Chillon Castle

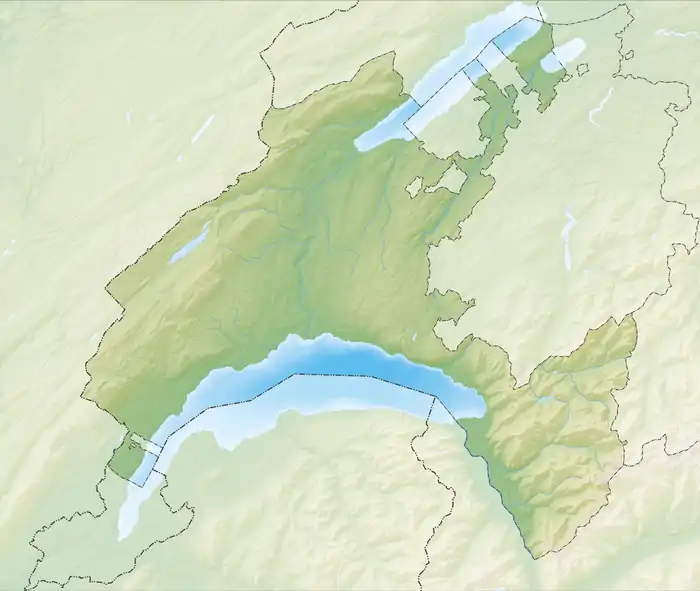

Chillon Castle (French: Château de Chillon) is an island castle located on Lake Geneva (Lac Léman), south of Veytaux in the canton of Vaud. It is situated at the eastern end of the lake, on the narrow shore between Montreux and Villeneuve, which gives access to the Alpine valley of the Rhône. Chillon is amongst the most visited castles in Switzerland and Europe.[1] Successively occupied by the house of Savoy then by the Bernese from 1536 until 1798, it now belongs to the State of Vaud and is classified as a Swiss Cultural Property of National Significance.[2] The Fort de Chillon, its modern counterpart, is hidden in the steep side of the mountain.

| Château de Chillon | |

|---|---|

View from the north, with the Dents du Midi in the background | |

Location in Vaud  Location in Switzerland | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Medieval |

| Classification | Historic monument |

| Town or city | Veytaux, Vaud |

| Country | Switzerland |

| Coordinates |  46°24′51″N 6°55′39″E

46°24′51″N 6°55′39″E |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Jacques de Saint-Georges |

History

Chillon began as a Roman outpost, guarding the strategic road through the Alpine passes.[3] The later history of Chillon was influenced by three major periods: the Savoy Period, the Bernese Period, and the Vaudois Period.[4]

The castle of Chillon is built on the island of Chillon,[5] an oval limestone rock advancing in Lake Geneva between Montreux and Villeneuve with a steep side on one side and on the other side the lake and its steep bottom. The placement of the castle is strategic: it closes the passage between the Vaud Riviera (access to the north towards Germany and France) and the Rhone valley which allows quick access to Italy. Moreover, the place offers an excellent point of view on the Savoyard coast facing. A garrison could thus control (both militarily and commercially) access to the road to Italy and apply a toll. According to the Swiss ethnologist Albert Samuel Gatschet, the name Chillon comes from Waldensian dialect and would mean "flat stone, slab, platform". Castrum Quilonis (1195) would therefore mean "castle built on a chillon," that is to say on a rock platform.[6]

The first construction dates back to around the 10th century, although it is likely that it was already a privileged military site before that date. Objects dating back to Roman times were discovered during excavations in the 19th century, as well as remains from the Bronze Age. From a double wooden palisade, the Romans would have fortified the site before a square dungeon was added in the 10th century. Sources from the 13th century link the possession of the Chillon site to the Bishop of Sion.

A charter of 1150, where Count Humbert III grants the Cistercians of Hautcrêt free passage to Chillon, attests to the domination of the House of Savoy on Chillon. The owner of the castle is mentioned as Gaucher de Blonay, a vassal of the Count of Savoy. At the time it was a seigniorial domination of the Savoy within the framework of a feudal society and not an administrative domination.

Savoy period

The oldest parts of the castle have not been definitively dated, but the first written record of the castle was in 1005.[7] It was built to control the road from Burgundy to the Great Saint Bernard Pass.[8] From the mid 12th century, the castle was summer home to the Counts of Savoy, who kept a fleet of ships on Lake Geneva. The castle was greatly expanded in 1248[8] and 1266-7 by Peter II.[9] During this time the distinctive windows were added that would later be added to Harlech Castle by Master James of Saint George.[10]

Chillon as a prison

During the 16th century Wars of Religion, it was used by the dukes of Savoy to house prisoners. Its most famous prisoner was probably François de Bonivard, a Genevois monk, prior of St. Victor in Geneva and politician who was imprisoned there in 1530 for defending his homeland from the dukes of Savoy.[8] Over his six-year term, de Bonivard paced as far as his chain would allow, and the chain and rut are still visible.

