City block

A city block, residential block, urban block or simply block is a central element of urban planning and urban design.

A city block is the smallest group of buildings that is surrounded by streets, not counting any type of thoroughfare within the area of a building or comparable structure. City blocks are the space for buildings within the street pattern of a city, and form the basic unit of a city's urban fabric. City blocks may be subdivided into any number of smaller land lots usually in private ownership, though in some cases, it may be other forms of tenure. City blocks are usually built-up to varying degrees and thus form the physical containers or 'streetwalls' of public space. Most cities are composed of a greater or lesser variety of sizes and shapes of urban block. For example, many pre-industrial cores of cities in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East tend to have irregularly shaped street patterns and urban blocks, while cities based on grids have much more regular arrangements.

Grid plan

In most cities of the world that were planned, rather than developing gradually over a long period of time, streets are typically laid out on a grid plan, so that city blocks are square or rectangular. Using the perimeter block development principle, city blocks are developed so that buildings are located along the perimeter of the block, with entrances facing the street, and semi-private courtyards in the rear of the buildings.[1] This arrangement is intended to provide good social interaction among people.[1]

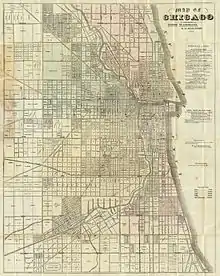

Since the spacing of streets in grid plans varies so widely among cities, or even within cities, it is difficult to generalize about the size of a city block. Oblong blocks range considerably in width and length. The standard block in Manhattan is about 264 by 900 feet (80 m × 274 m). In Chicago, a typical city block is 330 by 660 feet (100 m × 200 m),[2] meaning that 16 east-west blocks or 8 north-south blocks measure one mile, which has been adopted by other US cities. The blocks in central Melbourne, Australia, are also 330 by 660 feet (100 m × 200 m), formed by splitting the square blocks in an original grid with a narrow street down the middle.

Many world cities have grown by accretion over time rather than being planned from the outset. For this reason, a regular pattern of even, square or rectangular city blocks is not so common among European cities, for example. An exception is represented by those cities that were founded as Roman military settlements, and that often preserve the original grid layout around two main orthogonal axes. One notable example is Turin, Italy. Following the example of Philadelphia, New York City adopted the Commissioners' Plan of 1811 for a more extensive grid plan. By the middle of the 20th century, the adoption of the uniform, rectilinear block subsided almost completely, and different layouts prevailed, with random sized and either curvilinear or non-orthogonal blocks and corresponding street patterns.

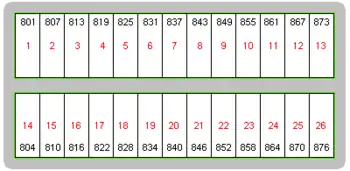

In much of the United States and Canada, the addresses follow a block and lot number system, in which each block of a street is allotted 100 building numbers.

Structure variations

The concept of city block can be generalized as a superblock or sub-block.

Superblock

A superblock, or super-block, is an area of urban land that is bounded by arterial roads and the size of multiple typically-sized city blocks. Within the superblock, the local road network, if any, is designed to serve only local needs.

Definitions and typologies

Within the broad concept of a superblock, various typologies emerge based primarily on the internal road networks within the superblock, their historical context, and whether they are auto-centric or pedestrian-centric. The context in which superblocks are being studied or conceived gives rise to varying definitions.

