Rhône

The Rhône (/roʊn/ ROHN, French: [ʁon] (![]() listen); German: Rhone [ˈroːnə] (

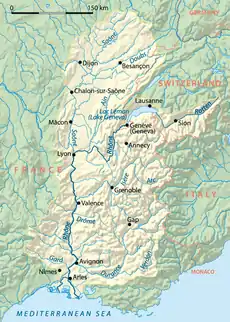

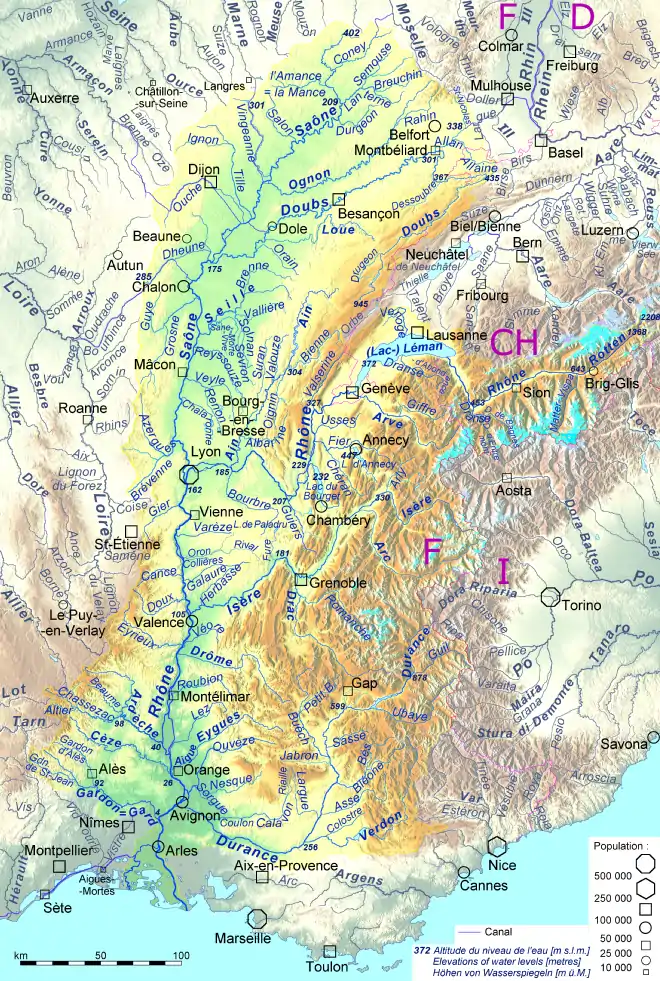

listen); German: Rhone [ˈroːnə] (![]() listen); Walser: Rotten [ˈrotən]; Italian: Rodano [ˈrɔːdano]; Francoprovençal: Rôno [ˈʁono]; Occitan: Ròse [ˈrɔze, ˈʀɔze]) is one of the major rivers of Europe and has twice the average discharge of the Loire (which is the longest French river), rising in the Rhône Glacier in the Swiss Alps at the far eastern end of the Swiss canton of Valais, passing through Lake Geneva and running through southeastern France. At Arles, near its mouth on the Mediterranean Sea, the river divides into two branches, known as the Great Rhône (French: le Grand Rhône) and the Little Rhône (le Petit Rhône). The resulting delta constitutes the Camargue region.

listen); Walser: Rotten [ˈrotən]; Italian: Rodano [ˈrɔːdano]; Francoprovençal: Rôno [ˈʁono]; Occitan: Ròse [ˈrɔze, ˈʀɔze]) is one of the major rivers of Europe and has twice the average discharge of the Loire (which is the longest French river), rising in the Rhône Glacier in the Swiss Alps at the far eastern end of the Swiss canton of Valais, passing through Lake Geneva and running through southeastern France. At Arles, near its mouth on the Mediterranean Sea, the river divides into two branches, known as the Great Rhône (French: le Grand Rhône) and the Little Rhône (le Petit Rhône). The resulting delta constitutes the Camargue region.

| Rhône Rhone | |

|---|---|

View over the Rhône flowing from Valais into Lake Geneva | |

| |

| Native name | Rotten (Walser) Rôno (Arpitan) Ròse (Occitan) |

| Location | |

| Countries | Switzerland and France |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Rhône Glacier |

| • location | Valais, Switzerland |

| • elevation | 2,208 m (7,244 ft) |

| Mouth | Mediterranean Sea |

• location | France |

• coordinates | 43°19′51″N 4°50′44″E |

• elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Length | 813 km (505 mi) |

| Basin size | 98,000 km2 (38,000 sq mi) |

| Discharge | |

| • average | 1,710 m3/s (60,000 cu ft/s) |

| • minimum | 360 m3/s (13,000 cu ft/s) |

| • maximum | 13,000 m3/s (460,000 cu ft/s) |

The Rhône is one of the four major rivers taking their source in the Gotthard region, along with the Reuss, Rhine and Ticino.

