Civic Center Plaza

Civic Center Plaza, also known as Joseph Alioto Piazza, is the 4.53-acre (1.83 ha) plaza immediately east of San Francisco City Hall in Civic Center, San Francisco, in the U.S. state of California.[1][2] Civic Center Plaza occupies two blocks bounded by McAllister, Larkin, Grove, and Carlton B. Goodlett (the section of Polk between City Hall and the plaza was renamed for Dr. Goodlett in 1999), divided into a north block and south block by the former alignment of Fulton Street. The block north of Fulton is built over a three-story parking garage (completed in 1960); the block south of Fulton lies over a former exhibition space, Brooks Hall (completed in 1958).

| Civic Center Plaza | |

|---|---|

| Joseph L. Alioto Performing Arts Piazza | |

The plaza with San Francisco City Hall in the background, March 2008 | |

| |

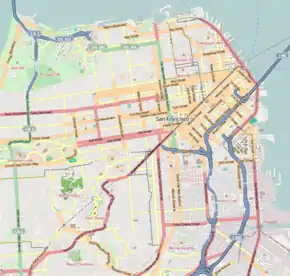

| Location | Civic Center |

| Nearest city | San Francisco |

| Coordinates | 37.7795°N 122.4176°W |

| Area | 4.53 acres (1.83 ha)[1] |

| Created | 1911 |

| Designer | John Galen Howard |

| Designation | Civic Center National Historic Landmark District |

| Public transit access | Muni Metro/BART (Civic Center) |

Design

.jpg.webp)

According to the San Francisco Recreation & Parks Department, the size of Civic Center Plaza ranges from 4.53 to 5.38 acres (1.83 to 2.18 ha).[1][3] Civic Center Plaza is approximately symmetrical from north to south (across an imaginary east-west line drawn along the former route of Fulton Street). Through the center of the plaza, two aisles of London plane trees flank an east-west pathway leading to City Hall, with formal plantings north and south of the tree aisle. The plaza was reconstructed starting in 1956 to build two underground structures: Brooks Hall and a parking garage. There are two play structures which opened in 1999[4] and were refurbished in 2017 on the east (Larkin) side of the plaza, one in the northeast corner, and one in the southeast corner.

Brooks Hall

Brooks Hall, an underground space connected to the basement level of Bill Graham Civic Auditorium, was the main exhibition space for the City of San Francisco from its completion in 1958 until 1981, when the first phase of Moscone Center was completed.[5] Over the course of its history, several notable computer shows held their inaugural events at Brooks Hall, including the West Coast Computer Faire (1977)[6] and Macworld (1985).[7] It is currently used to store materials from the nearby Main Library and other historical artifacts, including the disassembled Exhibition Organ, a pipe organ which was donated to San Francisco for the 1915 Panama–Pacific International Exposition.[5]

Parking garage

A three-story parking garage was completed under the north block of the plaza in 1960. Access to the garage is provided by ramps on McAllister and Larkin. Overall dimensions of the parking garage are 317 by 374 feet (97 m × 114 m) and the floor-to-ceiling clearance ranges from 10 feet (3.0 m) on the uppermost level to 9 feet 3 inches (2.82 m) on the two lower levels. The structure rests on a concrete slab varying in thickness from 3 to 5 5⁄6 feet (0.91 to 1.78 m) thick.[8]

The parking structure was designed by Gould and Degenkolb.[8]

Playgrounds

The playgrounds near Larkin were first installed in 1993 (north) and 1998 (south)[9] as part of the remodeling of City Hall completed in 1999.[4] They were shut down and renovated in 2017 at a cost of $10 million, funded by a grant from the Helen Diller Family Foundation (administered by The Trust for Public Land), and reopened in February 2018, when they were renamed the Helen Diller Civic Center Playgrounds.[10] The remodeled Helen Diller Playgrounds were designed by Andrea Cochran Landscape Architecture and used concepts that drew inspiration from local weather phenomena, including Karl the fog.[10][9] Artificial grass is installed to cut water use, and the playgrounds are under constant surveillance.[11]

History

.jpg.webp)

After San Francisco was selected in 1911 to host the 1915 Panama–Pacific International Exposition, numerous civic improvements were proposed, and a commission was set up to judge entries for a City Hall design competition. The jurors on the commission were John Galen Howard, Frederick W. Meyer, and John Reid, Jr.[12] An early design by A. Lacy Warswick, a city architect, called for twin fountains along the north-south centerline of the plaza.[13]:12–14