An internal road network characterised by cul-de-sacs is typical of auto-centric suburban development primarily in Western countries throughout the 20th century. The Oxford Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture's definition is rooted within this typically suburban conception:

“Area containing residential accommodation, shops, schools, offices, etc., with public open space (e.g. a green), surrounded by roads and penetrated by cul-de-sac service-roads. It is linked to other super-blocks and a town centre by means of paths over or under the roads (e.g. in Radburn planning).”[3]

Though the aim of such superblocks is generally to minimise traffic within the superblock by directing it to arterial roads, the effect in many cases has been to entrench automobile dependence by limiting pedestrian permeability. Superblocks can also contain an orthogonal internal road network, including those based on a grid plan or quasi-grid plan. That typology is prevalent in Japan and China, for example. Chen defines the supergrid and superblock urban morphology in that context as follows:

“The Supergrid is a large-scale net of wide roads that defines a series of cells or Superblocks, each containing a network of narrower streets.”[4]

Superblocks can also be retroactively superimposed on pre-existing grid plan by changing the traffic rules and streetscape of internal streets within the superblock, as in the case of Barcelona's superilles (Catalan for superblocks). Each superilla has nine city blocks, with speed limits on the internal roads slowed to 10–20 km/h, through traffic disallowed, and through travel possible only on the perimeter roads.[5]

In Soviet Union and post-Soviet states, a technical term out of construction industry is "residential massíve" (Russian: Жилой массив, Zhyloi massiv). According to the definition, a residential massíve consists of several of residential quarters (city blocks) that are associated by one architectural design (concept).[6] In a number of cities in post-Soviet countries, several city neighborhoods have names like massiv or masyv and appeared in the second half of the 20th century with the rapid expansion of cities. In Central Europe, which was once in the Warsaw Pact, several cities have residential areas filled with inexpensive housing of multi-story buildings known as panelák (panel buildings). Panel buildings of similar architectural type may be erected as one residential city quarter or bigger residential area as massíve.

Superblocks in North America, the United Kingdom, and Australia

Superblocks were popular during the early and mid-20th century auto-centric suburban development. They arose from modernist ideas in architecture and urban planning. Planning was then based upon the distance and speed scales for the automobile and discounted the pedestrian and cyclist modes, as obsolete transportation vehicles. A superblock is much larger than a traditional city block, with a greater setback for buildings, and is typically bounded by widely spaced, high-speed, arterial or circulating routes, rather than by local streets. Superblocks are often found in suburbs or planned cities or are the result of urban renewal of the mid-20th century in which a street hierarchy has replaced the traditional grid. In a residential area of a suburb, the interior of the superblock is typically served by dead-end or looped streets. The discontinuous streets served the automobile, as longer distances and the extra fuel required to go between destinations were not concerns, but at the pedestrian scale, the discontinuity of the roads added to the distance that must be traveled. The discontinuity inside the superblock forced automobile dependency, discouraged errand walking, and forced more traffic onto the fewer continuous streets. That increased demand for through streets, which led ultimately to the streets having more travel lanes added for cars and made it more difficult for any pedestrian to cross such streets. In that way, superblocks cut up the city into isolated units, expanded automobile dominance, and made it impossible for pedestrians and cyclists to get anywhere outside of the superblock. Superblocks can also be found in central city areas, where they are more often associated with institutional, educational, recreational and corporate rather than residential uses.

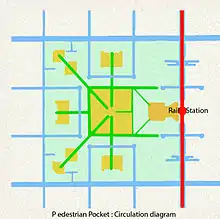

The urban planner Clarence Perry argued for use of superblocks and related ideas in his "neighborhood unit" plan, which aimed to organize space in a way that was more "pedestrian-friendly" and provided open plazas and other space for residents to socialize. Planners, today, now know that the street discontinuity and the multi-lane roads associated with superblocks have caused the decline of pedestrian and bicycle use everywhere with the "sprawl" pattern. The traditional urban block diffused automobile traffic onto several narrower roads at slower speeds. That more finely connected network of narrower roads better allowed the pedestrian and cyclist realms to flourish. The superblock, at the scale suitable only for automobiles, and not pedestrians, was the means for ultimate automobile dominance by the end of the 20th century.[7] The same intention to facilitate pedestrian movement and socializing is captured by an influential 1989 conceptual design of a Pedestrian Pocket[8] (see diagram). It is, similarly, a superblock composed of nine normal city blocks clustered around a light rail station and a central open space. Its circulation pattern consists primarily of a dense pedestrian network which is complementary to but independent from the car network. Access by car is provided by means of three loops. This superblock differs from Perry's concept in that it makes it impossible for cars to traverse it rather than very difficult; it is car-impermeable.

