Claudia Jones

Claudia Jones, née Claudia Vera Cumberbatch (21 February 1915 – 24 December 1964), was a Trinidad and Tobago-born journalist and activist. As a child, she migrated with her family to the US, where she became a Communist political activist, feminist and black nationalist, adopting the name Jones as "self-protective disinformation".[1] Due to the political persecution of Communists in the US, she was deported in 1955 and subsequently lived in the United Kingdom. She founded Britain's first major black newspaper, West Indian Gazette (WIG), in 1958.[2]

Claudia Jones | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Claudia Vera Cumberbatch 21 February 1915 Belmont, Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago |

| Died | 24 December 1964 (aged 49) London, England |

| Resting place | Highgate Cemetery |

| Nationality | Trinidadian |

| Other names | Claudia Cumberbatch Jones |

| Occupation | Journalist, activist |

| Years active | 1936–1964 |

| Political party | Communist Party USA |

Early life

Claudia Vera Cumberbatch was born in, Trinidad, on 21 February 1915. When she was nine years old, her family emigrated to New York City following the post-war cocoa price crash in Trinidad. Her mother died five years later, and her father eventually found work to support the family. Jones won the Theodore Roosevelt Award for Good Citizenship at her junior high school. In 1932, due to poor living conditions, she was struck with tuberculosis, a condition that irreparably damaged her lungs and plagued her for the rest of her life. She graduated from high school, but her family could not afford the expenses to attend her graduation ceremony.[3]

United States career

Despite being academically bright, being classed as an immigrant woman severely limited Jones' career choices. Instead of going to college she began working in a laundry, and subsequently found other retail work in Harlem. During this time she joined a drama group, and began to write a column called "Claudia Comments" for a Harlem journal.[5]

In 1936, trying to find organisations supporting the Scottsboro Boys,[6][7] she joined the Young Communist League USA.[8] In 1937 she joined the editorial staff of the Daily Worker, rising by 1938 to become editor of the Weekly Review. After the Young Communist League became American Youth for Democracy during World War II, Jones became editor of its monthly journal, Spotlight. After the war, Jones became executive secretary of the Women's National Commission, secretary for the Women's Commission of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA), and in 1952 took the same position at the National Peace Council. In 1953, she took over the editorship of Negro Affairs.[9]

Black feminist leader in the Communist Party

As a member of the Communist Party USA and a black nationalist and feminist, Jones' focus was on creating "an anti-imperialist coalition, managed by working-class leadership, fuelled by the involvement of women."[10]

As the Communist Party had failed to generally acknowledge women's difficulty in securing work, Jones focused on growing the party's support for black and white women. She campaigned for job training programs, equal pay for equal work, government controls on food prices and funding for wartime childcare programs. Jones supported a subcommittee to address the "women's question". She insisted on the development in the party of theoretical training of women comrades, the organization of women into mass organizations, daytime classes for women, and "babysitter" funds to allow for women's activism.[10]

"An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman!"

Jones' best known piece of writing, "An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman!", appeared in 1949 in the magazine Political Affairs. It exhibits her development of what later came to be termed "intersectional" analysis within a Marxist framework.[11] In it, she wrote:

The bourgeoisie is fearful of the militancy of the Negro woman, and for good reason. The capitalists know, far better than many progressives seem to know, that once Negro women begin to take action, the militancy of the whole Negro people, and thus of the anti-imperialist coalition, is greatly enhanced.

Historically, the Negro woman has been the guardian, the protector, of the Negro family... As mother, as Negro, and as worker, the Negro woman fights against the wiping out of the Negro family, against the Jim Crow ghetto existence which destroys the health, morale, and very life of millions of her sisters, brothers, and children.

Viewed in this light, it is not accidental that the American bourgeoisie has intensified its oppression, not only of the Negro people in general, but of Negro women in particular. Nothing so exposes the drive to fascization in the nation as the callous attitude which the bourgeoisie displays and cultivates toward Negro women.[12]

Deportation

An elected member of the National Committee of the Communist Party USA, Jones also organised and spoke at events. As a result of her membership of CPUSA and various associated activities, in 1948 she was arrested and sentenced to the first of four spells in prison. Incarcerated on Ellis Island, she was threatened with deportation to Trinidad.