Bernese period

In 1536 the castle was captured by a Genevois and Bernese force. All the prisoners, including de Bonivard, were released. The castle became the residence for the Bernese bailiff until Chillon was converted into a state prison in 1733.[8]

Vaudois period

In 1798, the French-speaking canton of Vaud drove out the German-speaking Bernese authorities and declared the Lemanic Republic. The Vaudois invited in French troops to help them maintain autonomy from the other Swiss. When the French moved in and occupied, Chillon was used as a munitions and weapons depot.[8]

Restoration

At the end of the 19th century, structures were set up for a scientific restoration of the monument. This systematic undertaking, a true laboratory where an ethic of monumental restoration is developed, was considered quite exemplary. It was boasted in particular by Johann Rudolf Rahn in a lecture given in 1898 to the Zurich Antiquity Society,[11] and the German Emperor himself, William II, inquired about the Chillon model in view of the reconstruction of the fortress of Haut-Koenigsbourg.[12]

This result is due to the conjunction of several factors:

- the emergence of particularly competent personalities;

- the creation of the Association for the restoration of Chillon;

- the appointment of a Technical Commission to guide the work;

- the adoption by the Canton of Vaud of the 1898 law on historic monuments.

The reconstruction of Chillon was one of the first times that the sciences of archaeology and history were applied to rebuild a structure in an historically accurate way.

The intervention of pioneering personalities in the protection of monuments is decisive. In particular: Johann Rudolf Rahn, one of the main protagonists at the origin of the Swiss Society of Historical Monuments in 1880, and Henry de Geymüller, international specialist of the monumental restoration, closely associated with the rehabilitation of buildings such as the Romanesque church of Church of Saint-Sulpice, Vaud in Saint-Sulpice, the Saint-François church in Lausanne, and the Lausanne Cathedral. In addition, Ernest Burnat, who was also very involved in Lausanne Cathedral, was initially named architect of this restoration and was replaced by Albert Naef, who played a major role in the development of archaeology in the canton of Vaud and devoted twenty years of his life to the study of Chillon.[13]

The Association for the restoration of the castle of Chillon was constituted in 1887.[14] From the outset, it aimed for an "artistic" restoration with the intention of "giving back to objects the character with which they were clothed, almost a latent life, a life impression of the ideas of their time".[15] It is also planned to create a historical museum at the castle.[16]

A technical commission, ratified in 1889, was composed of renowned art historians and architects, specialized in the monumental restoration: Johann Rudolf Rahn, Théodore Fivel, architect in Chambéry and great connoisseur of Savoyard castrale architecture, Léo Chatelain, restorer of the Collegiate Church of Neuchâtel, Henry de Geymüller, theoretician of the restoration and specialist of the Renaissance architecture, finally Henri Assinare, architect of the State. Their first meeting took place on October 27, 1890 and from then on these specialists, for many years, closely supervised the work. Geymüller, in particular, relying on principles already published in 1865 (and augmented in 1888) by the Royal Institute of British Architects,[17] set a framework by writing a memoir entitled Milestones for the Restoration Program and Fundamental Principles on which it was to be based (printed in Lausanne in 1896).[13]

The Waldensian law of 1898 – the first of its kind in Switzerland – was drafted by Albert Naef. In particular, it planned to establish a cantonal commission for historic monuments and to create a cantonal archeologist's post. Naef, of course, was appointed to this function and was responsible for putting in place a real protection of historical monuments.[18]

The systematic investigation of the castle was begun by Ernest Burnat, who initiated a general survey of the fortress, then continued and intensified by Albert Naef. The latter not only joined the Technical Commission at the death of Fivel in 1895, but replaced Burnat himself as architect-archaeologist in charge of the work. In his approach, aesthetics always remained subordinate to scientific ethics. The restoration had to be based on as much knowledge of the monument as possible and the investigation was methodical. It took into account the achievements of history through extensive research in the archives, it carried out archaeological excavations and detailed records, if necessary even to casts. The castle was literally laid bare, the whole process being conscientiously documented by plans, sketches and photographs, as well as by a minute newspaper that Naef kept from day to day. During the restoration, the replacement stones were duly indicated as such, by an inscription on the cut stone (R = Restored, RFS = Restoration facsimile, RL = Free Restoration), or by a change of color, or even a red line, on the masonry. This rule was truly respected until 1908, then was forgotten.[13]

Tourism

Since the end of the 18th century, the castle has attracted romantic writers. From Jean-Jacques Rousseau to Victor Hugo via Alexandre Dumas, Gustave Flaubert and Lord Byron, the castle has inspired poets from around the world. Hugo says "Chillon is a block of towers on a block of rocks." Some restorations, inspired by the romantic vision of aesthetics, were at the expense of historical veracity. In 1900, the architect Albert Naef continued the restoration work to reach the current state of the building. He remade the interior and the tapestries of certain rooms such as the great room of the bailiff, also called the "great Bernese cuisine."