In the 1930s, superblocks were often used in urban renewal public housing projects in American cities.[9] In using superblocks, housing projects aimed to eliminate back alleys, which were often associated with slum conditions.[9]

Superblocks are also used when functional units such as rail yards or shipyards, inherited from the 19th and early 20th centuries, are too big to fit in an average city block. A contemporary function which reflects ancient practices that also requires larger than typical blocks is the sports stadium or arena. Just as the Colosseum in ancient Rome, sports complexes require superblocks. The Providence Park stadium in Portland, for example, takes up four normal city blocks as does the equally large Greensboro Coliseum in North Carolina. Other contemporary institutions, establishments or functions that use superblocks are: city halls like Government Center, Boston and Toronto City Hall; regional general hospitals or specialized medical centres; convention and exhibition centers, such as Exhibition Place in Toronto and the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center; and downtown enclosed Shopping Malls such as Eaton Centre in Toronto, echoing the large gallerias of the 19th century. Cultural complexes, such as the Lincoln Center in New York City, often occupy a superblock achieved through the consolidation of regular city blocks. A recent superblock user is the merchandise distribution centre, which can range in area from one to ten city blocks.

Most notably, however, the largest superblocks in contemporary cities are used by university and college campuses such as Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of Illinois at Chicago, the City College of New York, Columbia University and the University of Alberta in Edmonton. The "campus" impact on the city block structure is quite prominent particularly in small university towns such as Waterloo, Ontario or Ithaca, New York where the university superblock counts for a sizeable portion of the total city area. Campuses, in general, are fully walkable and sociable environments within the superblock structure. On some university campuses the extensive and exclusive pedestrian path network at grade is supplemented with below grade paths. New Urbanists would argue that separating circulation modes effectively kills the social interaction that bolsters urban areas.

Additional users of the superblock concept are large national or multinational corporations who constructed campuses in the late 1900s and 2000s. Examples of superblock campuses include Google in Mountain View, California; and Apple and Hewlett-Packard in San Jose, California. Another well-known commercial superblock is the World Trade Center site in New York City, where several streets of Manhattan's downtown grid were removed and de-mapped to make room for the center.

Social and housing agencies in the U.S., Canada and the UK used the superblock model for large housing projects such as Regent Park in Toronto and Benny Farm in Montreal, Canada. In New York City, the Stuyvesant Town private market, residential development superblock takes up about 18 normal city blocks and provides a large green amenity for its residents and neighbours. It uses crescent (loop) rather than dead-ended streets inside the superblock and an extensive network of paths that provide excellent connectivity within the block and to the neighbouring areas (see drawing).

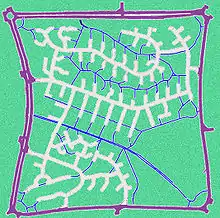

Where the superblock is used for housing projects like Stuyvesant Town, the advantages sought are an improved separation of vehicular and pedestrian circulation, enhanced tranquility and reduced accident risk within the neighbourhood. In 2003, Vauban (a rail suburb of Freiburg, Germany) was constructed with similar goals.[10] Its layout consists mainly of a superblock with a central pedestrian spine and a few narrow looped and dead-ended streets. The British new town of Milton Keynes is built around a grid of one-kilometre square superblocks (see drawing).

Superblocks have been proposed as a potential solution to road space prioritisation and increased pedestrian flows in the CBD of Melbourne, Australia. The City of Melbourne's 2018 Transport Discussion Paper: City Space suggests, based on the example of Barcelona's superilles, that “‘Superblocks’ could be applied in Melbourne to make streets in the central city safer, greener, more inclusive and more vibrant.”

