Coit Tower

Coit Tower is a 210-foot (64 m) tower in the Telegraph Hill neighborhood of San Francisco, California, offering panoramic views over the city and the bay. The tower, in the city's Pioneer Park, was built between 1932 and 1933 using Lillie Hitchcock Coit's bequest to beautify the city of San Francisco. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on January 29, 2008.[1]

Coit Memorial Tower | |

Coit Tower with statue of Columbus in foreground | |

Coit Tower  Coit Tower  Coit Tower | |

| Location | 1 Telegraph Hill Blvd. San Francisco, California |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°48′09″N 122°24′21″W |

| Area | 1.7 acres (0.69 ha) |

| Built | 1933 |

| Architect | Brown, Arthur Jr. |

| Architectural style | Art Deco |

| NRHP reference No. | 07001468[1] |

| SFDL No. | 165 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | January 29, 2008 |

| Designated SFDL | 1984[2] |

The art deco tower, built of unpainted reinforced concrete, was designed by architects Arthur Brown, Jr. and Henry Howard. The interior features fresco murals in the American Social Realism style, painted by 25 different onsite artists and their numerous assistants, plus two additional paintings installed after creation offsite.

Also known as the Coit Memorial Tower, it was dedicated to the volunteer firemen who had died in San Francisco's five major fires.[3] Although an apocryphal story claims that the tower was designed to resemble a fire hose nozzle[4] due to Coit's affinity with the San Francisco firefighters of the day, the resemblance is coincidental.[5]

History

Telegraph Hill, the tower's location, has been described as "the most optimal 360 degree viewing point to the San Francisco Bay and five surrounding counties."[6] In 1849, it became the site of a two-story observation deck, from which information about incoming ships was broadcast to city residents using an optical semaphore system, replaced in 1853 by an electrical telegraph that was destroyed by a storm in 1870.[6]

Coit Tower was paid for with money left by Lillie Hitchcock Coit (1843–1929), a wealthy socialite who loved to chase fires in the early days of the city's history. Before December 1866, there was no city fire department, and fires in the city, which broke out regularly in the wooden buildings, were extinguished by several volunteer fire companies. Coit was one of the more eccentric characters in the history of North Beach and Telegraph Hill, smoking cigars and wearing trousers long before it was socially acceptable for women to do so. She was an avid gambler and often dressed like a man in order to gamble in the males-only establishments that dotted North Beach.[7]

Coit's fortune funded the monument four years following her death in 1929. She had a special relationship with the city's firefighters. At the age of fifteen she witnessed the Knickerbocker Engine Co. No. 5 in response to a fire call up on Telegraph Hill when they were shorthanded; she threw her school books to the ground and pitched in to help, calling out to other bystanders to help get the engine up the hill to the fire, to get the first water onto the blaze. After that Coit became the Engine Co. mascot and could barely be constrained by her parents from jumping into action at the sound of every fire bell. She frequently rode with the Knickerbocker Engine Co. 5, especially in street parades and celebrations in which the Engine Co. participated. Through her youth and adulthood Coit was recognized as an honorary firefighter.

In her will she specified that one third of her fortune, amounting to $118,000,[6] "be expended in an appropriate manner for the purpose of adding to the beauty of the city which I have always loved."[8] Two memorials were built in her name. One was Coit Tower, and the other was a sculpture depicting three firemen, one of them carrying a woman in his arms.[9]

The San Francisco County Board of Supervisors proposed that Coit's bequest be used for a road at Lake Merced. This proposal brought disapproval from the estate's executors, who expressed a desire that the county find "ways and means of expending this money on a memorial that in itself would be an entity and not a unit of public development".[6] Art Commission president Herbert Fleishhacker suggested a memorial on Telegraph Hill, which was approved by the estate executors. An additional $7,000 in city funds was appropriated, and a design competition was initiated. The winner was architect Arthur Brown, Jr, whose design was completed and dedicated on October 8, 1933.[6]

Coit Tower was listed as a San Francisco Designated Landmark in 1984[2] and on the National Register of Historic Places in 2008.[1] Although Coit Tower is not technically a California Historical Landmark, the state historical plaque for Telegraph Hill is located in the tower's lobby, marking the site of the original signal station.[10]

The San Francisco Arts Commission ordered the removal of the Statue of Christopher Columbus that has stood outside the entrance of the tower since 1957 on June 18, 2020, following numerous other removals of controversial statues during the George Floyd protests that began in May 2020.[11]