Following a hearing by the Immigration and Naturalization Service, she was found in violation of the McCarran Act for being an alien (non-US citizen) who had joined the Communist Party. Several witnesses testified to her role in party activities, and she had identified herself as a party member since 1936 when completing her Alien Registration on 24 December 1940, in conformity with the Alien Registration Act. She was ordered to be deported on 21 December 1950.[13]

In 1951, aged 36 and in prison, she suffered her first heart attack.[9] That same year, she was tried and convicted with 11 others, including her friend Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, of "un-American activities" under the Smith Act,[14] specifically activities against the United States government.[3] The Supreme Court refused to hear their appeal. In 1955, Jones began her sentence of a year and a day at the Federal Reformatory for Women at Alderson, West Virginia.[9] She was released on 23 October 1955.[15]

She was refused entry to Trinidad and Tobago, in part because the colonial governor Major General Sir Hubert Elvin Rance was of the opinion that "she may prove troublesome".[14] She was eventually offered residency in the United Kingdom on humanitarian grounds, and federal authorities agreed to allow it when she agreed to cease contesting her deportation.[16] On 7 December 1955, at Harlem's Hotel Theresa, 350 people met to see her off.[9]

United Kingdom activism

Jones arrived in London two weeks later, at a time when the British African-Caribbean community was expanding. However, on engaging the political community in the UK, she was disappointed to find that many British communists were hostile to a black woman.[17]

Activism

Jones found a community that needed active organisation.[14] She became involved in the British African-Caribbean community to organise both access to basic facilities, as well as the early movement for equal rights.[18]

Supported by her friends Trevor Carter, Nadia Cattouse, Amy Ashwood Garvey, Beryl McBurnie, Pearl Prescod and her lifelong mentor Paul Robeson, Jones campaigned against racism in housing, education and employment. She addressed peace rallies and the Trade Union Congress, and visited Japan, Russia, and China, where she met with Mao Zedong.[19]

In the early 1960s, her health failing, Jones helped organise campaigns against the Commonwealth Immigrants Bill (passed in April 1962), which would make it harder for non-whites to migrate to Britain. She also campaigned for the release of Nelson Mandela, and spoke out against racism in the workplace.[18]

West Indian Gazette and Afro-Asian Caribbean News, 1958

From her experiences in the United States, Jones believed that "people without a voice were as lambs to the slaughter."[19] In March 1958 above a barber's shop in Brixton,[14] she founded and thereafter edited the West Indian Gazette, its full title subsequently displayed on its masthead as West Indian Gazette and Afro-Asian Caribbean News (WIG).[20][21] The paper became a key contributor to the rise of consciousness within the Black British community.[19]

Jones wrote in her last published essay, "The Caribbean Community in Britain", in Freedomways (Summer 1964):[22]

The newspaper has served as a catalyst, quickening the awareness, socially and politically, of West Indians, Afro-Asians and their friends. Its editorial stand is for a united, independent West Indies, full economic, social and political equality and respect for human dignity for West Indians and Afro-Asians in Britain, and for peace and friendship between all Commonwealth and world peoples.

Always strapped for cash, WIG folded eight months and four editions after Jones's death in December 1964.[9]

Notting Hill riots and "Caribbean Carnival", 1959

In August 1958, four months after the launch of WIG, the Notting Hill race riots occurred, as well as similar disturbances in Robin Hood Chase, Nottingham.[23] In view of the racially driven analysis of these events by the existing daily newspapers, Jones began receiving visits from members of the black British community and also from various national leaders responding to the concern of their citizens, including Cheddi Jagan of British Guiana, Norman Manley of Jamaica, Eric Williams of Trinidad and Tobago, as well as Phyllis Shand Allfrey and Carl La Corbinière of the West Indies Federation.[9]

