Cleveland Elementary School shooting (Stockton)

The Cleveland Elementary School shooting (also known as the Stockton schoolyard shooting and the Cleveland School massacre) occurred on January 17, 1989, at Cleveland Elementary School at 20 East Fulton Street in Stockton, California, United States. The gunman, Patrick Purdy, who had an extended criminal history, shot and killed five schoolchildren and wounded 32 others. As first responders arrived at the scene, Purdy committed suicide by shooting himself in the head. His victims were predominantly Southeast Asian refugees. This particular shooting happened almost exactly ten years after another school shooting in San Diego, which happened to be at a school named Grover Cleveland Elementary.

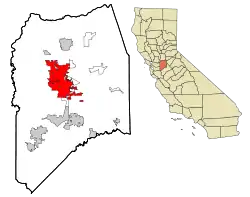

| Stockton schoolyard shooting | |

|---|---|

Location of Stockton city. | |

| Location | Stockton, California, US |

| Coordinates | 37°58′56″N 121°18′03″W |

| Date | January 17, 1989 11:59 am – 12:02 pm (PST) |

| Target | Students and faculty at Cleveland Elementary School |

Attack type | School shooting, mass murder, murder-suicide, massacre, domestic terrorism, suicide attack, arson, hate crime |

| Weapons | |

| Deaths | 6 (including the perpetrator) |

| Injured | 32[1] |

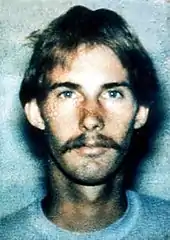

| Perpetrator | Patrick Purdy |

| Motive | Unknown, but likely racial hatred, eviction, personal and legal stress. |

The attack was the U.S. non-college school shooting with the highest number of fatalities and injuries until the Columbine High School massacre. Of all U.S. school shootings in the 1980s, it had the largest number of victims.

Shooting

| Victim fatalities |

|---|

|

Tuesday morning January 17, 1989, an anonymous person phoned the Stockton Police Department regarding a death threat against Cleveland Elementary School in Stockton, California. At noon that day, Patrick Purdy, a disturbed drifter and former Stockton resident, began his attack by setting his fireworks-laden Chevrolet station wagon[2] on fire with a Molotov cocktail after parking it behind the school, later causing the vehicle to explode. Purdy went to the school playground, where he began firing with a semi-automatic rifle from behind a portable building. Purdy fired 106 rounds in three minutes, killing five children and wounding thirty others, including one teacher.[3]

All of those who died and many of the wounded were Cambodian and Vietnamese immigrants, who had come with their families to the U.S. as refugees.[4] Purdy committed suicide by shooting himself in the head with a pistol.[5] He had carved the words "freedom", "victory", "Earthman", and "Hezbollah" on his rifle, and his flak jacket was inscribed with "PLO", "Libya", and "death to the Great Satin" [sic].

Perpetrator

Patrick Edward Purdy (November 10, 1964 – January 17, 1989) was an unemployed former welder and drifter. He was born in Tacoma, Washington, to Patrick Benjamin Purdy and Kathleen Toscano. His father was a soldier in the U.S. Army and was stationed at Fort Lewis at the time of his son's birth. When the younger Purdy was two years old, his mother filed for divorce against her husband after he had threatened to kill her with a firearm. Toscano later moved with her son to South Lake Tahoe[6] before settling in Stockton, California.[7] Purdy attended Cleveland Elementary from kindergarten through second grade.[7][8]

Purdy's mother remarried in September 1969; she divorced her husband four years later. Albert Gulart, Sr., Purdy's stepfather, said Purdy was an overly quiet child who cried often. In fall 1973, Kathleen separated from Gulart and moved with her children from Stockton to the Sacramento area. In December of that year, the Sacramento Child Protective Services were twice called to her residence, on allegations that Kathleen was physically abusing her children.[9] When Purdy was thirteen, he struck his mother in the face and was permanently banned from her house.[10] He lived on the streets of San Francisco for a period before being placed in foster care by authorities.[9] He was later placed in the custody of his father, who was living in Lodi, California, at the time.[10] While attending Lodi High School, Purdy became an alcoholic and a drug addict, and attended high school sporadically.[3][7]

On September 13, 1981, Purdy's father was killed after being struck by a car.[10] His family filed a wrongful-death suit in San Joaquin Superior Court against the driver of the car, asking for US$600,000 in damages; the suit was later dismissed. Purdy accused his mother of taking money his father had left him, using the money to buy a car and taking a vacation to New York City. This incident appeared to deepen the animosity between them.[11][12] After his father's death, Purdy was briefly homeless, before being placed in the custody of a foster mother in Los Angeles.[9]

Purdy’s criminal activities had begun by 1977, when Sacramento police confiscated BB guns from then 12-year-old Purdy.[9] In June 1980, Purdy was first arrested at age 15 for a court-order violation.[10] He was arrested that same month for underage drinking. Purdy was then arrested for prostitution in August 1980,[13][14] possession of marijuana and drug dealing in 1982, and in 1983 for possession of an illegal weapon and receipt of stolen property. On October 11, 1984, he was arrested for being an accomplice in an armed robbery at a service station, for which he spent 32 days in the Yolo County Jail. In 1986, Kathleen called police after Purdy vandalized her car after she refused to give him money for narcotics.[7][15]

In April 1987, Purdy and his half-brother Albert were arrested for firing a semi-automatic pistol at trees in the Eldorado National Forest. At the time, he was carrying a book about the white supremacist group Aryan Nations. He told the County Sheriff that it was his "duty to help the suppressed and overthrow the suppressor."[16] In prison, he twice attempted suicide, once by hanging himself with a rope made out of strips of his shirt, and a second time by cutting his wrists with his fingernails. A subsequent psychiatric assessment found him to suffer from very mild mental retardation, and to be a danger to himself and others.[16][17]

In the fall of 1987, Purdy began attending welding classes at San Joaquin Delta College; he complained about the high percentage of Southeast Asian students there. In October 1987, he left California and drifted among Oregon, Nevada, Texas, Florida, Connecticut, South Carolina, and Tennessee, searching for jobs. In early 1988, he worked at Numeri Tech, a small machine shop located in Stockton. From July to October 1988, he worked as a boilermaker in Portland, Oregon, living in Sandy with his aunt.

On August 3 in Sandy, he purchased a Chinese-made AK-47 at Sandy Trading Post,[18] which he later used in the shooting. He eventually returned to Stockton and rented a room at the El Rancho Motel on December 26. After the shooting, police found his room decorated with numerous toy soldiers.[3][7][11] On December 28, Purdy purchased a Taurus pistol at Hunter Loan and Jewelry Company in Stockton.

Police stated that Purdy had problems with alcohol and drug addiction. He was said to have been a misanthrope, directing hatred toward Asian immigrants,[16] believing that they took jobs from "native-born" Americans.[12][19] According to Purdy's friends, who described him as friendly and never violent toward anyone, he was suicidal at times and frustrated that he failed to "make it on his own".[16] Steve Sloan, a night-shift supervisor at Numeri Tech, said: "He was a real ball of frustration, and was angry about everything." Another one of Purdy's former co-workers stated, "He was always miserable. I've never seen a guy that didn't want to smile as much as he didn't."[16] In a notebook found in a hotel where he lived in early 1988, Purdy wrote about himself in the following terms: "I'm so dumb, I'm dumber than a sixth-grader. My mother and father were dumb."[7]

Reaction and aftermath

The multiple murders at Stockton received national news coverage and spurred calls for regulation of semiautomatic weapons. "Why could Purdy, an alcoholic who had been arrested for such offenses as selling weapons and attempted robbery, walk into a gun shop in Sandy, Oregon, and leave with an AK-47 under his arm?", Time magazine asked. The article continued: "The easy availability of weapons like this, which have no purpose other than killing human beings, can all too readily turn the delusions of sick gunmen into tragic nightmares."[5] A few weeks after the shooting, singer Michael Jackson made a short visit to the school and met with some of the children affected by the event.[20]

In California, measures were taken to first define and then ban assault weapons, resulting in the Roberti-Roos Assault Weapons Control Act of 1989. On the federal level, Congressional legislators struggled with a way to ban weapons such as military-style rifles without banning sporting-type rifles. In 1989, the ATF issued a rule citing the lack of "sporting purpose" to ban importation of assault weapons. In July 1989, the G.H.W. Bush Administration made the import ban permanent.[21] The Federal Assault Weapons Ban was enacted in 1994, and expired in 2004. President Bill Clinton signed another executive order in 1994 which banned importation of most firearms and ammunition from China.[22]

References

- "About: Cleveland School Remembers".

- Times, Robert Reinhold and Special To the New York. "After Shooting, Horror but Few Answers".

- Schoolyard gunman called a troubled drifter, The Deseret News (January 18, 1989)

- Jay Mathews, Matt Lait, "Rifleman slays five at school", Washington Post, Jan, 18, 1989, pg. A1.

- Slaughter in A School Yard, Time magazine, (January 30, 1989)

- INGRAM, CARL; JONES, ROBERT A. (January 19, 1989). "Gunman Had Attended School He Assaulted: But Motive Remains Unclear in Attack" – via LA Times.

- From quiet, unhappy child to mass killer, San Jose Mercury News (January 19, 1989)

- Gunman Had Attended School He Assaulted But Motive Remains Unclear in Attack, Los Angeles Times (January 19, 1989)

- Phillips, Roger. "Purdy recalled as bigot and 'sick, sick man'".

- Under Fire, Osha Gray Davidson

- "Troubled drifter erupted, became killer", The Deseret News, (January 22, 1989)

- " 'Man who never smiled' resented the Vietnamese", San Jose Mercury News (January 19, 1989)

- "Search.com". Metasearch Search Engine. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- Archived October 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Toy soldiers, Middle-East fantasies", Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (January 19, 1989)

- Gunman "hated Vietnamese", The Prescott Courier (January 19, 1989)

- https://www.deseretnews.com/article/31555/TROUBLED-DRIFTER-ERUPTED-BECAME-KILLER.html

- Weapon Used by Deranged Man Is Easy to Buy", The New York Times, January 19, 1989

- "Warped killers share mental problems", The Prescott Courier (January 20, 1989)

- "Rocker visits Stockton school", Santa Cruz Sentinel (February 8, 1989), p. 8.

- Rasky, Susan F. "Import Ban on Assault Rifles Becomes Permanent". Retrieved May 9, 2018.

- "National Institute of Justice Brief — PDF file" (PDF).

Further reading

- Vanairsdale, S. T. (January 2014). "Trigger Effect". Sactown. Retrieved June 21, 2014.

- 25th Anniversary of Cleveland Elementary Shooting, The Huffington Post (January 16, 2014)

- 20 years later: Remembering the Tragedy, The Stockton Record (January 18, 2009)

- Five Children Killed As Gunman Attacks A California School, The New York Times (January 18, 1989)

- After Shooting, Horror but Few Answers, The New York Times (January 19, 1989)

- Killer Depicted as Loner Full of Hate The New York Times (January 20, 1989)

- Effort to Ban Assault Rifles Gains Momentum, The New York Times (January 28, 1989)

- Ban on Assault Rifles Takes Effect in Los Angeles, The New York Times (March 3, 1989)

- Stockton Journal; Where 5 Died, a Monk Gives Solace, The New York Times (May 11, 1989)

- Title 18 USC Chapter 44 — PDF file

- Title 26 USC Chapter 53 — PDF file