Architecture

Brown's competition design envisioned a restaurant in the tower, which was changed to an exhibition area in the final version. The design uses three nesting concrete cylinders, the outermost a tapering fluted 180-foot (55 m) shaft that supports the viewing platform. An intermediate shaft contains a stairway, and an inner shaft houses the elevator. The observation deck is 32 feet (9.8 m) below the top, with an arcade and skylights above it. A rotunda at the base houses display space and a gift shop.[6]

Mural project

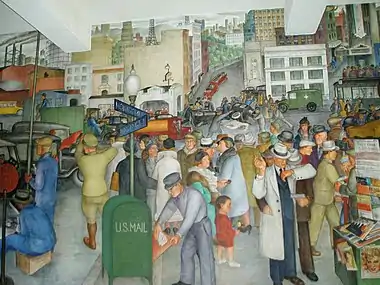

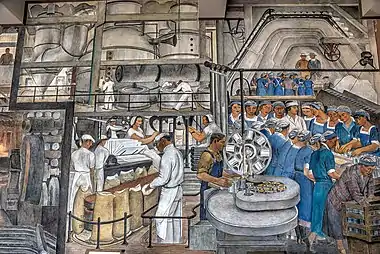

The Coit Tower murals in the American Social Realism style formed the pilot project of the Public Works of Art Project,[6] the first of the New Deal federal employment programs for artists. Ralph Stackpole and Bernard Zakheim successfully sought the commission in 1933, and supervised the muralists, who were mainly faculty and students of the California School of Fine Arts (CSFA), including Maxine Albro, Victor Arnautoff, Ray Bertrand, Rinaldo Cuneo, Mallette Harold Dean, Gordon Langdon, Clifford Wight, Edith Hamlin, George Albert Harris, Otis Oldfield, Suzanne Scheuer,[13] Hebe Daum, Jane Berlandina, Frederick E. Olmsted Jr., Jose Moya del Pino[14] and Frede Vidar.[15][16][17][18][19][20][21] These 25 artists (chosen by Walter Heil, director of the de Young Museum, together with other officials) were each paid $25 to $45 per week to depict "aspects of life in California."[22] The most well-known of them were assigned sections that were 10 by 36 feet (3.0 by 11.0 m) in size, while less famous artists were confined to 10 by 4 feet (3.0 by 1.2 m).[6]

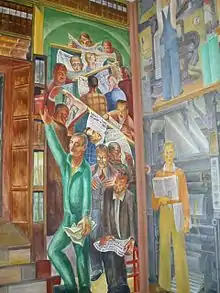

The artists were committed in varying degrees to racial equality and to leftist and Marxist political ideas, which are strongly expressed in the paintings. Bernard Zakheim's mural Library depicts fellow artist John Langley Howard crumpling a newspaper in his left hand as he reaches for a shelved copy of Karl Marx's Das Kapital (here spelled as Das Capital) with his right. Workers of all races are shown as equals, often in the heroic poses of Socialist realism, while well-dressed racially white members of the capitalist classes enjoy the fruit of their labor. Victor Arnautoff's City Life includes the periodicals The New Masses and The Daily Worker in the scene's news stand rack; John Langley Howard's mural depicts an ethnically diverse Labor March as well as showing a destitute family panning for gold while a wealthy, heavily caricatured ensemble observes; and Stackpole's Industries of California was composed along the same lines as an early study of the destroyed Man at the Crossroads.[23]

The youngest of the muralists, George Albert Harris, painted a mural called Banking and Law. In the mural, the world of finance is represented by the Federal Reserve Bank and a stock market ticker (in which stocks are shown as declining) and law is illustrated by a law library.[24] Some of the book titles that appear in the law library, such as Civil, Penal, and Moral Codes, are legitimate, while others list fellow muralists as authors, in a joking or derogatory manner.[25]

After Diego Rivera's Man at the Crossroads mural was destroyed by its Rockefeller Center patrons for the inclusion of an image of Lenin, the Coit Tower muralists protested, picketing the tower. Sympathy for Rivera led some artists to incorporate references to the Rivera incident; in Zakheim's Library panel, Stackpole is painted reading a newspaper headline announcing the destruction of Rivera's mural.[23]