Etymology

The name Rhone continues the name Latin: Rhodanus (Greek Ῥοδανός Rhodanós) in Greco-Roman geography. The Gaulish name of the river was *Rodonos or *Rotonos (from a PIE root *ret- "to run, roll" frequently found in river names).

The Greco-Roman as well as the reconstructed Gaulish name is masculine, as is French le Rhône. This form survives in the Spanish/Portuguese and Italian namesakes, el/o Ródano and il Rodano, respectively. German has adopted the French name but given it the feminine gender, die Rhone. The original German adoption of the Latin name was also masculine, der Rotten; it survives only in the Upper Valais (dialectal Rottu).

In French, the adjective derived from the river is rhodanien, as in le sillon rhodanien (literally "the furrow of the Rhône"), which is the name of the long, straight Saône and Rhône river valleys, a deep cleft running due south to the Mediterranean and separating the Alps from the Massif Central.

Navigation

Before railroads and highways were developed, the Rhône was an important inland trade and transportation route, connecting the cities of Arles, Avignon, Valence, Vienne and Lyon to the Mediterranean ports of Fos-sur-Mer, Marseille and Sète. Travelling down the Rhône by barge would take three weeks. By motorized vessel, the trip now takes only three days. The Rhône is classified as a Class V waterway for the 325 km long section from the mouth of the Saône at Lyon to the sea at Port-Saint-Louis-du-Rhône.[1] Upstream from Lyon, a 149 km section of the Rhône was made navigable for small ships up to Seyssel. As of 2017, the part between Lyon and Sault-Brénaz is closed for navigation.[2]

The Saône, which is also canalized, connects the Rhône ports to the cities of Villefranche-sur-Saône, Mâcon and Chalon-sur-Saône. Smaller vessels (up to CEMT class I) can travel further northwest, north and northeast via the Centre-Loire-Briare and Loing Canals to the Seine, via the Canal de la Marne à la Saône (recently often called the "Canal entre Champagne et Bourgogne") to the Marne, via the Canal des Vosges (formerly called the "Canal de l'Est – Branche Sud") to the Moselle and via the Canal du Rhône au Rhin to the Rhine.

The Rhône is infamous for its strong current when the river carries large quantities of water: current speeds up to 10 kilometres per hour (6 mph) are sometimes reached, particularly in the stretch below the last lock at Vallabrègues and in the relatively narrow first diversion canal south of Lyon. The 12 locks are operated daily from 5:00 a.m. until 9:00 p.m. All operation is centrally controlled from one control centre at Châteauneuf. Commercial barges may navigate during the night hours by authorisation.[3]

Course

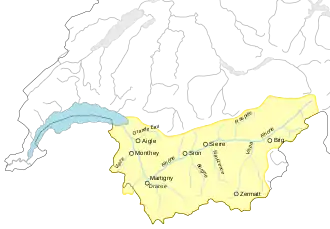

The Rhône rises as the meltwater of the Rhône Glacier in the Valais, in the Swiss Alps, at an altitude of approximately 2,208 metres (7,244 ft).[4] From there it flows southwest through Gletsch and the Goms, the uppermost valley region of the Valais before Brig. Shortly before reaching Brig, it receives the waters of the Massa from the Aletsch Glacier. It flows onward through the valley which bears its name and runs initially in a westerly direction about thirty kilometers to Leuk, then southwest about fifty kilometers to Martigny.

Down as far as Brig, the Rhône is a torrent; it then becomes a great mountain river running southwest through a glacier valley. Between Brig and Martigny, it collects waters mostly from the valleys of the Pennine Alps to the south, whose rivers originate from the large glaciers of the massifs of Monte Rosa, Dom, and Grand Combin.

At Martigny, where it receives the waters of the Drance on its left bank, the Rhône makes a strong turn towards the north. Heading toward Lake Geneva, the valley narrows near Saint-Maurice, a feature that has long given the Rhône valley strategic importance for the control of the Alpine passes. The Rhône then marks the boundary between the cantons of Valais (left bank) and Vaud (right bank), separating the Valais Chablais and Chablais Vaudois. It enters Lake Geneva near Le Bouveret.

On a portion of its extent Lake Geneva marks the border between France and Switzerland. On the left bank of Lake Geneva the river receives the river Morge. This river marks the border between France (Haute-Savoie) and Switzerland (Valais). The Morge enters Lake Geneva at Saint-Gingolph, a village with two parts (a Swiss and a French one) on both sides of the border. Then between Évian-les-Bains and Thonon-les-Bains the Dranse enters the lake where it left a quite large delta. On the right bank of the lake the Rhône receives the Veveyse, the Venoge, the Aubonne and the Morges besides others.