By 1939, the castle was hosting over 100,000 visitors a year. The proximity to the popular city of Montreux has not been unrelated to this craze. Success continues to grow over the years and by 2005 the monument now had about 300,000 visits per year.[19] Thanks to the restorations, the castle is in excellent condition and gives a good model of the feudal architecture.

The castle has twice hosted the Compagnie du Graal theater company based in Thonon-les-Bains, to play a sound and light adaptation of King Lear by Shakespeare in 2009 and in 2012 an epic fresco inspired by Ancient Greece : Hyperion.

Art

A mechanical automaton representing the Chillon Castle, 100 cm × 67 cm × 42 cm (39 in × 26 in × 17 in), 1/100 scale, made of zinc, steel and brass, equipped with a music box with the handwritten original sheet music by the Genevan composer E. Perrin, illustrates the capture of the castle and the liberation of François Bonivard by the Bernese in 1536. Dating from 1890 and made during a period of five years by the watchmaker Edouard- GabrielWuthrich, the automaton maneuvers a hundred figurines, including many small soldiers. Barred windows also show the interior of the castle, including scenes of torture in prisons. After having disappeared for decades and being found in various homes, the automaton was eventually acquired by the Association of Friends of Chillon, the Cantonal Museum of Archeology and History (MCAH) and the Castle Foundation, for 59,000 Swiss francs, at an auction held in Paris in March 2016.[20][21][22]

Having been inspired by the story of François Bonivard after a visit to the castle, Lord Byron wrote a poem on The Prisoner of Chillon in 1816.

Gustave Courbet painted the castle several times during his Swiss exile not far from there, in La Tour-de-Peilz. The most famous representation is "The Castle of Chillon," oil on canvas painted in 1874 and currently located at the Musée Courbet in Ornans.[23] The painter E. Lapierre (19th-20th century) also made an oil painting of the castle on canvas in 1896.

In his novel "Daisy Miller" of 1878, Henry James stages Chillon Castle as a place of visit for his heroine and his young American compatriot Winterbourne. What was the prison of François Bonivard thus takes, from the beginning of the news, a symbolic and premonitory meaning of the destiny of Daisy Miller who thinks he can escape the shackles of social conventions.

Today

Chillon is open to the public for visits and tours. According to the castle website, Chillon is listed as "Switzerland's most visited historic monument".[24] There is a fee for entrance and there are both parking spaces and a bus stop nearby for travel. Inside the castle there are several recreations of the interiors of some of the main rooms including the grand bedroom, hall, and cave stores. Inside the castle itself there are four great halls, three courtyards, and a series of bedrooms open to the public. One of the oldest is the Camera domini, which was a room occupied by the Duke of Savoy – it is decorated with 14th century medieval murals.[25]

Popular culture

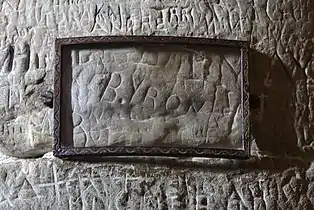

- Chillon is the setting of Lord Byron's poem The Prisoner Of Chillon (1816) about François de Bonivard. Byron also carved his name on a pillar of the dungeon.

- The castle is one of the settings in Henry James's novella Daisy Miller (1878).

- Chillon inspired the castle in the Disney animated film The Little Mermaid.[26]

- The castle was used as the cover image of Bill Evans' 1968 live album Bill Evans at the Montreux Jazz Festival.

Gallery

Chillon Castle at nightfall with the Dents du Midi in the background

Chillon Castle at nightfall with the Dents du Midi in the background Chillon Castle and Motorway

Chillon Castle and Motorway From the south

From the south From above

From above Front

Front Chillon Castle crypt

Chillon Castle crypt Grand Hall of the Count

Grand Hall of the Count The castle courtyard

The castle courtyard Byron's signature in the dungeon

Byron's signature in the dungeon Chateau du Chillon by Gustave Courbet, 1875

Chateau du Chillon by Gustave Courbet, 1875 Chillon Castle, aerial view

Chillon Castle, aerial view

See also

- Fort de Chillon – a 20th-century fort largely buried in the adjoining hillside

- List of castles in Switzerland

Notes

- Mc Currach, Ian (27 April 2003). "One Hour From: Geneva". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2014-07-30.

- "Swiss inventory of cultural property of national and regional significance". A-Objects. Federal Office for Cultural Protection (BABS). 1 January 2018. Archived from the original on 2 September 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- de Fabianis, p. 176.