After most of the Coit Tower murals had already been completed, the 1934 West Coast waterfront strike, much of which was taking place nearby at the foot of Telegraph Hill,[25] caused government officials, shipping companies, some union leaders and the press to raise fears about communist agitation.[22] This "red scare" has been identified as playing a "crucial role" in a subsequent controversy that mainly focused on two of the murals; the first being a set of three small frescoes where Clifford Wight portrayed capitalism, the New Deal and communism, the three prominent economic systems of the era, with the communism part containing a hammer and sickle and the caption “Workers of the World Unite.”[22] The second was John Langley Howard's Industry mural (designed with the support of his architect brother Henry Howard), which depicts California industrial scenes including out-of-work men, and angered conservatives by showing a banner of the communist periodical Western Worker above a crowd of workers.[25][26][22] On June 23, 1934, the conservative banker Herbert Fleishhacker, the most powerful member of the committee allocating funds from the Public Works of Art Project, asked Heil to inspect the art, who telegraphed back that some artists had included "details ... and certain symbols which might be interpreted as communistic propaganda,” and that "editors of influential papers ... have warned us that they would take hostile attitude towards whole project unless those details be removed."[22] The official opening of the tower, planned for July 7, was canceled and Fleishhacker ordered to close the tower and to block the view from outside through the windows.[22] Subsequently, articles in the San Francisco Chronicle and The San Francisco Examiner attacked the project, sometimes using misleading representations of the artworks in question, while Wight refused to remove the hammer and sickle symbol from his mural.[22] However, federal government officials decided that the offending parts would need to be painted over, and 16 of the artists signed a statement saying that they opposed the hammer and sickle symbol and that it “has no place in the subject matter assigned.”[22] Eventually, only the hammer and sickle and the "Western Worker" banner were removed, and Coit Tower opened on October 12, 1934.[22]

Two of the murals are of San Francisco Bay scenes. Most murals are done in fresco; the exceptions are one mural done in egg tempera (upstairs, in the last decorated room) and the works done in the elevator foyer, which are oil on canvas. While most of the murals have been restored, a small segment (the spiral stairway exit to the observation platform) was not restored but durably painted over with epoxy surfacing.

Most of the murals are open for public viewing without charge during open hours, although there are ongoing negotiations by the Recreation and Parks Department of San Francisco to begin charging visitors a fee to enter the mural rotunda. The murals in the spiral stairway, normally closed to the public, are open for viewing through tours.[27]

Since 2004 artist Ben Wood collaborated with other artists on large scale video projections onto the exterior of Coit Tower, in 2004, 2006, 2008 & 2009.[28]

The view

The tower, which stands atop Telegraph Hill in San Francisco's Pioneer Park, offers panoramic views of San Francisco including "crooked" Lombard Street, Nob Hill, Russian Hill, Twin Peaks, Aquatic Park, Pier 39, the Financial District, the Ferry Building, as well as San Francisco Bay itself including Angel Island, Alcatraz, Treasure Island, and the Golden Gate and Bay Bridges.

Photographs

A view of Telegraph Hill from a boat in the San Francisco Bay.

A view of Telegraph Hill from a boat in the San Francisco Bay. View of Coit Tower, Alcatraz, and Marin County from Downtown.

View of Coit Tower, Alcatraz, and Marin County from Downtown. A closer photograph of Coit Tower from the parking lot.

A closer photograph of Coit Tower from the parking lot. Coit Tower elevator

Coit Tower elevator View from Lombard Street

View from Lombard Street.jpg.webp) The south-facing side of Coit Tower

The south-facing side of Coit Tower Looking south from the tower

Looking south from the tower Looking up at the tower

Looking up at the tower Coit Tower at night, lit orange in recognition of the San Francisco Giants

Coit Tower at night, lit orange in recognition of the San Francisco Giants View of the bay from Coit Tower

View of the bay from Coit Tower As seen from below

As seen from below Vertical view

Vertical view Detail of arches at the top of the tower

Detail of arches at the top of the tower

In popular culture

Coit Tower was a prominent landscape feature in Alfred Hitchcock's 1958 film, Vertigo, which was set largely in San Francisco. Art director Henry Bumstead, who worked on Vertigo, noted that Hitchcock himself was adamant that Coit Tower should be seen in the film from the apartment of the lead character (portrayed by Jimmy Stewart). When Bumstead asked why, Hitchcock said, "It's a phallic symbol."[29]

Coit Tower was featured in the 1971 Clint Eastwood film Dirty Harry.

Coit Tower appears several times in the dystopic setting of the Tex Murphy game series.

Coit Tower was featured in the finale of The Amazing Race 16 and was the site of a task in which contestants had to use an ascender to climb to the top of the tower.[30]

Coit Tower was featured in the 2010 film Cats & Dogs: The Revenge of Kitty Galore as two dogs venture into the tower to find a pigeon, only to get ambushed by a cat.