As a result, Claudia identified the need to "wash the taste of Notting Hill and Nottingham out of our mouths".[9] It was suggested that the British black community should have a carnival; it was December 1958, so the next question was: "In the winter?" Jones used her connections to gain use of St Pancras Town Hall in January 1959 for the first Mardi-Gras-based carnival,[24] directed by Edric Connor[25][26] (who in 1951 had arranged for the Trinidad All Steel Percussion Orchestra to appear at the Festival of Britain)[27] and with the Boscoe Holder Dance Troupe, jazz guitarist Fitzroy Coleman and singer Cleo Laine headlining;[25] the event was televised nationally by the BBC. These early celebrations were epitomised by the slogan: "A people's art is the genesis of their freedom."[23][28]

A footnote on the front cover of the original 1959 souvenir brochure states: "A part of the proceeds [from the sale] of this brochure are to assist the payments of fines of coloured and white youths involved in the Notting Hill events."[29] Jones and the West Indian Gazette also organised five other annual indoor Caribbean Carnival cabarets at such London venues as Seymour Hall, Porchester Hall and the Lyceum Ballroom, which events are seen as precursors of the celebration of Caribbean Carnival that culminated in the Notting Hill Carnival.[23]

Death

Jones died on Christmas Eve 1964, aged 49, and was found on Christmas Day at her flat. A post-mortem declared that she had suffered a massive heart attack, due to heart disease and tuberculosis.[14]

Her funeral on 9 January 1965 was a large and political ceremony, with her burial plot selected to be that located to the left of the tomb of her hero, Karl Marx, in Highgate Cemetery, North London.[30] A message from Paul Robeson was read out:[14]

It was a great privilege to have known Claudia Jones. She was a vigorous and courageous leader of the Communist Party of the United States, and was very active in the work for the unity of white and coloured peoples and for dignity and equality, especially for the Negro people and for women.

Legacy

The National Union of Journalists' Black Members' Council holds a prestigious annual Claudia Jones Memorial Lecture every October, during Black History Month, to honour Jones and celebrate her contribution to Black-British journalism.

The Claudia Jones Organisation was founded in London in 1982 by Yvette Thomas and others[31] to support and empower women and families of African-Caribbean heritage.[32][33]

Winsome Pinnock's 1989 play A Rock in Water was inspired by the life of Claudia Jones.[34][35]

Jones is named on the list of 100 Great Black Britons (2003 and 2020)[36] and in the 2020 book.[37]

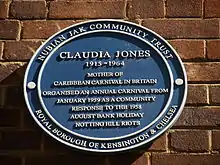

In August 2008, a blue plaque was unveiled on the corner of Tavistock Road and Portobello Road commemorating Claudia Jones as the "Mother of Caribbean Carnival in Britain".[38][39]

In October 2008, Britain's Royal Mail commemorated Jones with a special postage stamp.[40]

She is the subject of a documentary film by Z. Nia Reynolds, Looking for Claudia Jones (2010).[41]

On 14 October 2020, Jones was honoured with a Google Doodle.[42]

Commemoration of the 100th anniversary of her birth

Various activities took place from June 2014 onwards. The most successful were possibly those organised by Community Support, which put substantial resources into basic research into aspects of her life and work.

This led to new revelations and rediscoveries about Claudia Jones, not included in the three printed biographies, or the film biography.

Community Support organised A Claudia Jones 100 Day on the 100th anniversary of her birth at Kennington Park Estate Community Centre on Saturday, 21 February 2015. This began with a guided tour showing her two main residences while she lived in London, and the former West Indian Gazette office nearby.

There was also a celebration at The Cloth, in Belmont, Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, near to her birthplace, on the same day.[43]

The Day was associated with an event held on the previous evening at Claudia Jones Organisation in Hackney, which featured a screening of the film Looking for Claudia Jones by Z. Nia Reynolds.

References

- Taylor, Jeremy (May 2008). "Excavating Claudia". Caribbean Review of Books.

- Thomson, Ian (29 August 2009). "Here To Stay". The Guardian.

- Boyce Davies, Carole (2007). Left of Karl Marx: The Political Life of Black Communist Claudia Jones. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-4116-1.

- "African American Historic Property Survey" (PDF). City of Phoenix. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2014.

- Azikiwe, Abayomi (6 February 2013). "Claudia Jones defied racism, sexism and class oppression". Workers World.

- "Claudia Jones". The Rebel Researchers Collective. 23 December 2012. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014.

- "Claudia Jones, Communist". The Marxist-Leninist. 1 March 2010.

- Davis (visiting professor of Labour History at Royal Holloway, University of London), Mary (9 March 2015). "Claudia Jones: Communist, anti-racist and feminist". Morning Star. Archived from the original on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- Hinds, Donald (3 July 2008). "Claudia Jones and the 'West Indian Gazette'". Race & Class. doi:10.1177/03063968080500010602. S2CID 144401595. Archived from the original on 9 April 2010. Retrieved 29 October 2011 – via Institute of Race Relations.

- Lynn, Denise (Fall 2014). "Socialist Feminism and Triple Oppression". Journal for the Study of Radicalism. 8: 1–20. doi:10.14321/jstudradi.8.2.0001. S2CID 161970928.

- Mohammed, Sagal (25 July 2020). "Marxist, Feminist, Revolutionary: Remembering Notting Hill Carnival Founder Claudia Jones". Vogue. Condé Nast.

- Reprinted in Margaret Busby (ed.), Daughters of Africa: An International Anthology of Words and Writings by Women of African Descent (1992), Vintage pb edition, 1993, p. 262.

- "Ouster Ordered of Claudia Jones; Hearing Officer Finds Her an Alien Who Became Member of Communist Party Alien Registration Affidavit Additional Charge Sustained" (PDF). The New York Times. 22 December 1950. Retrieved 27 June 2012. (subscription required)

- Mahamdallie, Hassan (13 October 2004). "Claudia Jones". Socialist Worker. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- "Claudia Jones Loses; Communist Facing Ouster Is Denied Stay to Aid Charney" (PDF). The New York Times. 10 November 1955. Retrieved 27 June 2012. (subscription required)

- "Red Agrees to Leave Country" (PDF). The New York Times. 18 November 1955. Retrieved 27 June 2012. (subscription required)

- "Claudia Jones". Woman's Hour. BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- "Claudia Jones". Black History Month. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- Baku, Shango. "Claudia Jones Remembered". ITZ Caribbean. Archived from the original on 7 April 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- Schwarz, Bill (2003). "'Claudia Jones and the West Indian Gazette': Reflections on the Emergence of Post-colonial Britain". Twentieth Century British History. 14 (3): 264–285. doi:10.1093/tcbh/14.3.264. ISSN 0955-2359.

- "West Indian Gazette cover July 1962". Lambeth Landmark.

- Jones, Claudia, "The Caribbean Community in Britain", Freedomways V. 4 (Summer 1964), 341–57. Quoted in McClendon III, John H., "Jones, Claudia (1915–1964)", Blackpast.org.

- "Claudia Jones (1915–1964)". Black History Pages. Archived from the original on 3 January 2018.

- "City Air Makes One Free". The City Speaks | Staden Talar.

- Funk, Ray. "Notting Hill Carnival: Mas and the mother country". Caribbean Beat. No. 100.

- "History: 1959 – Elements of Caribbean Carnival". Notting Hill Carnival '14. Archived from the original on 11 July 2014.

- Notes, "(1954) Edric Connor & The Caribbeans – Songs from Jamaica", folkcatalogue.

- Ashi, Lauren. ""A people's art is the genesis of their freedom" – Claudia Jones". catchavibe.co.uk. Archived from the original on 26 January 2012. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- Blagrove Jr, Ishmahil (7 August 2014). "Notting Hill Carnival — the untold story". London Evening Standard.

- Edwards, Rhiannon (5 October 2012). "Claudia Jones celebrated at Highgate Cemetery". Ham & High. Archived from the original on 23 March 2014.

- Lewis, Lester. "Claudia Jones Organisation: Celebrating 21 Years of Service to the Black Community". Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- "Welcome to Claudia Jones Organisation".

- Margaret Busby; Nia Reynolds (5 March 2014). "Buzz Johnson obituary". The Guardian (online).

- Reid, Tricia (March 1989). "Claudia". West Indian Digest (161). pp. 29–30.

- Peacock, D. Keith (1999). "Chapter 9: So People Know We're Here: Black Theatre in Britain". Thatcher's Theatre: British Theatre and Drama in the Eighties. Greenwood Press. p. 179. ISBN 9780313299018. ISSN 0163-3821.

- "100 Great Black Britons – 100 Nominees". 100 Great Black Britons.

- "100 Great Black Britons – The Book". 100 Great Black Britons. 2020.

- "Claudia Jones Blue Plaque unveiled". ITZ Caribbean. 22 August 2008.

- "Claudia Jones". Open Plaques.

- "The Notting Hill Carnival on stamps", The British Postal Museum & Archive blog, 27 August 2010.

- "Looking for Claudia Jones trailer", Blackstock Films, 2010.

- "Celebrating Claudia Jones", Google, 14 October 2020.

- Dowlat, Rhondor (21 February 2015). "Claudia Jones' life remembered". Trinidad and Tobago Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015.

Sources

- Claudia Jones, "We Seek Full Equality for Women (1949)."

- Buzz Johnson, "I Think of My Mother": Notes on the Life and Times of Claudia Jones, London: Karia Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0946918027.

- Marika Sherwood, Claudia Jones: A Life in Exile: A Biography, Lawrence & Wishart, 1999. ISBN 978-0853158820.

- "Claudia Jones", Special issue: BASA Newsletter #44, January 2006

- Carole Boyce Davies, Left of Karl Marx: The Political Life of Black Communist Claudia Jones, Duke University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0822341161.

- Carole Boyce Davies, Claudia Jones: Beyond Containment, Ayebia Clarke Publishing, 2011. ISBN 978-0956240163.

Further reading

- Clarke, Camryn S. (2017). Escaping the Master's House: Claudia Jones & The Black Marxist Feminist Tradition (Thesis). Hartford, Connecticut: Senior Theses, Trinity College – via Senior Theses and Projects, Trinity College Digital Repository.

- Gore, Dayo. Radicalism at the Crossroads: African American Women Activists in the Cold War. NYU Press, 2011.

- de Haan, Francisca (2013). "Eugénie Cotton, Pak Chong-ae, and Claudia Jones: Rethinking Transnational Feminism and International Politics". Journal of Women's History. 25 (4): 174–189. doi:10.1353/jowh.2013.0055. ISSN 1527-2036.

- Guy-Sheftall, Beverly, Words of Fire: an Anthology of African-American Feminist Thought. The New Press, 1995.

- Howard, Walter T. We Shall Be Free!: Black Communist Protests in Seven Voices. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2013.

- Marable, Manning, & Leith Mullings, Let Nobody Turn Us Around: Voices of Resistance, Reform, and Renewal. Rowman & Littlefield, 2009.

- Washington, Mary Helen, "Alice Childress, Lorraine Hansberry and Claudia Jones: Black Women Write the Popular Front", in Bill V. Mullin and James Smethurst (eds), Left of the Color Line: Race, Radicalism and 20th Century United States Literature. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Claudia Jones |

- List of 100 great black Britons

- "Claudia Jones", Exploring 20th Century London.

- "Mother of the Mas", biodata for Claudia Cumberbatch Jones, Fox Carnival Band.

- Ian Thomson, "Here To Stay", article on Donald Hinds, referencing Claudia Jones.

- "Claudia Jones The Black Woman that created London Carnival". YouTube video.

- Anna Clarke, "Remembering Claudia Jones, pioneer of the Notting Hill Carnival", The Daily Telegraph, 26 September 2018.