- "Château de Chillon - History overview". Chillon.ch. Archived from the original on 2009-07-13. Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- Gil, Annika (December 13, 2006). "Combien d'îles sur le lac Léman" (PDF). La Gazette.

- Jaccard, Henri (1867). Essai de Toponymie. La Société d'Histoire de la Suisse Romande. ISBN 978-1-141-93817-9.

- According to publication Chillon by Auguste Guignard (former secretary of the Association for the Restoration of the Chillon Castle), published by Ruckstuhl SA (Renens, Switzerland) in 1996: "The oldest historical document relating to Chillon bears the date 1005, and from this it is seen that the castle belonged to the bishops of Sion, who confided its care to the d'Alinge family."

- de Fabianis, p. 175.

- Cox 1967, p. 20.

- Taylor, Arnold (1985). Studies in Castles and Castle-Building. London. The Hambledon Press.

- Bissegger, Paul (2010). "Henri de Geymüller versus E.-E. Viollet-le-Duc: le monument historique comme document et œuvre d'art. Avec un choix de textes relatifs à la conservation patrimoniale dans le canton de Vaud vers 1900". Monuments Vaudois. Association Edimento: 5–40.

- Bertholet, Denis; Feihl, Olivier; Huguenin, Claire (1998). Autour de Chillon: Archéologie et Restauration au Début du Siècle. Lausanne: Musée Cantonal d'Archéologie et d'Histoire. p. 182.

- Bertholet, Denis; Feihl, Olivier; Huguenin, Claire (1998). Autour de Chillon: Archéologie et Restauration au Début du Siècle. Lausanne: Musée Cantonal d'Archéologie et d'Histoire.

- "N 2 Château de Chillon, 0600-2003 (Fonds)". www.davel.vd.ch. Retrieved 2019-05-17.

- Lettre Circulaire, 1887. Lausanne: Archives Cantonales Vaudoises. 1887. p. 131.

- Huguenin, Claire (2010). Patrimoines en Stock: Les Collections de Chillon. Lausanne: Musée Cantonal d'Archéologie et d'Histoire.

- Conservation of Ancient Monuments and Remains. General Advice to Promoters of Restoration of Ancient Buildings. London: Sessional Papers of the Royal Institute of British Architects 1864-1865. 1865. p. 29.

- Bertholet, Denis (1998). La Loi de 1898. Lausanne: Musée Cantonal d'Archéologie et d'Histoire. pp. 41–48.

- Chillon in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Béda, Claude (2016-06-21). "Disparu durant un siècle, un automate fait revivre l'illustre prisonnier de Chillon". VQH (in French). ISSN 1424-4039. Retrieved 2019-05-16.

- "Couleurs locales - Vidéo". Play RTS (in French). Retrieved 2019-05-16.

- "VD: l'automate d'exception du château de Chillon se remet en marche - Vidéo". Play RTS (in French). Retrieved 2019-05-17.

- "Le château de Chillon (1874)". musee-courbet.com. Archived from the original on 2007-10-16. Retrieved 2019-05-28.

- "Chillon Website - Main Page". Chillon.ch. Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- "Chillon Website - Rooms". Chillon.ch. Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- Morton, Caitlin (14 June 2017). "17 Real-World Locations That Inspired Disney Movies". Condé Nast Traveler. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

References

- Cox, Eugene L. (1967). The Green Count of Savoy. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. LCCN 67-11030.

- de Fabianis, Valeria, ed. (2013). Castles of the World. New York: Metro Books.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) ISBN 978-1-4351-4845-1

- Fonds : Château de Chillon (600-2013) [Archives de l'Association du château de Chillon (antérieurement Association pour la restauration du château de Chillon) et archives provenant du Secrétariat général du Département de l'instruction publique et des cultes et du Service des bâtiments concernant le château de Chillon : photographies, plans, inventaires, journaux de fouilles, écrits non publiés, contrats, règlements, procès-verbaux, rapports, correspondance, comptabilité, imprimés, publicité, registres des visiteurs du château, dossiers divers, archives de l'architecte Otto Schmid. 172,20 mètres linéaires]. Cote : CH-000053-1 N 2. Archives cantonales vaudoises. (présentation en ligne [archive])

- Denis Bertholet, Olivier Feihl, Claire Huguenin, Autour de Chillon. Archéologie et restauration au début du siècle, Lausanne 1998.

- Claire Huguenin, Patrimoines en stock. Les collections de Chillon, Lausanne 2010.

- Paul Bissegger, «Henri de Geymüller versus E.-E. Viollet-le-Duc: le monument historique comme document et œuvre d'art. Avec un choix de textes relatifs à la conservation patrimoniale dans le canton de Vaud vers 1900», Monuments vaudois 2010, p. 5-40.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Château de Chillon. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |