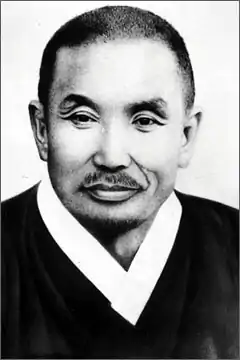

Cho Man-sik

Cho Man-sik (Korean: 조만식, pen-name Kodang) (1 February 1883 – October? 1950) was a nationalist activist in Korea's independence movement. He became involved in the power struggle that enveloped North Korea in the months following the Japanese surrender after World War II. Originally Cho was supported by the Soviet Union for the eventual rule of North Korea. However, due to his opposition to trusteeship, Cho lost Soviet support and was forced from power by the Soviet-backed communists in the north.[1] Placed under house arrest in January 1946, he later disappeared, and is generally believed to have been executed in the North Korean prison system soon after the start of the Korean War.

Cho Man-sik | |

|---|---|

조만식 | |

Cho Man-sik | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1 February 1883 Kangsŏ-gun, Joseon dynasty |

| Died | October 1950 (aged 67) Pyongyang, North Korea |

| Cause of death | Execution |

| Korean name | |

| Chosŏn'gŭl | |

| Hancha | |

| Revised Romanization | Jo Man-sik |

| McCune–Reischauer | Cho Man-sik |

| Pen name | |

| Chosŏn'gŭl | |

| Hancha | |

| Revised Romanization | Godang |

| McCune–Reischauer | Kodang |

Cho Man-sik, Gye-Jun Ryu, Kim Dong-won, Oh Yun-seon are cited as the pillars of the Sanjunghyun Church in Pyongyang.[2][3][4]

Early life

Cho was born in Kangsŏ-gun, South P'yŏngan Province, now in North Korea on 1 February 1883. He was raised and educated in a traditional Confucian style[5] but later converted to Protestantism and became an elder.[6] From June 1908 to 1913 Cho moved to Japan to study law in Tokyo at Meiji University.[7] It was during his stay in Tokyo that Cho came into contact with Gandhi’s ideas of non-violence and self-sufficiency.[8] Cho later used these ideas of non-violent opposition to resist Japanese rule.

Independence movement

After Japan's annexation of Korea in 1910 Cho became increasingly involved with his country's independence movement. His participation in the March 1st Movement led to his arrest and detention, along with tens of thousands of other Koreans. He is also famous for publicly rejecting the Japanese Imperial government's policy of pressuring Koreans to legally change their surnames into Japanese.[9] In 1922 Cho established the Korean Products Promotion Society with the objective of achieving economic self-sufficiency[10] and that Koreans could obtain solely home-produced products. Cho intended the Society to be a national movement supported by all religious organizations and social groups, particularly ordinary Koreans.[11] Due to the Korean Products Promotion Society, his strong non-violent resistance, and leading by example rather than political or social authority, Cho gained respect even from critics, and earned him the title “Gandhi of Korea”.[12] Despite this record, his encouragement of Korean student enlistment in the Japanese army earned him a mixed reputation with some of his fellow nationalists.[13]

Post World War II activism

In August 1945, with Japanese surrender imminent, Cho was approached by the Japanese governor of Pyongyang and asked to organise a committee to assume control and maintain stability in the power vacuum that would inevitably follow.[14] He agreed to co-operate, and on 17 August 1945 formed the Provisional People's Committee for the Five Provinces. The committee functioned to standardize the number of members, duties, and electoral processes for the formation of People’s Committees at the provincial, city, country, township, and village levels.[15] Cho also affiliated this committee to the Committee for the Preparation of Korean Independence (CPKI).[16] The Provisional People’s Committee for the Five Provinces generally composed of right-wing nationalists opposed to communism.[17]

When the Soviet forces arrived in Pyongyang following the Japanese surrender they hoped they could influence Cho Man-sik. Cho was at this time the most popular leader in Pyongyang due mainly to his constant resistance to the Japanese and his formation of the Korean Products Promotions Society.[18][19] Soviet officers regularly met with Cho and tried to convince him to head the emerging North Korea administration. Cho however disliked communism and did not trust foreign powers.[20] Cho Man-sik would have agreed to co-operate with the Soviet authorities only on his own terms, such as extensive autonomy. Cho's conditions were not accepted by the Soviet leaders. Despite his rejection of Soviet requests he was able to remain as chairman of the South P’yŏngan People’s Committee.[21]

On 3 November 1945, Cho also established his own political party: The Democratic Party of Korea. At the beginning it was intended to turn into an authentic political organization of the nationalist right with the aim to bring about a democratic society after Japanese occupation. The Soviets however, did not approve of the Democratic Party of Korea and thus under socialist pressure, Choi Yong-kun was elected the first deputy chairman of the party. Choi Yong-kun was a guerrilla soldier who served in the 88th brigade of the Soviet Union, and was a friend of Kim Il-sung. The party was therefore influenced by Soviet ideals from the beginning.[22]

Soviet faith that Cho Man-sik could become a North Korean leader with Soviet ideals diminished and new hope was placed on the Korean communist Kim Il-sung. Kim Il-sung had trained in the Soviet Army for ten years, rising to the rank of major. Under Soviet pressure, Cho was obliged to reorganize the Provisional People's Committee for the Five Provinces, and accept more communists onto the councils.[23] The opposing ideologies of Kim and Cho led to a clash between the two men, and the forced power-sharing failed to sit well with either of them.

The 1945 Moscow Conference between the victorious Allies discussed the statehood of Korea, proposing a four-power trusteeship for a period of five years, after which Korea would become an independent state. For Cho, this would result in excessive foreign, and particularly communist, influence over his country, and he refused to co-operate.[24] On 1 January 1946, Andrey Alekseyevich Romanenko, a Soviet leader, met with Cho and tried to persuade him to sign support of the trusteeship. Cho however, refused to sign support.[25] After Soviet leaders realized that they could not persuade Cho to endorse Soviet trusteeship, they lost all remaining hope of Cho becoming a prominent North Korean leader reflecting Soviet ideals.[26] On 5 January, Cho was arrested by Soviet soldiers and detained in Pyongyang's Koryo Hotel.[27]

For some time he was kept under comfortable conditions at the Koryo Hotel, from which position he continued to vocally oppose the communists. He stood in the 1948 vice-presidency election, but by then the Communist influence in the country's affairs was too strong, and he was unsuccessful, receiving only 10 votes from the National Assembly. Cho was later transferred to a prison in Pyongyang, where confirmed reports of him end. He is generally believed to have been executed along with other political prisoners during the early days of the Korean War, possibly in October 1950.[28] Cho's removal opened the way for Kim Il-sung to consolidate his power in the north, a position he was able to hold for 48 years until his death in 1994.

Legacy

In 1970, Cho's deeds gained posthumous recognition when South Korean government awarded him the Order of the Republic of Korea in the Order of Merit for National Foundation.[29] The taekwondo form Ko-Dang was named in honour of Cho Man-sik.[30]

References

- Lankov, "From Stalin to Kim Il Sung", p23

- "[특별 기고]유계준ㆍ유기진 장로, 유기천 총장". 미주중앙일보. 8 November 2007. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- "평양대부흥". www.1907revival.com. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- "[미래를 여는 한국교회] 서울 산정현교회는 빛나는 신앙 전통 계승". news.kmib.co.kr (in Korean). 8 February 2010. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- Lankov, "From Stalin to Kim Il Sung", p10

- Wells, "New God, New Nation", p142

- Wells, "New God, New Nation", p87

- Eckert, "Korea, Old and New", p292

- Lankov, "From Stalin to Kim Il Sung", p11

- Wells, "New God, New Nation", p19

- Wells, "New God, New Nation", p142

- Wells, "New God, New Nation", p143

- K., Armstrong, Charles (2003). The North Korean revolution, 1945-1950. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801440149. OCLC 49891551.

- Kim, The History of Korea, p142

- Armstrong, "The North Korean Revolution", p68

- Ree, "Socialism in One Zone", p87

- Lee, The Partition of Korea, p133

- Lankov, "From Stalin to Kim Il Sung", p14

- Wells, "New God, New Nation", p137

- Lankov, "From Stalin to Kim Il Sung", p14

- Lankov, "From Stalin to Kim Il Sung", p14

- Lankov, "From Stalin to Kim Il Sung", p22

- Lee, The Partition of Korea, p135

- Lee, The Partition of Korea, p145

- Ree, "Socialism in One Zone", p143

- Lankov, "From Stalin to Kim Il Sung", p24

- Lankov, "From Stalin to Kim Il Sung", p23

- Armstrong, "The North Korean Revolution", p123

- Movement Activists, Independence Hall of Korea, retrieved 14 November 2008

- Choi, Hong-hi (1972), Tae Kwon Do: Art Of Self Defence, International Taekwon-Do Federation, ISBN 978-1-897307-76-2

Bibliography

- Armstrong, Charles; Post, Jerrold (2004), The North Korean Revolution, 1945-1950, Cornell University Press, ISBN 0-8014-8914-8

- Eckert, Carter (1990), Korea, Old and New: A History, Seoul: The Korea Institute, Harvard University, ISBN 0-9627713-0-9

- Kim, Chun-gil (2005), The History of Korea, London: Greenwood, ISBN 0-313-33296-7

- Lankov, Andrey (2002), From Stalin to Kim Il Song, Hurst & Co, ISBN 1-85065-563-4

- Lee, Jong-soo (2006), The Partition of Korea after World War II, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 1-4039-6982-5

- Oliver, Robert (1989), Leadership in Asia: Persuasive Communication in the Making of Nations, 1850-1950, University of Delaware Press, ISBN 0-87413-353-X

- Pratt, K.L.; Hoare, J.; Rutt, R. (1999), Korea: A Historical and Cultural Dictionary, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-7007-0464-4

- Ree, Erik (1989), Socialism in One Zone: Stalin's Policy in Korea, 1945-1947, Oxford: Berg, ISBN 0-85496-274-3

- Wells, Kenneth (1990), New God, New Nation: Protestants and Self-reconstruction Nationalism in Korea, 1896-1937, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0-8248-1338-3

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cho Man-sik. |