Camp Agnos

The plaza has had a history as a congregation spot for homeless people, driven in part by its proximity to the Tenderloin District. A tent city in Civic Center Plaza had existed for years prior to 1989.[14] Art Agnos campaigned on a promise to treat the homeless more humanely and won the campaign for Mayor of San Francisco in 1987. After he assumed office, a large influx of homeless people started to move into Civic Center Plaza during the summer of 1989, prompting some to dub the new tent city Camp Agnos. The preceding mayor, Dianne Feinstein, had periodically ordered people to be removed from the plaza; in contrast, Agnos's campaign pledge exposed him to criticism after the homeless were described to be aggressively panhandling visitors. As a compromise, in July of that year, Agnos ordered police to remove tents and makeshift shelters but not the homeless residents.[14]

Following the October 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, some residents of San Francisco were forced to camp outdoors while buildings were inspected; more destitute citizens were forced out of their subsidized single room occupancy hotels and many made their way to Camp Agnos.[15] Agnos again ordered encampments removed in July 1990, but refused to move the homeless people to another site until two permanent shelters could be built, which opened later that year.[16][17] The long delay in opening shelters and the mayor's seeming acceptance of Camp Agnos contributed to Agnos's defeat in the re-election campaign of 1991.[18]

City Hall gilding

Civic Center Plaza was dedicated as the Joseph L. Alioto Performing Arts Piazza to honor former mayor Joseph Alioto on October 28, 1998. A spokesperson for Mayor Willie Brown stated "It will be an area where people can sing opera, recite poetry, do all the things Mayor Alioto was so enamored of". Alioto had died earlier in 1998.[19]

As part of the initiative started by Mayor Brown to remodel City Hall, a refurbished Civic Center Plaza was unveiled in January 1999, including two new playgrounds; police patrols were deployed under a new policy to roust the homeless, who generally moved two blocks east to UN Plaza.[4] Public concerts were scheduled as part of the effort to change the unsavory reputation of Civic Center Plaza. At the time, it was announced that plans for a permanent remodeling of the plaza were being prepared.[4]

Redesign

In 2018, city officials started accepting proposals to redesign the plaza.[20]

References

- "Civic Center Plaza (Joseph Alioto Piazza)". San Francisco Department of Recreation and Parks. Retrieved 2018-10-03.

- "Civic Center Plaza". San Francisco Parks Alliance. 2012-05-10. Retrieved 2018-10-03.

- "Joseph L. Alioto Performing Arts Piazza". San Francisco Department of Recreation and Parks. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- Epstein, Edward (January 5, 1999). "S.F. Police Sweep Freshly Cleaned Civic Center Plaza / Homeless complain about patrols". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- "Abandoned Convention Hall Part Of Civic Center Revitalization Plan". Hoodline. January 4, 2018. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- Mancuso, Jo (September 8, 1996). "Grouping in the Dark". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- Webster, Bruce (July 1985). "According to Webster: Start-up". BYTE. pp. 367–383. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- Simon Martin Vegue Winkelstein Moris Olin Partnership (May 1998). "III. Engineering Conditions". San Francisco Civic Center Historic District Improvement Project: Site Analysis Resource Notebook (PDF) (Report). Department of Public Works, City and County of San Francisco. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- "Helen Diller Civic Center Playgrounds" (PDF). San Francisco Department of Recreation & Parks. 7 October 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- Sisto, Carrie (February 5, 2018). "Renovated Civic Center Playgrounds Open On Valentine's Day". hoodline. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- Rubenstein, Steve (February 16, 2018). "$10 million playgrounds give downtown SF kids a safe place to frolic". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- "Civic Center Plaza - San Francisco". The Cultural Landscape Foundation. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- Civic Center Proposal (PDF) (Report). City and County of San Francisco, Office of Mayor Dianne Feinstein. November 1987. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- Basheda, Valarie (July 21, 1989). "S.F. Clears Park's Tent City of Structures, Not People". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- Agnos, Art (March 8, 2016). "Editorial: What was 'Camp Agnos' anyway?". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- "San Francisco's Mayor Ousts Homeless Camp". The New York Times. AP. July 6, 1990. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- Lelchuk, Ilene (September 7, 2003). "S.F.'s Homeless Legacy / Two decades of failure". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- Cannon, Lou (December 12, 1991). "San Francisco Mayor Loses in Upset". The Washington Post. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- Hendrix, Anastasia; Dougan, Michael (October 29, 1998). "Patch of City named for Mayor Alioto". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- "Public input sought on redesign of SF's Civic Center Plaza". The San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 2018-10-03.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Civic Center Plaza (San Francisco). |

- "Helen Diller Playgrounds at Civic Center Improvements". San Francisco Department of Recreation & Parks. 2018.