Barcelona's super·illes

The superblock concept has been applied retroactively in Barcelona's La Ribera and Gràcia districts, which both have a medieval street network with narrow and irregular streets, since 1993. In these two cases it resulted in an increase of journeys on foot (over 10%) and by bicycle (>15%) and in a higher level of commercial and service activity.[11]

Superblocks, or super·illes in the native Catalan, are now being superimposed in the Eixample District's famous Ildefons Cerdà-designed late 19th century grid plan.[5] Each superilla comprises nine city blocks, or illes, in which the internal traffic flows have been altered to disallow through traffic, and speed limits on internal roads reduced. After entering a superilla from a perimeter road, vehicles are only able to circumnavigate one city block and return out to the same perimeter road again, meaning that local access to garages and businesses is maintained, but making it impossible to cut through to the other side. Speed limits have also been reduced to 20 km/h initially. It was estimated that this could be implemented city-wide for less than €20 million, simply by changing traffic signals.[12]

It is planned to further reduce speeds to 10 km/h and remove on-street parking by building more off-street car parks. This is intended to make the internal streets safer for pedestrians and create more space for playing games, sports, and cultural activities such as outdoor cinemas.[12]

The concept was initially spurred by a redesign of the city's bus network that consolidated bus routes into a simpler orthogonal network, with more frequent services.[12] With many streets freed from buses as a result, and the idea was formulated to create the superilles in order to reduce traffic, cut the high levels of air and noise pollution in the city, and reallocate space to pedestrians and cyclists. The superilles have been met with criticism and resistance from some residents however, who have complained about the dramatically increased distance for some previously short car trips, and the increased traffic on the arterial perimeter roads.[13]

Superblocks in Japan

Superblocks have been the prevalent mode of urban land use planning in Japan, even being described as the "sine qua non of Japanese urban design",[14] present in all medium to large Japanese cities to a greater or lesser degree. Cities are typically arranged around a system of wide arterial roads, often approximating a grid and flanked by generous sidewalks, and an orthogonal network of narrow internal streets, normally operating as shared zones with no sidewalks. The grid plan layout of Japanese cities such as Kyoto and Nara dates back to the eighth century, which were in turn derived from Chinese grid models.[15] The system of superblocks were created mostly in the early to mid 20th century by physically widening arterial roads, superimposing the supergrid and superblock structure in a physical sense. This contrasts with the Barcelona model wherein the superblock model was imposed through changed traffic signalling rather than physical street widening. They further contrast to Western auto-centric models described above as they are typically characterised by highly walkable and cycle-able street networks, featuring high-density mixed use development and supported by highly effective and efficient public transport systems.

Resulting largely from planning controls which link building height with street width, Japanese superblocks are typically characterised by a ‘hard shell’ of tall buildings with commercial uses along the perimeter arterial roads, with a ‘soft yolk’ of low-rise residential use in the centre.[16]

The spatial structure of superblocks can also be analysed, per a taxonomy detailed by Barrie Shelton,[15] through the classification of roads as ‘global’, being the arterial roads which provide for cross-city travel, ‘local’ roads, which provide local access to buildings within the superblock, and ‘glocal’ roads, which may cross the entire superblock, allowing through travel, and in many instances into neighbouring superblocks. Glocal roads differ from global roads however, in that they are narrow, have lower speed limits, and do not form part of the ‘supergrid’ structure. Shelton also describes the sidewalks of the global arterial roads as functioning as streets in themselves, or ‘sidewalk streets’, operating in a similar manner to the local streets.

Sub-structure

In a geoprocessing perspective there are two complementary ways of modeling city blocks:

- with sidewalks: using a direct geometric representation of the usual concept of city blocks. Not only sidewalks, but also inner alleys, common gardens, etc. Some street parts, such as a street greenway, isolated and with no related lot, can be also represented as a block without sidewalks.