Lake Geneva ends in Geneva, where the lake level is maintained by the Seujet dam. The average discharge from Lake Geneva is 251 cubic metres per second (8,900 cu ft/s).[5] In Geneva, the Rhône receives the waters of the Arve from the Mont Blanc. After a course of 290 kilometres (180 mi) the Rhône leaves Switzerland and enters the southern Jura Mountains. It then turns toward the south past the Bourget Lake which it is connected by the Savières channel. At Lyon, which is the biggest city along its course, the Rhône meets its biggest tributary, the Saône. The Saône carries 400 cubic metres per second (14,000 cu ft/s) and the Rhône itself 600 cubic metres per second (21,000 cu ft/s). From the confluence, the Rhône follows the southbound direction of the Saône. Along the Rhône Valley, it is joined on the right (western) bank by the rivers Eyrieux, Ardèche, Cèze, and Gardon coming from the Cévennes mountains; and on the left bank by the rivers Isère, with an average discharge of 350 cubic metres per second (12,000 cu ft/s), Drôme, Ouvèze, and Durance at 188 cubic metres per second (6,600 cu ft/s) from the Alps.

From Lyon, it flows south, in its large valley between the Alps and the Massif Central. At Arles, the Rhône divides into two major arms forming the Camargue delta, both branches flowing into the Mediterranean Sea, the delta being termed the Rhône Fan. The larger arm is called the "Grand Rhône", the smaller the "Petit Rhône". The average annual discharge at Arles is 1,710 cubic metres per second (60,000 cu ft/s).[5]

History

The Rhône has been an important highway since the times of the Greeks and Romans. It was the main trade route from the Mediterranean to east-central Gaul.[6] As such, it helped convey Greek cultural influences to the western Hallstatt and the later La Tène cultures.[6] Celtic tribes living near the Rhône included the Seduni, Sequani, Segobriges, Allobroges, Segusiavi, Helvetii, Vocontii and Volcae Arecomici.[6]

Navigation was difficult, as the river suffered from fierce currents, shallows, floods in spring and early summer when the ice was melting, and droughts in late summer. Until the 19th century, passengers travelled in coches d'eau (water coaches) drawn by men or horses, or under sail. Most travelled with a painted cross covered with religious symbols as protection against the hazards of the journey.[7]

Trade on the upper river used barques du Rhône, sailing barges, 30 by 3.5 metres (98 by 11 ft), with a 75-tonne (165,000 lb) capacity. As many as 50 to 80 horses were employed to haul trains of five to seven craft upstream. Goods would be transshipped at Arles into 23-metre (75 ft) sailing barges called allèges d'Arles for the final run down to the Mediterranean.

The first experimental steam boat was built at Lyon by Jouffroy d'Abbans in 1783. Regular services were not started until 1829 and they continued until 1952. Steam passenger vessels 80 to 100 metres (260–330 ft) long made up to 20 kilometres per hour (12 mph) and could do the downstream run from Lyon to Arles in a day. Cargo was hauled in bateau-anguilles, boats 157 by 6.35 metres (515.1 by 20.8 ft) with paddle wheels amidships, and bateaux crabes, a huge toothed "claw"wheel 6.5 metres (21 ft) across to grip the river bed in the shallows to supplement the paddle wheels. In the 20th century, powerful motor barges propelled by diesel engines were introduced, carrying 1,500 tonnes (3,300,000 lb).

In 1933, the Compagnie Nationale du Rhône (CNR) was established to improve navigation and generate electricity, also to develop irrigated agriculture and to protect the riverside towns and land from flooding. Some progress was made in deepening the navigation channel and constructing scouring walls, but World War II brought such work to a halt. In 1942, following the collapse of Vichy France, Italian military forces occupied southeastern France up to the eastern banks of the Rhône, as part of the Italian Fascist regime's expansionist agenda.

Postwar development

In 1948, the government started construction of a series of dams and diversion canals, with a navigation lock beside the hydroelectric power plant on each of these canals. The locks were up to 23 metres (75 ft) deep. After building the Génissiat dam on the Upper Rhône (with no lock) in 1948,[8][9] designed to meet the electricity needs of Paris, twelve hydroelectric plants and locks were built between 1964 and 1980. With a total head of 162 m, they produce 13 GWh of electricity annually, or 16% of the country's total hydroelectric production (20% if the Upper Rhône schemes are added). There have been significant benefits for agriculture throughout the Rhône valley.

