowd at football games, basketball games, and even at wrestling meets. Along with this, cheerleaders usually perform at pep rallies, and bring school spirit to other students. In May 2009, the National Federation of State High School Associations released the results of their first true high school participation study. They estimated that the number of high school cheerleaders from public high schools is around 394,700.[38]

There are different cheerleading organizations that put on competitions; some of the major ones include state and regional competitions. Many high schools will often host cheerleading competitions, bringing in IHSA judges. The regional competitions are qualifiers for national competitions, such as the UCA (Universal Cheerleaders Association) in Orlando, Florida every year.[39] Many teams have a professional choreographer that choreographs their routine in order to ensure they are not breaking rules or regulations and to give the squad creative elements.

College

Most American universities have a cheerleading squad to cheer for football, basketball, volleyball, and soccer. Most college squads tend to be larger coed teams, although in recent years; all-girl squads and smaller college squads have increased rapidly.

College squads perform more difficult stunts which include multi-level pyramids, as well as flipping and twisting basket tosses.

Not only do college cheerleaders cheer on the other sports at their university, many teams at universities compete with other schools at either UCA College Nationals or NCA College Nationals. This requires the teams to choreograph a 2-minute and 30 second routine that includes elements of jumps, tumbling, stunting, basket tosses, and pyramids. Winning one of these competitions is a very prestigious accomplishment, and is seen as another national title for most schools.

Youth leagues and athletic associations

Organizations that sponsor youth cheer teams usually sponsor either youth league football or basketball teams as well. This allows for the two, under the same sponsor, to be intermingled. Both teams have the same mascot name and the cheerleaders will perform at their football or basketball games. Examples of such sponsors include Pop Warner, American Youth Football, and the YMCA.[40] The purpose of these squads is primarily to support their associated football or basketball players, but some teams do compete at local or regional completions. The Pop Warner Association even hosts a national championship each December for teams in their program who qualify.

All-star or club cheerleading

”All-star” or club cheerleading differs from school or sideline cheerleading because all-star teams focus solely on performing a competition routine and not on leading cheers for other sports teams. All-star cheerleaders are members of a privately owned gym or club which they typically pay dues or tuition to, similar to a gymnastics gym.

During the early 1980s, cheerleading squads not associated with a school or sports league, whose main objective was competition, began to emerge. The first organization to call themselves all-stars were the Q94 Rockers from Richmond, Virginia, founded in 1982.[41] All-star teams competing prior to 1987 were placed into the same divisions as teams that represented schools and sports leagues. In 1986, the National Cheerleaders Association (NCA) addressed this situation by creating a separate division for teams lacking a sponsoring school or athletic association, calling it the All-Star Division and debuting it at their 1987 competitions. As the popularity of this type of team grew, more and more of them were formed, attending competitions sponsored by many different organizations and companies, each using its own set of rules, regulations, and divisions. This situation became a concern to coaches and gym owners, as the inconsistencies caused coaches to keep their routines in a constant state of flux, detracting from time that could be better utilized for developing skills and providing personal attention to their athletes. More importantly, because the various companies were constantly vying for a competitive edge, safety standards had become more and more lax. In some cases, unqualified coaches and inexperienced squads were attempting dangerous stunts as a result of these expanded sets of rules.[42]

The United States All Star Federation (USASF) was formed in 2003 by the competition companies to act as the national governing body for all star cheerleading and to create a standard set of rules and judging criteria to be followed by all competitions sanctioned by the Federation. Eager to grow the sport and create more opportunities for high-level teams, The USASF hosted the first Cheerleading Worlds on April 24, 2004.[42] At the same time, cheerleading coaches from all over the country organized themselves for the same rule making purpose, calling themselves the National All Star Cheerleading Coaches Congress (NACCC). In 2005, the NACCC was absorbed by the USASF to become their rule making body.[41] In late 2006, the USASF facilitated the creation of the International All-Star Federation (IASF), which now governs club cheerleading worldwide.

As of 2020, all-star cheerleading, as sanctioned by the USASF, involves a squad of 5–36 females and males. All-star cheerleaders are placed into divisions, which are grouped based upon age, size of the team, gender of participants, and ability level. The age groups vary from under 4 years of age to 18 years and over. The squad prepares year-round for many different competition appearances, but they actually perform only for up to 2½ minutes during their team's routine. The numbers of competitions a team participates in varies from team to team, but generally, most teams tend to participate in six to ten competitions a year. These competitions include locals or regionals, which normally take place in school gymnasiums or local venues, nationals, hosted in large venues all around the U.S., and the Cheerleading Worlds, which takes place at Walt Disney World in Orlando, Florida. During a competition routine, a squad performs carefully choreographed stunting, tumbling, jumping, and dancing to their own custom music. Teams create their routines to an eight-count system and apply that to the music so that the team members execute the elements with precise timing and synchronization.

All-star cheerleaders compete at competitions hosted by private event production companies, the foremost of these being Varsity Spirit. Varsity Spirit is the parent company for many subsidiaries including The National Cheerleader's Association, The Universal Cheerleader's Association, AmeriCheer, Allstar Challenge, and JamFest, among others. Each separate company or subsidiary typically hosts their own local and national level competitions. This means that many gyms within the same area could be state and national champions for the same year and never have competed against each other. Currently, there is no system in place that awards only one state or national title.