Coit Tower features in the first episodes in the television series The Nine Lives of Chloe King as the scene where the main character is pushed off the tower, apparently falling to her death, only to spontaneously come back to life afterwards.

Coit Tower is featured in the episode "The Truth Hurts" (2013) of the Syfy Channel series Warehouse 13.

Coit Tower features in the 2015 disaster film San Andreas as a planned meeting point for some characters after an earthquake has devastated San Francisco.

Coit Tower was also seen on the map sections used in the television series Charmed about a trio of sisters with magic powers to fight demons.

In the 1998 Eddie Murphy film Dr. Dolittle, Murphy's title character talks a suicidal tiger out of jumping off of Coit Tower.

In The Man in the High Castle television series, Ed McCarthy, Robert Childan and Jack hang an antifascist banner from Coit Tower to honour Frank Frink after his execution by the Kenpeitai.

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "City of San Francisco Designated Landmarks". City of San Francisco. Archived from the original on 2014-03-25. Retrieved 2012-10-21.

- California, California State Parks, State of. "COIT MEMORIAL TOWER". CA State Parks. Retrieved 2018-07-29.

- Crowe, Michael F. and Robert W. Bowen (2007). Images of America: San Francisco Art Deco. Arcadia Publishing. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-7385-4734-3.

- "Coit Tower". San Francisco Recreation & Parks Department. Retrieved September 8, 2014.

Contrary to popular belief, Coit Tower was not designed to resemble a firehose nozzle.

- Worsley, Stephen A. (June 18, 2007). "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Coit Memorial Tower". National Park Service. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- "Lillie Hitchcock Coit, 1843-1929". ALMANAC OF AMERICAN WEALTH Wealthy eccentrics. CNN Money. Retrieved April 13, 2014.

- Pryor, Alton (2003). Fascinating Women in California History. Stagecoach Pub. p. 86. ISBN 0-9660053-9-2.

- h2g2 Lillie Hitchcock-Coit – Firefighter

- "Telegraph Hill". Office of Historic Preservation, California State Parks. Retrieved 2012-11-19.

- Fracassa, Dominic (2020-06-18). "San Francisco removes Christopher Columbus statue at Coit Tower ahead of planned protest". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- Remark: The upmost newspaper headlines "Thousands slaughtered in Austria" and dates to "14th February 1934", two days after the outbreak of civil war, lasting only a few days after outlawing the social democratic party.

- http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-suzanne-scheuer-12278

- "Who is Jose Moya del Pino?". Marin Art & Garden Center. Marin Art & Garden Center. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- San Francisco Art Institute. The Commission. SFAI Offers Diego Rivera His Second Commission in the US Archived 2013-09-23 at the Wayback Machine

- http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-jos-moya-del-pino-12903

- http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-maxine-albro-and-parker-hall-12350

- http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-otis-oldfield-13601

- http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-william-hesthal-12752

- https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/wwwprotectcoittower/pages/158/attachments/original/1433545599/JLH_Interview.pdf

- https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/wwwprotectcoittower/pages/158/attachments/original/1434252443/RalphChesseInterview.pdf

- Kamiya, Gary (2017-07-08). "How Coit Tower's murals became a target for anticommunist forces". www.sfchronicle.com. Retrieved 2019-02-03.

- Lee, Anthony W. (1999). Painting on the Left: Diego Rivera, Radical Politics, and San Francisco's Public Murals. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21977-5.

- "Telegraph Hill – Coit Tower Murals". Art and Architecture San Francisco. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- Depression-Era Murals of the Bay Area. Arcadia Publishing. 2014. ISBN 9781467131445.

As the strike raged along the waterfront at the base of Telegraph Hill, many claimed that the labor unrest was influenced by members of the Communist Party. Simultaneously, the PWAP took notice of blatant communist references in the Coit Tower murals painted by Victor Arnautoff, John Langley Howard, Clifford Wight, and Bernhard Zakheim.

- Temko, Allan (November 26, 1999). "John Langley Howard". SFGate. SFGate. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- Whiting, Sam (2014-09-30). "Rare Look at 7 Upstairs Murals at Coit Tower". SFGate. Retrieved 2015-06-23.

- Berton, Justin (November 23, 2009). "Tower of films to recall Alcatraz takeover". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- San Filippo, Maria (November 25, 2002). "Bumstead gives talk on art direction, "˜Vertigo'". The Daily Bruin. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- Franich, Darren (May 10, 2010). "The Amazing Race season finale recap: If You're Going to San Francisco". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coit Tower. |