With the Lower Rhône project completed, CNR turned its attention to the Haut-Rhône (Upper Rhône), and built four hydropower dams in the 1980s: Sault-Brénaz, Brégnier-Cordon, Belley-Brens and Chautagne. It also drew up plans for the high-capacity Rhine-Rhône Waterway, along the route of the existing Canal du Rhône au Rhin, but this project was abandoned in 1997. In the period from 2005 to 2010, navigation locks of small barge dimensions (40 by 6 m) were built to bypass the last two, forming a navigable waterway network with Lake Bourget, through the Canal de Savières.[10]

Along the Rhône

Cities and towns along the Rhône include:

Switzerland

- Oberwald (Valais)

- Brig (Valais)

- Visp (Valais)

- Leuk (Valais)

- Sierre (Valais)

- Sion (Valais)

- St. Maurice (Valais)

- see Lake Geneva for a list of Swiss and French towns around the lake

- Geneva (Geneva)

France

- Lyon, (Rhône (département))

- Vienne (Isère)

- Tournon-sur-Rhône (Ardèche) opposite Tain-l'Hermitage (Drôme)

- Valence (Drôme) opposite Saint-Péray and Guilherand-Granges (Ardèche)

- Montélimar (Drôme) opposite Le Teil and Rochemaure (Ardèche)

- Viviers (Ardèche)

- Bourg-Saint-Andéol (Ardèche)

- Pont-Saint-Esprit (Gard)

- Roquemaure (Gard) opposite Châteauneuf-du-Pape (Vaucluse)

- Avignon (Vaucluse) opposite Villeneuve-lès-Avignon (Gard)

- Beaucaire (Gard) opposite Tarascon (Bouches-du-Rhône)

- Vallabrègues (Gard)

- Arles (Bouches-du-Rhône)

See also

- Berges du Rhône

- Rhône (département)

- Rhône (wine region)

- Witenwasserenstock (triple watershed: Rhône-Rhine-Po)

References

- Fluviacarte, Rhône

- Fluviacarte, Haut Rhône

- Edwards-May, David (2010). Inland Waterways of France. St Ives, Cambs., UK: Imray. pp. 210–220. ISBN 978-1-846230-14-1.

- "255 Sustenpass" (Map). Rhône source (online map) (2015 ed.). 1:50 000. National Map 1:50 000 – 78 sheets and 25 composites (in German). Cartography by Swiss Federal Office for Topography, swisstopo. Berne, Switzerland: Swiss Federal Office for Topography, swisstopo. 2013. ISBN 978-3-302-00255-2. Retrieved 2015-10-18.

- "Le Rhône" (in French). Geneva, Switzerland: La fédération Genevoise des Sociétés de Pêche. March 2001. Retrieved 2015-10-18.

- Freeman, Philip. John T. Koch (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. I. ABC-CLIO. p. 901. ISBN 1-85109-440-7.

- McKnight, Hugh (September 2005). Cruising French Waterways (4th ed.). Sheridan House. ISBN 978-1-57409-210-3.

- Civil Engineering, Volume 43. Morgan-Grampian. 1948. p. 136.

In 1933 a state-controlled company was formed in France with the object of undertaking the planning and execution of extensive development works on the Rhône. Of these Génissiat works, the Génissiat dam and Dam power station are the most important. Started in February 1937, the construction of the dam has now been completed and on January 15th, 1948, was commenced the operation of filling the dam with water, which extended over six days.

- Far Eastern Economic Review Interactive Edition, Volume 25. Review Publishing Company Limited. 1958. p. 7.

The Génissiat dam is a powerful structure, 360 feet high and 470 feet wide, which locks the Rhône near the town of Bellegarde and stores more than two billion cubic feet of water. With this water, 5 generators of 90,000 H.P. produce 1,700 million kWh. annually. The structure, which was started in 1937 and completed in 1948, was only the first phase of a gigantic project involving the ultimate

- "Information about the 310km long river Rhône from Lyon to the Mediterranean, Summary". French Waterways. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

Further reading

- Champion, Maurice (1858–1864), Les inondations en France depuis le VIe siècle jusqu'a nos jours (6 Volumes) (in French), Paris: V. Dalmont Scans: Volume 3 (1861) (Bassin du Rhône starts at page 185), Volume 4 (1862).

- Pardé, Maurice (1925), "Le régime du Rhône", Revue de géographie alpine (in French), 13 (13–3): 459–547, doi:10.3406/rga.1925.4941.

- Pritchard, Sara B. (2011), Confluence: The Nature of Technology and the Remaking of the Rhône, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-04965-9 A social, environmental, and technological history of the transformation of the river since 1945.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rhône River. |

- InfoRhône Navigation and river conditions

- CNR The Rhône Authority

- Rhône, Petit-Rhône, and Haut-Rhône guides, with maps, detailed plans and information on places, moorings and facilities by the author of Inland Waterways of France, Imray

- Navigation details for 80 French rivers and canals (French waterways website section)

- The Rhône-Mediterranean page of EauFrance

- Waterways in France