Judges at a competition watch closely for illegal skills from the group or any individual member. Here, an illegal skill is something that is not allowed in that division due to difficulty or safety restrictions. They look out for deductions, or things that go wrong, such as a dropped stunt or a tumbler who doesn’t stick a landing. More generally, judges look at the difficulty and execution of jumps, stunts and tumbling, synchronization, creativity, the sharpness of the motions, showmanship, and overall routine execution.

If a level 6 or 7 team places high enough at selected USASF/IASF sanctioned national competitions, they could earn a place at the Cheerleading Worlds and compete against teams from all over the world, as well as receive money for placing.[3] For elite level cheerleaders, The Cheerleading Worlds is the highest level of competition to which they can aspire, and winning a world championship title is an incredible honor.

Professional

Professional cheerleaders and dancers cheer for sports such as football, basketball, baseball, wrestling, or hockey. There are only a small handful of professional cheerleading leagues around the world; some professional leagues include the NBA Cheerleading League, the NFL Cheerleading League, the CFL Cheerleading League, the MLS Cheerleading League, the MLB Cheerleading League, and the NHL Ice Girls. Although professional cheerleading leagues exist in multiple countries, there are no Olympic teams.[43]

In addition to cheering at games and competing, professional cheerleaders also, as teams, can often do a lot of philanthropy and charity work, modeling, motivational speaking, television performances, and advertising.[44]

Associations, federations, and organizations

International Cheer Union (ICU):[45] Established on April 26, 2004, the ICU is recognized by the SportAccord as the world governing body of cheerleading and the authority on all matters with relation to it. Including participation from its 105-member national federations reaching 3.5 million athletes globally, the ICU continues to serve as the unified voice for those dedicated to cheerleading's positive development around the world.

Following a positive vote by the SportAccord General Assembly on May 31, 2013, in Saint Petersburg, the International Cheer Union (ICU) became SportAccord's 109th member, and SportAccord's 93rd international sports federation to join the international sports family. In accordance with the SportAccord statutes, the ICU is recognized as the world governing body of cheerleading and the authority on all matters related to it.

As of the 2016–17 season, the ICU has introduced a Junior aged team (12-16) to compete at the Cheerleading Worlds, because cheerleading is now in provisional status to become a sport in the Olympics. For cheerleading to one day be in the Olympics, there must be a junior and senior team that competes at the world championships. The first junior cheerleading team that was selected to become the junior national team was Eastside Middle School, located in Mount Washington Kentucky and will represent the United States in the inaugural junior division at the world championships.[46]

The ICU holds training seminars for judges and coaches, global events and the World Cheerleading Championships. The ICU is also fully applied to the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and is compliant under the code set by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA).

International Federation of Cheerleading (IFC):[47] Established on July 5, 1998, the International Federation of Cheerleading (IFC) is a non-profit federation based in Tokyo, Japan, and is a world governing body of cheerleading, primarily in Asia. The IFC objectives are to promote cheerleading worldwide, to spread knowledge of cheerleading, and to develop friendly relations among the member associations and federations.

USA Cheer The USA Federation for Sport Cheering (USA Cheer) was established in 2007 to serve as the national governing body for all types of cheerleading in the United States and is recognized by the ICU.[48] "The USA Federation for Sport Cheering is a not-for profit 501(c)(6) organization that was established in 2007 to serve as the National Governing Body for Sport Cheering in the United States. USA Cheer exists to serve the cheer community, including club cheering (all star) and traditional school based cheer programs, and the growing sport of STUNT. USA Cheer has three primary objectives: help grow and develop interest and participation in cheer throughout the United States; promote safety and safety education for cheer in the United States; and represent the United States of America in international cheer competitions."[48] In March 2018, they absorbed the American Association of Cheerleading Coaches and Advisors (AACCA) and now provide safety guidelines and training for all levels of cheerleading.[49] Additionally, they organize the USA National Team.

Competitions and companies

Asian Thailand Cheerleading Invitational (ATCI):[50] Organised by the Cheerleading Association of Thailand (CAT) in accordance with the rules and regulations of the International Federation of Cheerleading (IFC). The ATCI is held every year since 2009. At the ATCI, many teams from all over Thailand compete, joining them are many invited neighbouring nations who also send cheer squads.

Cheerleading Asia International Open Championships (CAIOC): Hosted by the Foundation of Japan Cheerleading Association (FJCA) in accordance with the rules and regulations of the IFC. The CAIOC has been a yearly event since 2007. Every year, many teams from all over Asia converge in Tokyo to compete.[51]

Cheerleading World Championships (CWC):[52] Organised by the IFC. The IFC is a non-profit organisation founded in 1998 and based in Tokyo, Japan. The CWC has been held every two years since 2001, and to date, the competition has been held in Japan, the United Kingdom, Finland, Germany, and Hong Kong. The 6th CWC was held at the Hong Kong Coliseum on November 26–27, 2011.[53]

ICU World Championships:[54] The International Cheer Union currently encompasses 105 National Federations from countries across the globe. Every year, the ICU host the World Cheerleading Championship. This competition uses a more collegiate style performance and rulebook. Countries assemble and send only one team to represent them.

National Cheerleading Championships (NCC):[55] The NCC is the annual IFC-sanctioned national cheerleading competition in Indonesia organised by the Indonesian Cheerleading Community (ICC).[56] Since NCC 2010, the event is now open to international competition, representing a significant step forward for the ICC. Teams from many countries such as Japan, Thailand, the Philippines, and Singapore participated in the ground breaking event.

Pan-American Cheerleading Championships (PCC):[57] The PCC was held for the first time in 2009 in the city of Latacunga, Ecuador and is the continental championship organised by the Pan-American Federation of Cheerleading (PFC). The PFC, operating under the umbrella of the IFC, is the non-profit continental body of cheerleading whose aim it is to promote and develop cheerleading in the Americas. The PCC is a biennial event, and was held for the second time in Lima, Peru, in November 2010.

USASF/IASF Worlds:[58][59] Many United States cheerleading organizations form and register the not-for-profit entity the United States All Star Federation (USASF) and also the International All Star Federation (IASF) to support international club cheerleading and the World Cheerleading Club Championships. The first World Cheerleading Championships, or Cheerleading Worlds, were hosted by the USASF/IASF at the Walt Disney World Resort and taped for an ESPN global broadcast in 2004. This competition is only for All-Star/Club cheer. Only level 6 and 7 teams may attend and must receive a bid from a partner company.

Varsity:[60] Varsity Spirit, a branch of Varsity Brands is a parent company which, over the past 10 years, has absorbed or bought most other cheerleading event production companies. The following is a list of subsidiary competition companies owned by Varsity Spirit:[61]

- All Star Challenge

- All Star Championships

- All Things Cheer

- Aloha Spirit Championships

- America's Best Championships

- American Cheer and Dance

- American Cheer Power

- American Cheerleaders Association

- AmeriCheer:[62] Americheer was founded in 1987 by Elizabeth Rossetti. It is the parent company to Ameridance and Eastern Cheer and Dance Association. In 2005, Americheer became one of the founding members of the NLCC. This means that Americheer events offer bids to The U.S. Finals: The Final Destination. AmeriCheer InterNational Championship competition is held every March at the Walt Disney World Resort in Orlando, Florida.

- Athletic Championships

- Champion Cheer and Dance

- Champion Spirit Group

- Cheer LTD

- CHEERSPORT: CHEERSPORT was founded in 1993 by all star coaches who believed they could conduct competitions that would be better for the athletes, coaches and spectators. Their main event is CHEERSPORT Nationals, held each February at the Georgia World Congress Center in Atlanta, Georgia

- CheerStarz

- COA Cheer and Dance

- Coastal Cheer and Dance

- Encore Championships

- GLCC Events

- Golden State Spirit Association

- The JAM Brands:[63] The JAM Brands, headquartered in Louisville, Kentucky, provides products and services for the cheerleading and dance industry. It was previously made up of approximately 12 different brands that produce everything from competitions to camps to uniforms to merchandise and apparel, but is now owned by the parent company Varsity. JAMfest, the original brand of The JAM Brands, has been around since 1996 and was founded by Aaron Flaker and Emmitt Tyler.

- Mardi Gras Spirit Events

- Mid Atlantic Championships

- Nation's Choice

- National Cheerleader's Association: The NCA was founded in 1948 by Lawrence Herkimer. Every year, the NCA hosts a variety of competitions all across the United States, most notably the NCA High School Cheerleading Nationals and the NCA All-Star Cheerleading Nationals in Dallas, Texas. They also host the NCA/NDA Collegiate Cheer & Dance Championship in Daytona Beach, Florida. In addition to competitions they also provide summer camps for school cheerleaders.

- One Up Championships

- PacWest

- Sea to Sky

- Spirit Celebration

- Spirit Cheer

- Spirit Sports

- Spirit Unlimited

- Spirit Xpress

- The American Championships

- The U.S. Finals: This event was formerly hosted by Nation's Leading Cheer Companies which was a multi brand company, partnered with other companies such as: Americheer/Ameridance, American Cheer & Dance Academy, Eastern Cheer & Dance Association, and Spirit Unlimited before they were all acquired by Varsity. Every year, starting in 2006, the NLCC hosted The US Finals: The Final Destination of Cheerleading and Dance. Every team that attends must qualify and receive a bid at a partner company's competition. In May 2008, the NLCC and The JAM Brands announced a partnership to produce The U.S. Finals - Final Destination. This event is still produced under the new parent company, Varsity. There are nine Final Destination locations across the country. After the regional events, videos of all the teams that competed are sent to a new panel of judges and rescored to rank teams against those against whom they may never have had a chance to compete.

- Universal Cheerleaders Association:[64] Universal Cheerleaders Association was founded in 1974 by Jeff Webb. Since 1980, UCA has hosted the National High School Cheerleading Championship in Walt Disney World Resort. They also host the National All-Star Cheerleading Championship, and the College Cheerleading National Championship at Walt Disney World Resort. All of these events air on ESPN.

- United Spirit Association:[65] In 1950, Robert Olmstead directed his first summer training camp, and USA later sprouted from this. USA's focus is on the game day experience as a way to enhance audience entertainment. This focus led to the first American football half-time shows to reach adolescences from around the world and expose them to American style cheerleading. USA provides competitions for cheerleading squads without prior qualifications needed in order to participate. The organization also allows the opportunity for cheerleaders to become an All-American, participate in the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade, and partake in London's New Year's Day Parade and other special events much like UCA and NCA allow participants to do.