- without sidewalks: represented by polygon obtained by the external border of the union of a set of touching land lots (illustration opposite).

Always a block without sidewalks is within a block with sidewalks. The geometric subtraction of a block without sidewalks from block with sidewalks, contains the sidewalk, the alley, and any other non-lot sub-structure.

Perimeter block

A perimeter block is a type of city block which is built up on all sides surrounding a central space that is semi-private. They may contain a mixture of uses, with commercial or retail functions on the ground floor. Perimeter blocks are a key component of many European cities and are an urban form that allows very high urban densities to be achieved without high-rise buildings.[17]

Uses

As an informal unit of distance

In North American English and Australian English, the word "block" is used as an informal unit of distance.[18] For example, someone giving directions might say, "It's three blocks from here".

Online

There have been online innovations and websites such as msnbc.com-owned EveryBlock, which uses geo-specific feeds from neighborhood blogs, Flickr, Yelp, Craigslist, YouTube, Twitter, Facebook and other aggregated data to give readers a picture of what is going on in their town or neighborhood down to the block.[19]

See also

- Census block

- Grid plan

- Manhattan distance

- Urban design

- Urban planning

References

- Frey, Hildebrand (1999). Designing the City: Towards a More Sustainable Urban Form. E & FN Spon. ISBN 978-0-419-22110-4.

- https://www.cityofchicago.org/dam/city/depts/cdot/StreetandSitePlanDesignStandards407.pdf

- Curl, James Stevens (2006). A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, 2ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. super-block. ISBN 978-0-19-172648-4.

- Xiaofei, Chen (2017-08-29). "A Comparative Study of Supergrid and Superblock Urban Structure in China and Japan Rethinking the Chinese Superblocks: Learning from Japanese Experience". hdl:2123/17986. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Bausells, Marta (2016-05-17). "Superblocks to the rescue: Barcelona's plan to give streets back to residents". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-04-14.

- Understanding about residential massíve. Round calendar planning of residential massíve development by urban-planned complexes (Понятие о жилых массивах. Календарные планы застройки жилых массивов градостроительными комплексами).

- Keating, W. Dennis, Norman Krumholz (2000). "Neighborhood Planning". Journal of Planning Education and Research. 20 (1): 111–114. doi:10.1177/073945600128992546.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "The Pedestrian Pocket Book: A New Suburban Design Strategy - Calthorpe Associates". www.calthorpe.com. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- Ben-Joseph, Eran, Terry S. Szold (2005). Regulating Place: Standards and the Shaping of Urban America. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-94874-6.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment http://www.cabe.org.uk/case-studies/vauban

- "Barcelona Metropolis - Salvador Rueda - Sustainable Urban Expansions: the Legacy of the Cerdà Plan". lameva.Barcelona.cat. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- "Superblocks, Barcelona Answer to Car-Centric City – Cities of the Future". Cities of the Future. 2016-07-21. Retrieved 2018-04-14.

- "Barcelona's Car-Taming Superblock Plan Faces a Backlash". CityLab. Retrieved 2018-04-14.

- Shelton, Barrie (2012). Learning from the Japanese city : looking East in urban design. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 141. ISBN 9780415554398.

- Shelton, Barrie (2012). Learning from the Japanese city: looking East in urban design. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 142. ISBN 9780415554398.

- Popham, Peter (1985) Tokyo: the City at the End of the World. Tokyo: Kodansha International, p. 48, cited in Shelton, Barrie (2012) Learning from the Japanese city : looking East in urban design. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, p. 8.

- Edwards, Brian: "The European perimeter block" in Courtyard Housing: Past, Present and Future, Taylor & Francis, 2004

- Imagination: The Science of Your Mind's Greatest Power, by Jim Davies

- "Web Publishing Roll-Up: Rise and Advise". CMSWire.com. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

Further reading

- Jacobs, Jane (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Random House.

- The Great American Grid: Block Size Dimensions

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to City blocks. |