- Universal Spirit Association

- World Spirit Federation

Title IX sports status

In the United States, the designation of a "sport" is important because of Title IX. There is a large debate on whether or not cheerleading should be considered a sport for Title IX (a portion of the United States Education Amendments of 1972 forbidding discrimination under any education program on the basis of sex) purposes. The Office for Civil Rights (OCR) issued memos and letters to schools that cheerleading, both sideline and competitive, may not be considered "athletic programs" for the purposes of Title IX.[66] Supporters consider cheerleading, as a whole, a sport, citing the heavy use of athletic talents[67][68] while critics see it as a physical activity because a "sport" implies a competition among all squads and not all squads compete, along with subjectivity of competitions where—as with gymnastics, diving, and figure skating—scores are assessed based on human judgment and not an objective goal or measurement of time.[69][70][71]

On January 27, 2009, in a lawsuit involving an accidental injury sustained during a cheerleading practice, the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled that cheerleading is a full-contact sport in that state, not allowing any participants to be sued for accidental injury.[72][73] In contrast, on July 21, 2010, in a lawsuit involving whether college cheerleading qualified as a sport for purposes of Title IX, a federal court, citing a current lack of program development and organization, ruled that it is not a sport at all.[74]

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) does not recognize cheerleading as a sport.[75] In 2014, the American Medical Association adopted a policy that, as the leading cause of catastrophic injuries of female athletes both in high school and college, cheerleading should be considered a sport.[76]

Dangers of cheerleading

Cheerleading carries the highest rate of catastrophic injuries to girl athletes in sports.[77] The risks of cheerleading were highlighted when Kristi Yamaoka, a cheerleader for Southern Illinois University, suffered a fractured vertebra when she hit her head after falling from a human pyramid.[78][79] She also suffered from a concussion, and a bruised lung.[80] The fall occurred when Yamaoka lost her balance during a basketball game between Southern Illinois University and Bradley University at the Savvis Center in St. Louis on March 5, 2006.[80] The fall gained "national attention",[80] because Yamaoka continued to perform from a stretcher as she was moved away from the game.[80] Yamaoka has since made a full recovery.

The accident caused the Missouri Valley Conference to ban its member schools from allowing cheerleaders to be "launched or tossed and from taking part in formations higher than two levels" for one week during a women's basketball conference tournament, and also resulted in a recommendation by the NCAA that conferences and tournaments do not allow pyramids two and one half levels high or higher, and a stunt known as basket tosses, during the rest of the men's and women's basketball season.[81] On July 11, 2006, the bans were made permanent by the AACCA rules committee:

The committee unanimously voted for sweeping revisions to cheerleading safety rules, the most major of which restricts specific upper-level skills during basketball games. Basket tosses, 2½ high pyramids, one-arm stunts, stunts that involve twisting or flipping, and twisting tumbling skills may be performed only during halftime and post-game on a matted surface and are prohibited during game play or time-outs.[81]

Another major cheerleading accident was the death of Lauren Chang. Chang died on April 14, 2008 after competing in a competition where her teammate had kicked her so hard in the chest that her lungs collapsed.[82]

Of the United States' 2.9 million female high school athletes, only 3% are cheerleaders, yet cheerleading accounts for nearly 65% of all catastrophic injuries in girls' high school athletics.[83] The NCAA does not recognize cheerleading as a collegiate sport; there are no solid numbers on college cheerleading, yet when it comes to injuries, 67% of female athlete injuries at the college level are due to cheerleading mishaps. Another study found that between 1982 and 2007, there were 103 fatal, disabling, or serious injuries recorded among female high school athletes, with the vast majority (67) occurring in cheerleading.[84]

In the early 2000s, cheerleading was considered one of the most dangerous school activities. The main source of injuries comes from stunting, also known as pyramids. These stunts are performed at games and pep rallies, as well as competitions. Sometimes competition routines are focused solely around the use of difficult and risky stunts. These stunts usually include a flyer (the person on top), along with one or two bases (the people on the bottom), and one or two spotters in the front and back on the bottom. The most common cheerleading related injury is a concussion. 96% of those concussions are stunt related.[77] Others injuries are: sprained ankles, sprained wrists, back injuries, head injuries (sometimes concussions), broken arms, elbow injuries, knee injuries, broken noses, and broken collarbones.[85][86] Sometimes, however, injuries can be as serious as whiplash, broken necks, broken vertebrae, and death.[87]

The journal Pediatrics has reportedly said that the number of cheerleaders suffering from broken bones, concussions, and sprains has increased by over 100 percent between the years of 1990 and 2002, and that in 2001, there were 25,000 hospital visits reported for cheerleading injuries dealing with the shoulder, ankle, head, and neck.[88] Meanwhile, in the US, cheerleading accounted for 65.1% of all major physical injuries to high school females, and to 66.7% of major injuries to college students due to physical activity from 1982 to 2007, with 22,900 minors being admitted to hospital with cheerleading-related injuries in 2002.[89][90]

In October 2009, the American Association of Cheerleading Coaches and Advisors (AACCA), a subsidiary of Varsity Brands, released a study that analyzed the data from emergency room visits of all high school athletes. The study asserted that contrary to many perceptions, cheerleading injuries are in line with female sports.[91]

Cheerleading (for both girls and boys) was one of the sports studied in the Pediatric Injury Prevention, Education and Research Program of the Colorado School of Public Health in 2009/10–2012/13.[92] Data on cheerleading injuries is included in the report for 2012–13.[93]

In popular culture

- Film and television

The revamped and provocative Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders of the 1970s—and the many imitators that followed—firmly established the cheerleader as an American icon of wholesome sex appeal. In response, a new subgenre of exploitation films suddenly sprang up with titles such as The Cheerleaders (1972), The Swinging Cheerleaders (1974), Revenge of the Cheerleaders (1975), The Pom Pom Girls (1976), Satan's Cheerleaders (1977), Cheerleaders Beach Party (1978), Cheerleaders's Wild Weekend (1979), and Gimme an 'F' (1984). In addition to R-rated sex comedies and horror films, cheerleaders became a staple of the adult film industry, starting with Debbie Does Dallas (1978) and its four sequels.

On television, the made-for-TV movie The Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders (which aired January 14, 1979) starring Jane Seymour was a highly rated success, spawning the 1980 sequel The Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders II.

The Dallas squad was in high demand during the late 1970s with frequent appearances on network specials, awards shows, variety programs, commercials, the game show Family Feud and TV series such as The Love Boat. The sci-fi sitcom Mork & Mindy also based a 1979 episode around the Denver Broncos cheerleaders with Mork (Robin Williams) trying out for the squad.

The Positively True Adventures of the Alleged Texas Cheerleader-Murdering Mom (1993) is a TV movie which dramatized the true story of Wanda Holloway, the Texas mother whose obsession with her daughter's cheerleading career made headline news. Another lurid TV movie based on a true story, Fab Five: The Texas Cheerleader Scandal was produced in 2008. In 1999's American Beauty, Lester Burnham's suburban midlife crisis begins when he becomes infatuated with his daughter Jane's vain cheerleader friend, Angela Hayes, after seeing her perform a half-time dance routine at a high school basketball game.

Cheerleading's increasing popularity in recent decades has made it a prominent feature in high-school themed movies and television shows. The 2000 film Bring It On, about a San Diego high school cheerleading squad called "The Toros", starred real-life former cheerleader Kirsten Dunst. Bring It On was a surprise hit and earned nearly $70 million domestically. It spawned five direct-to-video sequels: Bring It On Again (2004), Bring It On: All or Nothing (2006), Bring It On: In It to Win It (2007), Bring It On: Fight to the Finish (2009) and Bring It On: Worldwide Cheersmack (2017). The first Bring It On was followed by the cheerleader caper-comedy, Sugar & Spice (2001) and a string of campy horror/action films such as Cheerleader Ninjas (2002), Cheerleader Autopsy, Cheerleader Massacre (both 2003), Chainsaw Cheerleaders, and Ninja Cheerleaders (both 2008).

In 2006, Hayden Panettiere, star of Bring It On: All or Nothing, took another cheerleading role as Claire Bennet, the cheerleader with an accelerated healing factor on NBC's hit sci-fi TV series Heroes, launching cheerleading back into the limelight of pop culture. Claire was the main focus of the show's first story arc, featuring the popular catchphrase, "Save the cheerleader, save the world". Her prominent, protagonist role in Heroes was supported by a strong fan-base and provided a positive image for high school cheerleading.[94] In the second season of the show, the mean head cheerleader character Debbie Marshall, played by Dianna Agron was introduced as a foil to Claire.[95]

In 2009, Panettiere starred again as a cheerleader, this time as Beth Cooper in the film adaptation of the novel I Love You, Beth Cooper.

In 2006, the reality show Cheerleader Nation was featured on the Lifetime television channel. Cheerleader Nation is a 60-minute television series based on the Paul Laurence Dunbar High School cheerleading team's ups and downs on the way to nationals, of which they are the three-time champions. The show also believes that cheerleading is tough. The show takes place in Lexington, Kentucky.

The 2007 series Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders: Making the Team shows the process of getting on the pro squad of the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders. Everything from initial tryouts to workout routines and the difficulties involved is shown.

Fired Up!, a teen comedy about cheerleading camp, was released by Screen Gems in 2009. In the supernatural horror-comedy Jennifer's Body (2009), Megan Fox plays a demonically possessed high school cheerleader. Also that year, Universal Pictures signed music video and film director Bille Woodruff (Barbershop, Honey) to direct the fifth film in the Bring It On series titled Bring It On: Fight to the Finish. The film stars Christina Milian (who previously played cheerleaders in Love Don't Cost a Thing and Man of the House) and Rachelle Brook Smith, and was released directly to DVD and Blu-ray on September 1, 2009.

The television series Glee (2009-2015) featured Dianna Agron in another cheerleading role as Quinn Fabray, the captain of her high school cheerleading squad, the Cheerios. Quinn becomes pregnant, leading to her expulsion from the squad, but two of the other Cheerios, Santana Lopez and Brittany Pierce also feature heavily in the show. In the episode "The Power of Madonna", Kurt Hummel joins the Cheerios along with Mercedes Jones.

The CW Television Network created the short-lived Hellcats series (2010–11). This drama was about the ups and downs of being a college cheerleader. It starred Aly Michalka as Marty (a former gymnast forced to become a cheerleader after her academic scholarship is canceled) and Ashley Tisdale from High School Musical.

In 2012, CMT produced a reality style series called Cheer that followed a senior team from the club gym, Central Jersey Allstars, on their road to the Cheerleading Worlds.

Beginning in 2013, the YouTube channel AwesomenessTV created a series streamed on the platform that followed the well known and well decorated senior coed team “Smoed” from the California Allstars program in San Marcos, California. The show has since gone on for eight seasons and documents the team’s yearly quest to win at the Cheerleading Worlds.

Cheer Squad is a Canadian reality television series that debuted on ABC Spark on July 6, 2016 and in the US on Freeform on August 22, 2016. It follows the Canadian club cheer team the Great White Sharks as they work together on the road to the Cheerleading Worlds. As of 2018 there is only one season, with no clear plans to renew the show.

In January 2020, Netflix released Cheer, a six-part docu-series following the Navarro College co-ed cheerleading team on their journey to NCA College Nationals in Daytona Beach, Florida.

- Video games

Nintendo has released a pair of video games in Japan for the Nintendo DS, Osu! Tatakae! Ouendan and its sequel Moero! Nekketsu Rhythm Damashii that star teams of male cheer squads, or Ouendan that practice a form of cheerleading. Each of the games' most difficult modes replaces the male characters with female cheer squads that dress in western cheerleading uniforms. The games task the cheer squads with assisting people in desperate need of help by cheering them on and giving them the motivation to succeed. There are also an All Star Cheerleader and We Cheer for the Wii in which one does routines at competitions with the Wiimote & Nunchuck. All Star Cheerleader is also available for Nintendo DS.

Cheerleading in Canada

Cheerleading in Canada is rising in popularity among the youth in co-curricular programs. Cheerleading has grown from the sidelines to a competitive activity throughout the world and in particular Canada. Cheerleading has a few streams in Canadian sports culture. It is available at the middle-school, high-school, collegiate, and best known for all-star. There are multiple regional, provincial, and national championship opportunities for all athletes participating in cheerleading. Canada does not have provincial teams, just a national program referred to as CCU or Team Canada. Their first year as a national team was in 2009 when they represented Canada at the International Cheer Union World Cheerleading Championships International Cheer Union (ICU).[96]

Competition in Canada

There is no official governing body for Canadian cheerleading. The rules and guidelines for cheerleading used in Canada are the ones set out by the USASF. However, there are many organizations in Canada that put on competitions and have separate and individual rules and scoresheets for each competition. Cheer Evolution is the largest cheerleading and dance organization for Canada. They hold many competitions as well as provide a competition for bids to Worlds. There are other organizations such as the Ontario Cheerleading Federation (Ontario), Power Cheerleading Association (Ontario), Kicks Athletics (Quebec), and the International Cheer Alliance (Vancouver). There are over forty recognized competitive gym clubs with numerous teams that compete at competitions across Canada.[97]

Canadian Cheer of the Global Stage

There are two world championship competitions that Canada participates in. The first is the ICU World Championships where the Canadian National Teams compete against other countries. The second is The Cheerleading Worlds where Canadian club teams, referred to as "all-star" teams, compete at the USASF Cheerleading Worlds. National team members who compete at the ICU Worlds can also compete with their "all-star club" teams.[98] Although athletes can compete in both International Cheer Union (ICU) and USASF, crossovers between teams at each individual competition are not permitted. Teams compete against the other teams from their countries on the first day of competition and the top three teams from each country in each division continue to finals. At the end of finals, the top team scoring the highest for their country earns the "Nations Cup". Canada has multiple teams across their country that compete in the USASF Cheerleading Worlds Championship.[99]

The International Cheer Union (ICU) is built of 103 countries that compete against each other in four divisions; Coed Premier, All-girl Premier, Coed Elite, and All-girl Elite. Canada has a national team ran by the Canadian Cheer Union (CCU). Their Coed Elite Level 5 Team and their All-girl Elite Level 5 team are 4-time world champions. The athletes on the teams are found from all over the country. In 2013, they added two more teams to their roster. A new division that will compete head-to-head with the United States: in both the All-girl and Coed Premier Level 6 divisions. Members tryout and are selected on the basis of their skills and potential to succeed. Canada's national program has grown to be one of the most successful programs.[100]

Cheerleading in the United Kingdom

Cheerleading in Australia

Notable former cheerleaders

See also

- Cheerleader Nation

- Cheerleading in Japan

- Cheerleading Philippines

- Color guard

- Dance squad

- Dance

- Gymnastics

- List of cheerleading jumps

- List of cheerleading stunts

- Majorette (dancer)

- National Basketball Association Cheerleading

- National Football League Cheerleading

- Pep squad

- Pom-pom

- UAAP Cheerdance Competition

- Varsity Brands

References

- "Cheerleading: number of participants U.S. 2017". Statista. Retrieved 2020-09-15.

- http://cheerunion.org/about/about/

- Campo-Flores, Arian (2007-05-14). "A World of Cheer!". Newsweek. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

- Golden, Suzi J. Best Cheers: How to Be the Best Cheerleader Ever! WA: Becker & Mayer, 2004, p. 5.

- Hanson, Mary Ellen. Go! Fight! Win!: Cheerleading in American Culture. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State Univ. Popular, 1995, p. 9.

- Unknown Author. "History of Cheerleading". Lee's Summit High School student projects. Archived from the original on 2007-02-18. Retrieved 2007-02-18.

- http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?wid=5&hid=138&sid=76593of7-86e8-413b-8483-6f6cf5647f11@sessionmgr110&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGIZZQ==#db=f6h%25NV=47640654%5B%5D

- "First Intercollegiate Football Game; Princeton.edu". princeton.edu. Retrieved 2014-12-16.

- https://cheerunion.org.ismmedia.com/ISM3/std-content/repos/Top/docs/ICU_History_2018.pdf

- The Daily Princetonian. 1(13): 4. February 22, 1877.

- The Daily Princetonian. 4(16): 1. March 12, 1880.

- The Daily Princetonian. 6(8): 5 November 4, 1881.

- "Princeton University website Songs and Cheers". Princeton.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-11-02. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- "Thomas Peebles". History of Minneapolis, Gateway to the Northwest Chicago-Minneapolis: The S J Clarke Publishing Co. 1923. Marion Daniel Shutter, ed. Volume III: Biographical, pp. 719–720.

- "International Cheer Union, Governing Body of International Cheerleading Website: History of Cheerleading". Cheerunion.org. 1989-01-01. Archived from the original on 2012-07-23. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- The Daily Princetonian. 22(78): 2. October 26, 1897.

- The Daily Princetonian. 25(112): 2. November 1, 1900.

- Neil, Randy L.; Hart, Elaine (1986). The Official Cheerleader's Handbook (Revised Fireside Edition 1986 ed.). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-61210-8.

- Walker, Marisa (February 2005). "Cheer Milestones". American Cheerleader. 11 (1): 41–43.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-07-18. Retrieved 2014-11-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Hanson, Mary Ellen. Go! Fight! Win!: Cheerleading in American Culture. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State Univ. Popular, 1995, pp. 17–18.

- Golden, Suzi J. Best Cheers: How to Be the Best Cheerleader Ever! WA: Becker & Mayer, 2004, p. 5.

- Peters, Craig. Chants, Cheers, and Jumps. Philadelphia: Mason Crest, 2003, p. 16.

- Hanson, Mary Ellen. Go! Fight! Win!: Cheerleading in American Culture. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State Univ. Popular, 1995, p. 25.

- Hanson, Mary Ellen. Go! Fight! Win!: Cheerleading in American Culture. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State Univ. Popular, 1995, p. 3.

- "Being a Cheerleader - History of Cheerleading". Varsity.com. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- Hanson, Mary Ellen. Go! Fight! Win!: Cheerleading in American Culture. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State Univ. Popular, 1995, p. 20.

- Hanson, Mary Ellen. Go! Fight! Win!: Cheerleading in American Culture. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State Univ. Popular, 1995, p. 26.

- Balthaser, Joel D. (2005-01-06). "Cheerleading – Oh How far it has come!". Pop Warner. Archived from the original on November 13, 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-11.

- https://cheerunion.org.ismmedia.com/ISM3/std-content/repos/Top/docs/ICU_History_2018.pdf

- "Cheerleading Jump Herkie". Retrieved 2007-08-06.

- Peters, Craig. Chants, Cheers, and Jumps. Philadelphia: Mason Crest, 2003, p. 18.

- Hanson, Mary Ellen. Go! Fight! Win!: Cheerleading in American Culture. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State Univ. Popular, 1995, p. 55.

- "Cheerleading - sports". Britannica.com. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- "About the AACCA". Archived from the original on 2006-12-06. Retrieved 2007-01-11.

- "Being a Cheerleader – Fundraising". Varsity.com. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- Christine Farina and Courtney A. Clark, Complete Guide to Cheerleading: All the Tips, Tricks, and Inspiration (Beverly MA: Voyageur, 2011), 12. ISBN 9781610602105

- NFHS.org Archived June 8, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Universal Cheerleaders Association (UCA) 2008. 7 December 2008. Varsity.com

- "Cheerleading". Livebinders.com. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- Smith, Jennifer Renèe (February 2007). "The All-Star Chronicles". American Cheerleader. 13 (1): 40–42.

- "The Cheerleading Worlds Administered by the USASF". Varsity Brands, Inc. Archived from the original on 2009-02-03. Retrieved 2007-09-20.

- "Cheer teams to provide crowd support only at winter olympics". usacheer.org. 2018-01-23.

- "Blogspot.com". Nflcheerleader.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- International Cheer Union (ICU) Retrieved 2013-03-18.

- "USA Cheer Announces U.S. JUNIOR NATIONAL Team" (Press release). USA Cheer News. January 30, 2017. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved 2017-02-06.

- "International Federation of Cheerleading - International Federation of Cheerleading". Ifc-hdqrs.org. Archived from the original on 2012-10-23. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- https://www.usacheer.org/about

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2020-02-02. Retrieved 2020-02-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Cheerleading Association of Thailand (CAT)". Thaicheerleading.com. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- "Foundation of Japan Cheerleading Association (FJCA)". Fjca.jp. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- "International Federation of Cheerleading (IFC)". Ifc-hdqrs.org. 2012-04-20. Archived from the original on 2012-09-04. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- "Cheerleading World Championships 2011 (CWC)". Daretocheer.com. Archived from the original on 2012-02-15. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- "International Cheer Union (ICU)". cheerunion.org. 2013-03-18. Retrieved 2013-03-18.

- "Indonesian Cheerleading Community | Komunitas Cheerleading Indonesia (ICC)". Indonesiancheerleading.com. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- "Indonesia to Host 3rd Annual National Cheerleading Championships". Ifc-hdqrs.org. Archived from the original on 2012-10-23. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- "PanamericanCheer". Panamericancheer.com. Archived from the original on 19 November 2017. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- "Usasf.Net". Usasf.Net. Retrieved 2014-01-22.

- "Usasf.Net". Iasfworlds.org. Retrieved 2014-01-22.

- "The Official Site - Varsity.com - We Are Cheerleading". Varsity.com. Retrieved 2014-01-22.

- https://www.myvarsity.com/CompetitionSearch?teamType=All%20Star%2CSchool%2CRecreation

- "Cheerleading Competition, InterNationals, Westerville, Ohio". AmeriCheer. Retrieved 2014-01-22.

- "The JAM Brands Cheer and Dance Competitions, Conferences and Apparel". Thejambrands.com. Archived from the original on 2012-06-29. Retrieved 2014-01-22.

- "Universal Cheerleaders Association - Where America Cheers – HomeCollege Nationals". Uca.varsity.com. Archived from the original on 2012-07-28. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-11-26. Retrieved 2014-11-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Glatt, Ephraim (Spring 2012). "Defining Sport under Title IX: Cheerleading". Sports Lawyers Journal. 19 (1): 297–324.

- "The road to recognition". BCA resources. August 2, 2008. Archived from the original on February 26, 2008. Retrieved August 2, 2008.

- "Cheerleading in the USA: A sport and an industry". USA Today. April 26, 2002. Retrieved December 1, 2008.

- "Sport, not a sport: consider Dan the expert". The Stanford Daily. September 29, 2004. Archived from the original on January 4, 2007. Retrieved December 15, 2007.

- Meades, Jamie (September 29, 2004). "No, Cheerleading is not a Sport". SFU Cheer Resources. Simon Fraser University. Retrieved December 15, 2007.

- Adams, Tyler (May 4, 2009). "Point: What Makes a Sport a Sport?". The Quindecim. Goucher College. Archived from the original on February 24, 2010. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- "Wisconsin Court: Cheerleading a Contact Sport, Participants Can't Be Sued for Accidental Injury", Fox News, Associated Press, January 27, 2009, archived from the original on 2009-03-26, retrieved June 14, 2010

- Ziegler, Michele, "Wisconsin Supreme Court Ruling", AACCA, archived from the original on 2009-03-30, retrieved June 14, 2010

- "U.S. judge in Conn.: Cheerleading not a sport". July 21, 2010.

- Grindstaff, Laura; West, Emily (November 2006). "Cheerleading and the Gendered Politics of Sport". Social Problems. 53 (4): 500–518. doi:10.1525/sp.2006.53.4.500. JSTOR 10.1525/sp.2006.53.4.500.

- "Cheerleading should be designated a sport, say medical officials". Fox News. June 10, 2014.

- Labella, C. R.; Mjaanes, J.; Council on Sports Medicine Fitness (2012), "American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Policy statement. Cheerleading injuries: epidemiology and recommendations for prevention.", Pediatrics, 130 (5): 966–971, doi:10.1542/peds.2012-2480, PMID 23090348

- "Injured Cheerleader Defends Dangerous Stunts". ABC News. 8 March 2006. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- "Cheer Bans continue". Athletic Management (August/September 2006). Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- "Cheerleader worried for team, not herself". Archived from the original on 2006-04-21. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- "Cheerleading programs going all-out for safety". Archived from the original on April 14, 2008. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- "Newton North grad dies in cheerleading accident". Boston.com. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- "Catastrophic Sport Injury Research 28th Annual Report 2011" (PDF). National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injury Research. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- "Evidence Soup". Evidence Soup. 2009-06-22. Archived from the original on 2012-03-28. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- "Cheerleading Dangers". Connectwithkids.com. Archived from the original on 2008-11-20. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- "Dangers Of Cheerleading". CBS News. April 22, 2004. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- Boden, Barry P; Tacchetti, Robin; Mueller, Frederick O (November 1, 2003). "Catastrophic Cheerleading Injuries". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 31 (6): 881–888. doi:10.1177/03635465030310062501. PMID 14623653. S2CID 34310970.

- "Health Warnings for Cheerleading". Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- "High risks for girls who high kick". Irish Examiner. 2009-06-30. p. 9.

- "Girls' Most Dangerous Sport: Cheerleading". LiveScience.com. August 11, 2008. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- Spring LaFevre. "AACCA.org". AACCA.org. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- "Pediatric Injury Prevention, Education and Research Program". Colorado School of Public Health. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- R. Dawn Comstock, Christy L. Collins, Dustin Currie (2013). "Convenience Sample Summary Report : National High Scholl Sports-related Injury Study : 2012-2013 School Year" (PDF). pp. 181–187. Retrieved October 14, 2013.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Farina, Christine. (2011). The complete guide to cheerleading : all the tips, tricks, and inspiration. Clark, Courtney A., 1960-. Minneapolis, MN: MVP Books. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7603-3849-0. OCLC 662404927.

- "'Heroes' Reborn: All You Need To Know About Season 2". Access Hollywood. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- "CCU "About"". Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- "Find A Club Near You". Cheer Evolution. Archived from the original on 3 May 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- "Canada looks for fourth straight gold medal". 19 April 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- "United States All Star Federation". USASF. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- "teamcanadacheer". Teamcanadacheer. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cheerleading. |

| Look up cheerleading in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |